INTRODUCTION This Is a Booklet for People Interested in Cooking with Fire in Public Space. It Covers Hibachis and Portable Barbe

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Cultural Facilities 030109

A Map of Toronto’s Cultural Facilities A Cultural Facilities Analysis 03.01.10 Prepared for: Rita Davies Managing Director of Culture Division of Economic Development, Culture and Tourism Prepared by: ERA Architects Inc. Urban Intelligence Inc. Cuesta Systems Inc. Executive Summary In 1998, seven municipalities, each with its own distinct cultural history and infrastructure, came together to form the new City of Toronto. The process of taking stock of the new city’s cultural facilities was noted as a priority soon after amalgamation and entrusted to the newly formed Culture Division. City Council on January 27, 2000, adopted the recommendations of the Policy and Finance Committee whereby the Commissioner of Economic Development, Culture and Tourism was requested to proceed with a Cultural Facilities Masterplan including needs assessment and business cases for new arts facilities, including the Oakwood - Vaughan Arts Centre, in future years. This report: > considers the City of Toronto’s role in supporting cultural facilities > documents all existing cultural facilities > provides an approach for assessing Toronto’s cultural health. Support for Toronto’s Cultural Facilities Through the Culture Division, the City of Toronto provides both direct and indirect support to cultural activities. Direct support consists of : > grants to individual artists and arts organizations > ongoing operating and capital support for City-owned and operated facilities. Indirect support consists of: > property tax exemptions > below-market rents on City-owned facilities > deployment of Section 37 development agreements. A Cultural Facilities Inventory A Cultural Facility Analysis presents and interprets data about Toronto’s cultural facilities that was collected by means of a GIS (Global Information System) database. -

Dufferin Grove Park North-West Corner Improvements

Dufferin Grove Park Clubhouse and North-West Corner Park Improvements Community Resource Group Meeting – Summary November 28, 2019 Dufferin Grove Park Clubhouse and North-West Corner Park Improvements Community Resource Group Meeting – November 28, 2018 –Summary This meeting summary report was prepared by Lura Consulting, the independent facilitator and consultation specialist. If you have any questions or comments regarding the report, please contact either: Katy Aminian, City of Toronto 55 John Street, 24thFloor Toronto, Ontario M5V 3C6 416-397-4084 / [email protected] OR Liz McHardy, LURA Consulting 777 Richmond St W Toronto, Ontario M6J 0C2 416-410-3888 / [email protected] FACILITATED BY: Liz McHardy, Lura Consulting ATTENDED BY: Community Resource Group Members: Tom Berry Anne Freeman Ellen Manney Skylar Hill-Jackson Chang Liu Thomas Buckland Migs Bartula Daniel Halpert Andrea Holtslander Robin Crombie Tamara Romanchuk David Anderson Erella Ganon Katheryn Scharf Jutta Mason Shane Morgan City of Toronto: Katy Aminian, Senior Project Coordinator Peter Didiano, Supervisor Capital Projects Sofia Oliveira, Community Recreation Keith Storey, Community Recreation Supervisor Design Team (Consultants) Megan Torza, DTAH Victoria Bell, DTAH Bryce Miranda, DTAH Liz McHardy, Lura Consulting Alex Lavasidis, Lura Consulting Other: City Councilor Ana Bailão and assistant. 2 additional observers were present at the meeting ***** These minutes are not intended to provide verbatim accounts of discussions. Rather, they summarize and document the key points made during the discussions, as well as the outcomes and actions arising from the CRG meeting. Dufferin Grove Park Clubhouse and North-West Corner Park Improvements Community Resource Group Meeting – November 28, 2018 –Summary OPENING REMARKS, INTRODUCTIONS AND AGENDA REVIEW Liz McHardy, Lura Consulting, and Katy Aminian, City of Toronto, welcomed participants to the Community Resource Group (CRG) meeting. -

