Partnership Bridge

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Introducion to Duplicate

INTRODUCTION to DUPLICATE INTRODUCTION TO DUPLICATE BRIDGE This book is not about how to bid, declare or defend a hand of bridge. It assumes you know how to do that or are learning how to do those things elsewhere. It is your guide to playing Duplicate Bridge, which is how organized, competitive bridge is played all over the World. It explains all the Laws of Duplicate and the process of entering into Club games or Tournaments, the Convention Card, the protocols and rules of player conduct; the paraphernalia and terminology of duplicate. In short, it’s about the context in which duplicate bridge is played. To become an accomplished duplicate player, you will need to know everything in this book. But you can start playing duplicate immediately after you read Chapter I and skim through the other Chapters. © ACBL Unit 533, Palm Springs, Ca © ACBL Unit 533, 2018 Pg 1 INTRODUCTION to DUPLICATE This book belongs to Phone Email I joined the ACBL on ____/____ /____ by going to www.ACBL.com and signing up. My ACBL number is __________________ © ACBL Unit 533, 2018 Pg 2 INTRODUCTION to DUPLICATE Not a word of this book is about how to bid, play or defend a bridge hand. It assumes you have some bridge skills and an interest in enlarging your bridge experience by joining the world of organized bridge competition. It’s called Duplicate Bridge. It’s the difference between a casual Saturday morning round of golf or set of tennis and playing in your Club or State championships. As in golf or tennis, your skills will be tested in competition with others more or less skilled than you; this book is about the settings in which duplicate happens. -

Things You Might Like to Know About Duplicate Bridge

♠♥♦♣ THINGS YOU MIGHT LIKE TO KNOW ABOUT DUPLICATE BRIDGE Prepared by MayHem Published by the UNIT 241 Board of Directors ♠♥♦♣ Welcome to Duplicate Bridge and the ACBL This booklet has been designed to serve as a reference tool for miscellaneous information about duplicate bridge and its governing organization, the ACBL. It is intended for the newer or less than seasoned duplicate bridge players. Most of these things that follow, while not perfectly obvious to new players, are old hat to experienced tournaments players. Table of Contents Part 1. Expected In-behavior (or things you need to know).........................3 Part 2. Alerts and Announcements (learn to live with them....we have!)................................................4 Part 3. Types of Regular Events a. Stratified Games (Pairs and Teams)..............................................12 b. IMP Pairs (Pairs)...........................................................................13 c. Bracketed KO’s (Teams)...............................................................15 d. Swiss Teams and BAM Teams (Teams).......................................16 e. Continuous Pairs (Side Games)......................................................17 f. Strategy: IMPs vs Matchpoints......................................................18 Part 4. Special ACBL-Wide Events (they cost more!)................................20 Part 5. Glossary of Terms (from the ACBL website)..................................25 Part 6. FAQ (with answers hopefully).........................................................40 Copyright © 2004 MayHem 2 Part 1. Expected In-Behavior Just as all kinds of competitive-type endeavors have their expected in- behavior, so does duplicate bridge. One important thing to keep in mind is that this is a competitive adventure.....as opposed to the social outing that you may be used to at your rubber bridge games. Now that is not to say that you can=t be sociable at the duplicate table. Of course you can.....and should.....just don=t carry it to extreme by talking during the auction or play. -

