A Review of the Distribution and Size of Prion (Pachyptila Spp.) Colonies Throughout New Zealand

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

First Record of a Broad-Billed Prion Pachyptila Vittata at Coronation Island, South Orkney Islands

Blight & Woehler: First record of a Broad-billed Prion at Coronation Island 191 FIRST RECORD OF A BROAD-BILLED PRION PACHYPTILA VITTATA AT CORONATION ISLAND, SOUTH ORKNEY ISLANDS LOUISE K. BLIGHT1,2 & ERIC J. WOEHLER3 1Procellaria Research and Consulting, 944 Dunsmuir Road, Victoria, British Columbia, V9A 5C3, Canada 2Current address: Centre for Applied Conservation Research, University of British Columbia, Vancouver, British Columbia, V6T 1Z4, Canada ([email protected]) 3School of Zoology, University of Tasmania, Hobart, Tasmania, 7005, Australia Received 15 April 2008, accepted 2 August 2008 The known breeding distribution of Broad-billed Prions Pachyptila or as a bird blown out of its normal at-sea range by strong winds vittata is restricted to Tristan da Cunha and Gough Islands in the during poor weather. Alternatively, there may be low numbers of South Atlantic Ocean and to offshore islands around New Zealand Broad-billed Prions breeding at poorly-surveyed sub-Antarctic and the Snares and Chatham Islands, with the range at sea believed colonies, such as the South Orkney Islands. Antarctic Prions are one to extend to coastal South Africa in the South Atlantic Ocean and of the most numerous seabird species in the Antarctic (Marchant & near-shore waters around New Zealand (Marchant & Higgins 1990). Higgins 1990); they nest in the South Orkney Islands (Marchant & The taxonomy of prions remains controversial, with most authors Higgins 1990). It is possible that low numbers of breeding Broad- recognising up to six species, but varying numbers of subspecies. billed Prions have been overlooked amongst their congeners. The at-sea ranges of many Southern Ocean seabird species are Although no sympatric breeding sites are known for the two species still incompletely described, with relatively few surveys obtaining (Shirihai 2002) and the presence of this bird may have been an at-sea data for prions. -

Birdlife Australia Rarities Committee Unusual Record Report Form

BirdLife Australia Rarities Committee Unusual Record Report Form This form is intended to aid observers in the preparation of a submission for a major rarity in Australia. (It is not a mandatory requirement) Please complete all sections ensuring that you attach all relevant information including any digital images (email to [email protected] or [email protected]). Submissions to BARC should be submitted electronically wherever possible. Full Name: Rob Morris Office Use Address: Phone No: Robert P. Morris, Email: Full Name: Andrew Sutherland (first noticed the second bird) Address: Phone No: Email: Species Name: Broad-billed Prion Scientific Name: Pachyptila vittata Date(s) and time(s) of observation: 11 August 2019 First individual photographed at 12.22 – last bird photographed at 13.11. How long did you watch the bird(s)? c30+ minutes – multiple sightings of 2 birds (possibly 3) and then an additional sighting of 1 bird 20 minutes later whilst travelling, flying past and photographed. First and last date of occurrence: 11 August 2019 Distance to bird: Down to approximately 20-30 m Site Location: SE Tasmania. Approximately 42°50'36.30"S 148°24'46.23"E 22NM ENE of Pirates Bay, Eaglehawk Neck. We went north in an attempt to seek lighter winds and less swell and avoid heading straight into the strong SE winds and southerly swell. Habitat (describe habitat in which the bird was seen): Continental slope waters at a depth of approximately 260 fathoms. Sighting conditions (weather, visibility, light conditions etc.): Weather: Both days were mostly cloudy with occasional periods of bright sunshine. -

