Yellowstone Grizzly Bear Investigations 2007

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Yellowstone Grizzly Bear Investigations 2008

Yellowstone Grizzly Bear Investigations 2008 Report of the Interagency Grizzly Bear Study Team Photo courtesy of Steve Ard Data contained in this report are preliminary and subject to change. Please obtain permission prior to citation. To give credit to authors, please cite the section within this report as a chapter in a book. Below is an example: Moody, D.S., K. Frey, and D. Meints. 2009. Trends in elk hunter numbers within the Primary Conservation Area plus the 10-mile perimeter area. Page 39 in C.C. Schwartz, M.A. Haroldson, and K. West, editors. Yellowstone grizzly bear investigations: annual report of the Interagency Grizzly Bear Study Team, 2008. U.S. Geological Survey, Bozeman, Montana, USA. Cover: Female #533 with her 3 3-year-old offspring after den emergence, taken 1 May 2008 by Steve Ard. YELLOWSTONE GRIZZLY BEAR INVESTIGATIONS Annual Report of the Interagency Grizzly Bear Study Team 2008 U.S. Geological Survey Wyoming Game and Fish Department National Park Service U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Montana Fish, Wildlife and Parks U.S. Forest Service Idaho Department of Fish and Game Edited by Charles C. Schwartz, Mark A. Haroldson, and Karrie West U.S. Department of the Interior U.S. Geological Survey 2009 Table of Contents INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................................................................. 1 This Report ............................................................................................................................................ -

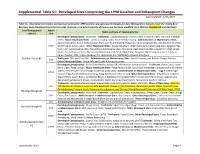

Supplemental Table S1: Developed Sites Comprising the 1998 Baseline and Subsequent Changes Last Updated: 3/31/2015

Supplemental Table S1: Developed Sites Comprising the 1998 Baseline and Subsequent Changes Last Updated: 3/31/2015 Table S1. Developed sites (name and type) comprising the 1998 baseline and subsequent changes per Bear Management Subunit inside the Grizzly Bear Recovery Zone (Developed sites that are new, removed, or in which capacity of human-use has been modified since 1998 are highlighted and italicized). Bear Management Admin Name and type of developed sites subunit Unit Developed Campgrounds: Cave Falls. Trailheads: Coyote Meadows, Hominy Peak, S. Boone Creek, Fish Lake, Cascade Creek. Major Developed Sites: Loll Scout Camp, Idaho Youth Services Camp. Administrative or Maintenance Sites: Squirrel Meadows Guard Station/Cabin, Porcupine Guard Station, Badger Creek Seismograph Site, and Squirrel Meadows CTNF GS/WY Game & Fish Cabin. Other Developed Sites: Grassy Lake Dam, Tillery Lake Dam, Indian Lake Dam, Bergman Res. Dam, Loon Lake Disperse sites, Horseshoe Lake Disperse sites, Porcupine Creek Disperse sites, Gravel Pit/Target Range, Boone Creek Disperse Sites, Tillery Lake O&G Camp, Calf Creek O&G Camp, Bergman O&G Camp, Granite Creek Cow Camp, Poacher’s TH, Indian Meadows TH, McRenolds Res. TH/Wildlife Viewing Area/Dam. Bechler/Teton #1 Trailheads: 9K1 and Cave Falls. Administrative or Maintenance Sites: South Entrance and Bechler Ranger Stations. YNP Other Developed Sites: Union Falls and Snake River picnic areas. Developed Campgrounds: Grassy Lake Road campsites (8 individual car camping sites). Trailheads: Glade Creek, Lower Berry Creek, Flagg Canyon. Major Developed Sites: Flagg Ranch (lodge, cabins and Headwater Campground with camper cabins, remote cistern and sewage treatment plant sites). Administrative or Maintenance Sites: Flagg Ranch Ranger GTNP Station, Flagg Ranch employee housing, Flagg Ranch maintenance yard. -

