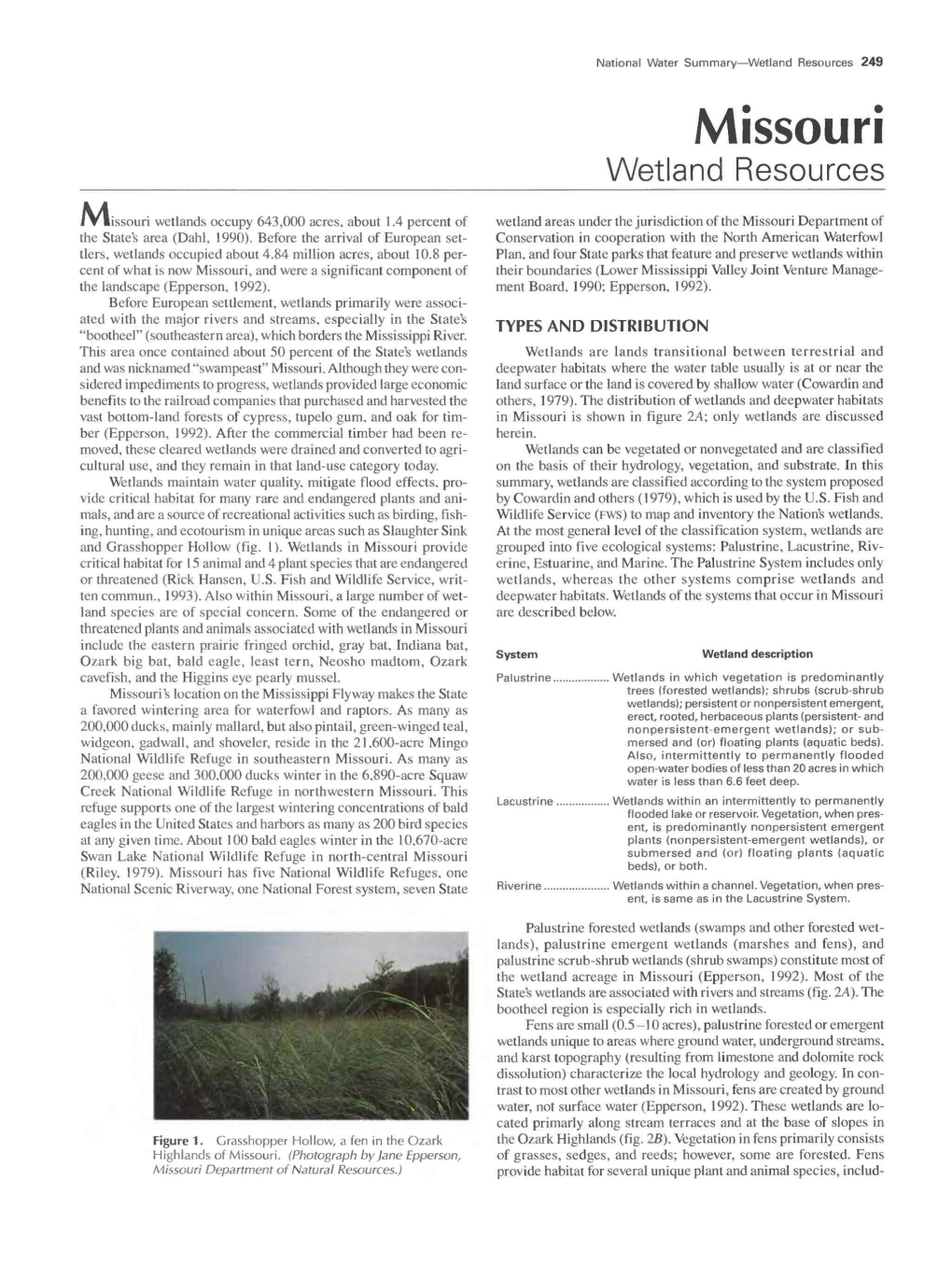

Missouri Wetland Resources

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Wetlands: an Overview of Issues