Bernard Magee's Acol Bidding Quiz

Number: 178 UK £3.95 Europe €5.00 October 2017 Bernard Magee’s Acol Bidding Quiz This month we are dealing with hands when, if you choose to pass, the auction will end. You are West in BRIDGEthe auctions below, playing ‘Standard Acol’ with a weak no-trump (12-14 points) and four-card majors. 1. Dealer North. Love All. 4. Dealer West. Love All. 7. Dealer North. Love All. 10. Dealer East. E/W Game. ♠ 2 ♠ A K 3 ♠ A J 10 6 5 ♠ 4 2 ♥ A K 8 7 N ♥ A 8 7 6 N ♥ 10 9 8 4 3 N ♥ K Q 3 N W E W E W E W E ♦ J 9 8 6 5 ♦ A J 2 ♦ Void ♦ 7 6 5 S S S S ♣ Q J 3 ♣ Q J 6 ♣ A 7 4 ♣ K Q J 6 5 West North East South West North East South West North East South West North East South Pass Pass Pass 1♥ 1♠ Pass Pass 1♣ 2♦1 Pass 1♥ 1♠ ? ? Pass Dbl Pass Pass 2♣ 2♠ 3♥ 3♠ ? 4♥ 4♠ Pass Pass 1Weak jump overcall ? 2. Dealer North. Love All. 5. Dealer West. Love All. 8. Dealer East. Love All. 11. Dealer North. N/S Game. ♠ 2 ♠ A K 7 6 5 ♠ A 7 6 5 4 3 ♠ 4 3 2 ♥ A J N ♥ 4 N ♥ A K 3 N ♥ A 7 6 N W E W E W E W E ♦ 8 7 2 ♦ A K 3 ♦ 2 ♦ A 8 7 6 4 S S S S ♣ K Q J 10 5 4 3 ♣ J 10 8 2 ♣ A 5 2 ♣ 7 6 West North East South West North East South West North East South West North East South Pass Pass Pass 1♠ 2♥ Pass Pass 3♦ Pass 1♣ 3♥ Dbl ? ? Pass 3♥ Pass Pass 4♥ 4♠ Pass Pass ? ? 3. -

Hall of Fame Takes Five

Friday, July 24, 2009 Volume 81, Number 1 Daily Bulletin Washington, DC 81st Summer North American Bridge Championships Editors: Brent Manley and Paul Linxwiler Hall of Fame takes five Hall of Fame inductee Mark Lair, center, with Mike Passell, left, and Eddie Wold. Sportsman of the Year Peter Boyd with longtime (right) Aileen Osofsky and her son, Alan. partner Steve Robinson. If standing ovations could be converted to masterpoints, three of the five inductees at the Defenders out in top GNT flight Bridge Hall of Fame dinner on Thursday evening The District 14 team captained by Bob sixth, Bill Kent, is from Iowa. would be instant contenders for the Barry Crane Top Balderson, holding a 1-IMP lead against the They knocked out the District 9 squad 500. defending champions with 16 deals to play, won captained by Warren Spector (David Berkowitz, Time after time, members of the audience were the fourth quarter 50-9 to advance to the round of Larry Cohen, Mike Becker, Jeff Meckstroth and on their feet, applauding a sterling new class for the eight in the Grand National Teams Championship Eric Rodwell). The team was seeking a third ACBL Hall of Fame. Enjoying the accolades were: Flight. straight win in the event. • Mark Lair, many-time North American champion Five of the six team members are from All four flights of the GNT – including Flights and one of ACBL’s top players. Minnesota – Bob and Cynthia Balderson, Peggy A, B and C – will play the round of eight today. • Aileen Osofsky, ACBL Goodwill chair for nearly Kaplan, Carol Miner and Paul Meerschaert. -

Kibitzerkibitzer December, 2007

Palo Alto Unit 503 Volume XLV, Issue 12 KibitzerKibitzer December, 2007 Bridge, Dinner, and a Toy UNIT INFORMATION MISUSED SUNDAY, DECEMBER 9 Recently some of our members’ personal information provided by the ACBL was used to solicit them for com- Celebrate the Season by grabbing your favorite part- mercial purposes. The Unit respects our members' privacy and wants our members to know that the Unit as well as ner, finding a toy, and signing up to play free bridge and the ACBL does not permit this and that we are taking ac- eat a free dinner catered by Chef Chu on Sunday, Decem- tion to prevent this from recurring. ber 9th at your friendly Bridge Center. Your only pay- ment is in the form of an unwrapped new toy. The Unit has a new charity “Toys for Kids,” a local program for GIFTS GALORE needy kids in the Palo Alto area. They are looking for toys and games for children from pre-school to around GREET STAC PLAYERS sixth grade. Gift certificates for food (especially fast food) are popular with the older children. Partnerships should sign up before December 3. The Talk about the holiday spirit! Your friendly local Unit regrets that there is room for only 70 partnerships; club will award presents of extra masterpoints to those both must be Unit members. There will be two flights, an who excel in the STAC (Sectional Tournament at Clubs) open and a 99er. After the December 3 deadline the Tour- games during the week of Monday, December 17 through nament Chair, Martie Moore, will review the sign-up list Sunday, December 23. -

