'March 2019' Issue In

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Complete List of Books in Library Acc No Author Title of Book Subject Publisher Year R.No

Complete List of Books in Library Acc No Author Title of book Subject Publisher Year R.No. 1 Satkari Mookerjee The Jaina Philosophy of PHIL Bharat Jaina Parisat 8/A1 Non-Absolutism 3 Swami Nikilananda Ramakrishna PER/BIO Rider & Co. 17/B2 4 Selwyn Gurney Champion Readings From World ECO `Watts & Co., London 14/B2 & Dorothy Short Religion 6 Bhupendra Datta Swami Vivekananda PER/BIO Nababharat Pub., 17/A3 Calcutta 7 H.D. Lewis The Principal Upanisads PHIL George Allen & Unwin 8/A1 14 Jawaherlal Nehru Buddhist Texts PHIL Bruno Cassirer 8/A1 15 Bhagwat Saran Women In Rgveda PHIL Nada Kishore & Bros., 8/A1 Benares. 15 Bhagwat Saran Upadhya Women in Rgveda LIT 9/B1 16 A.P. Karmarkar The Religions of India PHIL Mira Publishing Lonavla 8/A1 House 17 Shri Krishna Menon Atma-Darshan PHIL Sri Vidya Samiti 8/A1 Atmananda 20 Henri de Lubac S.J. Aspects of Budhism PHIL sheed & ward 8/A1 21 J.M. Sanyal The Shrimad Bhagabatam PHIL Dhirendra Nath Bose 8/A2 22 J.M. Sanyal The Shrimad PHIL Oriental Pub. 8/A2 Bhagabatam VolI 23 J.M. Sanyal The Shrimad PHIL Oriental Pub. 8/A2 Bhagabatam Vo.l III 24 J.M. Sanyal The Shrimad Bhagabatam PHIL Oriental Pub. 8/A2 25 J.M. Sanyal The Shrimad PHIL Oriental Pub. 8/A2 Bhagabatam Vol.V 26 Mahadev Desai The Gospel of Selfless G/REL Navijvan Press 14/B2 Action 28 Shankar Shankar's Children Art FIC/NOV Yamuna Shankar 2/A2 Number Volume 28 29 Nil The Adyar Library Bulletin LIT The Adyar Library and 9/B2 Research Centre 30 Fraser & Edwards Life And Teaching of PER/BIO Christian Literature 17/A3 Tukaram Society for India 40 Monier Williams Hinduism PHIL Susil Gupta (India) Ltd. -

03 Reviews of Literature.Pdf

REVIEWS OF THE RELATED LITERATURE While reading thesis, books and journals I have got reviews from the other scholars who have worked on major Indian literature. Malik,(2013) from the centre for comparative study of Indian Languages and cultural, Aligahrdh Muslim University has presented a paper in Asian journal of social science and humanities under the title “Cultural and Linguistic issues in Translation of fiction with special reference to Amin Kamil‟s short story The Cock Fight. This paper is based on the translation of a collection of stories “ Kashmiri Short stories.” He has chosen story The Cock fight .It is translated by M.S. Beigh. He wants to focus that translation process of the linguistic and cultural issues encountered in the original and how they were resolved in translation. Tamilselvi,(2013) Assistant professor of English ,at SFR college at Tamilnadu has written a paper in Criterion journal under the title; “ Depiction of Parsi World –view in selected Short Stories of Rohinton Mistry‟s Tales from Firozha Baag”(2013) The paper focuses on Rohan Mistry‟s experiences as a minority status. She illustrates how Mistry has depicted the life of Parsis their customs in the stories. He also records Parsi‟s social circumstances ,sense of isolation and ruthlessness ,tie them to gather and make them forge a bond of understanding as they struggle to survive. Roy,(2012) assistant professor in Karim city College, Jameshedpur has written an article in Criterion Journal under the title Re- Inscribing the mother within motherhood : A Feminist Reading of Shauna Singh Baldwin‟s Short Story Naina The paper examines to look at Naina‟s experience of motherhood as a deconstruction of the patriarchal maternity narrative and attempt to reclaim the subject-position of the mother through Dependence/Independence of motherhood from the father paternal authority on the material subject Mother-daughter relationship and linking Gestation and creativity . -

