Active Inference, Curiosity and Insight

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter Navigation Strategy for the Exomars Schiaparelli EDM Lander Mission

Jet Propulsion Laboratory California Institute of Technology Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter Navigation Strategy for the ExoMars Schiaparelli EDM Lander Mission Premkumar R. Menon Sean V. Wagner, David C. Jefferson, Eric J. Graat, Kyong J. Lee, and William B. Schulze AAS/AIAA Astrodynamics Specialist Conference San Antonio, Texas February 5–9, 2017 AAS Paper 17-337 © 2017 California Institute of Technology. Government Sponsorship Acknowledged. Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter Project Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter (Mission, Spacecraft and PSO) The Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter mission launched in August 2005 from the Cape Canaveral Air Force Station arriving at Mars in March 2006 started science operations in November 2006. MRO has completed 10 years since launch (50,000 orbits by Mar 2017) and to date has returned nearly 300 Terabytes of data. MRO Primary Science Orbit (PSO): • Sun-synchronous orbit ascending node at 3:00 PM ± 15 minutes Local Mean Solar Time (LMST) (daylight equatorial crossing) • Periapsis is frozen about the Mars South Pole • Near-repeat ground track walk (GTW) every 17-day, 211 orbit (short-term repeat) MRO targeting cycle, exact repeat after 4602 orbits. The nominal GTW is 32.45811 km West each 211 orbit cycle (maintained with periodic maneuvers). MRO Spacecraft: • Spacecraft Bus: 3-axis stabilized ACS system; 3-meter diameter High Gain Antenna; hydrazine propulsion system • Instrument Suite: HiRISE Camera, CRISM Imaging spectrometer, Mars Climate Sounder, Mars Color Imager, Context Camera, Shallow Subsurface Radar, Electra engineering payload (among other instrument payloads) 2/07/17 MRO support of ExoMars Schiaparelli Lander Overflight Relay PRM-3 4. MRO shall have good overflight pass geometry within the first 2 Sols after landing. -

Exomars Schiaparelli Direct-To-Earth Observation Using GMRT

TECHNICAL ExoMars Schiaparelli Direct-to-Earth Observation REPORTS: METHODS 10.1029/2018RS006707 using GMRT S. Esterhuizen1, S. W. Asmar1 ,K.De2, Y. Gupta3, S. N. Katore3, and B. Ajithkumar3 Key Point: • During ExoMars Landing, GMRT 1Jet Propulsion Laboratory, California Institute of Technology, Pasadena, CA, USA, 2Cahill Center for Astrophysics, observed UHF transmissions and California Institute of Technology, Pasadena, CA, USA, 3National Centre for Radio Astrophysics, Pune, India Doppler shift used to identify key events as only real-time aliveness indicator Abstract During the ExoMars Schiaparelli separation event on 16 October 2016 and Entry, Descent, and Landing (EDL) events 3 days later, the Giant Metrewave Radio Telescope (GMRT) near Pune, India, Correspondence to: S. W. Asmar, was used to directly observe UHF transmissions from the Schiaparelli lander as they arrive at Earth. The [email protected] Doppler shift of the carrier frequency was measured and used as a diagnostic to identify key events during EDL. This signal detection at GMRT was the only real-time aliveness indicator to European Space Agency Citation: mission operations during the critical EDL stage of the mission. Esterhuizen, S., Asmar, S. W., De, K., Gupta, Y., Katore, S. N., & Plain Language Summary When planetary missions, such as landers on the surface of Mars, Ajithkumar, B. (2019). ExoMars undergo critical and risky events, communications to ground controllers is very important as close to real Schiaparelli Direct-to-Earth observation using GMRT. time as possible. The Schiaparelli spacecraft attempted landing in 2016 was supported in an innovative way. Radio Science, 54, 314–325. A large radio telescope on Earth was able to eavesdrop on information being sent from the lander to other https://doi.org/10.1029/2018RS006707 spacecraft in orbit around Mars. -

