First Fossil Record of Leopard-Like Felid (Panthera Cf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Panthera Pardus) and Its Extinct Eurasian Populations Johanna L

Paijmans et al. BMC Evolutionary Biology (2018) 18:156 https://doi.org/10.1186/s12862-018-1268-0 RESEARCH ARTICLE Open Access Historical biogeography of the leopard (Panthera pardus) and its extinct Eurasian populations Johanna L. A. Paijmans1* , Axel Barlow1, Daniel W. Förster2, Kirstin Henneberger1, Matthias Meyer3, Birgit Nickel3, Doris Nagel4, Rasmus Worsøe Havmøller5, Gennady F. Baryshnikov6, Ulrich Joger7, Wilfried Rosendahl8 and Michael Hofreiter1 Abstract Background: Resolving the historical biogeography of the leopard (Panthera pardus) is a complex issue, because patterns inferred from fossils and from molecular data lack congruence. Fossil evidence supports an African origin, and suggests that leopards were already present in Eurasia during the Early Pleistocene. Analysis of DNA sequences however, suggests a more recent, Middle Pleistocene shared ancestry of Asian and African leopards. These contrasting patterns led researchers to propose a two-stage hypothesis of leopard dispersal out of Africa: an initial Early Pleistocene colonisation of Asia and a subsequent replacement by a second colonisation wave during the Middle Pleistocene. The status of Late Pleistocene European leopards within this scenario is unclear: were these populations remnants of the first dispersal, or do the last surviving European leopards share more recent ancestry with their African counterparts? Results: In this study, we generate and analyse mitogenome sequences from historical samples that span the entire modern leopard distribution, as well as from Late Pleistocene remains. We find a deep bifurcation between African and Eurasian mitochondrial lineages (~ 710 Ka), with the European ancient samples as sister to all Asian lineages (~ 483 Ka). The modern and historical mainland Asian lineages share a relatively recent common ancestor (~ 122 Ka), and we find one Javan sample nested within these. -

Large Mammal Biochronology Framework in Europe at Jaramillo: the Epivillafranchian As a Formal Biochron

Quaternary International 389 (2015) 84e89 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Quaternary International journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/quaint Large mammal biochronology framework in Europe at Jaramillo: The Epivillafranchian as a formal biochron Luca Bellucci a, Raffaele Sardella a, Lorenzo Rook b, * a Dipartimento di Scienze della Terra, “Sapienza e Universita di Roma”, P.le A. Moro 5, 00185, Roma, Italy b Dipartimento di Scienze della Terra, Universita di Firenze, via G. La Pira 4, 50121, Firenze, Italy article info abstract Article history: European large mammal assemblages in the 1.2e0.9 Ma timespan included Villafranchian taxa together Available online 3 December 2014 with newcomers, mostly from Asia, persisting in the Middle Pleistocene. A number of biochronological schemes have been suggested to define these “transitional” faunas. The term Epivillafranchian, originally Keywords: proposed by Bourdier in 1961 and reconsidered as a biochron by Kahlke in the 1990s, is at present widely Biochronology introduced in the literature. This contribution, after selecting the most representative European large Jaramillo mammal assemblages within this chronological interval, provides a new definition proposal for the Epivillafranchian Epivillafranchian as a biochron included within the Praemegaceros verticornis FO/Bison menneri FO, and Late Villafranchian Crocuta crocuta Galerian FO. Europe © 2014 Elsevier Ltd and INQUA. All rights reserved. 1. Historical background communities of this time span primarily include survivors from the latest Villafranchian, as well as more evolved taxa characteristic of The Villafranchian Mammal Age corresponds, in the Interna- the beginning Middle Pleistocene (Kahlke, 2007; Rook and tional Stratigraphic Scale, to a timespan from Late Pliocene to most Martinez Navarro, 2010). -

