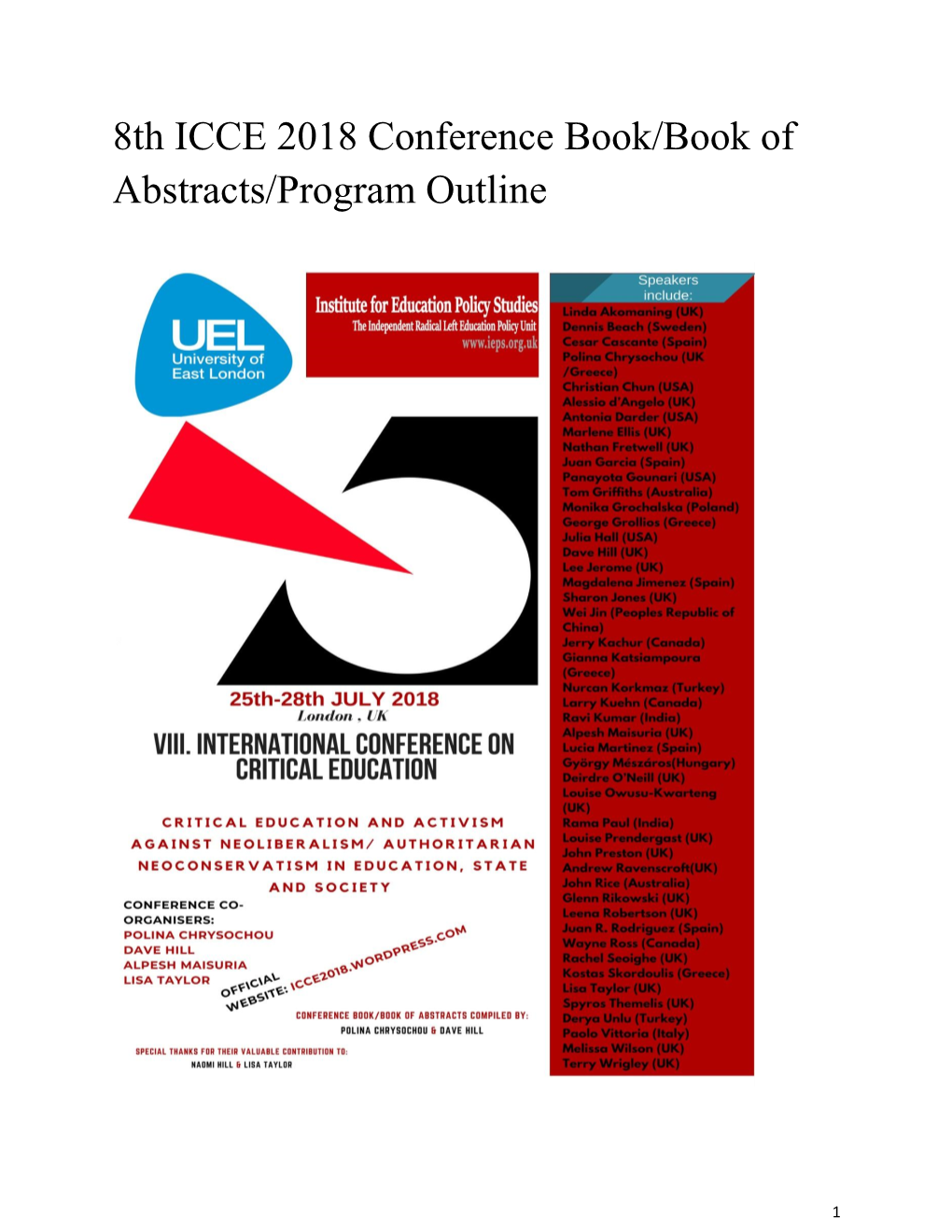

8Th ICCE 2018 Conference Book/Book of Abstracts/Program

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Critical Education

Critical Education Volume 6 Number 19 October 15, 2015 ISSN 1920-4125 The Corporate University An E-interview with Dave Hill, Alpesh Maisuria, Anthony Nocella, and Michael Parenti Emil Marmol University of Toronto Alpesh Maisuria University of East London Dave Hill Anglia Ruskin University Anthony Nocella Dispute Resolution Institute at the Hamline Law School Michael Parenti Independent Scholar Citation: Marmol, E. (2015). The corporate university: An e-interview with Dave Hill, Alpesh Maisuria, Anthony Nocella, and Michael Parenti. Critical Education, 6(19). Retrieved from http://ojs.library.ubc.ca/index.php/criticaled/article/view/185102 Abstract Since the neo-liberal turn, corporate investment in universities has accelerated as the withdrawal of government funding, among other factors, has further exposed universities to market forces. While this process offers numerous benefits for corporations and wealthy individuals, it has been mostly detrimental for students, educators, and the public at large. In this interview, international scholars Dave Hill, Alpesh Maisuria, Anthony Nocella, and Michael Parenti broadly explain why corporations have been aggressively investing in universities. They address the numerous ways that corporate involvement in university activity negatively impacts academic freedom, research outcomes, and the practice of democracy. The interview ends on a hopeful note by presenting examples of resistance against corporate influence. Their analyses focus primarily on the United States, United Kingdom, and Canada. Readers are free to copy, display, and distribute this article, as long as the work is attributed to the author(s) and Critical Education, it is distributed for non-commercial purposes only, and no alteration or transformation is made in the work. -