Mars 2020 Radiological Contingency Planning

National Aeronautics and Space Administration Mars 2020 Radiological Contingency Planning NASA plans to launch the Mars 2020 rover, produce the rover’s onboard power and to Perseverance, in summer 2020 on a mission warm its internal systems during the frigid to seek signs of habitable conditions in Mars’ Martian night. ancient past and search for signs of past microbial life. The mission will lift off from Cape NASA prepares contingency response plans Canaveral Air Force Station in Florida aboard a for every launch that it conducts. Ensuring the United Launch Alliance Atlas V launch vehicle safety of launch-site workers and the public in between mid-July and August 2020. the communities surrounding the launch area is the primary consideration in this planning. The Mars 2020 rover design is based on NASA’s Curiosity rover, which landed on Mars in 2012 This contingency planning task takes on an and greatly increased our knowledge of the added dimension when the payload being Red Planet. The Mars 2020 rover is equipped launched into space contains nuclear material. to study its landing site in detail and collect and The primary goal of radiological contingency store the most promising samples of rock and planning is to enable an efficient response in soil on the surface of Mars. the event of an accident. This planning is based on the fundamental principles of advance The system that provides electrical power for preparation (including rehearsals of simulated Mars 2020 and its scientific equipment is the launch accident responses), the timely availability same as for the Curiosity rover: a Multi- of technically accurate and reliable information, Mission Radioisotope Thermoelectric Generator and prompt external communication with the (MMRTG). -

Mars Science Laboratory: Curiosity Rover Curiosity’S Mission: Was Mars Ever Habitable? Acquires Rock, Soil, and Air Samples for Onboard Analysis

National Aeronautics and Space Administration Mars Science Laboratory: Curiosity Rover www.nasa.gov Curiosity’s Mission: Was Mars Ever Habitable? acquires rock, soil, and air samples for onboard analysis. Quick Facts Curiosity is about the size of a small car and about as Part of NASA’s Mars Science Laboratory mission, Launch — Nov. 26, 2011 from Cape Canaveral, tall as a basketball player. Its large size allows the rover Curiosity is the largest and most capable rover ever Florida, on an Atlas V-541 to carry an advanced kit of 10 science instruments. sent to Mars. Curiosity’s mission is to answer the Arrival — Aug. 6, 2012 (UTC) Among Curiosity’s tools are 17 cameras, a laser to question: did Mars ever have the right environmental Prime Mission — One Mars year, or about 687 Earth zap rocks, and a drill to collect rock samples. These all conditions to support small life forms called microbes? days (~98 weeks) help in the hunt for special rocks that formed in water Taking the next steps to understand Mars as a possible and/or have signs of organics. The rover also has Main Objectives place for life, Curiosity builds on an earlier “follow the three communications antennas. • Search for organics and determine if this area of Mars was water” strategy that guided Mars missions in NASA’s ever habitable for microbial life Mars Exploration Program. Besides looking for signs of • Characterize the chemical and mineral composition of Ultra-High-Frequency wet climate conditions and for rocks and minerals that ChemCam Antenna rocks and soil formed in water, Curiosity also seeks signs of carbon- Mastcam MMRTG • Study the role of water and changes in the Martian climate over time based molecules called organics. -

Exploration of Mars by the European Space Agency 1

Exploration of Mars by the European Space Agency Alejandro Cardesín ESA Science Operations Mars Express, ExoMars 2016 IAC Winter School, November 20161 Credit: MEX/HRSC History of Missions to Mars Mars Exploration nowadays… 2000‐2010 2011 2013/14 2016 2018 2020 future … Mars Express MAVEN (ESA) TGO Future ESA (ESA- Studies… RUSSIA) Odyssey MRO Mars Phobos- Sample Grunt Return? (RUSSIA) MOM Schiaparelli ExoMars 2020 Phoenix (ESA-RUSSIA) Opportunity MSL Curiosity Mars Insight 2020 Spirit The data/information contained herein has been reviewed and approved for release by JPL Export Administration on the basis that this document contains no export‐controlled information. Mars Express 2003-2016 … First European Mission to orbit another Planet! First mission of the “Rosetta family” Up and running since 2003 Credit: MEX/HRSC First European Mission to orbit another Planet First European attempt to land on another Planet Original mission concept Credit: MEX/HRSC December 2003: Mars Express Lander Release and Orbit Insertion Collission trajectory Bye bye Beagle 2! Last picture Lander after release, release taken by VMC camera Insertion 19/12/2003 8:33 trajectory Credit: MEX/HRSC Beagle 2 was found in January 2015 ! Only 6km away from landing site OK Open petals indicate soft landing OK Antenna remained covered Lessons learned: comms at all time! Credit: MEX/HRSC Mars Express: so many missions at once Mars Mission Phobos Mission Relay Mission Credit: MEX/HRSC Mars Express science investigations Martian Moons: Phobos & Deimos: Ionosphere, surface, -

