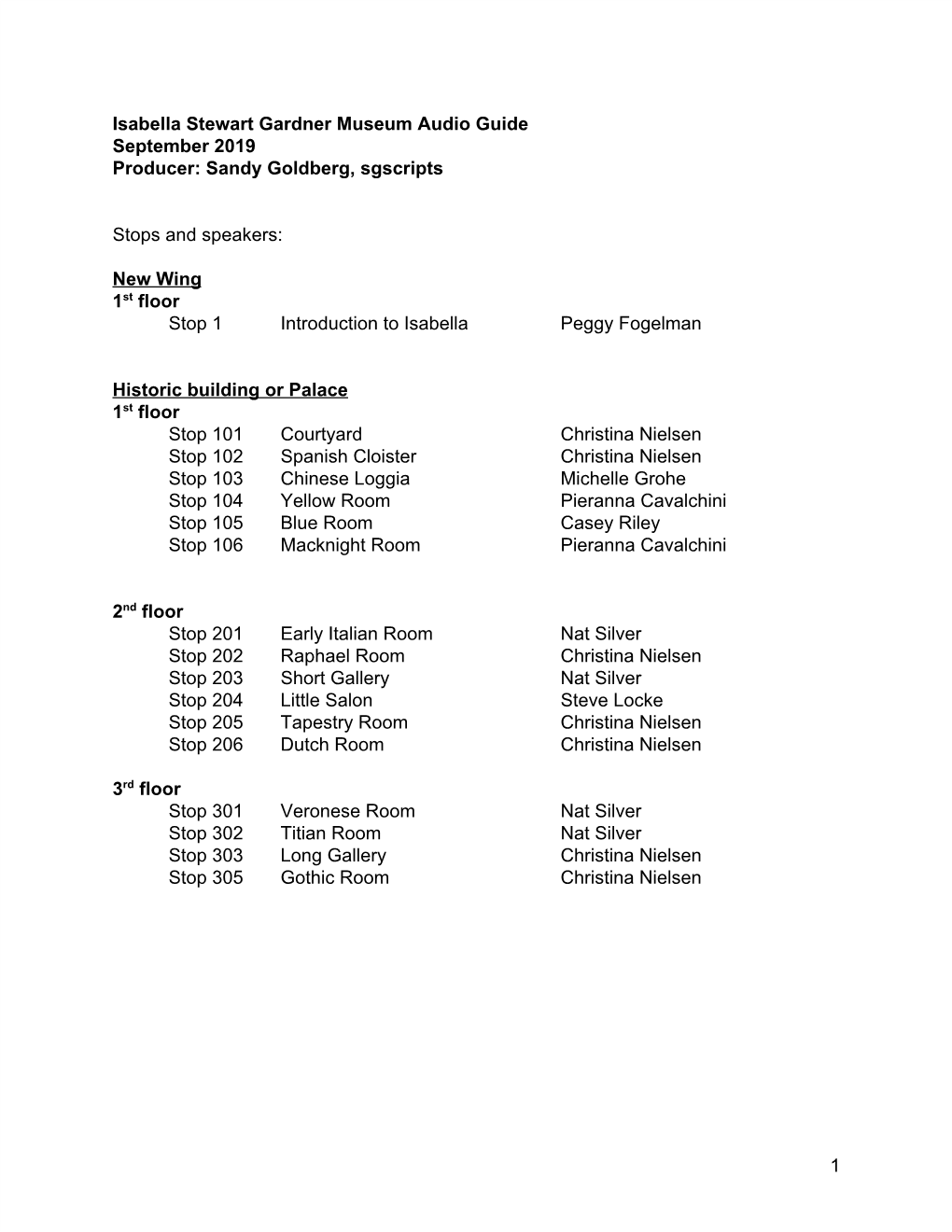

Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum Audio Guide September 2019 Producer: Sandy Goldberg, Sgscripts

