Trends in the Epidemiology of Brucellosis in a Highly Burdened

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Alexandria's Hinterland

Alexandria’s Hinterland Archaeology of the Western Nile Delta, Egypt Mohamed Kenawi Archaeopress Archaeology Archaeopress Gordon House 276 Banbury Road Oxford OX2 7ED www.archaeopress.com ISBN 978 1 78491 014 3 ISBN 978 1 78491 015 0 (e-Pdf) © Archaeopress and M Kenawi 2014 Front cover: Baths, Kom al-Ahmer (Mohamed Kenawi); Kom Wasit, Aerial photo 2014 (copyright Italian Mission in Beheira, photographer Henrik Brahe. http://www.caiecentroarcheologico.org/ and http://www.komahmer.com/). All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the copyright owners. Printed in England by CMP (UK) Ltd This book is available direct from Archaeopress or from our website www.archaeopress.com This work is dedicated to Mariette de Vos Raaijmakers Emanuele Papi Contents List of Figures ����������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������� iii List of Plates ����������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������� viii List of Maps ������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������ viii List of Tables ����������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������� -

Efficiency of the Using of Human and Machine the Sources in Wheat Production in Beheira Governorate

Available online at http://www.journalijdr.com International Journal of Development Research ISSN: 2230-9926 Vol. 11, Issue, 07, pp. 48934-48940, July, 2021 https://doi.org/10.37118/ijdr.22437.07.2021 RESEARCH ARTICLE OPEN ACCESS EFFICIENCY OF THE USING OF HUMAN AND MACHINE THE SOURCES IN WHEAT PRODUCTION IN BEHEIRA GOVERNORATE Ashraf M. El Dalee1,*, Lamis F. Elbahenasy2, Safaa M. Elwakeel2 and Eman A. Ibrahim3 1Professor Researcher, Agricultural Economics Research Institute, Agricultural Research Center –Egypt 2Senior Researcher, Agricultural Economics Research Institute Agricultural Research Center – Egypt 3Researcher, Agricultural Economics Research Institute, Agricultural Research Center – Egypt ARTICLE INFO ABSTRACT The research problem is represented in the high costs of producing wheat crop as a result of the high prices of Article History: production requirements, which may affect the cultivated areas of it, and due to the rapid and successive Received 20th April, 2021 progress in the transfer of technology in the field of agriculture, especially agricultural operations, it has been Received in revised form possible to replace human work with automated work, after the high wages of rural labor trained women in the 10th May, 2021 fields of agriculture and continuous migration to urban areas as a result of the seasonality of agricultural Accepted 30th June, 2021 production on the one hand, and the low wages in the country side compared to the urban ones, which Published online 28th July, 2021 prompted farmers to move towards using -

Shereif Hassan Mahmoud

Hydroclimate Changes to Arid regions subjected to Impact of climate change, human activities, and Large-scale climate patterns by Shereif Hassan Mahmoud A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Water Resources Engineering Department of Civil and Environmental Engineering University of Alberta © Shereif Hassan Mahmoud, 2020 Abstract In recent years, many regions worldwide have suffered from natural hazards related to the impact of human activities and climate change, such as floods and droughts, sea level rise, extreme weather events and an accelerated hydrological cycle. In Africa, the driest continent on Earth, climate change has led to more frequent occurrences of droughts of greater severity. Beside climate change, human activities have also incurred negative environmental impact which in turn has likely affected the climate at a wide range of temporal-spatial scales worldwide. For example, in the Middle East, floods of greater magnitude have been occurring more frequently in recent decades, which could be attributed partly to rapid urbanization or the effect of climate change, or both. In the Nile River basin (NRB), recurring droughts and increasing population have led to rising tension between competing users for water. Therefore, to develop more effective mitigation strategies against the potential impact of climate change, there is an urgent need to better understand changes to the hydrologic cycle of arid regions and linkage to regional climate change. The objectives of this dissertation are: 1) To investigate the potential implications of urbanization and climate change to the flood risk of Egypt and Saudi Arabia of arid climate in the Middle East. -

Developing an Instrument to Measure Penetration of Lean Thinking for Frontline Nursing Staff