Women at Crossroads: Multi- Disciplinary Perspectives’

ISSN 2395-4396 (Online) National Seminar on ‘Women at Crossroads: Multi- disciplinary Perspectives’ Publication Partner: IJARIIE ORGANISE BY: DEPARTMENT OF ENGLISH PSGR KRISHNAMMAL COLLEGE FOR WOMEN, PEELAMEDU, COIMBATORE Volume-2, Issue-6, 2017 Vol-2 Issue-6 2017 IJARIIE-ISSN (O)-2395-4396 A Comparative Study of the Role of Women in New Generation Malayalam Films and Serials Jibin Francis Research Scholar Department of English PSG College of Arts and Science, Coimbatore Abstract This 21st century is called the era of technology, which witnesses revolutionary developments in every aspect of life. The life style of the 21st century people is very different; their attitude and culture have changed .This change of viewpoint is visible in every field of life including Film and television. Nowadays there are several realty shows capturing the attention of the people. The electronic media influence the mind of people. Different television programs target different categories of people .For example the cartoon programs target kids; the realty shows target youth. The points of view of the directors and audience are changing in the modern era. In earlier time, women had only a decorative role in the films. Their representation was merely for satisfying the needs of men. The roles of women were always under the norms and rules of the patriarchal society. They were most often presented on the screen as sexual objects .Here women were abused twice, first by the male character in the film and second, by the spectators. But now the scenario is different. The viewpoint of the directors as well as the audience has drastically changed .In this era the directors are courageous enough to make films with women as central characters. -

Towards an Alternative Indian Poetry Akshaya K. Rath

Towards an Alternative Indian Poetry Akshaya K. Rath One of the debates that has kept literary scholars of the present generation engaged and has ample implication for teaching pedagogy is the problem of canon-formation in Indian English poetry. One of the ways in which such canon- making operates is through the compilation, use and importance of anthologies. Anthology making is a conscious political act that sanctions a poet or poem its literary status. It has given rise to the publication of numerous anthologies in the Indian scenario and in the recent decades we have witnessed the emergence of a handful of alternative anthologies. Anthologies in general remain compact; they are convenient and often less expensive than purchasing separate texts. Those are some of the reasons for their popularity. However, as the case has been, inclusion of a poet or poem is hardly an innocent phenomenon. We have witnessed that canonical anthologies in India are exclusive about their selection of poets and poems, and in most cases the editor‘s profession remains central to anthology making. Hence, there is a need to address the issue of anthology making in Indian scenario that decides the future of poetry/poets in India. This paper explores the historiography of anthology making in India in the light of the great Indian language debate put forward by Buddhadeva Bose. It also highlights that there a significant transition in the subject of canon-formation at the turn of the century with the rise of an alternative canon. The politics of inclusion and exclusion—of anthologizing and publishing Indian English poetry—will be central to the discussion of anthologizing alternative Indian English poetry. -

Arundhati Roy and New Inscription on Autumn Leaves Nazia Hassan

Running Head: ARUNDHATI ROY AND NEW INSCRIPTION ON AUTUMN LEAVES 74 8ICLICE 2017-111 Nazia Hasan Arundhati Roy and New Inscription on Autumn Leaves Nazia Hassan Aligarh Muslim University India [email protected] Abstract New writings hold new truths and new hopes, as well. Arundhati Roy proves that once more. The God of Small things to The Ministry of Utmost Happiness weave an India and the world from North to South, from little joys to big agonies, small acts to huge rewards, grand shows to petty hearts…She once again speaks of the subalterns, the subjugated, the dismissed and the obliterated, the blinds and the hide-outs how the fists of resistance do not come down, the wish for rights, the dreams for dignity do not dim even as they bleed and endure like trees would treat witherings and autumns. Her works speak of high born ‘laltains’, the low born ‘mombatties’, the nowhere persons called eunuchs, orphans and the disowned; while worrying over drying river beds, dying birds and poachings rampant: she at least, wakes one up to the world! That’s the new writing which gives space to the unsaid and sheds light on the unrevealed. The history house doors are opened, the worm cans of Kasmir Military camps and Militant hide outs which indulge in something similar, the difference being the intention only which is a hair line one. We hear Dickens to Spivak in these new inscriptions. If Aftab is Anjum, then Anjum is the people called India, people called the world who are divided over caste, class, colour and deformity which no person inflicts on oneself. -