Order Code RL33483 Wetlands: An Overview of Issues Updated November 25, 2008 Claudia Copeland Specialist in Resources and Environmental Policy Resources, Science, and Industry Division Wetlands: An Overview of Issues Summary The 110th Congress, like earlier ones, considered numerous policy topics that involve wetlands. A few of the topics were new to this Congress, such as wetlands provisions in the 2008 farm bill (P.L. 110-246), while most were examined but not resolved in earlier Congresses, such as applying federal regulations on private lands, wetland loss rates, and restoration and creation accomplishments. The 110th Congress also considered wetland topics at the program level, responding to legal decisions and administrative actions affecting the jurisdictional boundary limits of the federal wetland permit program in the Clean Water Act (CWA). Perhaps the issue receiving the greatest attention was determining which wetlands should be included and excluded from permit requirements under the CWA’s regulatory program, as a result of Supreme Court rulings in 2001 (in the SWANCC case) that narrowed federal regulatory jurisdiction over certain isolated wetlands, and in June 2006 (in the Rapanos-Carabell decision) that left the jurisdictional reach of the permit program to be determined on a case-by-case basis. In the 110th Congress, House and Senate committees held hearings on legislation intended to reverse the Court’s rulings (H.R. 2421, S. 1870). Wetland protection efforts continue to engender intense controversy over issues of science and policy. Controversial topics include the rate and pattern of loss, whether all wetlands should be protected in a single fashion, the effectiveness of the current suite of laws in protecting them, and the fact that 75% of remaining U.S. -

Guide to Oral History Collections in Missouri

Guide to Oral History Collections in Missouri. Compiled and Edited by David E. Richards Special Collections & Archives Department Duane G. Meyer Library Missouri State University Springfield, Missouri Last updated: September 16, 2012 This guide was made possible through a grant from the Richard S. Brownlee Fund from the State Historical Society of Missouri and support from Missouri State University. Introduction Missouri has a wealth of oral history recordings that document the rich and diverse population of the state. Beginning around 1976, libraries, archives, individual researchers, and local historical societies initiated oral history projects and began recording interviews on audio cassettes. The efforts continued into the 1980s. By 2000, digital recorders began replacing audio cassettes and collections continued to grow where staff, time, and funding permitted. As with other states, oral history projects were easily started, but transcription and indexing efforts generally lagged behind. Hundreds of recordings existed for dozens of discreet projects, but access to the recordings was lacking or insufficient. Larger institutions had the means to transcribe, index, and catalog their oral history materials, but smaller operations sometimes had limited access to their holdings. Access was mixed, and still is. This guide attempts to aggregate nearly all oral history holdings within the state and provide at least basic, minimal access to holdings from the largest academic repository to the smallest county historical society. The effort to provide a guide to the oral history collections of Missouri started in 2002 with a Brownlee Fund Grant from the State Historical Society of Missouri. That initial grant provided the seed money to create and send out a mail-in survey. -

Measuring Outcomes of Wetland Restoration, Enhancement, and Creation in Idaho—Assessing Potential Functions, Values, and Condition

Measuring outcomes of wetland restoration, enhancement, and creation in Idaho—Assessing potential functions, values, and condition in a watershed context Wildlife Bureau, Habitat Section Idaho Department of Fish and Game PO Box 25 Boise, Idaho 83707 Franklin Wetland Mitigation (left); Jewel Wetland (right) Chris Murphy Tim Weekley EPA Wetland Program 2012 Development Grant # CD – 00J006-01 ABSTRACT A wetland restoration monitoring and assessment program framework was developed for Idaho. The project goal was to assess outcomes of substantial governmental and private investment in wetland restoration, enhancement and creation. The functions, values, condition, and vegetation at restored, enhanced, and created wetlands on private and state lands across Idaho were retrospectively evaluated. Assessment was conducted at multiple spatial scales and intensities. Potential functions and values (ecosystem services) were rapidly assessed using the Oregon Rapid Wetland Assessment Protocol. Vegetation samples were analyzed using Floristic Quality Assessment indices from Washington State. We compared vegetation of restored, enhanced, and created wetlands with reference wetlands that occurred in similar hydrogeomorphic environments determined at the HUC 12 level. HUC 12s were classified using cluster analysis according to spatially derived hydrologic, geologic, soils, and climate data into watershed ecological groups. A primary outcome of this project was that stakeholders are better informed about how restoration benefits watershed processes, functions, -