Phylogenetic and Phylogeographic Analysis of Iberian Lynx Populations

Journal of Heredity 2004:95(1):19–28 ª 2004 The American Genetic Association DOI: 10.1093/jhered/esh006 Phylogenetic and Phylogeographic Analysis of Iberian Lynx Populations W. E. JOHNSON,J.A.GODOY,F.PALOMARES,M.DELIBES,M.FERNANDES,E.REVILLA, AND S. J. O’BRIEN From the Laboratory of Genomic Diversity, National Cancer Institute-FCRDC, Frederick, MD 21702-1201 (Johnson and O’Brien), Department of Applied Biology, Estacio´ n Biolo´ gica de Don˜ana, CSIC, Avda. Marı´a Luisa s/n, 41013, Sevilla, Spain (Godoy, Palomares, Delibes, and Revilla), and Instituto da Conservac¸a˜o da Natureza, Rua Filipe Folque, 46, 28, 1050-114 Lisboa, Portugal (Fernandes). E. Revilla is currently at the Department of Ecological Modeling, UFZ-Center for Environmental Research, PF 2, D-04301 Leipzig, Germany. The research was supported by DGICYT and DGES (projects PB90-1018, PB94-0480, and PB97-1163), Consejerı´a de Medio Ambiente de la Junta de Andalucı´a, Instituto Nacional para la Conservacion de la Naturaleza, and US-Spain Joint Commission for Scientific and Technological Cooperation. We thank A. E. Pires, A. Piriz, S. Cevario, V. David, M. Menotti-Raymond, E. Eizirik, J. Martenson, J. H. Kim, A. Garfinkel, J. Page, C. Ferris, and E. Carney for advice and support in the laboratory and J. Calzada, J. M. Fedriani, P. Ferreras, and J. C. Rivilla for assistance in the capture of lynx. Museo Nacional de Ciencias Naturales, Don˜ana Biological Station scientific collection, Don˜ana National Park, and Instituto da Conservac¸a˜o da Natureza of Portugal provided samples of museum specimens. -

New Data on the Early Villafranchian Fauna from Vialette (Haute-Loire, France) Based on the Collection of the Crozatier Museum (Le Puy-En-Velay, Haute-Loire, France)

ARTICLE IN PRESS Quaternary International 179 (2008) 64–71 New data on the Early Villafranchian fauna from Vialette (Haute-Loire, France) based on the collection of the Crozatier Museum (Le Puy-en-Velay, Haute-Loire, France) Fre´de´ric Lacombata,Ã, Laura Abbazzib, Marco P. Ferrettib, Bienvenido Martı´nez-Navarroc, Pierre-Elie Moulle´d, Maria-Rita Palomboe, Lorenzo Rookb, Alan Turnerf, Andrea M.-F. Vallig aForschungsstation fu¨r Quata¨rpala¨ontologie Senckenberg, Weimar, Am Jakobskirchhof 4, D-99423 Weimar, Germany bDipartimento di Scienze della Terra, Universita` di Firenze, Via G. La Pira 4, 50121 Firenze, Italy cICREA, A`rea de Prehisto`ria, Universitat Rovira i Virgili-IPHES, Plac-a Imperial Tarraco 1, 43005 Tarragona, Spain dMuse´e de Pre´histoire Re´gionale de Menton, Rue Lore´dan Larchey, 06500 Menton, France eDipartimento di Scienze della Terra, Universita` degli Studi di Roma ‘‘La Sapienza’’, CNR, Ple. Aldo Moro, 500185 Roma, Italy fSchool of Biological and Earth Sciences, Liverpool John Moore University, Liverpool L3 3AF, UK g78 rue du pont Guinguet, 03000 Moulins, France Available online 7 September 2007 Abstract Vialette (3.14 Ma), like Sene` ze, Chilhac, Sainzelles, Ceyssaguet or Soleilhac, is one of the historical sites located in Haute-Loire (France). The lacustrine sediments of Vialette are the result of a dammed lake formed by a basalt flow above Oligocene layers, and show a geological setting typical for this area, where many localities are connected with maar structures that have allowed intra-crateric lacustrine deposits to accumulate. Based on previous studies and this work, a faunal list of 17 species of large mammals has been established. -