Skill Preferred, but Luck Is More Than Welcome Strul Takes Slim Lead In

Saturay, December 1, 2007 Volume 80, Number 9 Daily Bulletin 80th Fall North American Bridge Championships Editors: Brent Manley and Paul Linxwiler Skill preferred, but luck Strul takes slim is more than welcome lead in Reisinger Many years ago, Allan Falk was playing in the Vanderbilt The team captained by Aubrey Strul, winners of the Mitchell Board-a-Match Knockout Teams. At one point early in the event, Falk and Teams earlier in the tournament, hold a narrow lead going into today’s semifinal his teammates found themselves pitted against a squad that sessions of the Reisinger Board-a-Match Teams. included some of the continent’s best players. Strul, a Floridian, is playing with Michael Becker, Larry Cohen, David Falk remembers the occasion so well because the Berkowitz, Chip Martel and Lew Stansby. heavily favored team bid five slams that rated to make After two qualifying sessions, they were one board clear of the Russian- better than two-thirds of the time – and each went down on a Polish foursome of Andrew Gromov – Aleksander Dubinin and Cezary Balicki – foul trump split, and each was a loss for the stars. Falk and Adam Zmudzinski. company surprised even themselves by advancing in the The field will be reduced to 14 teams for the two final sessions on Sunday. Vanderbilt. It doesn’t take much analytical skill to conclude that the major factor in the win by Falk’s team was good, old-fashioned luck. They were in the right place at Austrians leading the right time. Falk does note, by the way, that his team was good enough to win two more matches after their big upset. -

Gateway to the West Regional Sunday

Sunday July 14-19 Hi 92°F Low 75°F Daily Bulletin Gateway to the West Regional All St. Louis Regional Results: for coming to St. Louis and we’d like www.acbl.org & www.unit143.org, to see you right back here again next Unit 143 includes links to the week’s Daily Bulletins. year. We appreciate that you chose to attend our Regional ’coz we do it all for you! to our Caddies, We appreciate your fine work this week! Jackson Florea Anna Garcia Jenna Percich Lauren Percich Clara Riggio Frank Riggio Katie Seibert Kate Vontz Our Date Back to August 15-21, 2016 Come back and join us next August. Please put us on your Regional tournament calendar today. Charity Pairs Series Raises $ BackStoppers will receive the $$$$ that you helped us raise in the Saturday morning Charity Open Pairs Game and will be added to what Last Chance for Registration Gift & was raised in the Wednesday evening Swiss event. We support this To Pick Up Your Section Top Awards organization to express our appreciation for lives given on behalf of Sunday, from 10:00 – 10:20 AM before the Swiss Team session others. Unit 143 will present the check at their October Sectional. begins, and 30 minutes after the sessions end, will be the last opportunity to pick up your convention card holder and section Thanks for playing in these events and showing your support! top awards. Daily Grin How can you tell if someone is a lousy bridge player? No Peeking, Lew! He has 5 smiling Kibitzers watching him play. -