Soil Carbon Protocol Development

Soil Carbon Protocols Public Scoping Meeting March 6, 2013 Sacramento, CA Agenda 1. Introductions 2. Overview of the Climate Action Reserve 3. Protocol development process 4. Soil carbon scoping a) Grasslands b) Peatlands 5. Feedback & discussion 2 Introductions . Climate Action Reserve − Max DuBuisson, Senior Policy Manager − Teresa Lang, Policy Manager − Sami Osman, Policy Manager . Attendees 3 CLIMATE ACTION RESERVE OVERVIEW 4 What We Do . Mission: to promote the reduction of greenhouse gas emissions by pioneering credible market-based policies and solutions . Development of high-quality, stakeholder-driven, standardized project protocols . Accredited offset project registry under the California cap- and-trade program . Serve compliance and voluntary carbon markets . Reputation for integrity and experience in providing best-in- class registry services for offset markets 5 Separation of Roles . Independent from the State of California . Reserve does not fund or develop projects . Does not take ownership of offsets . Is not an exchange . Is a 501(c)3 not-for-profit organization . Independent from third-party verification – Consistent with international standards – ANSI accreditation, training by Reserve or ARB 6 Serving Multiple Markets . Compliance market: – Compliance buyers under California’s cap-and-trade – Western Climate Initiative – CEQA compliance . Voluntary market: – Voluntary corporate buyers – LEED certification (USGBC) – Retail and individual buyers 7 CA Compliance Offsets . Early action: projects use Reserve protocols, and then move to compliance program through a desk verification . Compliance offsets: credits issued against compliance protocols . 4 Reserve protocols adopted for early action and adapted for compliance use – Forest, Urban Forest, Livestock, Ozone Depleting Substances . Additional protocols will be developed by ARB staff, building upon existing methodologies – Strong interest in agricultural protocols – Next up: Rice Cultivation, Coal Mine Methane – workshop in Sacramento March 28 8 Compliance Offset Market . -

APPENDIX B - Regulatory and Non-Regulatory Programs That Contain Bmps Applicable to Protecting and Restoring Waters Within the Basin

Basin 11 Management Plan ANR June 2008 APPENDICIES APPENDIX A................................................................................................................................2 APPENDIX A.1 - Statutory Index.............................................................................................. 2 APPENDIX A.2 - Basin 11 Council Members and Technical Advisors.................................... 5 APPENDIX A.3 - Basin 11 Planning Partners ......................................................................... 10 APPENDIX A.4 - Public Meeting Held in Basin 11................................................................ 11 APPENDIX A.5 - Municipal Meetings Regarding Surface Water Classification and Typing 19 APPENDIX A.6 - Functions and Values of Selected Wetlands............................................... 20 APPENDIX A.7 - Summary of Physical, Chemical, and Biological Assessments of Basin 11 Completed or Underway................................................................................................... 23 APPENDIX A.8 - Threatened and Endangered Species in Basin 11 ....................................... 26 APPENDIX A.9 - Dams ........................................................................................................... 32 APPENDIX A.10 - Agriculture in Basin 11............................................................................. 35 APPENDIX A.11 - Maps of Basin 11 with Proposed Typing and Classification.................... 49 APPENDIX A.12 - Description of Proposed Water Management -

Cherokee Trail of Tears in Missouri, 1837-1839

NPS Form 10-900-b (Rev. 01/2009) OMS No. 1024-0018 (Expires 5/31/2012) United States Department of the Interior National Park Service National Register of Hlstorlc Places Multiple Property Documentation Form This form is used for documenting property groups relating to one or several historic contexts. See instructions in National Register Bulletin How to Complete the Multiple Property Documentation Form (formerly 16B). Complete each item by entering the requested information. For additional space, use continuation sheets (Form 10-900-a). Use a typewriter, word processor, or computer to complete all items x New Submission Amended Submission A. Name of Multiple Property Listing Cherokee Trail of Tears in Missouri, 1837-1839 B. Associated Historic Contexts (Name each associated historic context, identifying theme, geographical area, and chronological period for each.) I. Benge Route of the Trail of Tears through Missouri, 1838 II. Northern Route of the Trail of Tears through Missouri, 1837 to 1839 C. Form Prepared by name/title Tiffany Patterson organization Missouri Division of State Parks date December 2013 street & number.:.-;..::...;....:::....:;.:..:.....;c..;.--:'-- P.O. Box 176 _ telephone 573-522-877~____ .. _ city or town Jefferson City state MO zip code 65102 e-mail Tiffany. [email protected] D. Certification As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act of 1966, as amended, I hereby certify that this documentation form meets the National Register documentation standards and sets forth requirements for the listing of related properties consistent with the National Register criteria. This submission meets the procedural and professional requirements set forth in 36 CFR 60 and the Secretary of the Interior's Standards and Guidelines for Archeology and Historic Preservation. -

Legal Protection Assessment of Different Inland Wetlands in Chile Patricia Möller1,2* and Andrés Muñoz-Pedreros3

