The Egyptian Velar Fricatives and Their Palatalization

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Helmut Satzinger What Happened to the Voiced Consonants of Egyptian?

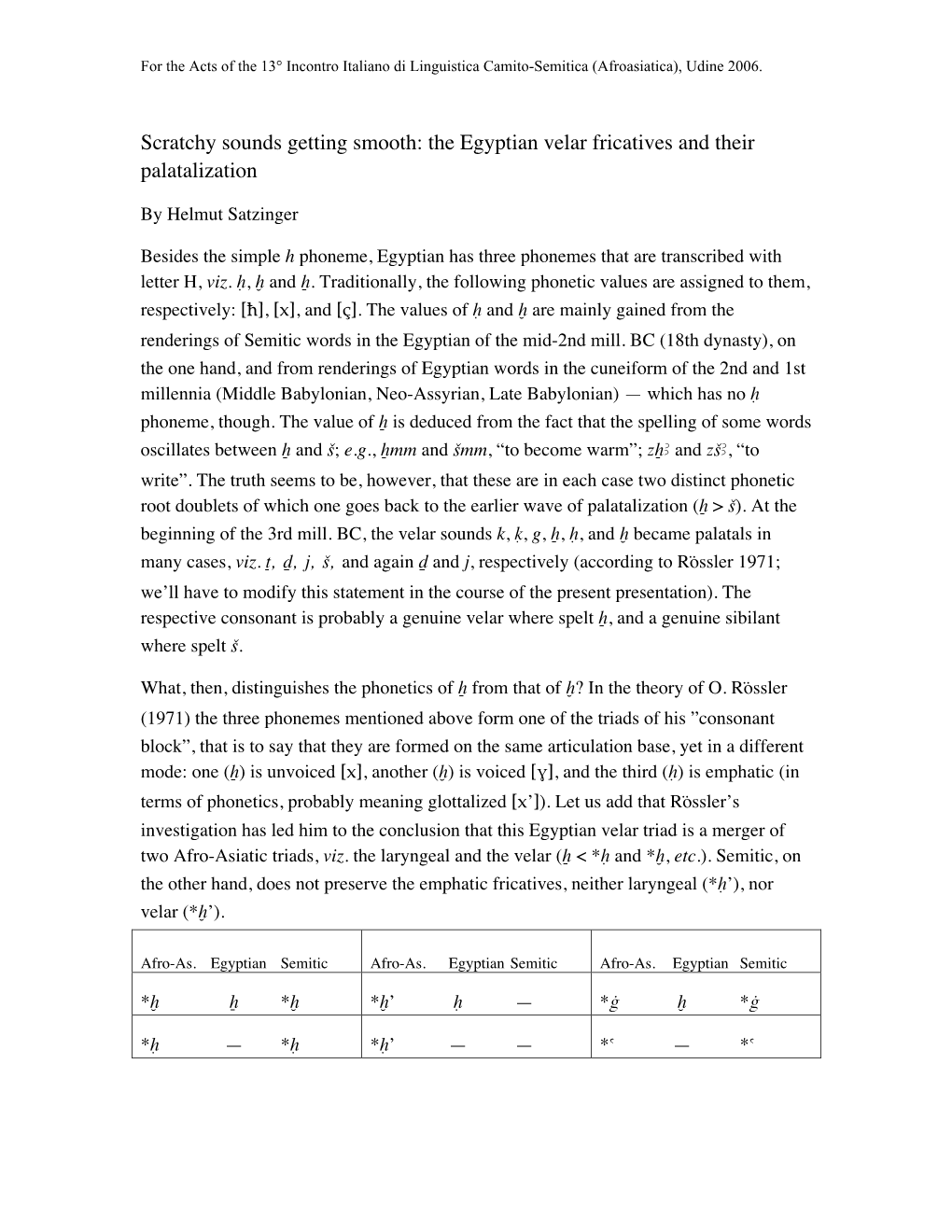

Helmut Satzinger What happened to the voiced consonants of Egyptian!? Coptic has five voiced consonants, viz. the sonorants, b [B], r [r], l [l], m [m], and n [n]. Otherwise, Coptic has no voiced consonants: neither stops, nor fricatives (W. H. WORRELL, Coptic Sounds. University of Michigan Studies Humanistic Series XXVI (Ann Arbor, 1934), 17-23 et passim). Delta Coptic (Bohairic): Stops and fricatives are found at four points of articulation: labial, alveolar, prepalatal, and velar. The stops are of two modes of articulation: 1) voiceless, aspirated, fortis; 2) voiceless, unaspirated, lenis. Labials: f [ph] p [b]8 w [!] Alveolars: u [th] t [d8] s [s] h Prepalatals: q [c ] è [Ô8] é [S] h Velars: x [k ] k [g8] ; [x] — — à [h] Valley Coptic (dialects1 K, F, V, M, N, L, S, P, I, A, etc.): Stops and fricatives are found at five points of articulation: labial, alveolar, prepalatal, palatal, and velar. The stops are of but one mode of articulation: voiceless, unaspirated, lenis. Labial: p [b]8 w [!] Alveolars: t [d8] s [s] Prepalatal è [Ô8] é [S] Palatal q [g8] P µ, I ! [ç] Velar k [g8] A $ [x] (double vowel) [/] à [h] The assumed voiced stops of Egyptian are emphatic, rather than voiced. Is the lack of voiced stops and fricatives a feature only of Coptic, or is it already found in older stages of the language? The transcription of Egyptian creates the impression that it possessed voiced plosives and affricates, viz. b, d, D, and g: 1 Cf. A. S. ATIYA (ed.), The Coptic Encyclopedia (New York 1991), vol. -

University of Southampton