Final Program

INTERNATIONAL CONFERENCE ON CRITICAL EDUCATION ATHENS 12-16 JULY 2011 CONFERENCE PROGRAM TUESDAY 12 JULY OPENING CEREMONY Central Building University of Athens – Propylaea, 30 Panepistimiou st. Athens center 11:00 – 11:10 Prof. Kostas Skordoulis Local Organizing Committee 11:10 – 11:25 Office of the Rector University of Athens 11:25 – 11:35 Prof. Athanasios Trilianos Department of EDucation- President 11:35 – 11:40 A/ Prof. Konstantinos Malafantis PresiDent of the Hellenic PeDagogical Society 11:40 – 11:50 Prof. Efthymios Nicolaidis PresiDent of the Hellenic Society of History, Philosophy anD DiDactics of Science 11:50 – 12:30 Prof. Dave Hill International Organizing Committee 12:30 – 13:30 PLENARY SPEECH Prof. Aristides Baltas (National Technical University of Athens) “Teaching raDically novel physical theories: the role of nonsense” 13:30 – 17:00 LUNCH BREAK EVENING SESSION Marasleion Academy Building, 4 Marasli st. 17:00 – 18:00 REGISTRATION ROOM 1 ROOM 2 ROOM 3 ROOM 4 ROOM 5 18:00 – 18:30 Alpesh Maisuria Alexandra Lekka & Amima Sayeed Beatrice Dike Alessandra Troian & “A Critical Examination of Theodore Alexiou “The Balancing Act: “Critical Reflective Marcelo Leandro Eichler Critical Race Theory in “Science anD Memory: Critical Education vs Practice with "Alice" “Extension or Education” Critical pedagogy and Cultural Values and communication? – The Museum Learning” Traditions” role of rural extension anD 2 the Framework Convention on Tobacco Control in the perceptions of tobacco farmers…. 18:30 – 19:00 Anastasia Liasidou Achilleas -