923466Magazine1final

www.globalvillagefestival.ca Global Village Festival 2015 Publisher: Silk Road Publishing Founder: Steve Moghadam General Manager: Elly Achack Production Manager: Bahareh Nouri Team: Mike Mahmoudian, Sheri Chahidi, Parviz Achak, Eva Okati, Alexander Fairlie Jennifer Berry, Tony Berry Phone: 416-500-0007 Email: offi[email protected] Web: www.GlobalVillageFestival.ca Front Cover Photo Credit: © Kone | Dreamstime.com - Toronto Skyline At Night Photo Contents 08 Greater Toronto Area 49 Recreation in Toronto 78 Toronto sports 11 History of Toronto 51 Transportation in Toronto 88 List of sports teams in Toronto 16 Municipal government of Toronto 56 Public transportation in Toronto 90 List of museums in Toronto 19 Geography of Toronto 58 Economy of Toronto 92 Hotels in Toronto 22 History of neighbourhoods in Toronto 61 Toronto Purchase 94 List of neighbourhoods in Toronto 26 Demographics of Toronto 62 Public services in Toronto 97 List of Toronto parks 31 Architecture of Toronto 63 Lake Ontario 99 List of shopping malls in Toronto 36 Culture in Toronto 67 York, Upper Canada 42 Tourism in Toronto 71 Sister cities of Toronto 45 Education in Toronto 73 Annual events in Toronto 48 Health in Toronto 74 Media in Toronto 3 www.globalvillagefestival.ca The Hon. Yonah Martin SENATE SÉNAT L’hon Yonah Martin CANADA August 2015 The Senate of Canada Le Sénat du Canada Ottawa, Ontario Ottawa, Ontario K1A 0A4 K1A 0A4 August 8, 2015 Greetings from the Honourable Yonah Martin Greetings from Senator Victor Oh On behalf of the Senate of Canada, sincere greetings to all of the organizers and participants of the I am pleased to extend my warmest greetings to everyone attending the 2015 North York 2015 North York Festival. -

The Campfires of Bureaucracy: in 25 Short E-Mail Chapters

THE CAMPFIRES OF BUREAUCRACY: IN 25 SHORT E-MAIL CHAPTERS Chapter 1. Dark clouds Jan.24 2007 Recreation Supervisor to Permits/Fire dept., asking for a cooking fire permit for Wallace every Sunday. Response: any campfire/ cooking fire has to be 30 meters from a building. Jan.25 Park friend Jutta Mason to Recreation Supervisor, to pass along to the Fire department: 30 meters is too far. 13 years of campfires at Dufferin, no injury. Proximity to a building gives wind protection. “We burn hardwood, no softwood and no paper, and there are seldom sparks that travel more than a few inches. The campfire site is on snow and frozen earth. We have the means right beside the fire to extinguish the fire within one minute or less.” Chapter 2. Insults and exclusion Jan.26 Meeting with Parks Supervisor and Fire Captain, who said: “the people who make these fires are imbeciles.” Recreation Supervisor, e-mail to park friend Jutta Mason: “Jutta, as per this morning’s meeting, all cooking fires in Ward 18 are to stop…I will try to set up a meeting next week with all the necessary staff in order to reach a resolution.” Jan.26 Park friend Jutta Mason to Recreation Supervisor: “I would like to emphasize that the experts in safe, successful park campfires are the people who have done them now for many years. That includes me, and also the senior park staff who have used these campfires so successfully for community-building. So, no back-room, fait-accomplit planning, please. We will need to be at the table when any new regulations are discussed. -