DIET and ASPECTS of FAIRY PRIONS BREEDING at SOUTH GEORGIA by P.A

DIET AND ASPECTS OF FAIRY PRIONS BREEDING AT SOUTH GEORGIA By P.A. PRINCE AND P.G. COPESTAKE ABSTRACT A subantarctic population of the Fairy Prion (Pachyprzla turtur) was studied at South Georgia in 1982-83. Full measurements of breeding birds are given, together with details of breeding habitat, the timing of the main breeding cycle events, and chick growth (weight and wing, culmen and tarsus length). Regurgitated food samples showed the diet to be mainly Crustacea (96% by weight), fish and squid comprising the rest. Of crustaceans, Antarctic krill made up 38% of items and 80% by weight. Copepods (four species, mostly Rhincalanus gigas) made up 39% of items but only 4% by weight; amphipods [three species, principally Themisto gaudichaudii made up 22% of items and 16% by weight. Diet and frequency of chick feeding are compared with those of Antarctic Prions and Blue Petrels at the same site; Fairy Prions are essentially intermediate. INTRODUCTION The Fairy Prion (Pachyptila turtur) is one of six members of a genus confined to the temperate and subantarctic regions of the Southern Hemisphere. With the Fulmar Prion (P. crassirostris), it forms the subgenus Pseudoprion. Its main area of breeding distribution is between the Antarctic Polar Front and the Subtropical Convergence. It is widespread in the New Zealand region, from the north of the North Island south to the Antipodes Islands and Macquarie Island, where only about 40 pairs survive (Brothers 1984). Although widespread in the Indian Ocean at the Prince Edward, Crozet and Kerguelen Islands, in the South Atlantic Ocean it is known to breed only on Beauchene Island (Falkland Islands) (Strange 1968, Smith & Prince 1985) and South Georgia (Prince & Croxall 1983). -

Krill Caught by Predators and Nets: Differences Between Species and Techniques

MARINE ECOLOGY PROGRESS SERIES Vol. 140: 13-20. 1996 Published September 12 Mar Ecol Prog Ser Krill caught by predators and nets: differences between species and techniques K. Reid*, P. N. Trathan, J. P. Croxall, H. J. Hill British Antarctic Survey, Natural Environment Research Council, High Cross. Madingley Road, Cambridge CB3 OET, United Kingdom ABSTRACT. Samples of Antarchc krill collected from 6 seabird species and Antarctic fur seal dunng February 1986 at South Georgia were compared to krill from scientific nets fished in the area at the same time. The length-frequency d~stributionof krill was broadly similar between predators and nets although the krill taken by diving species formed a homogeneous group wh~chshowed significant dif- ferences from knll taken by other predators and by nets There were significant differences In the maturity/sex stage composition between nets and predators; in particular all predator species showed a consistent sex bias towards female krill. Similarities in the knll taken by macaroni [offshore feeding) and gentoo (inshore feeding) penguins and differences between krill taken by penguins and alba- trosses suggest that foraging techniques were more important than foraging location in influencing the type of krill in predator diets. Most krill taken by predators were adult; most female krill were sexually active (particularly when allowance is made for lnisclassification bias arising from predator digestion). Because female krill are larger, and probably less manouverable, than males, the biased sex ratio In predator diets at thls t~meof year may reflect some comblnat~onof selectivity by predators and superior escape responses of male krill. -

Salvin's Prion Pachyptila Salvini Captured Alive on Beach at Black Rocks, Victoria, 27Th July 1974

1 Salvin’s Prion Pachyptila salvini captured alive on beach at Black Rocks, Victoria, 27th July 1974 by Mike Carter Fig. 1. Ailing Salvin’s Prion captured alive on beach at Black Rocks, Victoria, 27 July 1974 During a gale on 27th July 1974, a Salvin’s Prion was observed flying over the breakers just beyond the rocks on the beach at Black Rocks, Victoria. Obviously debilitated, it came ashore and sought refuge in rock pools. It was rescued but died within five hours. This observation was made by a group of local and international seabird enthusiasts that included Dr Bill Bourne (from the UK), Gavin Johnstone & Noels Kerry from the Australian Antarctic Division, Peter Menkhorst, Richard Loyn, Paul Chick and me. Overseas and interstate visitors had joined locals to attend an International Ornithological Congress in Melbourne. The attached photos are recent digital copies of transparencies taken immediately after capture. Dimensions in mm measured as described in Marchant & Higgins (1990) on 29-07-74. (L = left, R = right), Wing 191; Tail 94; Tarsus (L) 36.4, (R) 35.9; Middle toe (L) 45.2, (R) 45.7; Claw (L) 8.8, (R) 8.0. Culmen (C) 31.8; Width (W) 16.4; Ratio (C)/ (W) 1.94: Bill depth max 13.2; Bill depth min 7.2. Apparent bulk = 1/4CW(BDmax+BDmin) = 2661 cub mm. I find this generated number to be a good discriminator for identifying Victorian prion corpses. 2 Figs. 2 to 5. Ailing Salvin’s Prion captured alive on beach at Black Rocks, Victoria, 27 July 1974 Identification Identification at the time was based mainly on information in Serventy, Serventy & Warham (1971). -