Gallery Trail 2018

Buck’s-horn plantain Buck’s-horn Sea beet From Newlyn Art The Rain it From The Exchange, follow the red Gallery, follow the red Raineth Every Day numbers in descending order, numbers in ascending on your walk to Newlyn Art Gallery order, on your walk to 12 4 Pirates! NEW STREET The Exchange The Exchange CHAPEL STREET 10 NEWLYN ART GALLERY 11 Union New Road, Newlyn, Penzance TR18 5PZ Hotel THE EXCHANGE Princes Street, Penzance TR18 2NL Brick face Tidal observatory Penzance’s pink prom newlynartgallery.co.uk 01736 363715 A L Church St Mary’s E X OPEN Summer Mon - Sat, Winter Tue - Sat, 10.00 – 17.00 A 9 GALLERY TRAIL N D The Egyptian House R BUSES run from The Greenmarket to A Admiral Benbow R 8 Newlyn Art Gallery every 15 - 30 mins. O A Newlyn Art Gallery 5 D D R A Y Facts and information supplied by Bryony Rylett EL WESTERN PR 7 P OMENADE R A Leaflet design by SPY Design and Publishing Ltd. AD OAD H RO NEW Educational Charity: 273785 Fishermen’s memorial Fishermen’s VAT Number: 133 1322 23 1 UNDER C How to use this map: 3 Limited Company Number: 1310070 The Jubilee pool Follow the route indicated and every FREE time you see a number ( 1 ), you will ROUTE 6 find a brief description of the site @newlynexchange GALLERYMAP TRAIL 2 overleaf. ROUTE MAP MOUNTS BAY Gallery Trail statue and raised the money to pay for it and its by pirates. Boats were captured, fishermen does not stop waves, sometimes as high style is Commissioner’s Gothic. -

Work Placement Handbook

Work Placement Handbook 2012 CONTENTS • Background to Falmouth Art Gallery • Falmouth Art Gallery’s Work placement Policy • Work placement Benefits • Getting the most from the placement • Guidelines General Safety Health Object Handling Supervision • Staff Lists • Forms Falmouth Art Gallery Falmouth Art gallery is a service funded by Falmouth Town Council. It is an accredited museum and complies with standards laid down for the Registration of Museums in the United Kingdom and works in partnership with: Age Concern, The Art Fund, Arts Council England, Brightwater Holidays, Combined Universities of Cornwall, Cornwall and Devon Media, Cornwall College, Cornwall Council Conservation Department, Cornwall Heritage Trust, CSV RSVP, Earls Retreat, Falmouth Arts Society, Falmouth BIDS, Falcare (formerly Mencap), Falmouth Marine School, Falmouth Stroke Club, Heritage Lottery Fund, Hine Downing Solicitors, Jason Thomas Dance Company, Kerrier Pupil Referral Unit, Kids in Museums, Langholme, Little Parc Owles Trust, Local schools, MLA (Museums, Libraries and Archives Council), MLA/V&A Purchase Grant Fund, Museums Association, National Maritime Museum Cornwall, Newquay Zoo, Penlee House Gallery & Museum, Royal Cornwall Museum, Royal Cornwall Polytechnic Society, Sully’s Picture Framing Penryn, Susie Group (victims of domestic abuse), Swamp Circus, Tate St Ives, The Tanner Trust, Truro and Penwith College, U3A, University College Falmouth, University of Exeter, Wayfarers,The West End Group – Murdoch and Trevithick Centre, The WILD Young Parents Group Falmouth Art Gallery The Origins of the Collection The first Falmouth Art Gallery was opened in Grove Place in 1894 under the Directorship of William Ayerst Ingram and Henry Scott Tuke. It featured their own work along with that of Sophie Anderson, Richard Harry Carter, Charles Davidson, Topham Davidson, Winifred Freeman and Charles Napier Hemy. -

