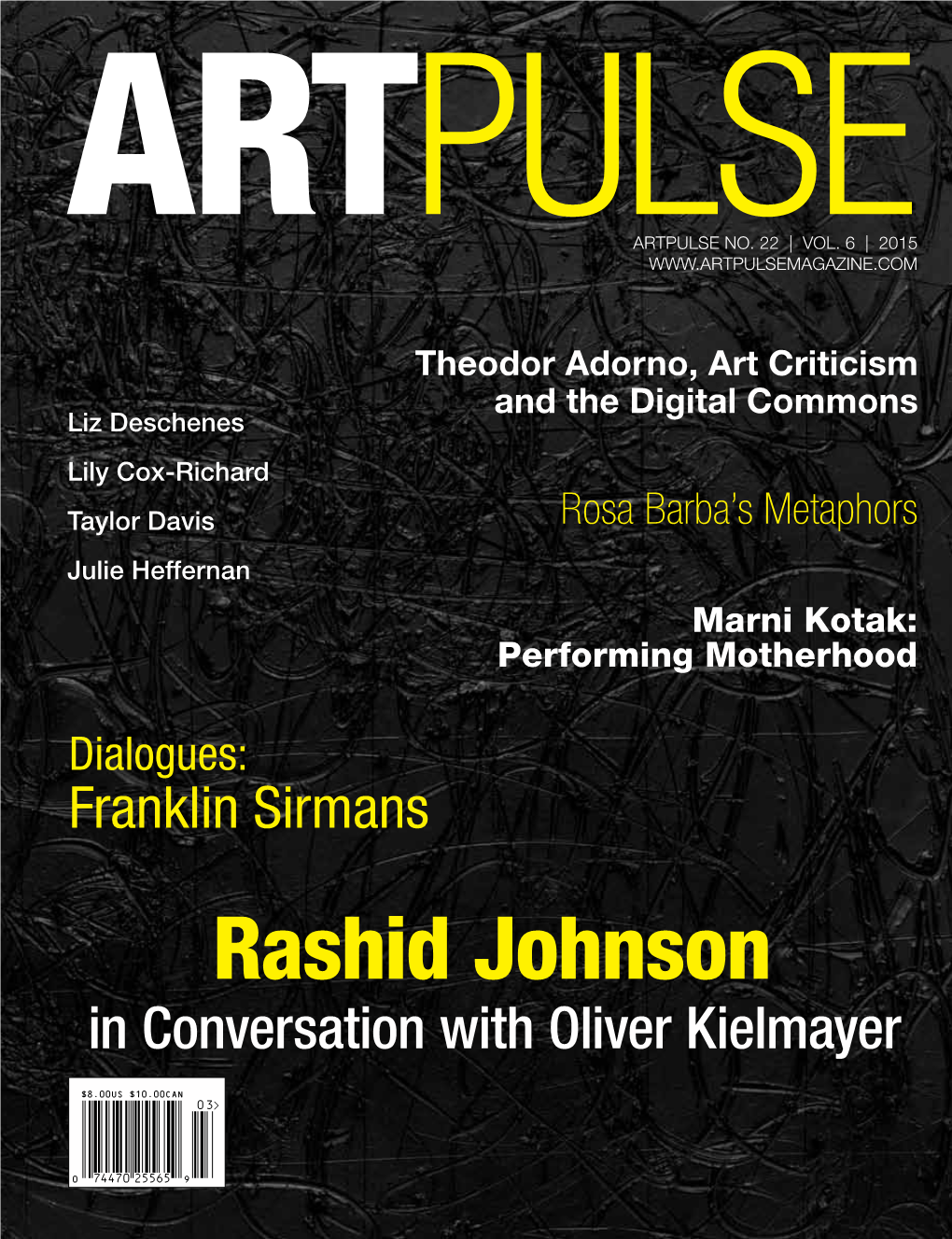

Rashid Johnson in Conversation with Oliver Kielmayer

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

THE WASHINGTON COLOR SCHOOL on View September 9, 2021 – October 23, 2021

For Immediate Release EDWARD TYLER NAHEM PRESENTS PRIMACY: THE WASHINGTON COLOR SCHOOL On View September 9, 2021 – October 23, 2021 Opening Reception: Thursday September 9, 2021 (6:00pm– 8:00pm) (New York) – August 23, 2021 – Edward Tyler Nahem Fine Art (ETNFA) is pleased to present Primacy: The Washington Color School, an exhibition curated by Dexter Wimberly of paintings by nine eminent Washington Color School artists: Cynthia Bickley-Green, Gene Davis, Sam Francis, Sam Gilliam, Morris Louis, Howard Mehring, Kenneth Noland, Alma Thomas, and Kenneth V. Young. The origin of the Washington Color School is linked to a 1965 exhibition titled The Washington Color Painters, organized by Gerald Norland at the Washington Gallery of Modern Art in Washington D.C. Five of the six artists in the original 1965 Washington Color Painters exhibition are included in Primacy. Artists of the Washington Color School are distinguished by their rejection of gesture in favor of flat, hard-edged planes of color, as seen in Gene Davis’s adroitly executed Red Dog (ca. 1961) and Morris Louis’s Number 19 (1962), two works in the exhibition that create optical effects and showcase the transcendent potential of painting. Hung next to Howard Mehring’s Blue Note (1964) and Kenneth Noland’s Untitled (1965), these deceptively simple compositions radiate dynamism and tension. In the vanguard of experimentation, the Washington Color School artists pushed boundaries with techniques and processes that would lead them to form individual but related styles, all of which emerged in reaction to Abstract Expressionism. This point of origin is clearly seen in the earliest work in the exhibition, Study for Moby Dick (1958) by Sam Francis, an artist associated with both the Abstract Expressionist movement and Post-Painterly Abstraction. -

Zombies in Western Culture: a Twenty-First Century Crisis

JOHN VERVAEKE, CHRISTOPHER MASTROPIETRO AND FILIP MISCEVIC Zombies in Western Culture A Twenty-First Century Crisis To access digital resources including: blog posts videos online appendices and to purchase copies of this book in: hardback paperback ebook editions Go to: https://www.openbookpublishers.com/product/602 Open Book Publishers is a non-profit independent initiative. We rely on sales and donations to continue publishing high-quality academic works. Zombies in Western Culture A Twenty-First Century Crisis John Vervaeke, Christopher Mastropietro, and Filip Miscevic https://www.openbookpublishers.com © 2017 John Vervaeke, Christopher Mastropietro and Filip Miscevic. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license (CC BY 4.0). This license allows you to share, copy, distribute and transmit the work; to adapt the work and to make commercial use of the work providing attribution is made to the authors (but not in any way that suggests that they endorse you or your use of the work). Attribution should include the following information: John Vervaeke, Christopher Mastropietro and Filip Miscevic, Zombies in Western Culture: A Twenty-First Century Crisis. Cambridge, UK: Open Book Publishers, 2017, http://dx.doi. org/10.11647/OBP.0113 In order to access detailed and updated information on the license, please visit https:// www.openbookpublishers.com/product/602#copyright Further details about CC BY licenses are available at http://creativecommons.org/licenses/ by/4.0/ All external links were active at the time of publication unless otherwise stated and have been archived via the Internet Archive Wayback Machine at https://archive.org/web Digital material and resources associated with this volume are available at https://www. -

Neural Systems of Visual Attention Responding to Emotional Gestures

Neural systems of visual attention responding to emotional gestures Tobias Flaisch a,⁎, Harald T. Schupp a, Britta Renner a, Markus Junghöfer b a Department of Psychology, University of Konstanz, P.O. Box D 36, 78457 Konstanz, Germany b Institute for Biomagnetism and Biosignalanalysis, Münster University Hospital, Malmedyweg 1, 48149 Münster, Germany abstract Humans are the only species known to use symbolic gestures for communication. This affords a unique medium for nonverbal emotional communication with a distinct theoretical status compared to facial expressions and other biologically evolved nonverbal emotion signals. While a frown is a frown all around the world, the relation of emotional gestures to their referents is arbitrary and varies from culture to culture. The present studies examined whether such culturally based emotion displays guide visual attention processes. In two experiments, participants passively viewed symbolic hand gestures with positive, negative and neutral emotional meaning. In Experiment 1, functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) measurements showed that gestures of insult and approval enhance activity in selected bilateral visual associative brain regions devoted to object perception. In Experiment 2, dense sensor event related brain potential recordings (ERP) revealed that emotional hand gestures are differentially processed already 150 ms poststimulus. Thus, the present studies provide converging neuroscientific evidence that emotional gestures provoke the cardinal signatures of selective visual attention regarding brain structures and temporal dynamics previously shown for emotional face and body expressions. It is concluded that emotionally charged gestures are efficient in shaping selective attention processes already at the level of stimulus perception. Introduction their referents is arbitrary, builds upon shared meaning and convention, and consequently varies from culture to culture (Archer, In natural environments, emotional cues guide visual attention 1997). -