UNIVERSITY OF SOUTHAMPTON Faculty of Physical Sciences and Engineering School of Electronics and Computer Science Modern Standard Arabic Phonetics for Speech Synthesis Nawar Halabi Supervisor: Prof Mike Wald Internal Examiner: Dr Gary B Wills External Examiner: Assoc Prof Nizar Habash Thesis for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy July 2016 i ABSTRACT Arabic phonetics and phonology have not been adequately studied for the purposes of speech synthesis and speech synthesis corpus design. The only sources of knowledge available are either archaic or targeted towards other disciplines such as education. This research conducted a three- stage study. First, Arabic phonology research was reviewed in general, and the results of this review were triangulated with expert opinions – gathered throughout the project – to create a novel formalisation of Arabic phonology for speech synthesis. Secondly, this formalisation was used to create a speech corpus in Modern Standard Arabic and this corpus was used to produce a speech synthesiser. This corpus was the first to be constructed and published for this dialect of Arabic using scientifically-supported phonological formalisms. The corpus was semi-automatically annotated with phoneme boundaries and stress marks; it is word-aligned with the orthographical transcript. The accuracy of these alignments was compared with previous published work, which showed that even slightly less accurate alignments are sufficient for producing high quality synthesis. Finally, objective and subjective evaluations were conducted to assess the quality of this corpus. The objective evaluation showed that the corpus based on the proposed phonological formalism had sufficient phonetic coverage compared with previous work. The subjective evaluation showed that this corpus can be used to produce high quality parametric and unit selection speech synthesisers. -

Reverse Engineering: Emphatic Consonants and the Adaptation of Vowels in French Loanwords Into Moroccan Arabic *