IOSR Journal of Nursing and Health Science (IOSR-JNHS) e- ISSN: 2320–1959.p- ISSN: 2320–1940 Volume 7, Issue 4 Ver. VIII (Jul.-Aug. 2018), PP 83-95 www.iosrjournals.org Developing an Instrument to Measure Penetration of Lean Thinking For Frontline Nursing Staff Reem Mabrouk Abd El Rahman1, Amal Diab Ghanem Atalla2 1Faculty of Nursing, Damanhour University, El-Beheira, Egypt 2 Faculty of Nursing, Alexandria University, Alexandria, Egypt Corresponding Author: Reem Mabrouk Abd El Rahman Abstract: Background Lean thinking and management are continuous improvement management plan that design the work flow to produce improvements in safety, quality and productivity. Aim: to develop an instrument to measure penetration of lean thinking for frontline nursing staff. Methods: A methodological mixedresearch design was utilized in all hospitals that are affiliated to the Ministry of Health and Population at El-Beheira Governorate (n= 21). Subjects: Jury group (n=55), divided into two groups: academic experts (n=10) and clinical/professional experts (n=45).Tools: tool one: Frontline Lean Thinking(FLT) Instrumentand tool two: opinnionaire sheet and a demographic data sheet for study subjects. The tool development was executed based on five steps: (1) Content domain specification; (2) Item pool generation; (3) Face & content validity evaluation; (4) Reliability assessment; lastly, (5) Instrument refinement. Results: The study findings revealed that the majority of expert groups agreed on the final version of the developed FLT Instrument with the three levels, namely: organization, unit and individual with its ten sub-domains. Conclusion: the overall result from panel of experts: both academics and clinical/professional experts showed that the developed FLT Instrument has face and content validity. -

World Bank Document

The World Bank Report No: ISR16189 Implementation Status & Results Egypt, Arab Republic of Egypt National Railways Restructuring Project (P101103) Operation Name: Egypt National Railways Restructuring Project (P101103) Project Stage: Implementation Seq.No: 13 Status: ARCHIVED Archive Date: 01-Oct-2014 Country: Egypt, Arab Republic of Approval FY: 2009 Public Disclosure Authorized Product Line:IBRD/IDA Region: MIDDLE EAST AND NORTH AFRICA Lending Instrument: Specific Investment Loan Implementing Agency(ies): Key Dates Board Approval Date 17-Mar-2009 Original Closing Date 30-Sep-2015 Planned Mid Term Review Date 30-Sep-2013 Last Archived ISR Date 15-Jun-2014 Public Disclosure Copy Effectiveness Date 24-Jun-2010 Revised Closing Date 31-Mar-2017 Actual Mid Term Review Date 07-Dec-2013 Project Development Objectives Project Development Objective (from Project Appraisal Document) The objective of the Project is to improve the reliability, efficiency and safety of the railways’ services on targeted sections ofthe rail network. Has the Project Development Objective been changed since Board Approval of the Project? ● Yes No Public Disclosure Authorized Component(s) Component Name Component Cost Component 1-1: Signaling Modernization - Cairo (Arab El Raml) to Alexandria 174.50 Component 2: Renewal of track 106.00 Component 3: Modernization of Management and Operating Practices 13.50 Component 1-2: Signaling Modernization - Beni Suef to Asyut 337.00 Contingencies and front end fees 14.00 Overall Ratings Previous Rating Current Rating Progress towards achievement of PDO Moderately Satisfactory Moderately Satisfactory Public Disclosure Authorized Overall Implementation Progress (IP) Moderately Unsatisfactory Moderately Satisfactory Overall Risk Rating Substantial Substantial Implementation Status Overview Public Disclosure Copy A level I project restructuring was approved by the Board on June 25, 2014. -