Patricia Hills Professor Emerita, American and African American Art Department of History of Art & Architecture, Boston University [email protected]

1 Patricia Hills Professor Emerita, American and African American Art Department of History of Art & Architecture, Boston University [email protected] Education Feb. 1973 PhD., Institute of Fine Arts, New York University. Thesis: "The Genre Painting of Eastman Johnson: The Sources and Development of His Style and Themes," (Published by Garland, 1977). Adviser: Professor Robert Goldwater. Jan. 1968 M.A., Hunter College, City University of New York. Thesis: "The Portraits of Thomas Eakins: The Elements of Interpretation." Adviser: Professor Leo Steinberg. June 1957 B.A., Stanford University. Major: Modern European Literature Professional Positions 9/1978 – 7/2014 Department of History of Art & Architecture, Boston University: Acting Chair, Spring 2009; Spring 2012. Chair, 1995-97; Professor 1988-2014; Associate Professor, 1978-88 [retired 2014] Other assignments: Adviser to Graduate Students, Boston University Art Gallery, 2010-2011; Director of Graduate Studies, 1993-94; Director, BU Art Gallery, 1980-89; Director, Museum Studies Program, 1980-91 Affiliated Faculty Member: American and New England Studies Program; African American Studies Program April-July 2013 Terra Foundation Visiting Professor, J. F. Kennedy Institute for North American Studies, Freie Universität, Berlin 9/74 - 7/87 Adjunct Curator, 18th- & 19th-C Art, Whitney Museum of Am. Art, NY 6/81 C. V. Whitney Lectureship, Summer Institute of Western American Studies, Buffalo Bill Historical Center, Cody, Wyoming 9/74 - 8/78 Asso. Prof., Fine Arts/Performing Arts, York College, City University of New York, Queens, and PhD Program in Art History, Graduate Center. 1-6/75 Adjunct Asso. Prof. Grad. School of Arts & Science, Columbia Univ. 1/72-9/74 Asso. -

One of a Kind, Unique Artist's Books Heide

ONE OF A KIND ONE OF A KIND Unique Artist’s Books curated by Heide Hatry Pierre Menard Gallery Cambridge, MA 2011 ConTenTS © 2011, Pierre Menard Gallery Foreword 10 Arrow Street, Cambridge, MA 02138 by John Wronoski 6 Paul* M. Kaestner 74 617 868 20033 / www.pierremenardgallery.com Kahn & Selesnick 78 Editing: Heide Hatry Curator’s Statement Ulrich Klieber 66 Design: Heide Hatry, Joanna Seitz by Heide Hatry 7 Bill Knott 82 All images © the artist Bodo Korsig 84 Foreword © 2011 John Wronoski The Artist’s Book: Rich Kostelanetz 88 Curator’s Statement © 2011 Heide Hatry A Matter of Self-Reflection Christina Kruse 90 The Artist’s Book: A Matter of Self-Reflection © 2011 Thyrza Nichols Goodeve by Thyrza Nichols Goodeve 8 Andrea Lange 92 All rights reserved Nick Lawrence 94 No part of this catalogue Jean-Jacques Lebel 96 may be reproduced in any form Roberta Allen 18 Gregg LeFevre 98 by electronic or mechanical means, including photocopying, recording, or information storage retrieval Tatjana Bergelt 20 Annette Lemieux 100 without permission in writing from the publisher Elena Berriolo 24 Stephen Lipman 102 Star Black 26 Larry Miller 104 Christine Bofinger 28 Kate Millett 108 Curator’s Acknowledgements Dianne Bowen 30 Roberta Paul 110 My deepest gratitude belongs to Pierre Menard Gallery, the most generous gallery I’ve ever worked with Ian Boyden 32 Jim Peters 112 Dove Bradshaw 36 Raquel Rabinovich 116 I want to acknowledge the writers who have contributed text for the artist’s books Eli Brown 38 Aviva Rahmani 118 Jorge Accame, Walter Abish, Samuel Beckett, Paul Celan, Max Frisch, Sam Hamill, Friedrich Hoelderin, John Keats, Robert Kelly Inge Bruggeman 40 Osmo Rauhala 120 Andreas Koziol, Stéphane Mallarmé, Herbert Niemann, Johann P. -