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Long Gallery Educator’S Pack This Pack Contains Information Regarding the Contents and Themes of the Objects in the Long Gallery

Long Gallery Educator’s Pack This pack contains information regarding the contents and themes of the objects in the Long Gallery. On our website you can find further activities and resources to explore. The first exhibition in this gallery, ’Reactions’ focuses on Dundee’s nationally important collection of studio ceramics. This pack explores some of the processes that have created the stunning pieces on display and shares some of the inspirations behind the creation of individual ceramics. Contents Reactions: Studio Ceramics from our Collection Introduction and Origins 01 Studio Pottery - Influences 02 The Process 03 Glossary 05 List of Objects - by theme What is Studio Pottery? 10 Influences 11 Ideas and Stories 14 What on Earth is Clay? 16 Getting your Hands Dirty 19 The Icing on the Cake - Glaze and Decoration 21 Fire 24 Artist Focus Stephen Bird 27 Reactions: Studio Ceramics from our collection Introduction- background and beginnings 'Studio Ceramics' or 'Studio Pottery' - can be best described as the making of clay forms by hand in a small studio rather than in a factory. Where the movement in the early days is referred to as 'Studio Pottery' due to its focus on functional vessels and 'pots', the name of 'Studio Ceramics' now refers broadly to include work by artists and designers that may be more conceptual or sculptural rather than functional. As an artistic movement Studio Ceramics has a peculiar history. It is a history that includes changes in artistic and public taste, developments in art historical terms and small and very individual stories of artists and potters. -

6. the Tudors and Jacobethan England

6. The Tudors and Jacobethan England History Literature Click here for a Tudor timeline. The royal website includes a history of the Tudor Monarchs [and those prior and post this period]. Art This site will guide you to short articles on the Kings and Queens of the Tudor Music Dynasty. Another general guide to Tudor times can be found here. Architecture Click here for a fuller account of Elizabeth. One of the principle events of the reign of Elizabeth was the defeat of the Spanish Armada (here's the BBC Armada site). Elizabeth's famous (and short) speech before the battle can be found here. England's power grew mightily in this period, which is reflected in the lives and achievements of contemporary 'heroes' such as Sir Francis Drake, fearless fighter against the Spanish who circumnavigated the globe, and Sir Walter Raleigh (nowadays pronounced Rawley), one of those who established the first British colonies across the Atlantic (and who spelt his name in over 40 different ways...). Raleigh is generally 'credited' with the commercial introduction of tobacco into England .about 1778, and possibly of the potato. On a lighter note, information on Elizabethan costume is available here (including such items as farthingales and bumrolls). Literature Drama and the theatre The Elizabethan age is the golden age of English drama, for which the establishment of permanent theatres is not least responsible. As performances left the inn-yards and noble houses for permanent sites in London, the demand for drama increased enormously. While some of the smaller theatres were indoors, it is the purpose-built round/square/polygonal buildings such as The Theatre (the first, built in 1576), the Curtain (late 1570s?), the Rose (1587), the Swan (1595), the Fortune (1600) and of course the Globe (1599) that are most characteristic of the period. -

Weddings at Gunnersbury Mansion Let Us Make It a Day to Remember

WEDDINGS AT GUNNERSBURY MANSION LET US MAKE IT A DAY TO REMEMBER We welcome you to one of the most sought-after wedding venues in west London; Gunnersbury Park. Nestled between Chiswick and Ealing, Gunnersbury Park’s history dates back to the 11th century when it belonged to the Bishop of London. Over the centuries, ownership has passed through a succession of wealthy families and traces of its’ history can still be found in the landscape, planting and surviving buildings. Set in 72 acres of beautiful parkland, our Grade II* listed venue, Gunnersbury Park House, features a stunning suite of grand reception rooms, designed by architect Sydney Smirke in 1835 when the Rothschild family took ownership of the estate. Following recent restoration, it has been returned to its’ former glory and provides a magnificent backdrop for your wedding celebration, creating those precious moments and memories that will last a lifetime. So, whether you are looking for a small intimate ceremony for 10 or a larger, grand wedding reception for 150, Gunnersbury Park House is an elegant and distinctive setting - a unique space for your wedding. Our highly skilled and experienced team of Event Managers will provide you with a personalised and dedicated service and will be with you every step of the way. Be it flowers, photography, entertainment or transport, we pride ourselves on the standard of care and attention to detail we can bring to your special occasion. We are also delighted to be able to offer you specialised packages which can be tailored to suit your specific wedding requirements to ensure that you and your guests will have a perfect day. -