Rivista N. 07-08.1988

CAMPIONATO ITALIANO COPPIE MISTE 1998 CHIUSURA ISCRIZIONI PER TUTTI I PARTECIPANTI ALLA FASE LOCALE/REGIONALE: 25 settembre 1998 PER LE COPPIE AVENTI DIRITTO ALLA FASE DI FINALE NAZIONALE: 25 settembre 1998 QUOTE ISCRIZIONE e PRESTITI La quota iscrizione per le coppie partecipanti alla fase locale/regionale è di lire 120.000 da inviare ai Comitati Regionali di competenza. Gli eventuali prestiti delle coppie iscritte alla fase locale/provinciale sono classificati come prestiti regionali (lire 50.000) se effettuati tra Società della stessa Regione, diventano invece Prestiti Nazionali se effettuati tra Società di diversa Regione. Le coppie promosse dalla fase locale/regionale alla fase Finale Nazionale integreranno la loro iscrizione (lire 80.000) direttamente a SALSOMAGGIORE TERME il giorno 30 ottobre 1998 al momento della conferma della partecipazione. La quota iscrizione per le coppie aventi diritto alla fase di Finale Nazionale è di lire 200.000 da inviare assieme agli elenchi delle formazioni alla segreteria FIGB - via C. Menotti 11/C-20129 MILANO (Sez. Campionati e Tornei) entro la data di chiusura delle iscrizioni. Le coppie non confermate entro il 25 settembre 1998 perderanno il diritto alla partecipazione alla fase Finale Nazionale. Gli eventuali prestiti delle coppie aventi diritto alla fase di Finale Nazionale sono Prestiti Nazionali. DATE DI SVOLGIMENTO Fase Locale/Regionale: a cura dei Comitati Regionali, entro il 25 ottobre 1998. Fase Finale Nazionale: Salsomaggiore Terme dal 30 ottobre all’1 novembre 1998. ELENCHI DELLE COPPIE -

2000 Bridge Bulletin Index

2000 Bridge Bulletin Index ACBL BRIDGE HALL OF FAME. George Rosenkranz named Blackwood Award winner, Meyer Schleifer receives the von Zedtwitz Award C February. Hall of Fame inducts Lou Bluhm, Harry Fishbein, Charles Solomon, George Rosenkranz, Sidney Lazard, Meyer Schleifer and Ira Rubin C October. ACBL BOARD OF DIRECTORS. Highlights from the Boston Board meeting --- February. Election notice C March C May . Highlights of Cincinnati Board meeting C May. Highlights from the Anaheim meeting C October. Election results for 2000 Board C November. ACBL CHARITY FOUNDATION. 2000 Charity Committee appointees named --- February. ACBL CHARITY GAME. Winners C August. ACBL GOODWILL COMMITTEE. 2000 Appointees named --- February. ACBL HALL OF FAME. Rosenkranz wins Blackwood award; Meyer Schleifer is von Zedtwitz award winner C February. ACBL HONORARY MEMBER OF THE YEAR. Chip Martel named for 2000 --- February. ACBL INSTANT MATCHPOINT GAME. Promo C August, September. Results C December. ACBL INTERNATIONAL FUND GAME. Winners C July, November. ACBL PATRON MEMBER LIST. December. ACBL SENIOR GAME. Winners C May. ACE OF CLUBS. Winners of the 1999 contest --- April. AMERICAN BRIDGE ASSOCIATION. Schedule of upcoming national events --- monthly. ANAHEIM NABC. Promos C April --- July. Meltzer squad wins Spingold; Wei-Sender team takes Wagar; District 9 repeats win in GNT-A; District 19 wins GNT-B title; District 13 victorious in GNT-C contest; Zia, Rosenberg top LM Pairs field; Ping, Leung win Red Ribbon; Nugit squad wins Senior Swiss teams C October. Willenken, Silverstein win Fast Open Pairs; Bach and Burgess take IMP Pairs title; Mixed B-A-M winners; 199er Pairs winners; Five-way tie fir Fishbein Trophy; other NABC highlights C November. -

This Month's Newsletter Includes the Sections Listed Below. Click a Link to Jump to the Corresponding Section

This month's newsletter includes the sections listed below. Click a link to jump to the corresponding section. If your browser does not support these links, scroll down to find a specific section. ♦ President's Message ♦ Board Business ♦ New Members and Rank Advancements ♦ Unit News ♦ Club News ♦ From the Editors Please visit the Unit 174 Website (www.acblunit174.org) to view updated information about the activities in our Unit and at our Clubs. Wow – The 2019 Lone Star Regional is in the books – what a great week of bridge it was!!! I hope everyone had an enjoyable experience and played bridge to their heart's content. Personally, it was hectic, busy, and, looking back, fun and rewarding. It was good to see everyone from all over our Unit and District. Thank you to all who came and played! I would like to thank many people for all their efforts leading up to and during the week. My first thank you is to Lauri Laufman for her tireless work in planning, creating the schedule, working with the Marriott staff, updating the Daily Bulletin and being a sounding board and outstanding bridge partner! Lauri worked very hard to ensure this LSR was the best ever and I thank her for all her efforts. My thanks to the Unit Board – you all are supportive and willing to do whatever it takes to make sure the needs of the players are met. I would also like to thank our Chairpersons of the Hospitality, I/N and Newcomers and Partnership desks – Sam Khayatt, Nancy Guthrie and Bill and Nancy Riley. -