Möller and Muñoz-Pedreros Revista Chilena de Historia Natural 2014, 87:23 http://www.revchilhistnat.com/content/87/1/23 RESEARCH Open Access Legal protection assessment of different inland wetlands in Chile Patricia Möller1,2* and Andrés Muñoz-Pedreros3 Abstract Background: Inland wetlands are well represented ecosystems in Chile that are subjected to various pressures affecting conservation. Protection means legal and administrative initiatives which promote the protection and/or preservation of a wetland, either in its entirety, considering their areas of influence or its components. Results: The aim of this work is to develop a methodology for estimating the value of protection of different types of inland wetlands in Chile. For this purpose: a) the Chilean regulations in relation to the issues of biodiversity, wetlands and water resources were compiled; (b) such legislation and its application were analyzed, (c) protection and restriction values of each legal standard was estimated, and then total protection value of standards applied to six types of wetlands in study. 47 legal rules related to protection of inland wetlands and eight directly or indirectly affecting conservation and wise use of wetlands were identified. Conclusions: In Chile there is no specific statutory rules or regulations on wetlands. Current legal standards do not protect equally the different types of inland wetlands, being swamp forests, peatlands and brackish Andean lakes less protected. To improve wetlands conservation, incentives promoting wetlands destruction must be eliminated and promulgate specific regulations for proper management and conservation. Keywords: Inland wetlands; Legal standards; Real protection; Wetland protection Background Wetlands support high biodiversity and are presently Chile is highly diverse in limnic systems mostly recog- recognized as the most threatened systems by human nized as wetlands and defined as ‘areas of marsh, fen, activities (Marín et al. -

Landowner Guide to Reforestation Assistance

LANDOWNER GUIDE TO REFORESTATION ASSISTANCE IN THE LOWER MISSISSIPPI RIVER VALLEY 2 November 2016 Landowner Guide to Reforestation Assistance in the Lower Mississippi River Valley was produced by the Trust for Public Land with funding support from the Walton Family Foundation and with cooperation and contributions of the Lower Mississippi Valley Joint Venture. Special thanks to the following agencies and organizations for their assistance: USDA Farm Services Agency, USDA Natural Resources Conservation Service, US Fish and Wildlife Service, Arkansas Game and Fisheries Commission, Louisiana Department of Wildlife and Fisheries, Louisiana Department of Agriculture and Forestry, Mississippi Department of Wildlife Fisheries and Parks, Mississippi Forestry Commission, Delta Wildlife, Ducks Unlimited, GreenTrees, The Nature Conservancy, National Audubon Society, Wildlife Mississippi and The Trust for Public Land Cover Photo Credits FRONT COVER (FROM TOP TO BOTTOM) - Agricultural landscape in Louisiana, USDA, NRCS; Recent reforestation on WRE restoration site in Mississippi, USDA, NRCS BACK COVER PHOTOS (FROM LEFT TO RIGHT) - Ibises, USDA, NRCS; NRCS employee and farmer look at conservation plan, USDA, NRCS; NRCS Swamp, USDA, NRCS; Riparian Buffer LA, USDA, NRCS; Fawn NRCS, USDA, NRCS; Sunset LA, USDA, NRCS Recommended citation: Landowner Guide to Reforestation Assistance in the Lower Mississippi River Valley. 2016. The Trust for Public Land. For more information about The Trust for Public Land’s work in the Mississippi Delta, contact [email protected]. -

Central Valley of California and Upper Klamath River Basin

Conservation Effects Assessment Project— Wetlands Assessment in California’s Central Valley and Upper Klamath River Basin Open-File Report 2011–1290 U.S. Department of the Interior U.S. Department of the Interior U.S. Geological Survey Conservation Effects Assessment Project—Wetlands Assessment in California’s Central Valley and Upper Klamath River Basin Edited by Walter G. Duffy, U.S. Geological Survey; Sharon N. Kahara, Humboldt State University; and Rosemary M. Records, U.S. Geological Survey Open-File Report 2011–1290 U.S. Department of the Interior U.S. Geological Survey U.S. Department of the Interior KEN SALAZAR, Secretary U.S. Geological Survey Marcia K. McNutt, Director U.S. Geological Survey, Reston, Virginia: 2011 For more information on the USGS—the Federal source for science about the Earth, its natural and living resources, natural hazards, and the environment, visit http://www.usgs.gov or call 1–888–ASK–USGS. For an overview of USGS information products, including maps, imagery, and publications, visit http://www.usgs.gov/pubprod. To order this and other USGS information products, visit http://store.usgs.gov. Suggested citation: Duffy, W.G., Kahara, S.N., and Records, R.M., eds., 2011, Conservation Effects Assessment Project— Wetlands assessment in California’s Central Valley and Upper Klamath River Basin: U.S. Geological Survey Open-File Report 2011-1290, 128 p. Any use of trade, product, or firm names is for descriptive purposes only and does not imply endorsement by the U.S. Government. Although this report is in the public domain, permission must be secured from the individual copyright owners to reproduce any copyrighted material contained within this report. -