The Construction of Northumberland House and the Patronage of Its Original Builder, Lord Henry Howard, 1603–14

The Antiquaries Journal, 90, 2010,pp1 of 60 r The Society of Antiquaries of London, 2010 doi:10.1017⁄s0003581510000016 THE CONSTRUCTION OF NORTHUMBERLAND HOUSE AND THE PATRONAGE OF ITS ORIGINAL BUILDER, LORD HENRY HOWARD, 1603–14 Manolo Guerci Manolo Guerci, Kent School of Architecture, University of Kent, Marlowe Building, Canterbury CT27NR, UK. E-mail: [email protected] This paper affords a complete analysis of the construction of the original Northampton (later Northumberland) House in the Strand (demolished in 1874), which has never been fully investigated. It begins with an examination of the little-known architectural patronage of its builder, Lord Henry Howard, 1st Earl of Northampton from 1603, one of the most interesting figures of the early Stuart era. With reference to the building of the contemporary Salisbury House by Sir Robert Cecil, 1st Earl of Salisbury, the only other Strand palace to be built in the early seventeenth century, textual and visual evidence are closely investigated. A rediscovered eleva- tional drawing of the original front of Northampton House is also discussed. By associating it with other sources, such as the first inventory of the house (transcribed in the Appendix), the inside and outside of Northampton House as Henry Howard left it in 1614 are re-configured for the first time. Northumberland House was the greatest representative of the old aristocratic mansions on the Strand – the almost uninterrupted series of waterfront palaces and large gardens that stretched from Westminster to the City of London, the political and economic centres of the country, respectively. Northumberland House was also the only one to have survived into the age of photography. -

The Cosmos Club: a Self-Guided Tour of the Mansion

Founded 1878 The Cosmos Club - A Self-Guided Tour of the Mansion – 2121 Massachusetts Avenue, NW Washington, DC 20008 Founders’ Objectives: “The advancement of its members in science, literature, and art,” and also “their mutual improvement by social intercourse.” he Cosmos Club was founded in 1878 in the home of John Wesley Powell, soldier and explorer, ethnologist and T Director of the Geological Survey. Powell’s vision was that the Club would be a center of good fellowship, one that embraced the sciences and the arts, where members could meet socially and exchange ideas, where vitality would grow from the mixture of disciplines, and a library would provide a refuge for thought and learning. www.cosmosclub.org Welcome to The Townsend Mansion This brochure is designed to guide you on a walking tour of the public rooms of the Clubhouse. Whether member or guest, please enjoy the beauty surrounding you and our hospitality. You stand within an historic mansion, replete with fine and decorative arts belonging to the Cosmos Club. The Townsend Mansion is the fifth home of the Cosmos Club. Within the Clubhouse, Presidents, members of Congress, ambassadors, Nobel Laureates, Pulitzer Prize winners, scientists, writers, and other distinguished individuals have expanded their minds, solved world problems, and discovered new ways to make contributions to humankind, just as the founders envisioned in 1878. The history of the Cosmos Club is present in every room, not as homage to the past, but as a celebration of its continuum serving as a reminder of its origins, its genius, and its distinction. ❖❖❖ A place for conscious, animated discussion A place for quiet, contemplation and research A place to free the mind through relaxation, music, art, and conviviality Or exercise the mind and match wits A place of discovery A haven of friendship… The Cosmos Club A Brief History The Townsend Mansion, home of the Cosmos Club since 1952, was originally built in 1873 by Judge Curtis J. -