Helix: Algorithm/Architecture Co-Design for Accelerating Nanopore Genome Base-Calling

Helix: Algorithm/Architecture Co-design for Accelerating Nanopore Genome Base-calling Qian Lou Sarath Janga Lei Jiang [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] Indiana University Bloomington Indiana University - Purdue Indiana University Bloomington University Indianapolis ABSTRACT KEYWORDS Nanopore genome sequencing is the key to enabling personalized nanopore sequencing; base-calling; processing-in-memory medicine, global food security, and virus surveillance. The state-of- ACM Reference Format: the-art base-callers adopt deep neural networks (DNNs) to trans- Qian Lou, Sarath Janga, and Lei Jiang. 2020. Helix: Algorithm/Architecture late electrical signals generated by nanopore sequencers to digital Co-design for Accelerating Nanopore Genome Base-calling. In Proceedings DNA symbols. A DNN-based base-caller consumes 44:5% of to- of the 2020 International Conference on Parallel Architectures and Compilation tal execution time of a nanopore sequencing pipeline. However, Techniques (PACT ’20), October 3–7, 2020, Virtual Event, GA, USA. ACM, New it is difficult to quantize a base-caller and build a power-efficient York, NY, USA, 12 pages. https://doi.org/10.1145/3410463.3414626 processing-in-memory (PIM) to run the quantized base-caller. Al- though conventional network quantization techniques reduce the 1 INTRODUCTION computing overhead of a base-caller by replacing floating-point Genome sequencing [8, 21, 34, 35, 37] is a cornerstone for enabling multiply-accumulations by cheaper fixed-point operations, it sig- personalized medicine, global food security, and virus surveillance. nificantly increases the number of systematic errors that cannot The emerging nanopore genome sequencing technology [15] is be corrected by read votes. The power density of prior nonvolatile revolutionizing the genome research, industry and market due to memory (NVM)-based PIMs has already exceeded memory thermal its ability to generate ultra-long DNA fragments, aka long reads, tolerance even with active heat sinks, because their power efficiency as well as provide portability. -

2019-2020 Year in Review

YEAR in REVIEW July 1, 2019– June 30, 2020 BOWDOIN COLLEGE MUSEUM OF ART BRUNSWICK, MAINE C FROM THE CO-DIRECTORS The Bowdoin College Museum of Art serves as an invaluable educational resource for the campus and beyond. It is a champion of the visual arts, a place for reflection and dialogue, and an engine for the production and diffusion of knowledge. During the past academic year, the Museum dedicated itself to reaching out to and engaging with students, faculty and staff, and the wider community. On March 16, 2020, the Walker Art Building—home of the Museum of Art—closed to the public as a precaution against COVID-19. Yet, the Museum has continued to embrace its mission. We are proud of the work done by our colleagues to support remote teaching and learning on the part of faculty and students and by the commitment to create educational resources for the public. The Museum’s new landing page features many of our new digital assets, including online exhibitions, program recordings, publications, and our new “Visit from Home” portal. The past year has brought greater public attention to the long-standing problem of systemic racism in the United States. We feel it is imperative to renew our commitment to inclusivity and equity. Towards this end, the Museum has organized an Anti-Racism Task Force and has inaugurated an Anti-Racism Action Plan, which will guide further outreach and change. Through these twin pandemics, we recognize more than ever that artists are essential workers. We miss seeing their work in person, though appreciate that the arts have much to offer in fostering dialogue and building community. -