Brill’s Annual of Afroasiatic Languages and Linguistics 1 (2009) 41–74 brill.nl/baall Reverse Engineering: Emphatic Consonants and the Adaptation of Vowels in French Loanwords into Moroccan Arabic * Michael Kenstowicz and Nabila Louriz [email protected] [email protected] Abstract On the basis of two large corpora of French (and Spanish) loanwords into Moroccan Arabic, the paper documents and analyzes the phenomenon noted by Heath (1989) in which a pharyngeal- ized consonant is introduced in the adaptation of words with mid and low vowels such as moquette > [MokeT] = /MukiT/ ‘carpet’. It is found that French back vowels are readily adapted with pharyngealized emphatics while the front vowels tend to resist this correspondence. Th e implications of the phenomenon for general models of loanword adaptation are considered. It is concluded that auditory similarity and salience are critical alternative dimensions of faithfulness that may override correspondences based on phonologically contrastive features. Keywords pharyngealization , enhancement , auditory salience , weighted constraints , harmony 1. Introduction One of the most interesting questions in the theory of loanword adaptation concerns the role of redundant features. It is well known that phonological contrasts on consonants are often correlated with the realization of the same or a related (enhancing) feature on adjacent vowels. Such redundant proper- ties are known to play a role in speech perception and frequently share or take * A preliminary version of this paper was written while the second author was a Fulbright scholar at MIT (spring-summer 2008) and was presented at the Linguistics Colloquium, Paris 8 (November 2008). Th e paper was completed while the fi rst author was Visiting Professor at the Research Institute for Languages and Cultures of Asia and Africa, Tokyo University of Foreign Studies in the winter of 2008-9. -

A Critical and Comparative Study of the Spoken Dialect of Badr and District in Saudi Arabia, M

A CRITICAL AND COMPARATIVE STUDY OF THE SPOKEN DIALECT OF THE NARB TRIBE IN SAUDI ARABIA A thesis presented to the University of Leeds Department of Semitic Studies by ALAYAN. MOHAMMED IL-HAZMY for The Degree of-Doctor of Philosophy April YFr fi xt ?031 This dissertation has never been submitted to this or any other University. PREFACE The aim of this thesis is to describe and study analytically the dialect of the Harb tribe, and to determine its position among the neighbouring tribes. Harb is a very large tribe occupying an extensive area of Saudi Arabia, and it was impracticable for one individual to survey every settlement. This would have occupied a lengthy period, and would best be done by a team of investigators, rather than an individual. Thus we have limited our investigation to-two"-selected'regions, which we believe to be representative, the first ranging from north-east Rabigh up to al-Madina (representing the speech of the Harb in the Hijaz), and the second ranging from al-Madina to al-Fawwara in al-Qasirn district (representing the speech of the Harb in Central Arabia). We have thus left out of consideration an area extending fromCOsfän to Räbigh, where some-. members-of the Harb, partic- ularly those of the Muabbad, Bishr and Zubaid clan live. We have been unable in the northern central region, to go as far as al-Quwära and Dukhnah. However, some Harbis from the unsurveyed area were met with in our regions, and samples of their speech were obtained and included. Within these limitations, however the datä'collected are substantial and it is hoped comprehensive enough to give a clear picture of the main features of the Harb dialect. -

The Impact of the Phonological System of Some European

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Archive Ouverte en Sciences de l'Information et de la Communication The Impact of the Phonological System of some European Languages on Arabic Taoufik Gouma In this article I show one of the important linguistic impacts of some foreign languages on Arabic. Besides the setting up of many linguistic systems such as the second official language of the country, bilingualism, etc. colonialism had also affected the way Arabic countries transcribe Arabic names using the Latin alphabetical system. We are going to show here some of the most important aspects of this impact and also some related problematic issues. The countries concerned with this study are those of the Maghreb; Morocco, Algeria and Tunisia (French Speaking Countries or FSC henceforth) and the countries of the Golf; Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates, including Egypt (English Speaking Countries or ESC henceforth). Keywords: Arabic, phonology, phonetics, colonial languages, name transcription, Latin alphabet. 1 A Brief History about Colonialism in the Arabic Countries. Colonialism is the building and maintaining of colonies in one territory by people from another territory. It is something which has always existed through history, but its reasons are different. People in the first era of existence used to move from one area to another looking for shelter, food, water, etc. Later, by the development of life and its needs, the reasons changed. From the 14th century, powerful countries, such as Spain and England, started to look for other lands in order to acquire more lands, more power and more richness. -