American College Journal of English Language and Literature (Acjell) No

American College Journal of English Language and Literature (acjell) no. 4 ISSN: 1725 2278 876X 2015 Research Department of English The American College Madurai, Tamilnadu, India American College Journal of English Language and Literature (acjell) no. 4 ISSN: 1725 2278 876X 2015 Research Department of English The American College Madurai, Tamilnadu, India © acjell 2015 the american college journal of english language and literature is published annually. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced in any form and by any means without prior permission from: The Editor, ACJELL, Postgraduate and Research Department of English, The American College, Madurai, Tamilnadu, India. Email: [email protected] ISSN: 1725 2278 876X annual subscription— International: US $ 50 | India: Rs.1000 Cheques/ Demand Drafts may be made from any nationalised bank in favour of “The Editor, ACJELL” Research Department of English, The American College, payable at Madurai. Publisher: Research Department of English The American College, Madurai 625 002 Design and Production: +G Publishing, Madurai | Bangalore E-mail: [email protected] | www.plusgpublishing.com 04 Vol. No. 3 | March 2015 Editorial Board Dr. J. John Sekar, Editor-in-chief Head, Research Department of English Dean, Academic Policies & Administration The American College Editors Dr. S. Stanley Mohandoss Stephen Visiting Professor Research Department of English, The American College Dr. G. Dominic Savio Visiting Professor Research Department of English, The American College Dr. Francis Jarman Hildesheim University, Germany Dr. J. Sundarsingh Head, Department of English Karunya University, Coimbatore Dr. J. Rajakumar Associate Professor Research Department of English, The American College Dr. M. Lawrence Assistant Professor Research Department of English, The American College Dr. -

Euphoria of Renovation from Cultural Amalgamation in Bharati Mukherjee’S the Holder of the World

======================================================================= Language in India www.languageinindia.com ISSN 1930-2940 Vol. 19:4 April 2019 India’s Higher Education Authority UGC Approved List of Journals Serial Number 49042 ==================================================================== Euphoria of Renovation from Cultural Amalgamation in Bharati Mukherjee’s The Holder Of The World Dr. M. Mythili Associate Professor Department of English Nandha Engineering College (Autonomous) Erode, Tamilnadu-638052, India [email protected] ======================================================================== Abstract Bharati Mukherjee, a trailblazer of diaspora in North America, is an established novelist of the post-modern era. She is one of the prominent diasporic women novelists who mainly focus on female protagonists in their novels. Mukherjee strongly believes that a genuine fiction should epitomize the emotional, intellectual and physical responses of the characters when they are caught in a situation which is strange to them. Her protagonists are projected as individuals who have the potentiality to face the bitter truth of their lives as immigrants, but do not fall prey to the circumstances; rather they are brave enough to accustom themselves in the new environment. They are presented as paragons of vigour and valour to wrestle with the problems of life for the sake of survival. Mukherjee's protagonists leave a long lasting influence on readers’ mind as they finally emerge out as successful beings in their adopted land. The fiction, The Holder of the World, is an ideal unification of the past and the present where the author traces the story of Hannah Easton, a New Englander, who was ultimately deemed as the mistress to an Indian Emperor. The novel exposes the change in geographical and cultural space - from America to India through England, and as a result of which the young protagonist renovates herself. -

