In Search of the Original Form of Korean Culture

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Marxism, Stalinism, and the Juche Speech of 1955: on the Theoretical De-Stalinization of North Korea

Marxism, Stalinism, and the Juche Speech of 1955: On the Theoretical De-Stalinization of North Korea Alzo David-West This essay responds to the argument of Brian Myers that late North Korean leader Kim Il Sung’s Juche speech of 1955 is not nationalist (or Stalinist) in any meaningful sense of the term. The author examines the literary formalist method of interpretation that leads Myers to that conclusion, considers the pro- grammatic differences of orthodox Marxism and its development as “Marx- ism-Leninism” under Stalinism, and explains that the North Korean Juche speech is not only nationalist, but also grounded in the Stalinist political tradi- tion inaugurated in the Soviet Union in 1924. Keywords: Juche, Nationalism, North Korean Stalinism, Soviet Stalinism, Socialism in One Country Introduction Brian Myers, a specialist in North Korean literature and advocate of the view that North Korea is not a Stalinist state, has advanced the argument in his Acta Koreana essay, “The Watershed that Wasn’t” (2006), that late North Korean leader Kim Il Sung’s Juche speech of 1955, a landmark document of North Korean Stalinism authored two years after the Korean War, “is not nationalist in any meaningful sense of the term” (Myers 2006:89). That proposition has far- reaching historical and theoretical implications. North Korean studies scholars such as Charles K. Armstrong, Adrian Buzo, Seong-Chang Cheong, Andrei N. Lankov, Chong-Sik Lee, and Bala、zs Szalontai have explained that North Korea adhered to the tactically unreformed and unreconstructed model of nationalist The Review of Korean Studies Volume 10 Number 3 (September 2007) : 127-152 © 2007 by the Academy of Korean Studies. -

"Mostly Propaganda in Nature": Kim Il Sung, the Juche Ideology, and The

NORTH KOREA INTERNATIONAL DOCUMENTATION PROJECT WORKING PAPER #3 THE NORTH KOREA INTERNATIONAL DOCUMENTATION PROJECT WORKING PAPER SERIES Christian F. Ostermann and James F. Person, Series Editors This paper is one of a series of Working Papers published by the North Korea International Documentation Project of the Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars in Washington, D.C. Established in 2006 by a grant from the Korea Foundation, and in cooperation with the University of North Korean Studies (Seoul), the North Korea International Documentation Project (NKIDP) addresses the scholarly and policymaking communities’ critical need for reliable information on the North Korean political system and foreign relations by widely disseminating newly declassified documents on the DPRK from the previously inaccessible archives of Pyongyang’s former communist allies. With no history of diplomatic relations with Pyongyang and severely limited access to the country’s elite, it is difficult to for Western policymakers, journalists, and academics to understand the forces and intentions behind North Korea’s actions. The diplomatic record of North Korea’s allies provides valuable context for understanding DPRK policy. Among the activities undertaken by the project to promote this aim are a section in the periodic Cold War International History Project BULLETIN to disseminate new findings, views, and activities pertaining to North Korea in the Cold War; a fellowship program for Korean scholars working on North Korea; international scholarly meetings, conferences, and seminars; and publications. The NKIDP Working Paper Series is designed to provide a speedy publications outlet for historians associated with the project who have gained access to newly- available archives and sources and would like to share their results. -

Surviving Through the Post-Cold War Era: the Evolution of Foreign Policy in North Korea

UC Berkeley Berkeley Undergraduate Journal Title Surviving Through The Post-Cold War Era: The Evolution of Foreign Policy In North Korea Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/4nj1x91n Journal Berkeley Undergraduate Journal, 21(2) ISSN 1099-5331 Author Yee, Samuel Publication Date 2008 DOI 10.5070/B3212007665 Peer reviewed|Undergraduate eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California Introduction “When the establishment of ‘diplomatic relations’ with south Korea by the Soviet Union is viewed from another angle, no matter what their subjective intentions may be, it, in the final analysis, cannot be construed otherwise than openly joining the United States in its basic strategy aimed at freezing the division of Korea into ‘two Koreas,’ isolating us internationally and guiding us to ‘opening’ and thus overthrowing the socialist system in our country [….] However, our people will march forward, full of confidence in victory, without vacillation in any wind, under the unfurled banner of the Juche1 idea and defend their socialist position as an impregnable fortress.” 2 The Rodong Sinmun article quoted above was published in October 5, 1990, and was written as a response to the establishment of diplomatic relations between the Soviet Union, a critical ally for the North Korean regime, and South Korea, its archrival. The North Korean government’s main reactions to the changes taking place in the international environment during this time are illustrated clearly in this passage: fear of increased isolation, apprehension of external threats, and resistance to reform. The transformation of the international situation between the years of 1989 and 1992 presented a daunting challenge for the already struggling North Korean government. -