Olfactory Foraging by Antarctic Procellariiform Seabirds: Life at High Reynolds Numbers

Reference: Biol. Bull. 198: 245–253. (April 2000) Olfactory Foraging by Antarctic Procellariiform Seabirds: Life at High Reynolds Numbers GABRIELLE A. NEVITT Section of Neurobiology, Physiology and Behavior, University of California, Davis, California 95616 Abstract. Antarctic procellariiform seabirds forage over (Chelonia mydas) nesting on Ascension Island in the middle vast stretches of open ocean in search of patchily distributed of the Atlantic Ocean are guided there from feeding grounds prey resources. These seabirds are unique in that most off the coast of South America, presumably by a redundant species have anatomically well-developed olfactory systems set of mechanisms that possibly includes an ability to smell and are thought to have an excellent sense of smell. Results their island birth place (for review, see Lohmann, 1992). from controlled experiments performed at sea near South To explain such behaviors, it is commonly assumed that Georgia Island in the South Atlantic indicate that different animals are able to recognize and follow odors emanating species of procellariiforms are sensitive to a variety of from a distant source. This logic predicts that a recognizable scented compounds associated with their primary prey. odor signature emanates from a site, forming a gradient that These include krill-related odors (pyrazines and trimethyl- can be detected thousands of kilometers away. By some amine) as well as odors more closely associated with phy- adaptive behavioral mechanism such as turning or swim- toplankton (dimethyl sulfide, DMS). Data collected in the ming upstream in response to the odor cue, the animal context of global climatic regulation suggest that at least focuses its directional movement to locate the source of the one of these odors (DMS) tends to be associated with odor plume. -

Part II: Parasite List by Parasite

Surveillance Vol.25 Special Issue 1998 Parasites of Birds in New Zealand Part II: Parasite list by parasite Ectoparasite Host Ectoparasite _- Host Feather mites Antrlges sp ~ continued Allopt~ssp Gull, Red-billed Chaff i11 ch Gannet, Australasian Creeper, Brown Shearwater, Flesh-footed Morepork Booby, Masked (Blue-faced) Sparrow, House Booby, Brown Saddleback, South Island Plover, Shore Tu i Sparrow, Hedge Alloptes hisetatus Tern, Caspian Canary Alloptes phaetontis minor Tropicbird, Red-tailed Quail, Brown Petrel, White-naped Blackbird Thrush, Song Allopres phaeton tis simplex Tropicbird, Red-tailed Andgopsis paxserinus Myna, Common Starling Alloptes stercorurii Skua, Arctic Anheniialges sp Fantail, South Island Ana1ge.r sp Myna, Common Fantail, North Island Skylark Greenfinch Brephosceles sp Dotterel, New Zealand Rook Mollymawk, Buller’s Parakeet, Yellow-crowned Petrel, Black-bellied Storm Yellowhammer Petrel, Northern Giant 26 Surveillance Special Issue Surveillance Vol.25 Special Issue 1998 Parasites of Birds in New Zealand Host Ectoparasite I Weka Prion, Broad-hi1 led Kea Petrel. Cook's Kakapo Pe tre I, M age11 ta (Chatham Pigeon. Rock Island Taiko) Fowl. Domestic Shearwater. Flesh-footed Shearwater, Fluttering Weka Wcka I lot t c re I. Banded Pheasant, Ring-necked Pctrcl. White-naped Pipn. New Zealand Petrel . W hi te-naped Dotterel, New Zealand Pukeko Shearwater. Sooty Rail, Banded Ovstercatcher. South Island Greenfinch Sparrow. HOLIX Pkd Stilt. Australasian Pied Kokako. South Island Stilt. Blach Weka Plover, Shore Kakapo S iIvere ye Pigeon, New Zealand Petrel. White-napcd Pukeko Petrel. Cook's Rail. Banded Petrel. Black-winged Shag. Little Petrel. Pycroft's Shag. Little Black (Little Shag, Campbell Island Black Cormorant) Shag, Stewart Island. -