Insight Spacecraft Launch for Mission to Interior of Mars

InSight Spacecraft Launch for Mission to Interior of Mars InSight is a robotic scientific explorer to investigate the deep interior of Mars set to launch May 5, 2018. It is scheduled to land on Mars November 26, 2018. It will allow us to better understand the origin of Mars. First Launch of Project Orion Project Orion took its first unmanned mission Exploration flight Test-1 (EFT-1) on December 5, 2014. It made two orbits in four hours before splashing down in the Pacific. The flight tested many subsystems, including its heat shield, electronics and parachutes. Orion will play an important role in NASA's journey to Mars. Orion will eventually carry astronauts to an asteroid and to Mars on the Space Launch System. Mars Rover Curiosity Lands After a nine month trip, Curiosity landed on August 6, 2012. The rover carries the biggest, most advanced suite of instruments for scientific studies ever sent to the martian surface. Curiosity analyzes samples scooped from the soil and drilled from rocks to record of the planet's climate and geology. Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter Begins Mission at Mars NASA's Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter launched from Cape Canaveral August 12. 2005, to find evidence that water persisted on the surface of Mars. The instruments zoom in for photography of the Martian surface, analyze minerals, look for subsurface water, trace how much dust and water are distributed in the atmosphere, and monitor daily global weather. Spirit and Opportunity Land on Mars January 2004, NASA landed two Mars Exploration Rovers, Spirit and Opportunity, on opposite sides of Mars. -

Assimilation of EMM-Hope and Mars Lander Observations Into High-Resolution Mesoscale and Local Models Dr.Roland Young, +97137136143, [email protected]

Assimilation of EMM-Hope and Mars lander observations into high-resolution mesoscale and local models Dr.Roland Young, +97137136143, [email protected] Description In 2021 the Emirates Mars Mission (EMM-Hope) will begin surveying the Martian atmosphere, to characterize its lower atmosphere on global scales, measure its geographic, diurnal and seasonal variability, and study the interactions between the lower and upper atmosphere. In this project, we will investigate Mars' lower atmosphere and boundary layer by assimilating data from EMM's thermal infrared instrument EMIRS and from landers and rovers into high-resolution local simulations created using the LMD Mars Mesoscale/Microscale Model, which can be configured as a mesoscale model (MMM) or as a large eddy simulation (LES). Data assimilation is a critical technique in atmospheric science whereby observations are systematically combined with a numerical model to produce complete atmospheric states closer to either model or observations alone. It has been used on Mars with global, low-resolution models for some time, but not yet with high-resolution regional models where the ground topography is well-resolved. This project will first involve adapting an existing Mars data assimilation scheme for the MMM/LES, covering small regions of the planet at high resolution. EMM's unique orbital geometry will provide periodic blanket coverage of atmospheric parameters such as temperatures and aerosol concentrations. In addition, by the time EMM begins taking data there could be as many as four stations with meteorological instrumentation operating on Mars' surface: NASA's Curiosity rover (landed 2012), NASA's Insight lander (landed 2018), NASA's Mars 2020 rover, and ESA/Roscosmos' ExoMars Kazachok lander (both launch 2020). -