At Mass Moca, Reimagining Photography

PHOTOGRAPHY REVIEW At Mass MoCA, reimagining photography CLIFFORD ROSS) Clifford Ross’ “Mountain IV” By Mark Feeney GLOBE STAFF JUNE 18, 2015 NORTH ADAMS — Familiarity may or may not breed contempt. It can certainly breed lack of imagination. Photography has never been more ubiquitous. A chicken in every pot never happened — thanks to cellphones, a digital camera in every pocket or purse pretty much has. Why would anyone, including artists, feel a need to rethink anything so common and useful? Yet that very ubiquity makes fresh responses to the medium all the more useful, and fresh responses are what three shows at the Massachusetts Museum of Contemporary Art offer. “Clifford Ross: Landscape Seen & Imagined” reminds us that photography involves seeing by two parties: the photographer, and the viewer of the photographs taken. There’s nothing remarkable about this fact, except that Ross makes it so through his use of scale. Much of the show runs through March. Another portion, the “Hurricane Wave” series, runs through Aug. 30. In addition, an “immersive outdoor video installation,” as Mass MoCA describes it, will be on display most Thursday and Friday evenings between June 26 and Sept. 4. Ross’ “Hurricane L” That video display isn’t the only thing immersive about Ross’s work. Simply described, “Sopris Wall I” is a photograph of Mount Sopris, in the Colorado Rockies, flanked by trees, with a small body of water in the foreground. That description, while accurate enough so far as it goes, goes nowhere near far enough to give any sense of the experience of seeing “Sopris Wall I” in person. -

Improving Communication Based on Cultural

IMPROVING COMMUNICATION BASED ON CULTURAL COMPETENCY IN THE BUSINESS ENVIRONMENT by Walter N. Burton III A Dissertation Submitted to the Faculty of The Dorothy F. Schmidt College of Arts and Letters in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Florida Atlantic University Boca Raton, Florida May 2011 IMPROVING COMMUNICATION BASED ON CULTURAL COMPETENCY IN THE BUSINESS ENVIRONMENT by Walter N. Burton III This dissertation was prepared under the direction of the candidate's dissertation advisor, Dr. Patricia Darlington, School of Communication and Multimedia Studies, and has been approved by the members ofhis supervisory committee. It was submitted to the faculty of The Dorothy F. Schmidt College of Arts and Letters and was accepted in partial fulfillment ofthe requirements for the degree ofDoctor ofPhilosophy. SUPERVISORY COMMITTEE: ~o--b Patricia Darlington, Ph.D. ~.:J~~ Nannetta Durnell-Uwechue, Ph.D. ~~C-~ Arthur S. E ans, J. Ph.D. c~~~Q,IL---_ Emily~ard, Ph.D. Director, Comparative Studies Program ~~~ M~,Ph.D. Dean, The Dorothy F. Schmidt College ofArts & Letters ~~~~ Dean, Graduate College ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to thank the members of my committee Prof. Patricia Darlington, Prof. Nennetta Durnell-Uwechue, Prof. Arthur Evans, and Prof. Angela Rhone for your diligent readings of my work as well as your limitless dedication to the art of teaching. I would like to offer a special thanks to my Chair Prof. Patricia Darlington for your counsel in guiding me through this extensive and arduous project. I speak for countless students when I say that over the past eight years your inspiration, guidance, patience, and encouragement has been a constant beacon guiding my way through many perils and tribulations, along with countless achievements and accomplishments. -

Irish Artist Featured at World's Most Prestigious Art Biennale

Press Release 19th April 2013 Irish artist featured at world’s most prestigious Art Biennale Minister Jimmy Deenihan, TD, announces Ireland’s Representation for the 55th International Art Exhibition at Dublin Launch in RHA The Minister for Arts, Heritage and the Gaeltacht, Jimmy Deenihan TD, will today (19 April 2013), be joined by artists, curators and invited guests at the Dublin launch of Ireland's representation at the 55th International Art Exhibition in Venice. Ireland at Venice is an initiative of the Department of Arts, Heritage and the Gaeltacht's Culture Ireland division in partnership with the Arts Council, the Irish Government agency for funding and developing the arts. Richard Mosse has been selected as the artist to represent Ireland at the Venice Art Biennale and Anna O’Sullivan, Director of the Butler Gallery is the Commissioner. The Venice Biennale has for a century held its place as the most important international showcase for visual arts and in recent years has attracted 400,000 visitors. Speaking at the launch in the Royal Hibernian Academy, Minister Jimmy Deenihan TD., said "the Biennale represents an immense opportunity for Irish artists to present their work at the leading visual arts showcase in the world and to gain international exposure to high profile curators and collectors.’ He went on to say that this showcase is not only a focus on Richard but is also an opportunity to attract attention to the depth, strength and diversity of a generation of visual artists working in Ireland. "I am confident that Richard’s work will be highly regarded alongside that of the other international artists in Venice’ added the Minister. -