Breeding Colonies Distribution for Fulmar Prion Lineage.Docx

To view this as a map and many more go to: www.nabis.govt.nz web mapping tool Type the map name into: Search for a map layer or place Lineage – Scientific methodology Breeding distribution of Fulmar prion 1. A “breeding colony” for New Zealand seabirds is defined as “any location where breeding has been reported and is considered by the expert compiling the species account to have occurred at that location at least until 1998”. 2. An “occasional breeding colony” for New Zealand seabirds is defined as “any location where breeding has been reported, but not necessarily continuously nor during consecutive breeding seasons, and is considered by the expert compiling the species account to have occurred at that location during the last 30 years”. 3. Literature sources were searched for breeding distribution information. a. Scientific papers, published texts, unpublished reports and university theses available to the expert who prepared the distributional layers. b. Aquatic Sciences and Fisheries Abstracts 1960-2010. c. OSNZ News and Southern Bird for 1977–2010. 4. Other sources. a. Nil. 5. All breeding colonies of fulmar prions are mapped according to written descriptions of their locations. The locations of the Chatham and Auckland Islands colonies are taken from the descriptions in Taylor (2000), those of the Bounty Islands from Robertson & van Tets (1982), and those of the Snares Western Chain colonies from Miskelly (1984). The colonies have not been surveyed for mapping purposes, and the mapping presented is based on the written descriptions of their locations. 6. Summary a. An expert scientist integrated information from the literature and expert opinion, and produced hand-drawn distributional zones on a template map. -

Amphipod-Based Food Web: Themisto Gaudichaudii Caught in Nets and by Seabirds in Kerguelen Waters, Southern Indian Ocean

MARINE ECOLOGY PROGRESS SERIES Vol. 223: 261–276, 2001 Published November 28 Mar Ecol Prog Ser Amphipod-based food web: Themisto gaudichaudii caught in nets and by seabirds in Kerguelen waters, southern Indian Ocean Pierrick Bocher1, 2, Yves Cherel1,*, Jean-Philippe Labat3, Patrick Mayzaud3, Suzanne Razouls4, Pierre Jouventin1, 5 1Centre d’Etudes Biologiques de Chizé, UPR-CNRS 1934, 79360 Villiers-en-Bois, France 2Laboratoire de Biologie et Environnement Marins, EA 1220 de l'Université de La Rochelle, 17026 La Rochelle Cedex, France 3Laboratoire d'Océanographie Biochimique et d’Ecologie, ESA 7076-CNRS/UPMC LOBEPM, Observatoire Océanologique, BP 28, 06230 Villefranche-sur-Mer, France 4Observatoire Océanologique, UMR-CNRS/UPMC 7621, Laboratoire Arago, 66650 Banyuls-sur-Mer, France 5Centre d’Ecologie Fonctionnelle et Evolutive, UPR-CNRS 9056, 1919 Route de Mende, 34293 Montpellier Cedex 5, France ABSTRACT: Comparing food samples from diving and surface-feeding seabirds breeding in the Golfe du Morbihan at Kerguelen Islands to concurrent net samples caught within the predator forag- ing range, we evaluated the functional importance of the hyperiid amphipod Themisto gaudichaudii in the subantarctic pelagic ecosystem during the summer months. T. gaudichaudii occurred in high densities (up to 61 individuals m-3) in the water column, being more abundant within islands in the western part of the gulf than at open gulf and shelf stations. The amphipod was a major prey of all seabird species investigated except the South Georgian diving petrel, accounting for 39, 80, 68, 59 and 46% of the total number of prey of blue petrels, thin-billed prions, Antarctic prions, common div- ing petrels and southern rockhopper penguins, respectively. -

Preparations for the Eradication of Mice from Gough Island: Results of Bait Acceptance Trials Above Ground and Around Cave Systems

Cuthbert, R.J.; P. Visser, H. Louw, K. Rexer-Huber, G. Parker, and P.G. Ryan. Preparations for the eradication of mice from Gough Island: results of bait acceptance trials above ground and around cave systems Preparations for the eradication of mice from Gough Island: results of bait acceptance trials above ground and around cave systems R. J. Cuthbert1, P. Visser1, H. Louw1, K. Rexer-Huber1, G. Parker1, and P. G. Ryan2 1Royal Society for the Protection of Birds, The Lodge, Sandy, Bedfordshire, SG19 2DL, United Kingdom. <[email protected]>. 2DST/NRF Centre of Excellence at the Percy FitzPatrick Institute, University of Cape Town, Rondebosch 7701, South Africa. Abstract Gough Island, Tristan da Cunha, is a United Kingdom Overseas Territory, supports globally important seabird colonies, has many endemic plant, invertebrate and bird taxa, and is recognised as a World Heritage Site. A key threat to the biodiversity of Gough Island is predation by the introduced house mouse (Mus musculus), as a result of which two bird species are listed as Critically Endangered. Eradicating mice from Gough Island is thus an urgent conservation priority. However, the higher failure rate of mouse versus rat eradications, and smaller size of islands that have been successfully cleared of mice, means that trials on bait acceptance are required to convince funding agencies that an attempted eradication of mice from Gough is likely to succeed. In this study, trials of bait acceptance were undertaken above ground and around cave systems that are potential refuges for mice during an aerial application of bait. Four trials were undertaken during winter, with rhodamine-dyed, non-toxic bait spread by hand at 16 kg/ha over 2.56 ha centred above cave systems in Trials 1-3 and over 20.7 ha and two caves in Trial 4. -