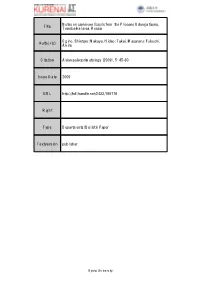

Title Notes on Carnivore Fossils from the Pliocene Udunga Fauna

Notes on carnivore fossils from the Pliocene Udunga fauna, Title Transbaikal area, Russia Ogino, Shintaro; Nakaya, Hideo; Takai, Masanaru; Fukuchi, Author(s) Akira Citation Asian paleoprimatology (2009), 5: 45-60 Issue Date 2009 URL http://hdl.handle.net/2433/199776 Right Type Departmental Bulletin Paper Textversion publisher Kyoto University Asian Paleoprimatology, vol. 5: 45-60 (2008) Kyoto University Primate Research Institute Notes on carnivore fossils from the Pliocene Udunga fauna, Transbaikal area, Russia Shintaro Ogino1*, Hideo Nakaya2, Masanaru Takai1, Akira Fukuchi2, 3 1Primate Research Institute, Kyoto University. Inuyama 484-8506, Japan 2Graduate School of Science and Engineering, Kagoshima University, Kagoshima 890-0065, Japan 3Graduate School of Natural Science and Technology, Okayama University, Okayama 700-8530, Japan *Corresponding author. e-mail: [email protected] Abstract We provide notes of carnivore fossils from the middle Pliocene Udunga fauna, Transbaikal area, Russia. The fossil carnivore assemblage consists of more than 200 specimens including eleven genera. Ursus, Parailurus, Parameles, and Ferinestrix are representative of the animals of thermophilic forest biotopes. On the other hand, Chasmaporthetes and Pliocrocuta are probably specialized in open environment. The prosperity both in foresal and semiarid carnivores indicate that the Udunga fauna is comprised of mosaic elements. Introduction The fauna dating back to the Pliocene in Udunga, Transbaikalia, Russia, comprises eleven species of mammals, such as rodents, lagomorphs, carnivores, perissodactyls, artiodactyls, and elephants (Kalmykov, 1989, 1992, 2003; Kalmykov and Maschenko, 1992, 1995 Vislobokova et al., 1993, 1995;; Erbajeva et al., 2003). The Udunga site is located on the left bank of the Temnik River, the tributary of the Selenga River in the vicinity of Udunga village (Figure 1). -

Stratified Pleistocene Vertebrates with a New Record of A

Quaternary International 382 (2015) 168e180 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Quaternary International journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/quaint Stratified Pleistocene vertebrates with a new record of a jaguar-sized pantherine (Panthera cf. gombaszogensis) from northern Saudi Arabia * Christopher M. Stimpson a, , Paul S. Breeze b, Laine Clark-Balzan a, Huw S. Groucutt a, Richard Jennings a, Ash Parton a, Eleanor Scerri a, Tom S. White a, Michael D. Petraglia a a School of Archaeology, Research Laboratory for Archaeology and the History of Art, University of Oxford, Oxford OX1 2HU, UK b Department of Geography, King's College London, Strand, London WC2R 2LS, UK article info abstract Article history: The reconstruction of Pleistocene faunas and environments of the Arabian Peninsula is critical to un- Available online 17 October 2014 derstanding faunal exchange and dispersal between Africa and Eurasia. However, the documented Quaternary vertebrate record of the Peninsula is currently sparse and poorly understood. Small collec- Keywords: tions have provided a rare insight into the Pleistocene vertebrate communities of northern Arabia, but Arabia the chronostratigraphic context of these collections is not clear. Resolving the taxonomic and chro- Pleistocene nostratigraphic affinities of this fauna is critical to emerging Quaternary frameworks. Vertebrates Here, we summarise recent investigations of the fossiliferous locality of Ti's al Ghadah in the south- Jaguar Panthera gombaszogensis western Nefud. Excavations yielded well-preserved fossil bones in a secure stratigraphic context, establishing the potential of this site to make a significant contribution to our understanding of verte- brate diversity and biogeography in the Pleistocene of Arabia. We describe the site and report our pre- liminary observations of newly-recovered stratified vertebrate remains, at present dated to the Middle Pleistocene, which include oryx (Oryx sp.), fox (Vulpes sp.), and notably stratified remains of the Ele- phantidae and a grebe (Tachybaptus sp.). -

Nyctereutes (Mammalia, Carnivora, Canidae) from Layna and the Eurasian Raccoon-Dogs: an Updated Revision