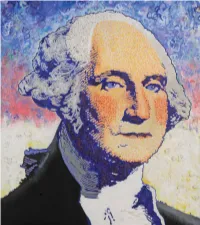

Michael Clark (A.K.A

ARTIST MICHAEL CLARK: WASHINGTON April 3 – May 27, 2018 American University Museum at the Katzen Arts Center Washington, DC ALPER INITIATIVE FOR WASHINGTON ART FOREWORD Michael Clark (a.k.a. Clark Fox) has been an influential figure in the Washington art world for more than 50 years, despite dividing his time equally between the capital and New York City. Clark was not only a fly on the wall of the art world as the last half- century played out—he was in the middle of the action, making innovative works that draw their inspiration from movements as diverse as Pop Art, Op Art, Conceptual Art, Minimalism, and the Washington Color School. The result of this prolific and varied artistic oeuvre is that Clark’s output is too much for one show. After consulting with former Washington Post art critic Paul Richard, I decided Michael Clark: Washington Artist at the American University Museum would concentrate on his significant artistic contributions to the ‘60s, ‘70s, and ‘80s in Washington, DC. In line with his amazingly diverse and productive career, a conversation with Michael Clark is similar to drinking from a fire hose. In one sentence, he can jump from painting techniques using masking tape to making cookies for Jackie Onassis. My transcription of our conversation, presented here as a soliloquy, tries its best to maintain some kind of coherence and order, but in reality, I just tried to hold on for the ride. In contrast, the amazing thing about Clark’s art is how still, focused, and composed it is. The leaps and diversions of his lively mind are transmuted into an almost classical art, more Modigliani than Soutine, probably reflecting the time spent in his early years copying masterworks in the National Gallery of Art. -

Sackboy Planet: Connected Learning Among Littlebigplanet 2 Players

WELCOME TO SACKBOY PLANet: Connected Learning Among LittleBigPlanet 2 Players by Matthew H. Rafalow Katie Salen Tekinbaş CONNECTED LEARNING WORKING PAPERS April 8, 2014 Digital Media and Learning Research Hub This digital edition of Welcome to Sackboy Planet: Connected Learning Among LittleBigPlanet 2 Players is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution Unported 3.0 License (CC BY 3.0) http://creativecommons.org/ licenses/by/3.0/ Published by the Digital Media and Learning Research Hub. Irvine, CA. March 2014. A full-text PDF of this report is available as a free download from www.dmlhub.net/publications Suggested citation: Rafalow, Matthew H., and Katie Salen Tekinbaş. 2014. Welcome to Sackboy Planet: Connected Learning Among LittleBigPlanet 2. Irvine, CA: Digital Media and Learning Research Hub. This report series on connected learning was made possible by grants from the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation in connection with its grant making initiative on Digital Media and Learning. For more information on the initiative visit www.macfound.org. For more information on connected learning visit www.connectedlearning.tv. 2 | WELCOME TO SACKBOY PLANET CONTENTS 5 INTRODUCTION 9 DESCRIPTION OF RESEARCH STUDY 10 Background: LittleBigPlanet 2 13 Youth StorY: Chris (AKA, GAdget42) 14 ANALYSIS: CONNECTED LEARNING AMONG LITTLEBIGPLANET 2 PLAYERS 15 Interest-Powered 16 Peer-Supported 19 Academically Oriented 22 Production-Centered 25 Openly Networked 29 Shared Purpose 32 DEVeloper StorY: AleX 33 REFLECTIONS 33 Barriers Tied to Gender 35 Gamification and Reputation Systems 37 Attention Scarcity: Challenges and Opportunities 41 CONCLUSION 42 REFERENCES 43 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS 3 | WELCOME TO SACKBOY PLANET So people build a lot of things and it’s interesting because people build a lot of things in the game but they also build a lot of things outside the game … people are building everything.