Grammatech NASA Curiosity Case Study

CASE Curiosity’s Software Upgrades Upon landing on Mars, Curiosity under- STUDY went a four-day major update to delete the landing software, and install the Mars Curiosity Rover Searches for Signs of Life surface operations programs designed The most technologically with the Help of GrammaTech’s CodeSonar for roaming the red planet. NASA advanced rover ever built, the designed the mission to be able to Curiosity Rover is a mobile laboratory about the size of a After its eight month journey spanning 352 million miles, NASA’s Mars Curiosi- upgrade the software as needed for small SUV. ty Rover completed a spectacular landing with the help of a giant parachute, a different phases of the mission. Software Curiosity’s 17 cameras, robotic jet-controlled descent vehicle, and a bungee-like apparatus called a “sky upgrades are necessary in part because arm, and suite of specialized Curiosity’s computing power is relatively laboratory-like tools and crane.” Due to the time required for messages to travel from Mars to Earth In developing the coding guidelines, JPL instruments are controlled by low compared with what we’re used to and back, the landing procedure was completely controlled by software. To looked at the types of software related more than 2 million lines of on Earth. However, the RAD750 Power- software. boost the reliability of the software, NASA needed advanced static analysis. anomalies that had been discovered in PC microprocessor built into the rover’s missions during the last few decades and redundant flight computers was chosen came up with a short list of problems because it is virtually impervious to that seem to be common across almost high-energy cosmic rays that would every mission. -

Curiosity on the Move

cover-fin-OCT2012_Layout 1 9/12/12 3:04 PM Page 1 9 AMERICA AEROSPACE October 2012 OCTOBER 2012 Curiosity on the move Declassifying the space race: Part 2 High stakes for human-rating spacecraft A PUBLICATION OF THE AMERICAN INSTITUTE OF AERONAUTICS AND ASTRONAUTICS BEATlayout1012_Layout 1 9/11/12 3:24 PM Page 2 ESA to break new ground with ExoMars ESA GOVERNMENT MINISTERS ARE DUE According to ESA, “Final agree- With ESA now committed to develop- to meet in late November to decide on ments to be developed with Russia in ing the rover by itself—the first time it the future of the ExoMars program, a the coming months and final program will have built a robotic rover—the bill two-mission project to search for evi- configuration will be submitted to the for the mission is climbing. In June dence of life on Mars. The first mis- ESA Council Meeting at Ministerial ESA announced a tranche of funds to sion, due for launch in 2016, com- level in November to approve. Av- support the program until the end of prises a trace-gas-sensing orbiter and the year, and the project enjoys the an entry, descent, and landing political support of the key European demonstrator module (EDM), to space organizations—particu- be followed in 2018 with a larly the Italian Space robotic rover equipped Agency, which has a to drill beneath the managing role. The planet’s surface. initial successes ExoMars Mission 2018 Finding of the NASA support Curiosity Mars The project has rover program had a complex fi- have also helped as nancial history. -

Heliophysics 2050 Workshop White Paper 1 Space Weather

Heliophysics 2050 White Papers (2021Heliophysics) 2050 Workshop White Paper 4010.pdf Space Weather Observations and Modeling in Support of Human Exploration of Mars J. L. Green1, C. Dong2, M. Hesse3, C. A. Young4 1NASA Headquarters; 2Princeton University; 3NASA ARC; 4NASA GSFC Abstract: Space Weather (SW) observations and modeling at Mars have begun but it must be significantly increased in order to support the future of Human Exploration. A comprehensive SW understanding at a planet without a global magnetosphere but thin atmosphere is very different than our situation at Earth so there is substantial fundamental research remaining. The next Heliophysics decadal must include a New Initiative in order to meet expected demands for SW information at Mars. Background: The Heliophysics discipline is the “study of the nature of the Sun, and how it influences the very nature of space and, in turn, the atmospheres of planets [NASA website].” Due to the thin atmosphere and maintaining only an induced magnetosphere, Space Weather (SW) effects extend all the way to the surface of Mars. Understanding the SW at Mars is already in progress. Starting with Mars Global Surveyor, a new set of particle and field instruments have been or will soon arrive at Mars on a variety of international missions (see Table 1). Table 1: Past, Current & Near-term Mars Missions Mission Type Key Instrument Key Discoveries Mars Global Orbiter Magnetometer Measured significant remnant field or mini-bubble Surveyor magnetospheres emanating from the surface Mars Express Orbiter -