But Why: a Podcast for Curious Kids How Do

But Why: A Podcast for Curious Kids How Do You Make Paint? June 10, 2016 [00:00:00] Tell your parents now that you need this rock. Is going to do something cool with it. And it's worth it. [00:00:26] [Jane] I’m Jane Lindholm and this is But Why? A Podcast for Curious Lids from Vermont Public Radio. Every episode we take a question from you, our listeners, and we help find cool people to offer an answer for what's on your mind. [00:00:42] You can find all the instructions at butwhykids.org for how to record a question with an adult's help on a smartphone. We are getting some really incredible questions so keep them coming. Before we get started today, we're excited to announce a new sponsor. This episode of But Why? is supported by Seventh Generation asking “But why?”[00:01:03] for over 27 years. Why don't cleaning products have to list their ingredients on the label? Why are so many laundry detergents such crazy colors? Seventh Generation encourages kids of all ages to keep asking why. Learn more at seventhgeneration.com. OK, let's get to the show and hear today's questions. [00:01:27] [Addison] My name is Addison Bee. I am five years old and I live in Edmonds, Washington and I want to know about how we make paints. [00:01:39] [Jane] There are a lot of different ways that paint is made. If you're painting your house, you're probably using industrial paint that was made in a very big factory. -

Valeska Soares B

National Museum of Women in the Arts Selections from the Collection Large-Print Object Labels As of 8/11/2020 1 Table of Contents Instructions…………………………………………………..3 Rotunda……………………………………………………….4 Long Gallery………………………………………………….5 Great Hall………………….……………………………..….18 Mezzanine and Kasser Board Room…………………...21 Third Floor…………………………………………………..38 2 National Museum of Women in the Arts Selections from the Collection Large-Print Object Labels The large-print guide is ordered presuming you enter the third floor from the passenger elevators and move clockwise around each gallery, unless otherwise noted. 3 Rotunda Loryn Brazier b. 1941 Portrait of Wilhelmina Cole Holladay, 2006 Oil on canvas Gift of the artist 4 Long Gallery Return to Nature Judith Vejvoda b. 1952, Boston; d. 2015, Dixon, New Mexico Garnish Island, Ireland, 2000 Toned silver print National Museum of Women in the Arts, Gift of Susan Fisher Sterling Top: Ruth Bernhard b. 1905, Berlin; d. 2006, San Francisco Apple Tree, 1973 Gelatin silver print National Museum of Women in the Arts, Gift from the Trustees of the Corcoran Gallery of Art (Gift of Sharon Keim) 5 Bottom: Ruth Orkin b. 1921, Boston; d. 1985, New York City Untitled, ca. 1950 Gelatin silver print National Museum of Women in the Arts, Gift of Joel Meyerowitz Mwangi Hutter Ingrid Mwangi, b. 1975, Nairobi; Robert Hutter, b. 1964, Ludwigshafen am Rhein, Germany For the Last Tree, 2012 Chromogenic print National Museum of Women in the Arts, Gift of Tony Podesta Collection Ecological concerns are a frequent theme in the work of artist duo Mwangi Hutter. Having merged names to identify as a single artist, the duo often explores unification 6 of contrasts in their work. -