2021 Adventure Vacation Guide Cody Yellowstone Adventure Vacation Guide 3

2021 ADVENTURE VACATION GUIDE CODY YELLOWSTONE ADVENTURE VACATION GUIDE 3 WELCOME TO THE GREAT AMERICAN ADVENTURE. The West isn’t just a direction. It’s not just a mark on a map or a point on a compass. The West is our heritage and our soul. It’s our parents and our grandparents. It’s the explorers and trailblazers and outlaws who came before us. And the proud people who were here before them. It’s the adventurous spirit that forged the American character. It’s wide-open spaces that dare us to dream audacious dreams. And grand mountains that make us feel smaller and bigger all at the same time. It’s a thump in your chest the first time you stand face to face with a buffalo. And a swelling of pride that a place like this still exists. It’s everything great about America. And it still flows through our veins. Some people say it’s vanishing. But we say it never will. It will live as long as there are people who still live by its code and safeguard its wonders. It will live as long as there are places like Yellowstone and towns like Cody, Wyoming. Because we are blood brothers, Yellowstone and Cody. One and the same. This is where the Great American Adventure calls home. And if you listen closely, you can hear it calling you. 4 CODYYELLOWSTONE.ORG CODY YELLOWSTONE ADVENTURE VACATION GUIDE 5 William F. “Buffalo Bill” Cody with eight Native American members of the cast of Buffalo Bill’s Wild West Show, HISTORY ca. -

Foundation Document Overview Yellowstone National Park Wyoming, Montana, Idaho

NATIONAL PARK SERVICE • U.S. DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR Foundation Document Overview Yellowstone National Park Wyoming, Montana, Idaho Contact Information For more information about the Yellowstone National Park Foundation Document, contact: [email protected] or 307-344-7381 or write to: Superintendent, Yellowstone National Park, PO Box 168, Yellowstone National Park, WY 82190-0168 Park Description Yellowstone became the world’s first national park on March This vast landscape contains the headwaters of several major 1, 1872, set aside in recognition of its unique hydrothermal rivers. The Firehole and Gibbon rivers unite to form the Madison, features and for the benefit and enjoyment of the people. which, along with the Gallatin River, joins the Jefferson to With this landmark decision, the United States Congress create the Missouri River several miles north of the park. The created a path for future parks within this country and Yellowstone River is a major tributary of the Missouri, which around the world; Yellowstone still serves as a global then flows via the Mississippi to the Gulf of Mexico. The Snake resource conservation and tourism model for public land River arises near the park’s south boundary and joins the management. Yellowstone is perhaps most well-known for its Columbia to flow into the Pacific. Yellowstone Lake is the largest hydrothermal features such as the iconic Old Faithful geyser. lake at high altitude in North America and the Lower Yellowstone The park encompasses 2.25 million acres, or 3,472 square Falls is the highest of more than 40 named waterfalls in the park. miles, of a landscape punctuated by steaming pools, bubbling mudpots, spewing geysers, and colorful volcanic soils. -

Biological Evaluation R2-02-03

BIOLOGICAL EVALUATION R2-02-03 EVALUATION OF DOUGLAS-FIR BEETLE ALONG THE NORTH FORK OF THE SHOSHONE RIVER, SHOSHONE NATIONAL FOREST, WYOMING JANUARY 2002 PREPARED BY:_/S/ KURT ALLEN_________________________________ Kurt K. Allen Entomologist Rapid City Service Center PREPARED BY:__/s/ Dan Long __________________________________ Daniel F. Long Forest Health Technician Rapid City Service Center APPROVED BY:___/s/ Frank Cross _______________________________ Frank J. Cross Group Leader Forest Health Management Renewable Resources USDA Forest Service Rocky Mountain Region 740 Simms Street Golden, CO 80401 ABSTRACT Douglas-fir beetle (Dendroctonus pseudotsugae) infestations frequently result from disturbance events that create large volumes of weakened Douglas-fir (Pseudotsuga menziesii) trees. In 1988, extensive wildfires occurred in Yellowstone National Park and the Shoshone National Forest. Populations of Douglas-fir beetle increased in fire-scorched trees caused by the wildfires. Subsequent generations of the beetles moved from these injured trees to undamaged trees in neighboring stands on the Shoshone National Forest, Wyoming. This outbreak has now moved and is concentrated along the North Fork of the Shoshone River. Beetle populations continue to build and continued high levels of mortality can be expected along the North Fork. Continued use of sanitation harvest and anti-aggregation pheromones, where possible is recommended. 1 INTRODUCTION The Douglas-fir beetle (Dendroctonus pseudotsugae Hopkins) infests and kills Douglas-fir (Pseudotsuga menziesii) throughout its range in North America. Typically, the beetle reproduces in scattered trees that are highly stressed, such as windfall, defoliated or fire- scorched trees (Furniss, 1962; Furniss, 1965; Lessard and Schmid, 1990). If enough suitable host material is present, beetles can increase in the stressed trees and infest nearby healthy trees (Furniss et al., 1981). -