Bombay Modern: Arun Kolatkar and Bilingual Literary Culture

Postcolonial Text, Vol 12, No 3 & 4 (2017) Bombay Modern: Arun Kolatkar and Bilingual Literary Culture Anjali Nerlekar 292 pages, 2016, $99.95 USD (hardcover), $34.95 USD (paperback), $34.95 USD (e-book) Northwestern University Press Reviewed by Graziano Krätli, Yale University Anjali Nerlekar’s Bombay Modern is the second book-length study of the Indian poet Arun Kolatkar (1931-2004) to be published within the past couple of years, coming right after Laetitia Zecchini’s Arun Kolatkar and Literary Modernism in India (2014). The two scholars worked independently yet in awareness of each other’s research, which resulted in two books that are distinct and complementary, and equally indispensable to a better understanding of Indian poetic culture in postcolonial Bombay and beyond. Kolatkar is the quintessential posthumous poet. Wary of intercourse with commercial publishers and media in general, he carefully and selectively cultivated the art of reclusion, avoiding all kinds of publicity, shying away from interviews, and publishing very little in his lifetime. Only after he was diagnosed with terminal cancer, and largely thanks to the encouragement of friends - especially the poets Adil Jussawalla and Arvind Krishna Mehrotra, and the publisher Ashok Shahane - did he agree to the publication of two collections, Kala Ghoda Poems and Sarpa Satra, not long before he died in September 2004. These were followed by the New York Review of Books edition of Jejuri (2005); Arun Kolatkarchya Char Kavita (2006; a reprint of four Marathi poems originally published in 1977), and The Boatride & Other Poems (2009), both published by Pras Prakashan. The latter was edited by Mehrotra, who is also responsible for Collected Poems in English (Bloodaxe, 2010), and the forthcoming Early Poems and Fragments (Pras Prakashan). -

Bharathipura” K.Rukmani Viji & M.Sinthiya

Vol. 7 Special Issue 1 July, 2019 Impact Factor: 4.110 ISSN: 2320-2645 One Day National Level Seminar Contemporary Discourses in English Studies th 30 July, 2019 Special Issue Editors Mr. R. Kannadass Mr. P. Sridharan DEPARTMENT OF ENGLISH MORAPPUR KONGU COLLEGE OF ARTS AND SCIENCE (Affiliated to Periyar University, Salem-11) Kongu Nagar, Krishnagiri Main Road, Morappur-635 305, Dharmapuri (Dt) Web: www.morappurkonguarts.com Contact No: 04346 263201, 9487655338 MORAPPUR KONGU COLLEGE OF ARTS AND SCIENCE (Affiliated to Periyar University, Salem-11) Kongu Nagar, Krishnagiri Main Road, Morappur-635 305, Dharmapuri (Dt). Phone: 04346 263201, 9487655338 Web: www.morappurkonguarts.com Thiru. C. Muthu, Chairman Kongu Educational Trust CHAIRMAN MESSAGE “Savings is an important tool because it can help the poor deal with the ups and downs of irregular earnings and help them build reserves for a rainy day” It provides huge pleasure to notice that the Department of English is organizing the National seminar on 30th July 2019 at Morappur Kongu College of Arts and Science within idea of “Contemporary Discourses in English Studies” during this conference vast range of legendary college and professionals would share vital themes of the conference. I assure that the Department of English can keep it up doing their works as excellent and build our college to proud and I wish for their future Endeavour’s. I would like to congratulate the PG & Research Department of English, the organizers for having chosen the right topic on right time. MORAPPUR KONGU COLLEGE OF ARTS AND SCIENCE (Affiliated to Periyar University, Salem-11) Kongu Nagar, Krishnagiri Main Road, Morappur-635 305, Dharmapuri (Dt). -