The Constant Times VOLUME 8, ISSUE 1

V OLUME 8, I SSUE 1 The Constant Times F EBRUARY /MARCH 2019 Constantine School’s 50th Christingle service Cags Gilbert, Head of School At Constantine School we have been extremely lucky to fit in several vis- its to our village church in the last month. We sang alongside Mawnan School for the Advent Carol Service and also celebrated the 50th year of the Christin- gle at our own school service. More Constantine School news on Page 2. Also in this issue... Page 3 Collector returns constable’s staff Page 4 If you go down to the woods today... Page 8 Christmas Lights reflections Page 9 Transition’s second helping Page 11 Garden Society photo quiz Page 16 The Passmore Edwards legacy Page 2 Volume 8, Issue 1 Constantine School news (Cont’d) Discovering the deep….. Year 4 have been learning about our Awesome Oceans and local fisher- man, Cameron, came in to show us our favourite species and they were all alive! Straight from the morning’s catch, he arrived excitedly to tell us some of what he knew as we were keen to listen to him and ask questions. We learnt so much about life-cycles, their habitats, mating, adaptations and we also got to handle some pretty big and live shell fish. It was so much fun! AN APPEAL TO ALL DOG OWNERS FROM THE EDITOR There’s no easy way of putting this, but despite previous complaints, some irresponsible dog owners are still allowing their animals to foul the grass verge beside the school. This is especially unpleasant and a potential health risk for school and pre-school children. -

Although Many European Radical Left Parties

Peace, T. (2013) All I'm asking, is for a little respect: assessing the performance of Britain's most successful radical left party. Parliamentary Affairs, 66(2), pp. 405-424. There may be differences between this version and the published version. You are advised to consult the publisher’s version if you wish to cite from it. http://eprints.gla.ac.uk/144518/ Deposited on: 21 July 2017 Enlighten – Research publications by members of the University of Glasgow http://eprints.gla.ac.uk 2 All I’m asking, is for a little Respect: assessing the performance of Britain’s most successful radical left party BY TIMOTHY PEACE1 ABSTRACT This article offers an overview of the genesis, development and decline of the Respect Party, a rare example of a radical left party which has achieved some degree of success in the UK. It analyses the party’s electoral fortunes and the reasons for its inability to expand on its early breakthroughs in East London and Birmingham. Respect received much of its support from Muslim voters, although the mere presence of Muslims in a given area was not enough for Respect candidates to get elected. Indeed, despite criticism of the party for courting only Muslims, it did not aim to draw its support from these voters alone. Moreover, its reliance on young people and investment in local campaigning on specific political issues was often in opposition to the traditional ethnic politics which have characterised the electoral process in some areas. When the British public awoke on the morning of Friday 6th May 2005 most would have been unsurprised to discover that the Labour Party had clung on to power but with a reduced majority, as had been widely predicted. -

Class Struggle and Education: Neoliberalism, (Neo)-Conservatism, and the Capitalist Assault on Public Education’, Critical Education

South Asian University, Delhi, 22-23 March 2014 Transformative Education, Critical Education, Marxist Education: Possibilities and Alternatives to the Restructuring of Education in Global Neoliberal / Neoconservative Times Dave Hill Research Professor of Education at Anglia Ruskin University Faculty of Health, Social Care and Education Anglia Ruskin University Chelmsford Campus Bishop Hall Lane Chelmsford, CM11SQ, England Work Phone: +44 845271333 Home Phone: +441273270943 Mobile Phone: +44 7973194357 TOTAL WORD COUNT: 6,742 words Transformative Education, Critical Education, Marxist Education: Possibilities and Alternatives to the Restructuring of Education in Global Neoliberal / Neoconservative Times Abstract This paper briefly examines the context-specific paths and policies of neoliberalism and neoconservatism and the resistance to their depradations. While calling for activism with micro-, meso- and macro-social and political arenas, the paper focuses on activity within formal education institutions. It suggests a series of measures- a socialist Manifesto for education, for discussion. It concludes with a call to action for teachers and education workers (and others) to be “Critical Educators,” Resistors, Marxist activists, within and outside official education. Neoliberalism and (Neo)-conservatism and The Nature and Power of the Resistance The paths of neoliberalisation and (neo)-conservatism are similar in many countries. But each country has its own history, has its own particular context; each country has its own balance of class forces, its own level of organization of the working class and the capitalist class, and different levels of confidence within the working class and within the capitalist class. In countries where resistance to neoliberalism is very strong, as in Greece, then the government has found it actually so far very difficult to engage in large-scale privatization. -

A Critique of the Statistical Basis for Critical Race Theory in Britain: and Some Political Implications