Rivista Italiana di Paleontologia e Stratigrafia (Research in Paleontology and Stratigraphy) vol. 124(3): 597-616. November 2018 NYCTEREUTES (MAMMALIA, CARNIVORA, CANIDAE) FROM LAYNA AND THE EURASIAN RACCOON-DOGS: AN UPDATED REVISION SAVERIO BARTOLINI LUCENTI1,2, LORENZO ROOK2 & JORGE MORALES3 1Dottorato di Ricerca in Scienze della Terra, Università di Pisa, Via S. Maria 53, 56126 Pisa, Italy 2Dipartimento di Scienze della Terra, Università di Firenze, Via G. La Pira 4, 50121 Firenze, Italy 3Departamento de Paleobiología. Museo Nacional de Ciencias Naturales, CSIC. C/ José Gutiérrez Abascal, 2, 28006 Madrid, Spain. To cite this article: Bartolini Lucenti S., Rook L. & Morales J. (2018) - Nyctereutes (Mammalia, Carnivora, Canidae) from Layna and the Eurasian raccoon-dogs: an updated revision Riv. It. Paleontol. Strat., 124(3): 597-616. Keywords: Taxonomy; Canidae; Europe; Pliocene; Nyctereutes. Abstract. The Early Pliocene site of Layna (MN15, ca 3.9 Ma) is renowned for its record of several mammalian taxa, among which the raccoon-dog Nyctereutes donnezani. Since the early description of this sample, new fossils of raccoon-dogs have been discovered, including a nearly complete cranium. The analysis and revision here proposed, with new diagnoses for the identified taxa, confirm the attribution of the majority of the material to the primitive taxon N. donnezani, enriching and clarifying our knowledge of the cranial and postcranial morphological variability of this species. Nevertheless, the analysis also reveals the presence in Layna of some specimens with strong morpholo- gical affinity to the derived N. megamastoides. The occurrence of such a derived taxon in a rather old site, has critical implications for the evolutionary history and dispersal pattern of these small canids. -

Iberian Lynx 1 Iberian Lynx

Iberian Lynx 1 Iberian Lynx Iberian Lynx Conservation status [1] Critically Endangered (IUCN 3.1) Scientific classification Kingdom: Animalia Phylum: Chordata Class: Mammalia Order: Carnivora Family: Felidae Genus: Lynx Species: L. pardinus Binomial name Lynx pardinus (Temminck, 1827) 1980 range map Iberian Lynx 2 2003 range map The Iberian lynx, Lynx pardinus, is a critically endangered species native to the Iberian Peninsula in Southern Europe. It is one of the most endangered cat species in the world.[2] According to the conservation group SOS Lynx, if this species died out, it would be one of the few feline extinctions since the Smilodon 10,000 years ago.[3] The species used to be classified as a subspecies of the Eurasian Lynx (Lynx lynx), but is now considered a separate species. Both species occurred together in central Europe in the Pleistocene epoch, being separated by habitat choice.[4] The Iberian lynx is believed to have evolved from Lynx issiodorensis.[5] Description In most respects, the Iberian lynx resembles other species of lynx, with a short tail, tufted ears and a ruff of fur beneath the chin. While the Eurasian Lynx bears rather pallid markings, the Iberian lynx has distinctive, leopard-like spots with a coat that is often light grey or various shades of light brownish-yellow. The coat is also noticeably shorter than in other lynxes, which are typically adapted to colder environments.[6] Some western populations were spotless, although these have recently become extinct. The head and body length is 85 to 110 centimetres (33 to 43 in), with the short tail an additional 12 to 30 centimetres (4.7 to 12 in); the shoulder height is 60 to 70 centimetres (24 to 28 in). -

Panthera (Leo/Spelaea) Vereschagini Panthera (Leo) Spelaea Rozšírený Po Celej Európe, Od Pyrenejí Až Po Ural a Kaukaz

Hic sunt leones Martin SABOL Katedra geológie a paleontológie, Prírodovedecká fakulta Univerzity Komenského v Bratislave, Slovenská republika Systém Rad: Carnivora Bowdich, 1821 Podrad: Feliformia Kretzoi, 1945 Nadčeľaď: Feloidea Fischer von Waldheim, 1817 Čeľaď: Felidae Fischer von Waldheim, 1817 Felinae Systém Rad: Carnivora Bowdich, 1821 Podrad: Feliformia Kretzoi, 1945 Nadčeľaď: Feloidea Fischer von Waldheim, 1817 Čeľaď: Felidae Fischer von Waldheim, 1817 Acinonychinae Systém Rad: Carnivora Bowdich, 1821 Podrad: Feliformia Kretzoi, 1945 Nadčeľaď: Feloidea Fischer von Waldheim, 1817 Čeľaď: Felidae Fischer von Waldheim, 1817 Machairodontinae Systém Pantherinae Panthera Oken 1816 Systém Pantherinae Panthera Oken 1816 veľké mačkovité šelmy s krátkym ňufákom, veľkým rozšírením spánkových a očnicových jám a širokými jarmovými oblúkmi História rodu Panthera 3,5 miliónov rokov pred súčastnosťou (spodný pliocén) Tanzánia – Laetoli; fosílie nesú znaky ako leva, tak aj leoparda a jaguára 2,5 miliónov rokov pred súčastnosťou (vrchný pliocén) Maroko - Ahl Al Oughlam; nálezy veľkej levotvarej mačkovitej formy opísanej ako Panthera aff. leo História rodu Panthera 2,1 miliónov rokov pred súčastnosťou (vrchný pliocén) Francúzsko - Saint-Vallier; „Panthera“ schaubi - záhadný mačkovitý druh O veľkosti leoparda, dnes klasifikovaný ako Puma pardoides 1,5 miliónov rokov pred súčastnosťou (spodný pleistocén) JAR - Transvaalske jaskyne; nález mačkovitého levotvarého mäsožravca s mozaikou bazálnych dentálnych znakov, pripomínajúc viac nálezy druhu P. gombaszoegensis -