The Writing Revolution

9781405154062_1_pre.qxd 8/8/08 4:42 PM Page iii The Writing Revolution Cuneiform to the Internet Amalia E. Gnanadesikan A John Wiley & Sons, Ltd., Publication 9781405154062_1_pre.qxd 8/8/08 4:42 PM Page iv This edition first published 2009 © 2009 Amalia E. Gnanadesikan Blackwell Publishing was acquired by John Wiley & Sons in February 2007. Blackwell’s publishing program has been merged with Wiley’s global Scientific, Technical, and Medical business to form Wiley-Blackwell. Registered Office John Wiley & Sons Ltd, The Atrium, Southern Gate, Chichester, West Sussex, PO19 8SQ, United Kingdom Editorial Offices 350 Main Street, Malden, MA 02148-5020, USA 9600 Garsington Road, Oxford, OX4 2DQ, UK The Atrium, Southern Gate, Chichester, West Sussex, PO19 8SQ, UK For details of our global editorial offices, for customer services, and for information about how to apply for permission to reuse the copyright material in this book please see our website at www.wiley.com/wiley-blackwell. The right of Amalia E. Gnanadesikan to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, except as permitted by the UK Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988, without the prior permission of the publisher. Wiley also publishes its books in a variety of electronic formats. Some content that appears in print may not be available in electronic books. Designations used by companies to distinguish their products are often claimed as trademarks. -

125-12 Rorient 2-12.Indd

RECENZJE 147 the eldest Solomon’s son, born two or three years after the latter’s accession to the throne at the age of twelve, as stated in III Kings 2:12 and in the Seder Olam Rabba 14, one may date the birth of Solomon ca. 959/8 B.C., about two years after the conquest of Jerusalem by David, if we rely on the historical background hidden behind the account of II Samuel 11:2-12:23 (cf. E. Lipiński, Itineraria Phoenicia, Leuven 2004, pp. 499–500). David’s reign in Jerusalem started then ca. 961/0 B.C. after a longue career of arms in the service of King Saul and of the Philistines, and a shorter reign at Hebron. The unique Iron Age stratum at Khirbet Qeiyafa is certainly somewhat older and must go back to the time of King Saul, as indicated also by the inscription on ostracon, at least if we follow the decipherment and the quite convincing interpretation of É. Puech. The material culture of Khirbet Qeiyafa should then be regarded as belonging to the North-Israelite tribe of Benjamin, a member of which was precisely King Saul. His power centre was Gibea of Benjamin, usually identified with Tell al-Fūl, some 30 km. north-east of Khirbet Qeiyafa. Since the first king of Israel was a Benjaminite, the tribe of Benjamin must have been an important one at that time, with a larger territory than the one attributed to the Benjaminites in later written sources. Moreover, the association of Khirbet Qeiyafa with an intermediate Iron I-II North-Israelite territorial formation is acceptable also from an archaeological view point, as shown by a recent study of I. -

Camsemud 2007

History of the Ancient Near East / Monographs – X —————————————————————— CAMSEMUD 2007 PROCEEDINGS OF THE 13TH ITALIAN MEETING OF AFRO-ASIATIC LINGUISTICS Held in Udine, May 21st!24th, 2007 Edited by FREDERICK MARIO FALES & GIULIA FRANCESCA GRASSI —————————————————————— S.A.R.G.O.N. Editrice e Libreria Padova 2010 HANE / M – Vol. X —————————————————————— History of the Ancient Near East / Monographs Editor-in-Chief: Frederick Mario Fales Editor: Giovanni B. Lanfranchi —————————————————————— ISBN 978-88-95672-05-2 4227-204540 © S.A.R.G.O.N. Editrice e Libreria Via Induno 18B I-35134 Padova [email protected] I edizione: Padova, aprile 2010 Proprietà letteraria riservata Distributed by: Eisenbrauns, Winona Lake, Indiana 46590-0275 USA http://www.eisenbrauns.com Stampa a cura di / Printed by: Centro Copia Stecchini – Via S. Sofia 58 – I-35121, Padova —————————————————————— S.A.R.G.O.N. Editrice e Libreria Padova 2010 TABLE OF CONTENTS F.M. Fales – G.F. Grassi, Foreword ............................................................................. v I. SAILING FROM THE ADRIATIC TO ASIA/AFRICA AND BACK G.F. Grassi, Semitic Onomastics in Roman Aquileia ............................................... 1 F. Aspesi, A margine del sostrato linguistico “labirintico” egeo-cananaico ....... 33 F. Israel, Alpha, beta … tra storia–archeologia e fonetica, tra sintassi ed epigrafia ...................................................................................................... 39 E. Braida, Il Romanzo del saggio Ahiqar: una proposta stemmatica .................. -