Race and Class in Britain: a Critique of the statistical basis for Critical Race Theory in Britain: and some political implications Dave Hill University of Northampton, UK, and Middlesex University, London, UK Journal for Critical Education Policy Studies, vol.7. no.2 Summary In this paper I critique what I analyse as the misuse of statistics in arguments put forward by some Critical Race Theorists in Britain showing that `Race‟ `trumps‟ Class in terms of underachievement at 16+ exams in England and Wales. I ask two questions, and make these two associated criticisms, concerning the representation of these statistics: 1. With respect to `race‟ and educational attainment, what is the validity of ignoring the presence of the (high achieving) Indian/ Indian heritage group of pupils- one of the two largest minority groups in England and Wales? This group has been ignored, indeed, left completely out of statistical representations- charts- showing educational achievement levels of different ethnic groups. 2. With respect to social class and educational attainment, what is the validity of selecting two contiguous social class/ strata in order to show social class differences in educational attainment? (1) At a theoretical level, using Marxist work (2) I argue for a notion of `raced‟ and gendered class, in which some (but not all) minority ethnic groups are racialised or xeno-racialised) and suffer a `race penalty‟ in, for example, teacher labelling and expectation, treatment by agencies of the state, such as the police, housing, judiciary, health services and in employment. I critique some CRT treatment of social class analysis and underachievement as unduly dismissive and extraordinarily subdued (e.g. -

Unitarian Members of Parliament in the Nineteenth Century

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Stirling Online Research Repository Unitarian Members of Parliament in the Nineteenth Century A Catalogue D. W. Bebbington Professor of History, University of Stirling The catalogue that follows contains biographical data on the Unitarians who sat in the House of Commons during the nineteenth century. The main list, which includes ninety-seven MPs, is the body of evidence on which the paper on „Unitarian Members of Parliament in the Nineteenth Century‟ is based. The paper discusses the difficulty of identifying who should be treated as a Unitarian, the criterion chosen being that the individual appears to have been a practising adherent of the denomination at the time of his service in parliament. A supplementary list of supposed Unitarian MPs, which follows the main list, includes those who have sometimes been identified as Unitarians but who by this criterion were not and some who may have been affiliated to the denomination but who were probably not. The borderline is less sharp than might be wished, and, when further research has been done, a few in each list may need to be transferred to the other. Each entry contains information in roughly the same order. After the name appear the dates of birth and death and the period as an MP. Then a paragraph contains general biographical details drawn from the sources indicated at the end of the entry. A further paragraph discusses religious affiliation and activities. Unattributed quotations with dates are from Dod’s Parliamentary Companion, as presented in Who’s Who of British Members of Parliament. -

Global Neoliberalism and Education and Its Consequences Routledge Studies in Education and Neoliberalism EDITED by DAVE HILL, University of Northampton, UK

Global Neoliberalism and Education and its Consequences Routledge Studies in Education and Neoliberalism EDITED BY DAVE HILL, University of Northampton, UK 1. The Rich World and the Impoverishment of Education Diminishing Democracy, Equity and Workers’ Rights Edited by Dave Hill 2. Contesting Neoliberal Education Public Resistance and Collective Advance Edited by Dave Hill 3. Global Neoliberalism and Education and its Consequences Edited by Dave Hill and Ravi Kumar 4. The Developing World and State Education Neoliberal Depredation and Egalitarian Alternatives Edited by Dave Hill and Ellen Rosskam Global Neoliberalism and Education and its Consequences Edited by Dave Hill and Ravi Kumar New York London First published 2009 by Routledge 270 Madison Ave, New York, NY 10016 Simultaneously published in the UK by Routledge 2 Park Square, Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxon OX14 4RN This edition published in the Taylor & Francis e-Library, 2008. “To purchase your own copy of this or any of Taylor & Francis or Routledge’s collection of thousands of eBooks please go to www.eBookstore.tandf.co.uk.” Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group, an informa business © 2009 Taylor & Francis All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical, or other means, now known or hereaf- ter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers. Trademark Notice: Product or corporate names may be trademarks or registered trade- marks, and are used only for identification and explanation without intent to infringe. -