A Three-Dimensional, Numerical Groundwater Flow Model of The

Fourth International Symposium on Environmental Hydrology,2005, ASCE-EG, Cairo, Egypt, INTEGRATED MANAGEMENT OF WATER RESOURCES IN WESTERN NILE DELTA 2-MANAGEMENT ٍ SCENARIOS A. M. El Molla1, M. A. Dawoud2, M. S. Hassan3, H. Abdulrahman Ewea3, R. F. Mohamed4 ABSTRACT Western Nile delta is an important area in Egypt, in which the government has later established new reclamation projects, and irrigation and drainage network. The increase in reclaimed area together with the decrease in the discharge of canals network especially in the 1980‟s lead to shortage of surface water. The Ministry of Water Resources and Irrigation (MWRI) has an overall development plan, which will increase the reclamation area to be 625,000 feddan at the western delta area before 2017. A number of management scenarios were defined. These scenarios study alternative conjunctive uses for available water resources in western Nile delta (surface water, ground water, drainage water reuse) to prevent the groundwater aquifer from depletion. The proposed scenarios studied the full completion of the development plan proposed by MWRI for western Delta area by the year 2017. The previously built and calibrated ground water flow model was used to predict the effects of various scenarios on the groundwater aquifer for the present development and for the year 2017 development plan. INTRODUCTION Western Nile delta is an important area in Egypt, which has limited water resources, although it lies on the western part of Nile Delta aquifer. Due to the increased in the area of the reclaimed lands farmers are suffering from shortage of surface water and are forced to depend on the groundwater abstraction from wells. -

LOT NUMBER RESERVE £ Postal History 1 Early Missionary Letter

1 LOT NUMBER RESERVE £ Postal history 1 Early Missionary letter dated 7 Dec 1830, Alexandria to Beyroot 59.00 2 French Consular Mail – Entire Alex to Marseilles with 40 centimes cancelled 5080 (diamond) via Paquebots de la Mediterrane (in red) and PD (in red). Reduced rate from 1866 44.00 Second Issue, 1867-69 (Nile Post numbers) 3 5-para (D8), Types 104 unused, with photograph 24.00 4 10-para (D91), used with watermark on face. ESC certificate 45.00 5 3 x 10-para (D9a, 9b, 9c), used in excellent condition with photograph 85.00 6 10-para (D9, Types 1-4), unused, includes Stone A Type 2 (D9A) 83.00 7 10-para (D9f, Types 1-4), unused, includes Stone B Type 2 unbroken O, with photograph 63.00 8 10-para (D9 Types 1-4), unused and used including Stone A 3rd State Type 2 with photograph 111.00 9 20-para (D10 Types 1-4), unused Stone A (2 dots) with photograph 72.00 10 20-para (D10i Types 1-4), unused Stone B (3 dots) with photograph 65.00 11 1-piastre (D11), 37 copies unused and used, all types. Worthy of research by a student of this issue 49.00 12 5-piastre (D 13 Types 1-4), unused, fine condition 390.00 13 5-piastre (D13 Types 1-4), used, fine condition 240.00 14 5-para (D8k) used, misplaced perforation 43.00 15 5-para (D8), yellow green, mint, very fine 19.00 16 10-para (D9j), unused, “white hole in wig” variety 29.00 17 1-piastre (D11v), unused, “inverted watermark” 19.00 18 1-piastre (D11m), unused, imperforate 22.00 Postage Due issue 1922 (Nile Post numbers) 19 PD30a, mint block of 12, overprint à cheval 186.00 20 PD30a, three mint singles, -