Excerpted from Bernard Berenson and the Picture Trade

1 Bernard Berenson at Harvard College* Rachel Cohen When Bernard Berenson began his university studies, he was eighteen years old, and his family had been in the United States for eight years. The Berensons, who had been the Valvrojenskis when they left the village of Butrimonys in Lithuania, had settled in the West End of Boston. They lived near the North Station rail yard and the North End, which would soon see a great influx of Eastern European Jews. But the Berensons were among the early arrivals, their struggles were solitary, and they had not exactly prospered. Albert Berenson (fig. CC.I.1), the father of the family, worked as a tin peddler, and though he had tried for a while to run a small shop out of their house, that had failed, and by the time Berenson began college, his father had gone back to the long trudging rounds with his copper and tin pots. Berenson did his first college year at Boston University, but, an avid reader and already a lover of art and culture, he hoped for a wider field. It seems that he met Edward Warren (fig. CC.I.16), with whom he shared an interest in classical antiquities, and that Warren generously offered to pay the fees that had otherwise prevented Berenson from attempting to transfer to Harvard. To go to Harvard would, in later decades, be an ambition of many of the Jews of Boston, both the wealthier German and Central European Jews who were the first to come, and the poorer Jews, like the Berensons, who left the Pale of Settlement in the period of economic crisis and pogroms.1 But Berenson came before this; he was among a very small group of Jewish students, and one of the first of the Russian Jews, to go to Harvard. -

Stained Glass Conservation at the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum

Article: Stained glass conservation at the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum: Putting the pieces together Author(s): Valentine Talland and Barbara Mangum Source: Objects Specialty Group Postprints, Volume Four, 1996 Pages: 86-98 Compilers: Virginia Greene and John Griswold th © 1996 by The American Institute for Conservation of Historic & Artistic Works, 1156 15 Street NW, Suite 320, Washington, DC 20005. (202) 452-9545 www.conservation-us.org Under a licensing agreement, individual authors retain copyright to their work and extend publications rights to the American Institute for Conservation. Objects Specialty Group Postprints is published annually by the Objects Specialty Group (OSG) of the American Institute for Conservation of Historic & Artistic Works (AIC). A membership benefit of the Objects Specialty Group, Objects Specialty Group Postprints is mainly comprised of papers presented at OSG sessions at AIC Annual Meetings and is intended to inform and educate conservation-related disciplines. Papers presented in Objects Specialty Group Postprints, Volume Four, 1996 have been edited for clarity and content but have not undergone a formal process of peer review. This publication is primarily intended for the members of the Objects Specialty Group of the American Institute for Conservation of Historic & Artistic Works. Responsibility for the methods and materials described herein rests solely with the authors, whose articles should not be considered official statements of the OSG or the AIC. The OSG is an approved division of the AIC but does not necessarily represent the AIC policy or opinions. STAINED GLASS CONSERVATION AT THE ISABELLA STEWART GARDNER MUSEUM: PUTTING THE PIECES TOGETHER Valentine Talland and Barbara Mangum Introduction In the Spring of 1994 the Gardner Museum began the conservation of nine medieval and Renaissance stained glass windows in its permanent collection. -

Botticelli: Heroines + Heroes on View: February 14, 2019 – May 19, 2019

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE Botticelli: Heroines + Heroes On View: February 14, 2019 – May 19, 2019 Sandro Botticelli (Italian, 1444 or 1445-1510), The Tragedy of Lucretia, 1499-1500. Tempera and oil on panel, 83.8 x 176.8 cm (33 x 69 5/8 in.) Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum, Boston (P16e20) BOSTON, MA (October 2018) – For the forthcoming Botticelli: Heroines + Heroes exhibition in early 2019, the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum will be the sole venue in the United States to reunite Renaissance master Sandro Botticelli’s The Story of Lucretia from the Gardner Museum collection with the painter’s Story of Virginia, on loan from Italy for the first time. This presentation explores Botticelli’s revolutionary narrative paintings and brings them into dialogue with contemporary responses. The exhibition opens Feb. 14, 2019 and runs through May 19, 2019. Painted around 1500, eight monumental works – including important loans from museums in Europe and the U.S. - demonstrate Botticelli’s extraordinary talent as a master storyteller. He reinvented ancient Roman and early Christian heroines and heroes as role models, transforming their stories of lust, betrayal, and violence into parables for a new era of political and religious turmoil. Considered one of the most renowned artists of the Renaissance, Botticelli (about 1445-1510) was sought after by popes, princes, and prelates for paintings to decorate Italian churches. His Medici-era madonnas elevated Botticelli to a household name in Gilded Age Boston. Yet the painter achieved iconic status through his secular paintings for domestic interiors – like the Primavera. All of the works in the Gardner’s exhibition originally filled the palaces of Florence, adorning patrician bedrooms with sophisticated modern spins on ancient tales. -