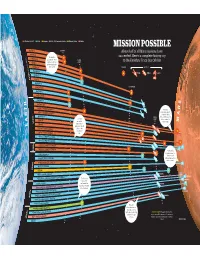

MISSION POSSIBLE KORABL 4 LAUNCH About Half of All Mars Missions Have

Russia/U.S.S.R. U.S. Japan U.K./ESA member states Russia/China India MISSION POSSIBLE KORABL 4 LAUNCH About half of all Mars missions have KORABL 5 ) The frst U.S. succeeded. Here’s a complete history, up s KORAB e L 11 to Mars t spacecraft EARTH a to the ExoMars Trace Gas Orbiter d mysteriously lost ORBIT MARS 1 h power eight hours c n KORA after launch u BL 13 FAILURE SUCCESS a L ( MARINER 3 s Flyby Orbiter Lander 0 MA 6 RINER 4 9 1 ZOND 2 MARINER 6 IN TRANSIT MARS 1969A MARINER 7 MARS 1969B MARINER 8 S H KOSMOS 419 MA R T RS 2 ORBITER/LANDER The frst man-made object MARS 3 ORBITER/LAN DER A R to land on Mars. s MARINER 9 MARS But contact was lost 0 The frst 7 ORBIT 20 seconds after A MARS 9 4 successful touchdown M 1 Mars surface MARS 5 E exploration found all elements MARS 6 FLYBY/LAND ER essential to MARS 7 FLYBY/LANDER life VIKING 1 ORBITER/LANDER VIKING 2 ORBITER/LANDER s 0 PHOBOS 1 ORBITER/LANDER 8 9 PHOBOS 2 ORBITER/LANDER 1 Pathfinder’s Sojourner was the MARS OBSERVER frst wheeled MARS GLOBAL SURVEYOR vehicle deployed on another planet s MARS 96 ORBITER/LANDER 0 9 MARS PATHFINDER 9 1 NOZOMI MARS CLIMATE ORBITER ONGOING ONGOING 2 PROBES/MARS POLAR LANDER The Phoenix ONGOING DEEP SPACE ONGOING lander frst MARS ODYSSEY confrmed the ONGOING presence of water /BEAGLE 2 LANDER MARS EXPRESS ORBITER in soil samples s RIT MARS EXPLORATION ROVER–SPI ONGOING 0 0 OVER–OPPORTUNITY 0 MARS EXPLORATION R ONGOING 2 ITER MARS RECONNAISSANCE ORB ENIX MARS LANDER PHO Curiosity descended on the -GRUNT/YINGHUO-1 PHOBOS frst “sky crane,” a s B/CURIOSITY highly precise landing DID YOU KNOW? The early missions had 0 MARS SCIENCE LA 1 system for large up to seven diferent names. -

Dynamical Meteorology of the Martian Atmosphere

Aspects of Martian Meteorology From SurfaceDynamical Observations Meteorology Including of from the the Martian2012 Mars Atmosphere “Curiosity” Rover Mars Science Laboratory Curiosity The “Curiosity” rover in clean room at JPL Mars Science Laboratory Curiosity Mars Science Laboratory Curiosity Mars Science Laboratory Curiosity Outline • Basics – orbit, topography, atmospheric composition • Basics – dust, dust everywhere • History of Mars planetary missions 1962-today • Satellite measurments of atmospheric temperature • Surface T, P and u,v observations • Pressure record – annual cycle, baroclinic waves • Pressure record – diurnal variations (atmospheric tides) • Mars General Circulation Models (GCMs) • Model simulations of atmospheric tides • I am curious about Curiosity! Mars orbit and annual cycle • Measure time through the year (or position through the o orbit) by Ls (“Areocentric longitude”) (defined so that Ls=0 is NH spring equinox “March 21”) • Aphelion 249,209,300 km • Perihelion 206,669,000 km o • Ls of perihelion 250 - late SH spring Mars orbit and annual cycle • Measure time through the year (or position through the o orbit) by Ls (“Areocentric longitude”) (defined so that Ls=0 is NH spring equinox “March 21”) 2 2 Ra /Rp = 1.42 (vs. 1.07 for Earth) • Aphelion 249,209,300 km • Perihelion 206,669,000 km o • Ls of perihelion 250 - late SH spring CO2 Ice Cap Helas Basin Tharsus Rise Helas Basin Equatorial section through smoothed topography Equatorial section through smoothed topography Zonal wavenumber 2 topography • 1962 Mars