Red Star Lodge and Sawmill National Register Form Size

NPS Form 10-900 OMB No. 1024-0018 (Rev. 10-90) United States Department of the Interior National Park Service NATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES REGISTRATION FORM This form is for use in nominating or requesting determinations for individual properties and districts. See instructions in How to Complete the National Register of Historic Places Registration Form (National Register Bulletin 16A). Complete each item by marking "x" in the appropriate box or by entering the information requested. If any item does not apply to the property being documented, enter "N/A" for "not applicable." For functions, architectural classification, materials, and areas of significance, enter only categories and subcategories from the instructions. Place additional entries and narrative items on continuation sheets (NPS Form 10-900a). Use a typewriter, word processor, or computer, to complete all items. 1. Name of Property historic name: Red Star Lodge and Sawmill other names/site number: Shoshone Lodge 2. Location street & number: 349 Yellowstone Highway not for publication N/A city or town: Cody x vicinity state: Wyoming code: WY county: Park code: 29 zip code: 82414 3. State/Federal Agency Certification As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act of 1986, as amended, I hereby certify that this J(_ nomination __ request for determination of eligibility meets the documentation standards for registering properties in the National Register of Historic Places and meets the procedural and professional requirements set forth in 36 CFR Part 60. In my opinion, the property _>l meets __ does not meet the National Register Criteria. I recommend that this property be considered significant )C nationally __ statewide __ locally. -

Geological Evaluation of Infrared Imagery, Eastern Part of I 2 Yellowstone National Park, Wyoming and Montana I 3 by Ii I 4 I Harry W

General Disclaimer One or more of the Following Statements may affect this Document This document has been reproduced from the best copy furnished by the organizational source. It is being released in the interest of making available as much information as possible. This document may contain data, which exceeds the sheet parameters. It was furnished in this condition by the organizational source and is the best copy available. This document may contain tone-on-tone or color graphs, charts and/or pictures, which have been reproduced in black and white. This document is paginated as submitted by the original source. Portions of this document are not fully legible due to the historical nature of some of the material. However, it is the best reproduction available from the original submission. Produced by the NASA Center for Aerospace Information (CASI) ,,AT Qi I )^'--;fit,: JH J UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR Interagency Report NASA-83 GEOLOGICAL SURVEY '^'•a.YA ). tbo 1958 WASHINGTON. D.C. 20242 H69 $ (ACCESSION NUMI ("RU) Mr. Robert Porter a Acting Program Chief, (CODE) Earth Resources S^irvey Code SAR - NASA Headquarters W—CR OR TMX NUMBER) OR AD tGTE60RY) Washington, D.C. 20545 Dear Bob: Transm_tted herewith is one copy of: INTERAGENCY REPORT NASA-82 GEOLOGICAL EVALUATION OF INFRARED IKAGERY, EASTERN PART OF YELLOWSTONE NATIONAL PA%<, ViOtAING AND MONTANA* ^. by Harry W. Smedes** The U.S. Geological Survey has released this report in open files. Copies are available for consultation in the Geological Survey Libraries, 1033 GSA Building, Washington, D.C. 20242; Building 25, Federal Center, Danver, Colorado 80225; 345 Middlefield Road, Menlo ?ark, California 94025; and 601 E. -