Fertile Ground for New Thinking Improving Toronto’S Parks

Fertile Ground for New Thinking Improving Toronto’s Parks David Harvey September 2010 Metcalf Foundation The Metcalf Foundation helps Canadians imagine and build a just, healthy, and creative society by supporting dynamic leaders who are strengthening their communities, nurturing innovative approaches to persistent problems, and encouraging dialogue and learning to inform action. Metcalf Innovation Fellowship The Metcalf Innovation Fellowship gives people of vision the opportunity to investigate ideas, models, and practices with the potential to lead to transformational change. David Harvey David Harvey has many decades of experience managing environmental and municipal issues in government and in politics. Most recently he served as Senior Advisor to the Premier of Ontario, working to develop, implement and communicate the Ontario Government’s agenda in the areas of environment, natural resources, and municipal affairs. He played a key leadership role in many aspects of the Ontario Government's progressive agenda, including the 1.8 million acre Greenbelt, the GTA Growth Plan, the City of Toronto Act and the Go Green Climate Action Plan. He was awarded a Metcalf Innovation Fellowship in 2010. Contents Executive Summary ................................................................................................. 4 Introduction – Parks and the City........................................................................... 8 “Parks” and “the City”.........................................................................................10 -

The Dufferin Grove Park As a Neighbourhood Commons

Dufferin Grove Park as a neighbourhood commons - stories from 1993 to 2015 - Jutta Mason Photo: Laura Berman Centre for Local Research into Public Space (CELOS) celos.ca Toronto 2016 Dufferin Grove Park as a neighbourhood commons Stories from 1993 to 2015 The parks, streets, community centres and other public places in Toronto are owned by the Corporation of the City of Toronto. That organization behaves quite a bit like any other corporation, with managers staking out their turf and workers defending their workplace. The people who drive on the roads or sit on the park benches or skate at the public rinks are often referred to as “cus- tomers,” “clients,” or “patrons.” There’s another way to understand a city’s public spaces: as a commons. There are various definitions of that word, for instance this one: The commons are the things that we inherit and create jointly, and that will (hopefully) last for generations to come. The commons consists of gifts of nature such as air, oceans and wildlife as well as shared social creations such as libraries, public spaces, scientific research and creative works. (www.onthecommons.org/about-commons). In 1993, Dufferin Grove Park took a turn in that direction. Here is a little collection of stories spanning the seventeen or so years when this commons was able to grow and put out its blooms. Many of the stories are told by or about the people in- volved. This is not a list, nor a ranking in order of importance, of the effort or ingenuity of the people who helped. -

West Toronto Pg

What’s Out There? Toronto - 1 - What’s Out There - Toronto The Guide The Purpose “Cultural Landscapes provide a sense of place and identity; they map our relationship with the land over time; and they are part of our national heritage and each of our lives” (TCLF). These landscapes are important to a city because they reveal the influence that humans have had on the natural environment in addition to how they continue to interact with these land- scapes. It is significant to learn about and understand the cultural landscapes of a city because they are part of the city’s history. The purpose of this What’s Out There Guide-Toronto is to identify and raise public awareness of significant landscapes within the City of Toron- to. This guide sets out the details of a variety of cultural landscapes that are located within the City and offers readers with key information pertaining to landscape types, styles, designers, and the history of landscape, including how it has changed overtime. It will also provide basic information about the different landscape, the location of the sites within the City, colourful pic- tures and maps so that readers can gain a solid understanding of the area. In addition to educating readers about the cultural landscapes that have helped shape the City of Toronto, this guide will encourage residents and visitors of the City to travel to and experience these unique locations. The What’s Out There guide for Toronto also serves as a reminder of the im- portance of the protection, enhancement and conservation of these cultural landscapes so that we can preserve the City’s rich history and diversity and enjoy these landscapes for decades to come. -