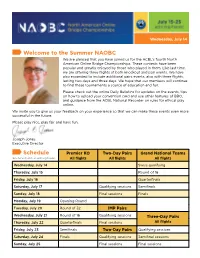

Schedule Welcome to the Summer NAOBC

Wednesday, July 14 Welcome to the Summer NAOBC We are pleased that you have joined us for the ACBL’s fourth North American Online Bridge Championships. These contests have been popular and greatly enjoyed by those who played in them. Like last time, we are offering three flights of both knockout and pair events. We have also expanded to include additional pairs events, also with three flights, lasting two days and three days. We hope that our members will continue to find these tournaments a source of education and fun. Please check out the online Daily Bulletins for updates on the events, tips on how to upload your convention card and use other features of BBO, and guidance from the ACBL National Recorder on rules for ethical play online. We invite you to give us your feedback on your experience so that we can make these events even more successful in the future. Please play nice, play fair and have fun. Joseph Jones Executive Director Schedule Premier KO Two-Day Pairs Grand National Teams See full schedule at acbl.org/naobc. All flights All flights All flights Wednesday, July 14 Swiss qualifying Thursday, July 15 Round of 16 Friday, July 16 Quarterfinals Saturday, July 17 Qualifying sessions Semifinals Sunday, July 18 Final sessions Finals Monday, July 19 Opening Round Tuesday, July 20 Round of 32 IMP Pairs Wednesday, July 21 Round of 16 Qualifying sessions Three-Day Pairs Thursday, July 22 Quarterfinals Final sessions All flights Friday, July 23 Semifinals Two-Day Pairs Qualifying sessions Saturday, July 24 Finals Qualifying sessions Semifinal sessions Sunday, July 25 Final sessions Final sessions About the Grand National Teams, Championship and Flight A The Grand National Teams is a North American Morehead was a member of the National Laws contest with all 25 ACBL districts participating. -

VI. Slam-Bidding Methods

this page intentionally left blank We-Bad System Document January 16, 2011 “We-Bad”: Contents IV. Competitive-Bidding Methods page numbers apply to PDF only A. Competition After Our Preempt 32 B. Competition After Our Two-Club Opening 32 Introduction 4 C. Competition After Our One-Notrump Opening 33 I. Definitions 5 D. Competition After Our Major-Suit Opening 34 II. General Understandings and E. Competition After Our Minor-Suit Opening 35 Defaults 6 F. Competition After Any Suit One-Bid 36 III. Partnership-Bidding Methods V. Defensive-Bidding Methods A. Opening-Bid A. Initial Defensive-Action Requirements 39 Requirements 10 A2. All-Context Actions 46 B. Choice of Suit 11 B. After Our Double of a One-Bid 46 C. After Our Preempt 12 C. After Our Suit Overcall of a One-Bid 47 D. After Our Two Clubs 13 D. After Our One-Notrump Overcall 48 E. After Our Two-Notrump- E. After We Reopen a One-Bid 48 Family Opening 14 F. When the Opener has Preempted 48 F. After Our One-Notrump G. After Our Sandwich-Position Action 50 Opening 16 G. Delayed Auction Entry 50 G. After Our Major-Suit VI. Slam-Bidding Methods 51 Opening 20 VII. Defensive Carding 59 H. After Our Minor-Suit VIII. Related Tournament-Ready Systems 65 Opening 25 IX. Other Resources 65 I. After Any Suit One-Bid 26 Bridge World Standard following 65 3 of 65 1/16/2011 9:52 AM 3 of 65 We-Bad System Document Introduction (click for BWS) We-Bad is a scientific 5-card major system very distantly descended from Bridge World Standard.