BLOGS Dow Shalt Pay for Bhopal Just for the Record, and Those

BLOGS Dow Shalt Pay For Bhopal Just for the record, and those who missed it earlier, thanks to a revival on Twitter -- and perhaps because of that the resulting emails today -- of the old Yes Men hoax/prank on BBC. The Yes Men explain the background: Dow claims the company inherited no liabilities for the Bhopal disaster, but the victims aren't buying it, and have continued to fight Dow just as hard as they fought Union Carbide. That's a heavy cross to bear for a multinational company; perhaps it's no wonder Dow can't quite face the truth. The Yes Men decided, in November 2002, to help them do so by explaining exactly why Dow can't do anything for the Bhopalis: they aren't shareholders. Dow responded in a masterfully clumsy way, resulting in a flurry of press. Two years later, in late November 2004, an invitation arrived at the 2002 website, neglected since. On the 20th anniversary of the Bhopal disaster, "Dow representative" "Jude Finisterra" went on BBC World TV to announce that the company was finally going to compensate the victims and clean up the mess in Bhopal. The story shot around the world, much to the chagrin of Dow, who briefly disavowed any responsibility as per policy. The Yes Men again helped Dow be clearer about their feelings. (See also this account, complete with a story of censorship.) Only months after Andy's face had been on most UK tellies, he appeared at a London banking conference as Dow rep "Erastus Hamm," this time to explain how Dow considers death acceptable so long as profits still roll in. -

Mapping the Cultural Landscape of Indian English Poetry

International Journal of Scientific & Innovative Research Studies ISSN : 2347-7660 (Print) | ISSN : 2454-1818 (Online) MAPPING THE CULTURAL LANDSCAPE OF INDIAN ENGLISH POETRY Dr. Vipin Singh Chauhan, Assistant Professor, Department of English, Sri Aurobindo College (Evening), University of Delhi. ABSTRACT The Paper “Mapping the Cultural Landscape of Indian English Poetry” is an attempt to critically look at the major Indian English poets starting from the early nineteenth century. The paper traces the poets and their contribution along with their cultural response to the ways in which Indian nation responds to the colonial rule and to the emergence of English as a language in India. All the major poets of the Indian English tradition are being touched upon to explore their cultural response as well as to understand the ways what trajectory Indian English poetry took in its journey of about two hundred years. Key Words: British, Colonial, Gandhi, Indian English, New Poetry, Poetry, Post Colonial, Post- independence poets. Indian English literature happened in India as a May come refined with th’ accents that are ours. byproduct of the British colonial rule for about two (Samuel Daniel, quoted in Naik, History, 1) hundred years. It can be said that Indian English, and Literature concerned with it, is a cultural impact of Samuel Daniel’s prophecy to some extent has come the colonial forces. As the British colonized other true as Indian English literature today exists as a parts of the world, the spread and impact of English distinct identity and flourishes in the whole world. Language can be seen throughout the world where As for its title “Indian English Literature, probably it English language flourished in their own ways. -