2017 Experience Planner

2017 Experience Planner A Guide to Lodging, Camping, Dining, Shopping, Tours, and Activities in Yellowstone Don’t just see Yellowstone. Experience it. MAP LEGEND Contents LODGING Old Faithful Inn, Old Faithful Lodge Cabins, Old General Info 3 OF Must-Do Adventures 4 Faithful Snow Lodge & Cabins (pg 11-14) Visitor Centers & Park Programs 5 GV Grant Village Lodge (pg. 27-28) Visiting Yellowstone with Kids 6 Canyon Lodge & Cabins (pg 21-22) Tips for Summer Wildlife Viewing 9 CL 12 Awesome Day Hikes 19-20 LK Lake Yellowstone Hotel, Lake Lodge Cabins (pg 15-18) Photography Tips 23-24 M Mammoth Hot Springs Hotel & Cabins (pg 7-8) How to Travel Sustainably 29-30 Animals In The Park 33-34 RL Roosevelt Lodge (pg 25-26) Thermal Features 35-36 CAMPING Working in Yellowstone 43-44 (Xanterra-operated Campground) Partner Pages 45-46 Canyon, Madison, Bridge Bay, Winter Fishing Bridge RV Park, Grant Village (pg 31-32) Reasons to Visit in Winter 37-38 Winter Packages 39-40 DINING Winter Tours & Activities 41-42 Old Faithful Inn Dining Room, Bear Paw Deli, OF Obsidian Dining Room, Geyser Grill, Old Faithful Location Guides Lodge Cafeteria (pg 11-14) Grant Village Dining Room, Grant Village Lake House Mammoth Area 7-8 GV Old Faithful Area 11-14 (pg 27-28) Yellowstone Lake Area 15-18 Canyon Lodge Dining Room, Canyon Lodge Canyon Area 21-22 CL Roosevelt Area 25-26 Cafeteria, Canyon Lodge Deli (pg 21-22) Grant Village Area 27-28 Lake Yellowstone Hotel Dining Room, Lake Hotel LK Campground Info 31-32 Deli, Lake Lodge Cafeteria (pg 15-18) Mammoth Hot Springs Dining Room, Mammoth M Terrace Grill (pg 7-8) Roosevelt Lodge Dining Room. -

Thesis Winter Ecology of Bighorn Sheep In

THESIS WINTER ECOLOGY OF BIGHORN SHEEP IN YELLOWSTONE NATIONAL PARK Submitted by John L. 01demeyer In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of Master of Science Colorado State University December 1966 COLORADO STATE m~IVERSI1Y December 1966 WE HEREBY RECOl-lEEND 'lRAT lliE 'IHESIS PREPARED UNDER OUR SUPERVISION BY J onn L. 01demeyer ENTITLED tt'v-linter ecolo&;,( of bighorn sheep in yellowstone National ParkU BE ACCEPTED AS FULFILLING nus PART OF 'mE ~UIIill"LENTS FOR THE DillREE OF EASTER OF SCI~CE. CO:TJli ttee on Graduate Work --- - Examination Satisfacto~ Pennission to publish this thesis or any part of it must be obtained from the Dean of the Graduate School. PJL,ORADO STATE UN !VEKS ITY LI BRARIES i ABSTRACT WIN TER ECOLOOY OF ID:GHORN SHEEP IN YELLOVlS'IDHE NA TI ONAL PARK A bighorn sheep study was conducted on the northern winter range of yellowstone National Park, TNY01~inE from JIDle 1965 to June 1966. The objectives of the study were to census the bighorn population, map the winter bighorn distribution, detennine plant conposition and utilization on irnportant bighorn winter ranees, observe daily feedine habits, and assess the effect of competition on bighorn sheep. ~o hundred twen~ nine bighorn sheep wintered on the northern winter range. These herds were located on Nt. Everts, along the Yellowstone River, on Specimen Ridge, and along Soda Butte Creek. The ewe to ram ratio was 100: 78, the ewe to lamb ra tic waS 100: 47, and the ewe to yearling ratio was 100: 20. Range analysis was done on HacHinn Bench, Specimen Ridge, and Druid Peak. -