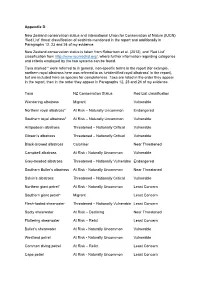

Appendix D New Zealand Conservation Status And

Appendix D New Zealand conservation status and International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) ‘Red List’ threat classification of seabirds mentioned in the report and additionally in Paragraphs 12, 23 and 24 of my evidence. New Zealand conservation status is taken from Robertson et al. (2013), and ‘Red List’ classification from http://www.iucnredlist.org/, where further information regarding categories and criteria employed by the two systems can be found. Taxa marked * were referred to in general, non-specific terms in the report (for example, northern royal albatross here was referred to as ‘unidentified royal albatross’ in the report), but are included here as species for completeness. Taxa are listed in the order they appear in the report, then in the order they appear in Paragraphs 12, 23 and 24 of my evidence. Taxa NZ Conservation Status Red List classification Wandering albatross Migrant Vulnerable Northern royal albatross* At Risk – Naturally Uncommon Endangered Southern royal albatross* At Risk – Naturally Uncommon Vulnerable Antipodean albatross Threatened – Nationally Critical Vulnerable Gibson’s albatross Threatened – Nationally Critical Vulnerable Black-browed albatross Coloniser Near Threatened Campbell albatross At Risk - Naturally Uncommon Vulnerable Grey-headed albatross Threatened – Nationally Vulnerable Endangered Southern Buller’s albatross At Risk - Naturally Uncommon Near Threatened Salvin’s albatross Threatened – Nationally Critical Vulnerable Northern giant petrel* At Risk - Naturally Uncommon Least Concern -

Conservation Status of New Zealand Birds, 2008

Notornis, 2008, Vol. 55: 117-135 117 0029-4470 © The Ornithological Society of New Zealand, Inc. Conservation status of New Zealand birds, 2008 Colin M. Miskelly* Wellington Conservancy, Department of Conservation, P.O. Box 5086, Wellington 6145, New Zealand [email protected] JOHN E. DOWDING DM Consultants, P.O. Box 36274, Merivale, Christchurch 8146, New Zealand GRAEME P. ELLIOTT Research & Development Group, Department of Conservation, Private Bag 5, Nelson 7042, New Zealand RODNEY A. HITCHMOUGH RALPH G. POWLESLAND HUGH A. ROBERTSON Research & Development Group, Department of Conservation, P.O. Box 10420, Wellington 6143, New Zealand PAUL M. SAGAR National Institute of Water & Atmospheric Research, P.O. Box 8602, Christchurch 8440, New Zealand R. PAUL SCOFIELD Canterbury Museum, Rolleston Ave, Christchurch 8001, New Zealand GRAEME A. TAYLOR Research & Development Group, Department of Conservation, P.O. Box 10420, Wellington 6143, New Zealand Abstract An appraisal of the conservation status of the post-1800 New Zealand avifauna is presented. The list comprises 428 taxa in the following categories: ‘Extinct’ 20, ‘Threatened’ 77 (comprising 24 ‘Nationally Critical’, 15 ‘Nationally Endangered’, 38 ‘Nationally Vulnerable’), ‘At Risk’ 93 (comprising 18 ‘Declining’, 10 ‘Recovering’, 17 ‘Relict’, 48 ‘Naturally Uncommon’), ‘Not Threatened’ (native and resident) 36, ‘Coloniser’ 8, ‘Migrant’ 27, ‘Vagrant’ 130, and ‘Introduced and Naturalised’ 36. One species was assessed as ‘Data Deficient’. The list uses the New Zealand Threat Classification System, which provides greater resolution of naturally uncommon taxa typical of insular environments than the IUCN threat ranking system. New Zealand taxa are here ranked at subspecies level, and in some cases population level, when populations are judged to be potentially taxonomically distinct on the basis of genetic data or morphological observations.