Best of ITALY

TRUTH IN TRAVEL TRUTH IN TRAVEL Best of ITALY VENICE & THE NORTH PAGE S 2–9 Venice Milan VENICE NORTHERN The Prince of Venice ITALY Viewing Titian’s paintings in their original basilicas and palazzi reveals a Venice of courtesans and intrigue. Pulitzer Prize—winning critic Manuela Hoelterhoff’s walking guide to the city amplifies the experience of reliving the tumultuous times of Florence the Old Master—and finds some aesthetically pleasing hotels and restaurants along the way. TUSCANY (Trail of Glory map on page 5) FLORENCE & TUSCANY PAGE S 10 –1 5 Best of ITALYCENTRAL ITALY TUSCAN COAST Rome Tuscany by the Sea Believe it or not, Tuscany has a shoreline—145 miles of it, with ports large and small, hidden beaches, a rich wildlife preserve, and, of course, the blessings of the Italian table. Clive Irving Naples discovers a sexy combo of coast, cuisine, and Pompeii Caravaggio—and customizes a beach-by-beach, Capri harbor-by-harbor map for seaside fun. SARDINIA SOUTHERN ITALY ROME & CENTRAL ITALY PAGE S 16–2 0 ROME Treasures of the Popes You’re in Rome, but the Vatican is a city in itself. (In fact, a nation.) What should you see? John Palermo Julius Norwich picks his masterpieces, and warns of the potency of Vatican hospitality. SICILY VENICE & THE NORTH PAGE 2 Two miles long, spanned by three bridges and six gondola ferries, the Grand Canal is an avenue of palaces built between the fourteenth and eigh- teenth centuries. A rich, luminous city, her beauty reflected at every turn, Venice was the perfect muse for an ambitious Renaissance artist. -

Office of Performance Management & Oversight

OFFICE OF PERFORMANCE MANAGEMENT & OVERSIGHT FISCAL 2014 ANNUAL REPORT GUIDANCE The Office of Performance Management & Oversight (OPMO) measures the performance of all public and quasi‐public entities engaged in economic development. All agencies are required to submit an Annual Report demonstrating progress against plan and include additional information as outlined in Chapter 240 of the Acts of 2010. The annual reports of each agency will be published on the Office of Performance Management website, and will be electronically submitted to the clerks of the Senate and House of Representatives, the Chairs of the House and Senate Committees on Ways and Means and the House and Senate Chairs of the Joint Committee on Economic Development and Emerging Technologies. Filing Instructions: The Fiscal Year 2014 report is due no later than Friday, October 3, 2014. An electronic copy of the report and attachments A & B should be e‐mailed to [email protected] 1) AGENCY INFORMATION Agency Name Massachusetts Cultural Council Agency Head Anita Walker Title Executive Director Website www.massculturalcouncil.org Address 10 St. James Avenue, Boston, MA 02116 2) MISSION STATEMENT Please include the Mission Statement for your organization below. Building Creative Communities. Inspiring Creative Minds. OUR MISSION The Massachusetts Cultural Council (MCC) is a state agency that promotes excellence, access, education, and diversity in the arts, humanities, and interpretive sciences to improve the quality of life for all Massachusetts residents and contribute to the economic vitality of our communities. The Council pursues this mission through a combination of grant programs, partnerships, and services for nonprofit cultural organizations, schools, communities, and artists.