Lepidoptera – Noctuidae) Based on Male and Female Genitalia

Egypt. J. Agric. Res., 93 (4), 2015 1033 IDENTIFICATION OF THE EGYPTIAN SPECIES OF CUTWORM GENERA AGROTIS, NOCTUA AND SCOTIA (LEPIDOPTERA – NOCTUIDAE) BASED ON MALE AND FEMALE GENITALIA BADR, M. A.1, A. A. EL- SAEADY2, A. E. HUSSEIN2 and M. Y. HASAN1. 1. Plant Protection Reseach Institute, ARC, Dokki., Giza. 2. Plant Protection Departement, Faculty of Agric., Al-Azhar Univ., Cairo, Egypt. (Manuscript received 17 March 2015) Abstract leven cutworm species (Lepidoptera- Noctuidae) are identified here based on the general colour of moths and E the taxonomical characters of the male and female genitalia these are: Agrotis crassa (Ersch.), A. haifae herzogi (Rebel), A. ipsilon (Huf.) , A. pictifascia (Hamp.), A. pierrettii (Bug.), A. puta (H.) ,A. ripae (Baker) , A. spinifera (H.), A. trux (H.), Noctua pronuba L. and Scotia segetum (D. Sciff.). Keys to the species based on male and female genitalia are presented together with illustrations.Common names, synonyms and host records are provided. INTRODUCTION Cutworms are serious pests on the seedlings of many field crops i.e., beet root, spinach, sweet beet (Chenopodiaceae ); lettuce, (Compositae ); sweet potato, (Convolvulaceae); broccoli, cabbage, kale, rape, turnip (Cruciferae); squash, water melon , cucumber, (Cucurbitaceae); barley, corn, sorghum, sugarcane, wheat(Graminae ); alfalfa, beans, chick pea, clover, cowpea, lentil, millet, peas, soyabean, (Leguminosae); garlic, onion, (Liliaceae); cotton, okra, (Malvaceae); strawberry, (Rosacea); egg plant, potatoes, tomatoes, tobacco, (Solanaceae); and carrot, celery, dill, (Umbelliferae). etc. (after Bradley, 1967; Hill, 1975; Karoum et al, 1976; Skinner, 1984; Scholtz & Holm, 1985; Carter, 1992; Novak, 2000; Carrera – Suarez, et al, 2011; San Blas & Barrionevo 2013; Feizpoor et – al 2014 and San Blas, 2014). -

Durham E-Theses

Durham E-Theses Spatial patterns of population dynamics in Egypt, 1947-1970 El-Aal, Wassim A.E. -H. M. Abd How to cite: El-Aal, Wassim A.E. -H. M. Abd (1977) Spatial patterns of population dynamics in Egypt, 1947-1970, Durham theses, Durham University. Available at Durham E-Theses Online: http://etheses.dur.ac.uk/7971/ Use policy The full-text may be used and/or reproduced, and given to third parties in any format or medium, without prior permission or charge, for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-prot purposes provided that: • a full bibliographic reference is made to the original source • a link is made to the metadata record in Durham E-Theses • the full-text is not changed in any way The full-text must not be sold in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. Please consult the full Durham E-Theses policy for further details. Academic Support Oce, Durham University, University Oce, Old Elvet, Durham DH1 3HP e-mail: [email protected] Tel: +44 0191 334 6107 http://etheses.dur.ac.uk SPATIAL PATTERNS OF POPULATION DYNAMICS , IN EGYPT, 1947-1970 VOLUME I by Wassim A.E.-H. M. Abd El-Aal, B.A., M.A. (Graduate Society) A thesis submitted to the Faculty of Social Sciences for the degree of Doctor of PhDlosophy Uru-vorsity of Dm n?n' A.TDI 1077 The copyright of this thesis rests with the author No quotation from it should be published without his prior written consent and information derived from it should be acknowledged Professor J. -

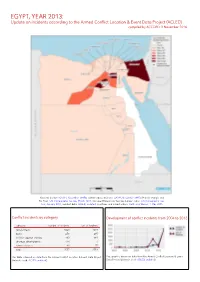

EGYPT, YEAR 2013: Update on Incidents According to the Armed Conflict Location & Event Data Project (ACLED) Compiled by ACCORD, 3 November 2016

EGYPT, YEAR 2013: Update on incidents according to the Armed Conflict Location & Event Data Project (ACLED) compiled by ACCORD, 3 November 2016 National borders: GADM, November 2015b; administrative divisions: GADM, November 2015a; Hala’ib triangle and Bir Tawil: UN Cartographic Section, March 2012; Occupied Palestinian Territory border status: UN Cartographic Sec- tion, January 2004; incident data: ACLED, undated; coastlines and inland waters: Smith and Wessel, 1 May 2015 Conflict incidents by category Development of conflict incidents from 2004 to 2013 category number of incidents sum of fatalities riots/protests 1821 1319 battle 279 495 violence against civilians 193 669 strategic developments 174 1 remote violence 90 75 total 2557 2559 This table is based on data from the Armed Conflict Location & Event Data Project This graph is based on data from the Armed Conflict Location & Event (datasets used: ACLED, undated). Data Project (datasets used: ACLED, undated). EGYPT, YEAR 2013: UPDATE ON INCIDENTS ACCORDING TO THE ARMED CONFLICT LOCATION & EVENT DATA PROJECT (ACLED) COMPILED BY ACCORD, 3 NOVEMBER 2016 LOCALIZATION OF CONFLICT INCIDENTS Note: The following list is an overview of the incident data included in the ACLED dataset. More details are available in the actual dataset (date, location data, event type, involved actors, information sources, etc.). In the following list, the names of event locations are taken from ACLED, while the administrative region names are taken from GADM data which serves as the basis for the map above. In Ad Daqahliyah, 60 incidents killing 27 people were reported. The following locations were affected: Al Mansurah, Matariya, Mit Ghamr. In Al Bahr al Ahmar, 3 incidents killing 0 people were reported. -