Deidre Tomlinson Designing Inclusive Urban Playscapes Across Sensorial + Socio-Spatial Boundaries By: Deidre Tomlinson

designing inclusive urban playscapes across sensorial + socio-spatial boundaries deidre tomlinson designing inclusive urban playscapes across sensorial + socio-spatial boundaries by: deidre tomlinson Submitted to OCAD University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Design in Inclusive Design Toronto, Ontario, Canada, April 2017 Deidre Tomlinson, 2017 This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-Non Commercial 4.0 International License. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/ or write to Creative Commons, 171 Second Street, Suite 300, San Francisco, California, 94105, USA. copyright notice author's declaration This document is licensed under Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial Works 4.0 License, I hereby declare that I am the sole author of this MRP. http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/ca/ This is a true copy of the MRP, including any required final revisions, as accepted by my examiners. You are free to: I authorize OCAD University to lend this MRP to other institutions or individuals for the purpose of scholarly research. Share: copy + redistribute the material in any medium or format I understand that my MRP may be made electronically available to the public. Adapt: remix, transform, and build upon the material I further authorize OCAD University to reproduce this MRP by other means, in total or in part, at the request of other institutions or individuals for the purpose of scholarly research. Under the following conditions: * Deidre Tomlinson Attribution: You must give appropriate credit, provide a link to the license, and indicate if changes were made. -

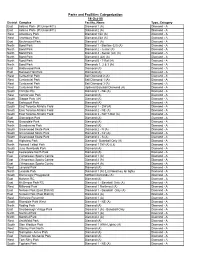

Parks and Facilities Categorization 14-Oct-05

Parks and Facilities Categorization 14-Oct-05 District Complex Facility_Name Type_Category East Adams Park- (Pt Union/401) Diamond 1 (A) Diamond - A East Adams Park- (Pt Union/401) Diamond 2 (A) Diamond - A West Amesbury Park Diamond 1/Lit (A) Diamond - A West Amesbury Park Diamond 2/Lit (A) Diamond - A East Birchmount Park Diamond 1 (A) Diamond - A North Bond Park Diamond 1 - Bantam (Lit) (A) Diamond - A North Bond Park Diamond 2 - Junior (A) Diamond - A North Bond Park Diamond 3 - Senior (Lit) (A) Diamond - A North Bond Park Diamond 4 (Lit) (A) Diamond - A North Bond Park Diamond 5 - T-Ball (A) Diamond - A North Bond Park Diamonds 1, 2 & 3 (A) Diamond - A East Bridlewood Park Diamond (A) Diamond - A East Burrows Hall Park Diamond (A) Diamond - A West Centennial Park Ball Diamond 2 (A) Diamond - A West Centennial Park Ball Diamond 1 (A) Diamond - A West Centennial Park Ball Diamond 3 (A) Diamond - A West Centennial Park Optimist Baseball Diamond (A) Diamond - A South Christie Pits Diamond 1 - NE (A) Diamond - A West Connorvale Park Diamond (A) Diamond - A South Dieppe Park AIR Diamond (A) Diamond - A West Earlscourt Park Diamond (A) Diamond - A South East Toronto Athletic Field Diamond 1 - SW (A) Diamond - A South East Toronto Athletic Field Diamond 2 - NE (A) Diamond - A South East Toronto Athletic Field Diamond 3 - NW T-Ball (A) Diamond - A East Glamorgan Park Diamond (A) Diamond - A West Gracedale Park Diamond (A) Diamond - A North Grandravine Park Diamond (A) Diamond - A South Greenwood Skate Park Diamond 2 - N (A) Diamond - A South -

Bus Lane Implementation Plan

2045.5 For Action Bus Lane Implementation Plan Date: July 14, 2020 To: TTC Board From: Chief Strategy & Customer Officer Summary The COVID-19 pandemic has shown that the TTC is a vital service in Toronto providing transportation to essential destinations including employment, healthcare, groceries and pharmacies. Although TTC ridership may be down to 22% of pre-pandemic levels, the TTC continues to serve hundreds of thousands of customer-trips on a daily basis. We also have learned through this pandemic, that bus customers have relied on our services the most - 36% of the customers that used buses prior to COVID-19 are still using the system as compared to 19% of subway customers, as of the week ending June 26. As the city and GTHA re-opens and recovery begins, it is expected that people who have the resources and option to, will return to private vehicles, taxis or private transportation companies (PTCs) more quickly than to transit in order to maintain physical distance from others. The TTC’s surface transit network plays a critical role in moving people around Toronto and we must enhance its attractiveness to ensure it continues to provide a viable alternative to the automobile. A key initiative to achieve this is the implementation of bus transit lanes, which will provide customers with a safe, reliable and fast service. The TTC’s 5-Year Service Plan & 10-Year Outlook identified a 20-point action plan including Action 4.1 Explore Bus Transit Lanes. The TTC has worked with partner divisions at the City to develop the following prioritization and implementation plan for the five corridors identified in the Plan. -