Yellowstone Wolf Project Annual Report 2004

Yellowstone Wolf Project Annual Report 2004 Douglas W. Smith, Daniel R. Stahler, and Debra S. Guernsey National Park Service Yellowstone Center for Resources Yellowstone National Park, Wyoming YCR-2005-02 Suggested citation: Smith, D.W., D.R. Stahler, and D.S. Guernsey. 2005. Yellowstone Wolf Project: Annual Report, 2004. National Park Service, Yellowstone Center for Resources, Yellowstone National Park, Wy o ming, YCR-2005-02. Wolf logo on cover and title page: Original illustration of wolf pup #47, born to #27, of the Nez Perce pack in 1996, by Melissa Saunders. Treatment and design by Renée Evanoff. All photos not otherwise marked are NPS photos by Douglas Smith and Daniel R. Stahler. ii TABLE OF CONTENTS Background .............................................................iv Gibbon Meadows Pack ........................................10 2004 Summary .........................................................v Bechler Pack ........................................................11 Territory Map ..........................................................vi Wolf Capture and Collaring ...................................11 The Yellowstone Wolf Pop u la tion .............................1 Wolf Predation ........................................................11 Population and Territory Status .............................1 Wolf –Prey Relationships ......................................11 Reproduction ........................................................3 Composition of Wolf Kills ...................................12 Mortalities .............................................................3 -

Bridge Bay & Fishing Bridge & Lake Activities for 2018

Lake Village, Fishing Bridge, and Bridge Bay Fishing Bridge General Store RV Park hard-sided Park waters are swift To Canyon Fishing vehicles only ú and cold. Swimming is Village Bridge Pelican not recommended. Creek Visitor Center To East Lake Village Lake Lodge Entrance General Store Lake Hotel All watercraft must be Bridge Bay . permitted and inspected. YELLOWSTONE LAKE Gull Point North 0 0.5 Km To West Thumb, Grant Village 0 0.5 Mi Yellowstone Lake is the largest high-eleva- − Campgrounds ) One-hour SceniCruise boat tours of tion lake (above 7,000 ft) in North America, k Fishing Bridge RV Campground is open Yellowstone Lake run several times daily, covering 286 square miles, with an average 5/11–9/5. Only hard-sided RVs are permitted. 6/11–9/9. Call 307-344-7311 for reservations. depth of 138 feet. The only outlet of the lake is No tents or soft-sided trailers. w Q at Fishing Bridge, where the Yellowstone River Other flows north. The lake is covered by ice from Bridge Bay Campground is open 5/18–9/23. = Medical Clinic 5/18–9/14, 7 AM–7 PM. mid-December to May or June. Phone: 307-242-7241 Emergency dial 911 C Food Powerful geologic processes shaped the shore- Lake Hotel Restaurant 5/11–10/8 f U.S. Post Office line of Yellowstone Lake, which overlies the Lake Hotel Deli 5/11–10/8 m Public restrooms are located at all visitor edge of the Yellowstone caldera. Glacial activity Lake Lodge Cafeteria 6/10–9/23 centers, stores, restaurants, hotels, gas stations, and volcanic events carved the central basin and at or near all picnic areas. -

COMMISSION CANDIDATES by CJ BAKER Tribune Editor Talk Budget

THURSDAY, JULY 19, 2018 108TH YEAR/ISSUE 58 COMMISSION CANDIDATES BY CJ BAKER Tribune Editor Talk budget, he Repub- lican can- development Tdidates for the Park County at public forum Commission who gathered in Powell last week seemed to gener- ally agree the county government has been run pretty well. But there were still a number of suggestions about how the county could do a bit better. Nine of the 10 Republicans seeking the three open seats on the commission attended the July 12 forum at the Park County Fairgrounds: incumbent Joe Tilden and challengers Lloyd Thiel of Clark, Pat Stuart of Heart Mountain, Dossie Overfield of Cody, Cathy Marine of Pow- ell, Anton Lehman of Heart Mountain, Richard George of Heart Mountain, Bob Berry of Cody and Zach Bowman of Cody. The only candidate missing at the Park County Republican Wom- en’s forum was Bob Stevens, a retired attorney See Commission, Page 3 Cody High School sophomore Colton Manchester (left) and teacher Dean Olenik secure a fence post above Soldier Creek in the Bighorn Mountain Range while Absentee ballots volunteers Garrett Nelson and Jasper Crofts carry dirt. Volunteers spent three days building the cow fence and will soon plant trees and bushes to provide cover and shade to help protect Yellowstone cutthroat trout in the creek. Tribune photos by Mark Davis available now Wyoming’s primary election is Aug. 21, but you don’t have to wait until then to cast your ballot. SOLDIERS FOR CUTTHROAT CONSERVATION Voters can request and cast absentee ballots VOLUNTEERS HELP PROTECT AN IMPORTANT CREEK IN THE BIGHORNS from now through Aug.