Catalogue of the Roman and Byzantine Baths of Egypt Thibaud Fournet, Bérangère Redon, Matthieu Vanpeene

Catalogue of the Roman and Byzantine Baths of Egypt Thibaud Fournet, Bérangère Redon, Matthieu Vanpeene To cite this version: Thibaud Fournet, Bérangère Redon, Matthieu Vanpeene. Catalogue of the Roman and Byzantine Baths of Egypt. Bérangère Redon. Collective baths in Egypt 2. New discoveries and perspectives, Presses de l’IFAO, pp.451-523, 2017, 9782724706963. hal-01758098 HAL Id: hal-01758098 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-01758098 Submitted on 7 Dec 2019 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Collective Baths in Egypt 2 25New siècles Discoveries de bainand Perspectives collectif en Orient Proche-Orient, Égypte et péninsule Arabique T H E R M A E Edited by AuteurBérangère Redon Specimen Institut français d’archéologie orientale Études urbaines 10 – 2017 Dans la même collection : Marie-Françoise Boussac, Sylvie Denoix, Thibaud Fournet et Bérangère Redon (éds.), 25 siècles de bain collectif en Orient. Proche-Orient, Égypte et péninsule Arabique, 2014. Julien Loiseau, Reconstruire la Maison du sultan (2 vol.), 2010. Marie-Françoise Boussac, Thibaud Fournet et Bérangère Redon, Le bain collectif en Égypte, 2009. István Ormos, Max Herz Pasha, (2 vol.), 2009. Mercedes Volait (éd.), Le Caire – Alexandrie. -

Kurzübersicht Über Vorfälle Aus Dem Armed Conflict Location & Event

EGYPT, FOURTH QUARTER 2016: Update on incidents according to the Armed Conflict Location & Event Data Project (ACLED) compiled by ACCORD, 8 February 2017 National borders: GADM, November 2015b; administrative divisions: GADM, November 2015a; Hala’ib triangle and Bir Tawil: UN Cartographic Section, March 2012; Occupied Palestinian Territory border status: UN Cartographic Sec- tion, January 2004; incident data: ACLED, January 2017; coastlines and inland waters: Smith and Wessel, 1 May 2015 Development of conflict incidents from December Conflict incidents by category 2014 to December 2016 category number of incidents sum of fatalities riots/protests 60 2 battle 41 230 remote violence 30 163 violence against civilians 29 45 strategic developments 10 0 total 170 440 This table is based on data from the Armed Conflict Location & Event Data Project (datasets used: ACLED, January 2017). This graph is based on data from the Armed Conflict Location & Event Data Project (datasets used: ACLED, January 2017). EGYPT, FOURTH QUARTER 2016: UPDATE ON INCIDENTS ACCORDING TO THE ARMED CONFLICT LOCATION & EVENT DATA PROJECT (ACLED) COMPILED BY ACCORD, 8 FEBRUARY 2017 LOCALIZATION OF CONFLICT INCIDENTS Note: The following list is an overview of the incident data included in the ACLED dataset. More details are available in the actual dataset (date, location data, event type, involved actors, information sources, etc.). In the following list, the names of event locations are taken from ACLED, while the administrative region names are taken from GADM data which serves as the basis for the map above. In Ad Daqahliyah, 1 incident killing 0 people was reported. The following location was affected: Al Mansurah.