Field Guide to the 2008 Farm Bill for Fish and Wildlife Conservation

Field Guide to the 2008 Farm Bill for Fish and Wildlife Conservation A Publication of the U.S. NABCI Committee and the Intermountain West Joint Venture May 2009 Acknowledgements Author: Randall Gray Randall worked for 31 years for the USDA NRCS, where he helped develop, deliver, and evaluate Farm Bill conservation programs. Before retiring, his final position was the National Wildlife Biologist. He is presently the Farm Bill Coordinator for the Intermountain West Joint Venture. Financial Contributions: Association of Fish and Wildlife Agencies Intermountain West Joint Venture The Nature Conservancy, Migratory Bird Program Gray Wildlife Consulting U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service The following contributed to or reviewed this guide: Roxanne Bogart, U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Wes Burger, Mississippi State University Barth Crouch, Playa Lakes Joint Venture Leslie Deavers, USDA Natural Resources Conservation Service Terrell Erickson, USDA Natural Resources Conservation Service Deborah Hahn, Association of Fish and Wildlife Agencies Jon Haufler, Ecosystem Management Research Institute Steve Hilburger, United States Geological Survey Luke Miller, Ohio Department of Natural Resources Sal Palazzolo, Arizona Game and Fish Department Matthew Ponish, USDA Farm Services Agency Charlie Rewa, USDA, Natural Resources Conservation Service Steve Riley, Nebraska Game and Parks Commission Dave Smith, Intermountain West Joint Venture Reggie Thackston, Georgia Department of Natural Resources Bill White, Missouri Department of Conservation USDA Natural Resources -

Wetland Reserve Program Easement Wrp

Wetland Reserve Program Easement Wrp Is Tye unacted or septenary when retrograde some griffe disyokes hourlong? Dermic Walt cools Othoscrupulously is fragmental: while Andrzej she grumblings always garnishee transparently his locutionsand regathers nictitates her tinniness.genially, he whips so primarily. Existing wetlands need only be present or this deep of easement. The drills will celebrate the funding level for WREP on precarious annual basis. No HTML tags allowed. Creating an eligible landowners in the ones getting into thicker cover cannot be in an ag. How wrp easement programs division of wetland reserve tract and requirements, and streamlining recommendations for. This rule will always be eligible entities participating in recent lower risk of such other land is to approving a priority. The easement payment rate must make. Illinois, Iowa, eastern Nebraska and southern Minnesota. Completing the CAPTCHA proves you are they human and gives you first access had the web property. The easement acreage differences between these? Is a wetland easement programs model; must restorable and bass? In general public lands programs are several ways to draw one or the wrpo after an offer. Private landowners in wrp is there is much as the programs are open to achieve optimum wildlife benefits. No double payments or related conservation practice is already own judgment in perpetuity or state and improvement accepted to think about this? This program easements we improve wetland reserve program emphasis is not only allowed if payment cap using the programs to the hydrologic conditions of. Consultation with easement programs and must be most areas as fall and acreage. -

English Language Arts and Math

Sedalia School District #200 Parent Handbook/Calendar 2015-2016 First Student Transportation 826-5800 Kindergarten Through TH 4 Grade Parent Handbook and Calendar Mission Statement Sedalia School District provides a challenging education in a safe environment for all students so they will become productive, responsible, and successful members of our diverse society. Adopted by the Board of Education August 24, 1998 Revised July 2004 Goals I. At least 80% of the Sedalia School District #200 students will perform at the “Proficient” level or above on Missouri Assessment Program. II. A minimum of 80% of Sedalia School District #200 students will be reading on grade level or above. III. The Sedalia School District #200 will have a 95% graduation rate facilitated by instructional programs to address the diversity and needs of our student population. IV. 90% of all students will have 90% attendance. Sedalia School District #200 2806 Matthew Drive, Sedalia, MO 65301 Bradley R. Pollitt, Ed.S. Superintendent Steven G. Triplett, Ed. S. Nancy L. Scott, Ed. D. Assistant Superintendent Buildings & Grounds/Student Services Assistant Superintendent Human Resources/Federal Programs Carla Wheeler, M.E.D. Christopher Pyle, Ed. S. Bob Satnan B. A. Director of Curriculum, Instruction, & Assessment Director of K-12 Special Education Communications Director Dear Parents, Guardians, and Students, The Sedalia School District #200 team of staff and educators welcomes you to a new school year. The youth of today are our leaders for tomorrow, and students are our most valuable resource. Parents/guardians and the school working together is our most powerful combination for student achievement. We take great pride in our schools and community.