September 2019

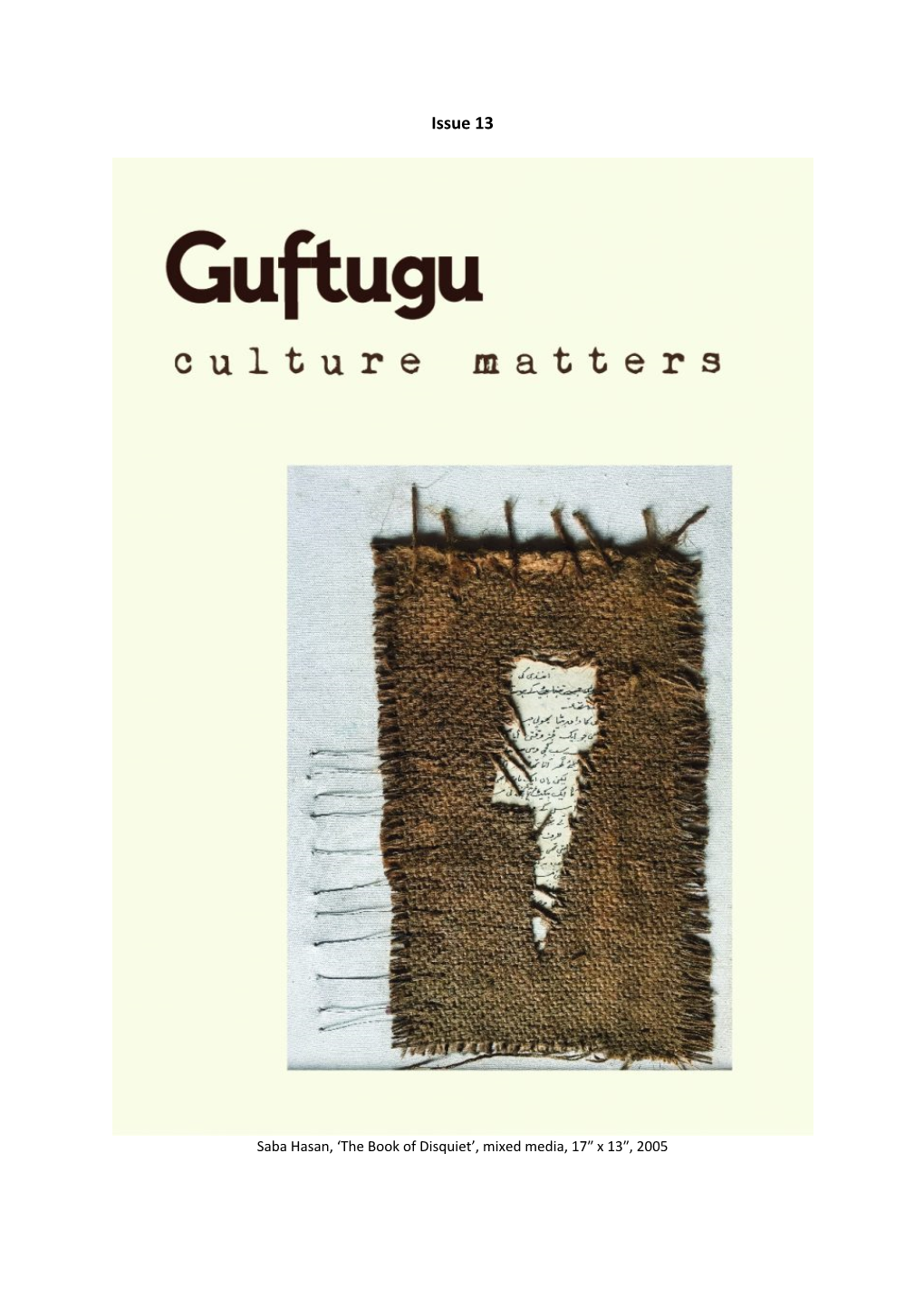

September 2019 Ranbir Kaleka, ‘Boy without Reflection’, oil on canvas, 305x152cm, 2004 About Us Culture matters. And it has to matter in India, with its diverse languages, dialects, regions and communities; its rich range of voices from the mainstream and the peripheries. This was the starting point for Guftugu (www.guftugu.in), a quarterly e-journal of poetry, prose, conversations, images and videos which the Indian Writers’ Forum runs as one of its programmes. The aim of the journal is to publish, with universal access online, the best works by Indian cultural practitioners in a place where they need not fear intimidation or irrational censorship, or be excluded by the profit demands of the marketplace. Such an inclusive platform sparks lively dialogue on literary and artistic issues that demand discussion and debate. The guiding spirit of the journal is that culture must have many narratives from many different voices – from the established to the marginal, from the conventional to the deeply experimental. To sum up our vision: Whatever our language, genre or medium, we will freely use our imagination to produce what we see as meaningful for our times. We insist on our freedom to speak and debate without hindrance, both to each other and to our readers and audience. Together, but in different voices, we will interpret and reinterpret the past, our common legacy of contesting narratives; and debate on the present through our creative work. Past issues of Guftugu can be downloaded as PDFs. Downloads of issues are for private reading only. All material in Guftugu is copyrighted.