The Phonetics and Phonology of Assimilation and Gemination in Rural Jordanian Arabic

The phonetics and phonology of assimilation and gemination in Rural Jordanian Arabic by Mutasim Al-Deaibes A Thesis submitted to the Faculty of Graduate Studies of The University of Manitoba in partial fulfilment of the requirements of the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Department of Linguistics University of Manitoba Winnipeg, Manitoba, Canada Copyright © 2016 by Mutasim Al-Deaibes Abstract This dissertation explores the phonetics and phonology of voicing and emphatic assimilation across morpheme boundaries and investigates gemination word-medially and word-finally in Rural Jordanian Arabic (RJA). The results reveal that assimilation across morpheme boundaries behaves differently from assimilation across word boundaries in RJA. Vowel duration and vowel F1 were found robust parameters to indicate voicing assimilation. Similarly, F1, F2, and F3 were also adequate correlates to indicate emphatic assimilation. Phonologically, assimilation is best accounted for through the Sonority Hierarchy, Notion of Dominance, and Obligatory Contour Principle. For gemination, consonant as well as vowel durations were found robust acoustic correlates to discriminate geminates from singletons. Phonologically short vowels in the geminate context are significantly shorter than those in singleton context, while phonologically long vowels in geminate context are significantly longer than those in singleton context. The results indicate that the proportional differences between geminates and singletons based on word position and syllable structure are significantly different. Geminates word-medially are one and a half times longer than geminates word-finally. It has also been found that there is a temporal compensation between geminate consonants and the preceding vowels. Phonologically, geminates are best accounted for through prosodic weight rather than prosodic length. -

The Languages of Malta

The languages of Malta Edited by Patrizia Paggio Albert Gatt language Studies in Diversity Linguistics 18 science press Studies in Diversity Linguistics Chief Editor: Martin Haspelmath In this series: 1. Handschuh, Corinna. A typology of marked-S languages. 2. Rießler, Michael. Adjective attribution. 3. Klamer, Marian (ed.). The Alor-Pantar languages: History and typology. 4. Berghäll, Liisa. A grammar of Mauwake (Papua New Guinea). 5. Wilbur, Joshua. A grammar of Pite Saami. 6. Dahl, Östen. Grammaticalization in the North: Noun phrase morphosyntax in Scandinavian vernaculars. 7. Schackow, Diana. A grammar of Yakkha. 8. Liljegren, Henrik. A grammar of Palula. 9. Shimelman, Aviva. A grammar of Yauyos Quechua. 10. Rudin, Catherine & Bryan James Gordon (eds.). Advances in the study of Siouan languages and linguistics. 11. Kluge, Angela. A grammar of Papuan Malay. 12. Kieviet, Paulus. A grammar of Rapa Nui. 13. Michaud, Alexis. Tone in Yongning Na: Lexical tones and morphotonology. 14. Enfield, N. J (ed.). Dependencies in language: On the causal ontology of linguistic systems . 15. Gutman, Ariel. Attributive constructions in North-Eastern Neo-Aramaic. 16. Bisang, Walter & Andrej Malchukov (eds.). Unity and diversity in grammaticalization scenarios. 17. Stenzel, Kristine & Bruna Franchetto (eds). On this and other worlds: Voices from Amazonia. 18. Paggio, Patrizia & Albert Gatt (eds). The languages of Malta. ISSN: 2363-5568 The languages of Malta Edited by Patrizia Paggio Albert Gatt language science press Patrizia Paggio & Albert Gatt (eds.). -