Marxism-Leninism in the History of North Korean Ideology, 1945-1989

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA Los Angeles From Soviet Origins to Chuch’e: Marxism-Leninism in the History of North Korean Ideology, 1945-1989 A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in Asian Languages and Cultures by Thomas Stock 2018 © Copyright by Thomas Stock 2018 ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION From Soviet Origins to Chuch’e: Marxism-Leninism in the History of North Korean Ideology, 1945-1989 by Thomas Stock Doctor of Philosophy in Asian Languages and Cultures University of California, Los Angeles, 2018 Professor Namhee Lee, Chair Where lie the origins of North Korean ideology? When, why, and to what extent did North Korea eventually pursue a path of ideological independence from Soviet Marxism- Leninism? Scholars typically answer these interrelated questions by referencing Korea’s historical legacies, such as Chosŏn period Confucianism, colonial subjugation, and Kim Il Sung’s guerrilla experience. The result is a rather localized understanding of North Korean ideology and its development, according to which North Korean ideology was rooted in native soil and, on the basis of this indigenousness, inevitably developed in contradistinction to Marxism-Leninism. Drawing on Eastern European archival materials and North Korean theoretical journals, the present study challenges our conventional views about North Korean ideology. Throughout the Cold War, North Korea was possessed by a world spirit, a Marxist- Leninist world spirit. Marxism-Leninism was North Korean ideology’s Promethean clay. From ii adherence to Soviet ideological leadership in the 1940s and 50s, to declarations of ideological independence in the 1960s, to the emergence of chuch’e philosophy in the 1970s and 80s, North Korea never severed its ties with the Marxist-Leninist tradition. -

Cahiers Du Cinema Spain

Cahiers du Cinéma Spain interview translation Interkosmos (2006), La Trinchera Lluminosa del Presidente Gonzalo (2007) and The Juche Idea (2008) form a trilogy with various points of view (always in the form of a fake documentary) about left-wing politics in the world. Was it planned as a trilogy from the origin? No. Interkosmos was originally going to be a 12-minute sequel to wüstenspringmaus, my short film about the history of the gerbil and the history of capitalism. Basically the idea that the guinea pig is a communist animal since it is so gentle and its only defense is in numbers. But I started developing this idea of a people’s carnival colony in space and then I needed humans and then a space capsule and so for two years I worked on Interkosmos until it became my first feature film. La Trinchera Luminosa del Presidente Gonzalo was in some ways a reaction to Interkosmos. I wanted to make something more serious in a way. And with the success of Interkosmos I was getting all kinds of advice about what kind of film to make and how to work with a producer. I had been interested in the seeming contradiction between the extreme violence and authoritarian qualities of the Shining Path and the fact that it had the highest proportion of women commanders of any Latin American guerrilla group in history. Shooting a kind of found video of that group made the most sense to me. For The Juche Idea, I was drawn to the subject by the visual splendor of the Mass Games and then I started researching the role of propaganda in the country and Kim Jong Il’s film theories and I was hooked. -

University of California Riverside

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA RIVERSIDE North Korean Literature: Margins of Writing Memory, Gender, and Sexuality A Dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Comparative Literature by Immanuel J Kim June 2012 Dissertation Committee: Professor Kelly Jeong, Chairperson Professor Annmaria Shimabuku Professor Perry Link Copyright by Immanuel J Kim 2012 The Dissertation of Immanuel J Kim is approved: _______________________________________ _______________________________________ _______________________________________ Committee Chairperson University of California, Riverside Acknowledgements First and foremost, I would like to thank the Korea Foundation for funding my field research to Korea from March 2010 to December 2010, and then granting me the Graduate Studies Fellowship for the academic year of 2011-2012. It would not be an overstatement for me to say that Korea Foundation has enabled me to begin and complete my dissertation. I would also like to thank Academy of Korean Studies for providing the funds to extend my stay in Korea. I am grateful for my advisors Professors Kelly Jeong, Henk Maier, and Annmaria Shimabuku, who have provided their invaluable comments and criticisms to improve and reshape my attitude and understanding of North Korean literature. I am indebted to Prof. Perry Link for encouraging me and helping me understand the similarities and differences found in the PRC and the DPRK. Prof. Kim Chae-yong has been my mentor in reading North Korean literature, opening up opportunities for me to conduct research in Korea and guiding me through each of the readings. Without him, my research could not have gotten to where it is today. Ch’oe Chin-i and the Imjingang Team have become an invaluable resource to my research of writers in the Writer’s Union and the dynamic changes occurring in North Korea today. -