Free Copy Thanks to Our Volunteers and Advertisers. Circulation 2500

Issue 126 April/May 2016 Happy Birthday to the Passmore Edwards Institute. On the 29th of April 1896, to the accompaniment of a band and with a full civic reception including banners across the street, John Passmore Edwards officially opened the Passmore Edwards Institute. This fine building was designed by Mr. Silvanus Τreνail and built by Messrs. John Symons and Son, of Blackwater. 2016 is the Institute’s 120th birthday. John Passmore Edwards had grown up in impoverished circumstances in nearby Blackwater and had had little opportunity for reading and learning. According to his autobiography, he often longed for books and a comfortable room in which to read them. Continued page 3 Free copy thanks to our Issue 126 volunteers and advertisers. Circulation 2500 1 Hayle Pump Newsletter Passmore Edwards Institute, 13-15 Hayle Terrace TR27 4BU The Pump is produced by volunteers as a community newsletter. NB All articles accepted are not necessarily the view of the editorial team. Editorial team contact Subscriptions [email protected] For 6 issues by post , please send a cheque or postal order for £3.60 Advertising Jeff Turk made out to Hayle Pump Newsletter [email protected] to: Phone 01736 752319 Hayle Pump Subscriptions Web site John Bennett 35 Penpol Terrace, [email protected] Hayle TR27 4BQ Please give your name and number Team members as well as the delivery name and Samuel Marsden address. Mary Cambridge Sarah Turk Send any articles or copy to [email protected] Send your adverts to [email protected] or use or drop off at drop off points Angove Sports (Copperhouse) Advertising Rates The Farm Shop (Foundry) Passmore Edwards Institute 1/8 63 x 47.5 £10 (opposite War Memorial) 1/4 63 x 95 £15 NEXT DEADLINE is 1/2 Not available 13th May 2 continued from Page 1 He had been taught by a disabled miner and was aware of the limited opportunities for advancement that ordinary people had. -

June 23 - 26, 2014

June 23 - 26, 2014 IV INTERNATIONAL CONFERENCE ON CRITICAL EDUCATION Critical Education in the Era of Crisis Conference’s Proceedings Editors: George Grollios, Anastasios (Tassos) Liambas, Periklis Pavlidis ISBN: 978-960-243-698-1 Full Reference Grollios, G., Liambas, A. & Pavlidis, P. (2015). Proccedings of the IV International Conference on Critical Education “Critical Education in the Era of Crisis”, pp. ff-gg, http://www.eled.auth.gr/, date of access mm/dd/yy. International Organizing Committee Chair: Dave Hill (Anglia Ruskin University, UK) Co-chair : George Grollios (Aristotle University of Thessaloniki, Greece) Members Ahmet Yıldız (Ankara University, Turkey) Alexandros Chrisis (Panteon University, Greece) Alpesh Maisuria (University of East London, London, UK) Antonis Lenakakis (Aristotle University of Thessaloniki, Greece) Argyris Kyrides (Aristotle University of Thessaloniki, Greece) Ayhan Ural (Gazi University, Turkey) Bessie Mitsikopoulou ((National and Kapodistrian University of Athens, Greece) Bill Templer (Editor of JCEPS – Eastern Europe) Brad Porfilio (Lewis University, Illinois, USA) Christodoula Mitakidou (Aristotle University of Thessaloniki, Greece) Christos Antoniou (Aristotle University of Thessaloniki, Greece) Christos Tzikas (Aristotle University of Thessaloniki, Greece) Curry Malott (West Chester University, Pennsylvania, USA) Deborah Kelsh (College of St. Rose, Albany NY, USA) Dennis Beach (University of Göteburg, Sweden) Despoina Desli (Aristotle University of Thessaloniki, Greece) Dimitris Charalambous (Aristotle