Emphasis Harmony in Arabic: a Critical Assessment of Feature-Geometric and Optimality-Theoretic Approaches

languages Review Emphasis Harmony in Arabic: A Critical Assessment of Feature-Geometric and Optimality-Theoretic Approaches Hussein Al-Bataineh Department of Linguistics, Memorial University of Newfoundland, St. John’s, NL A1B 3S7, Canada; [email protected] Received: 23 July 2019; Accepted: 17 October 2019; Published: 21 October 2019 Abstract: This overview article examines vowel-consonant harmony, specifically emphatic harmony (also referred to as pharyngealization, velarization, or uvularization), which is found in Semitic languages. It provides a comprehensive overview of emphasis harmony in Arabic dialects from feature-geometric and optimality-theoretic perspectives. From the feature geometric account, emphatic consonants are considered as a natural class within the guttural group that has the [pharyngeal] or [RTR] ‘retracted tongue root’ feature. This view has been questioned and challenged recently by some researchers who argue for the exclusion of emphatics from the guttural group. The different arguments discussed in this paper show that researchers cannot reach a consensus regarding which consonants belong to the guttural group and which features are shared between these consonants. This paper shows that studies adopting an optimality-theoretic perspective provide a more comprehensive view of emphasis harmony and its fundamental aspects, namely, directional spreading and blocking, spread from secondary emphatic /r/ and labialization. However, this paper reaches two main conclusions. Firstly, unlike feature geometry, optimality theory can provide a clearer picture of emphasis harmony in an accurate and detailed way, which does not only clarify the process in one Arabic dialect but also describe the differences between dialects due to the merit of (re)ranking of constraints. Secondly, emphasis harmony is different from one Arabic dialect to another regarding its direction, involvement of emphatic /r/, and labialization. -

The Directionality of Emphasis Spread in Arabic

Remarks and Replies TheDirectionality of Emphasis Spread in Arabic JanetC. E.Watson Manymodern Arabic dialects exhibit asymmetries in the direction of emphasis(for most dialects, pharyngealization) spread. In a dialect ofYemeniArabic, emphasis has two articulatory correlates, pharyn- gealizationand labialization: within the phonological word, pharyn- gealizationspreads predominantly leftward, and labialization spreads rightward,targeting short high vowels. Since asymmetries in the direc- tionalityof spread of a secondaryfeature are phonetically motivated anddepend on whether the feature is anchored to the onset or the releasephase of the primary articulation, it is argued that the unmarked directionalityof spread should be encoded in the phonology as a markednessstatement on thatfeature. Keywords: Arabicdialects, emphasis, Grounded Phonology, labializa- tion,pharyngealization Thisarticle considers phonological emphasis in Arabic.It is dividedinto two parts. I firstdiscuss anarticle by Davis (1995) on asymmetriesin emphasisspread (spread of [RTR]) intwo dialects ofPalestinianArabic, and argue for thesignificance of directionality in emphasisspread. I then presentfurther supporting arguments for ahypothesisregarding directionality of spreadby consid- eringdata from S. an¨a¯n¯õ ,adialectof Yemeni Arabic, in which emphasis has two articulatory correlates,pharyngealization and labialization, and bydiscussingthe asymmetries in the direction- alityof spread,particularly of labialization,in this dialect. 1EmphasisSpread and Grounded Phonology Inan article on emphasis spread in two modern Palestinian dialects of Arabic, Davis (1995) adoptsGrounded Phonology (Archangeli and Pulleyblank 1994) to account for setsof opaque Thanksto Barry Heselwood for spectrographic analysis of my data andfor reading and commenting on various draftsof thisarticle; toJames Dickins;to Judith Broadbent; and to S.J.Hannahs,Mike Davenport, Phil Carr, andother members ofthe Phonology Reading Group at DurhamUniversity for providing critical comments onearlier versions.