Cold War Cultures in Korea by Travis Workman

Cold War Cultures in Korea Instructor: Travis Workman Campuses: U of Minnesota, Ohio State U, and Pennsylvania State U Course website: http://coldwarculturesinkorea.com In this course we will analyze the Cold War (1945-1989) not only as an era in geopolitics, but also as a historical period marked by specific cultural and artistic forms. We focus on the Korean peninsula, looking closely at the literary and film cultures of both South Korea and North Korea. We discuss how the global conflict between U.S.- centered and Soviet-centered societies affected the politics, culture, and geography of Korea between 1945 and 1989, treating the division of Korea as an exemplary case extending from the origins of the Cold War to the present. We span the Cold War divide to compare the culture and politics of the South and the North through various cultural forms, including anti-communist and socialist realist films, biography and autobiography, fiction, and political discourse. We also discuss the legacy of the Cold War in contemporary culture and in the continued existence of two states on the Korean peninsula. The primary purpose is to be able to analyze post-1945 Korean cultures in both their locality and as significant aspects of the global Cold War era. Topics will include the politics of melodrama, cinema and the body, visualizing historical memory, culture under dictatorship, and issues of gender. TEXTS For Korean texts and films, the writer or director’s family name appears first. Please use the family name in your essays and check with me if you are unsure. -

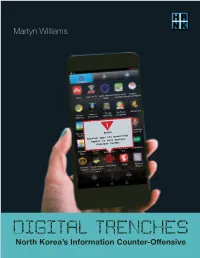

Digital Trenches

Martyn Williams H R N K Attack Mirae Wi-Fi Family Medicine Healthy Food Korean Basics Handbook Medicinal Recipes Picture Memory I Can Be My Travel Weather 2.0 Matching Competition Gifted Too Companion ! Agricultural Stone Magnolia Escpe from Mount Baekdu Weather Remover ERRORTelevision the Labyrinth Series 1.25 Foreign apps not permitted. Report to your nearest inminban leader. Business Number Practical App Store E-Bookstore Apps Tower Beauty Skills 2.0 Chosun Great Chosun Global News KCNA Battle of Cuisine Dictionary of Wisdom Terms DIGITAL TRENCHES North Korea’s Information Counter-Offensive DIGITAL TRENCHES North Korea’s Information Counter-Offensive Copyright © 2019 Committee for Human Rights in North Korea Printed in the United States of America All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, distributed, or transmitted in any form or by any means, including photocopying, recording, or other electronic or mechanical methods, without the prior permission of the Committee for Human Rights in North Korea, except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical reviews and certain other noncommercial uses permitted by copyright law. Committee for Human Rights in North Korea 1001 Connecticut Avenue, NW, Suite 435 Washington, DC 20036 P: (202) 499-7970 www.hrnk.org Print ISBN: 978-0-9995358-7-5 Digital ISBN: 978-0-9995358-8-2 Library of Congress Control Number: 2019919723 Cover translations by Julie Kim, HRNK Research Intern. BOARD OF DIRECTORS Gordon Flake, Co-Chair Katrina Lantos Swett, Co-Chair John Despres, -

Korean Reunification: the Dream and the Reality

KOREAN REUNIFICATION: THE DREAM AND THE REALITY CHARLES S. LEE Conventional wisdom, both Korean and non-Korean, assumis the division of this strategicpeninsula to be temporary. Officially, the Korean War still has not ended but is in a state of armistice. Popular belief also accepts as true that the greatest obstacles to Korean reunification are the East-West rivalry and the balance of power in the North Pacific. Charles S..Lee, however, argues that domestic conditions in North and South Korea actually present the more serious hurdle - a hurdle unlikely to be disposed of too quickly. INTRODUCTION Talk of reunifying the Korean peninsula once again is grabbing headlines. Catalyzed by the South Korean student movement's search for a new issue, the months surrounding the 1988 Summer Olympic Games in Seoul featured a flurry of unofficial and official initiatives on reunification. The students were quick to seize this emotionally charged issue as their new rallying cry, for the nation's recent democratic reforms (including a direct and seemingly fair presidential election in 1987) effectively deprived them of their raison d'etre. By June last year, thousands of them were on the march to the border village 6f Pahmunjom for a "summit" meeting with their North Korean counterparts. Not to be upstaged, the South Korean government blocked the marchers with tear gas, and on July 7, announced a sweeping set of proposals for improving North-South relations, including the opening of trade between the two Koreas. Capping last summer's events was South Korean President Roh Tae Woo's October speech at the UN General Assembly, in which he called for his own summit meeting with North Korean President Kim II Sung. -

![On Eliminating Dogmatism and Formalism and Establishing Juche [Chuch'e] in Ideological Work](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/0498/on-eliminating-dogmatism-and-formalism-and-establishing-juche-chuche-in-ideological-work-900498.webp)

On Eliminating Dogmatism and Formalism and Establishing Juche [Chuch'e] in Ideological Work