Brought to You by the Playground Writers of Canada

Brought to you by the Playground Writers of Canada Use this list to keep track of your favourite Playgrounds in Canada, or mark off the ones you have been to! Territories Carcross, YK ❏ Carcross Commons - ⭐Featured Playground http://www.earthscapeplay.com/project/carcross-yukon-playground-towers-mountain/ Whitehorse, YK ❏ The Gunnar Nilsson & Mikey Lammers Research Forest - http://www.gov.yk.ca/news/13-175.html#.WQCxK9Lyu01 Inuvik, NWT ❏ East Three School Playground - http://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/north/new-inuvik-playground-1.3787077 Hall Beach, NU ❏ Hall Beach Playground - https://www.gofundme.com/hbplayground BC Chiliwack ❏ The Landing - 9145 Corbould St, Chilliwack, BC V2P 4A6 - http://www.chilliwack.ca/main/page.cfm?id=1754&dowhat=locationView&plID=129 2 Coquitlam ❏ Como Lake Park Playground - 700 Gatensbury St, Coquitlam, BC V3J 5G8 - http://www.familyfuncanada.com/vancouver/imaginative-fun-found-como-lake-playgroun d/ ❏ Queenston Park Playground; 3415 Queenston Ave, Coquitlam, BC V3E 3H1 - ⭐Featured Playground https://www.playlsi.com/en/commercial-playground-equipment/playgrounds/queenston-p ark http://www.habitat-systems.com/project/queenston-park/ Fernie ❏ Fernie Rotary Park - 6th A Ave, Fernie, BC V0B 1M0 - http://tourismfernie.com/activities/parks-facilities/Rotary-Park Kamloops ❏ Prince Charles Park - 1198 Columbia Street, Kamloops (between 11th & 12th, Columbia & Nicola) - http://www.kamloopsplaygrounds.com/prince-charles-park/ ❏ Riverside park in Kamloops - 100 Lorne St, Kamloops, BC V2C - ⭐Featured Playground -

Volume 16 Issue 9 June 2009 Co‐Editors: Neil Mcquaid, John Domegan & Simon Proops

Volume 16 Issue 9 June 2009 Co‐editors: Neil McQuaid, John Domegan & Simon Proops In This Issue: 'Walk of Hope' My Story - Rohan Recreation Clubs Garage Sale at Milan One-Dish Meal Nutrition Claims Editorial - The Good Food Box Program Aging in Place Spring is here and we now have the opportunity to enjoy the pleasant weather. Spring is also the season when Ice Cream on the Deck many home gardeners plant their own crops of herbs and vegetables. It’s a great way to enjoy summer and eat Birthday Stars healthy, homegrown food at a low cost. But if you don’t have your own garden, finding fresh, local produce at a Pool Tournament good price is not so easy. One good thing to do is to shop at a farmer’s market in the spring and summer. Another Hot Summer Fun great idea that runs all year round is the Good Food Box program. This month, residents of our downtown buildings will learn about the pioneering efforts of two residents at our Gerrard Street building. These resident volunteers established a Good Food Box program that delivers high quality vegetables and fruits at a reasonable cost each month. And it’s delivered right to our door. The Good Food Box is operated by the FoodShare organization. FoodShare buys top quality fresh fruit and vegetables directly from farmers The Good Food Box runs like a large buying club with and from the Ontario Food centralized buying and co-ordination. Twice a month Terminal, and volunteers pack it individuals place orders for boxes with volunteer co- into green reusable boxes.