Primary Source Document with Questions (DBQs) “ON ELIMINATING DOGMATISM AND FORMALISM AND ESTABLISHING JUCHE [CHUCH’E] IN IDEOLOGICAL WORK” (SPEECH, 1955) By Kim Ilsŏng Introduction After the end of colonial rule in 1945, political divisions within Korea interacted with the escalating Cold War tension between the United States and USSR, each of which had occupied and fostered a government in one half of the peninsula, to create the conditions that led to the Korean War (1950‐53). In the aftermath of that war, with its non‐decisive result, the separation of North and South Korean states (officially the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea and the Republic of Korea, respectively) has been maintained to this day, continually reproduced until fairly recently by an atmosphere of mutual hostility. The Kim Ilsŏng (1912‐1994) government of the North considered itself the heir of the Communist anti‐imperialist struggle against Japanese forces in Manchuria. As time passed, other ideological foci came to supplement or even supplant Marxism‐Leninism as the central official state ideology. In this 1955 speech, entitled “On Eliminating Dogmatism and Formalism and Establishing Juche in Ideological Work,” Kim explained what he meant by juche (“subjectivity” in literal translation) and why it was important for North Korea. Document Excerpts with Questions (Longer selection follows this section) From Sources of Korean Tradition, edited by Yŏng‐ho Ch’oe, Peter H. Lee, and Wm. Theodore de Bary, vol. 2 (New York: Columbia University Press, 2000), 420‐424. © 2000 Columbia University Press. Reproduced with the permission of the publisher. All rights reserved. “On Eliminating Dogmatism and Formalism and Establishing Juche [Chuch’e] in Ideological Work” (Speech, 1955) By Kim Ilsŏng … It is important in our work to grasp revolutionary truth, Marxist‑Leninist truth, and apply it correctly to our actual conditions. -

North Korean Mass Games and Third Worldism in Guyana, 1980-1992 「鍛錬 された民のみぞ国づくりに役立つ」ガイアナにおける北朝鮮のマスゲー ムと第三世界主義 1980-1992

Volume 13 | Issue 4 | Number 2 | Article ID 4258 | Jan 26, 2015 The Asia-Pacific Journal | Japan Focus 'Only a disciplined people can build a nation': North Korean Mass Games and Third Worldism in Guyana, 1980-1992 「鍛錬 された民のみぞ国づくりに役立つ」ガイアナにおける北朝鮮のマスゲー ムと第三世界主義 1980-1992 Moe Taylor Abstract: As the 1970s drew to a close, Forbes appealing to a certain widespread longing Burnham (1923-85), Guyana's controversial within Guyanese culture for a more leader of 21 years, received Pyongyang's "disciplined" society. assistance in importing the North Korean tradition of Mass Games, establishing them as a major facet of the nation's cultural and political life during the 1980-92 period. The Introduction current study documents this episode in In the final months of 1979, while the Iran Guyanese history and seeks to explain why the hostage crisis and the Soviet invasion of Burnham regime prioritized such an Afghanistan dominated international headlines, experiment in a time of austerity and crisis, its the approximately 750,000 citizens of the South ideological foundations, and how Guyanese American republic of Guyana (formerly British interpreted and responded to Mass Games. Guiana) were informed by state-owned media I argue that the Burnham regime's enthusiasm about the coming arrival of a strange and for Mass Games can in large part be explained mysterious new thing called Mass Games, a by their adherence to a particular tradition of spectacle event that would be, according to one socialist thought which holds education and editorial, "the most magnificent in the history 1 culture as the foundation of development. -

Militaristic Propaganda in the DPRK the Heritage of Songun-Politics in the Rodong-Sinmun Under Kim Jong-Un

University of Twente Faculty of Behavioural, Management & Social Sciences 1st Supervisor: Dr. Minna van Gerven-Haanpaa Westfälische Wilhelms-Universität Münster Institut für Politikwissenschaft 2nd Supervisor: Björn Goldstein, M.A. Militaristic propaganda in the DPRK The heritage of Songun-Politics in the Rodong-Sinmun under Kim Jong-Un Julian Muhs Matr.- Nr.: 384990 B.A. & B.Sc Schorlemerstraße 4 StudentID; s1610325 Public Administration 48143 Münster (Westf.) (Special Emphasis on European Studies) 004915141901095 [email protected] Date: 21st of September.2015 Table of Contents 1. Introduction ..................................................................................................................................... 1 2. Theoretical Framework ................................................................................................................... 3 3.1. North Korean Ideology from Marxism-Leninism to Juche ........................................................... 3 3.2. Press Theory between Marxism-Leninism and Juche .................................................................. 8 3. Methodology ................................................................................................................................. 13 3.1. Selection of Articles .................................................................................................................... 17 4. Analysis: Military propaganda in the Rodong-Sinmun .................................................................. 19 4.1. Category-system