4 Palombo 143-168NAG.Pub

Available online http://amq.aiqua.it ISSN (print): 2279-7327, ISSN (online): 2279-7335 Alpine and Mediterranean Quaternary, 29 (2), 2016, 143 - 168 Work presented during the AIQUA scientific conferences "Waiting for the Nagoya INQUA XIX Congress", held in Florence, June 18 - 19, 2015 LARGE MAMMALS FAUNAL DYNAMICS IN SOUTHWESTERN EUROPE DURING THE LATE EARLY PLEISTOCENE: IMPLICATIONS FOR THE BIOCHRONOLOGICAL ASSESSMENT AND CORRELATION OF MAMMALIAN FAUNAS Maria Rita Palombo Dipartimento di Scienze della Terra, Sapienza Università di Roma, Rome, Italy Corresponding author: M.R. Palombo <[email protected]> ABSTRACT: This research aims to investigate the large mammal faunal dynamics in SW Europe during the late Early Pleistocene. At that time, the climate forcing known as Mid-Pleistocene Revolution (MPR) induced deep, more or less gradual alterations and latitudinal dis- placements in European terrestrial biomes and exerted great influence on dispersal and dispersion of mammalian species. Large mammals did not generally move in multi-species waves of dispersal, rather each species changed its range depending on the suitability of environ- mental conditions in respect to its own environmental tolerances and ecological flexibility. Factors driving the remodelling of the range of a taxon, and time and mode of its dispersal and diffusion into SW Europe differed from species to species as from one territory to another, leading to diachronicity/asynchronicity in local first appearances/lowest local stratigraphical occurrences. As a result, correlations and bio- chronological assessments of local faunal assemblages may be difficult especially when firm chronological constraints are unavailable. Whether the peculiar composition of the late Early Pleistocene fauna, characterised by the persistence of some Villafranchian species and discrete new appearances of some taxa that will persiste during the Middle Pleistocene, may be indicative of any high rank biochronologi- cal unit is discussed. -

Pleistocene Leopards in the Iberian Peninsula: New Evidence from Palaeontological and Archaeological Contexts in the Mediterranean Region

Quaternary Science Reviews 124 (2015) 175e208 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Quaternary Science Reviews journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/quascirev Pleistocene leopards in the Iberian Peninsula: New evidence from palaeontological and archaeological contexts in the Mediterranean region * Alfred Sanchis a, , Carmen Tormo a, Víctor Sauque b, Vicent Sanchis c, Rebeca Díaz c, Agustí Ribera d, Valentín Villaverde e a Museu de Prehistoria de Valencia, Servei d'Investigacio Prehistorica, DiputaciodeVal encia, Valencia, Spain b Grupo Aragosaurus-IUCA, Departamento de Ciencias de la Tierra, Facultad de Ciencias, Universidad de Zaragoza, Zaragoza, Spain c Club d'Espeleologia l'Avern, Ontinyent, Spain d Museu Arqueologic d'Ontinyent i la Vall d'Albaida (MAOVA), Ontinyent, Spain e Departament de Prehistoria i Arqueologia, Universitat de Valencia, Valencia, Spain article info abstract Article history: This study analyses the fossil record of leopards in the Iberian Peninsula. According to the systematic and Received 7 April 2015 morphometric features of new remains, identified mainly in Late Pleistocene palaeontological and Received in revised form archaeological sites of the Mediterranean region, they can be attributed to Panthera pardus Linnaeus 7 July 2015 1758. The findings include the most complete leopard skeleton from the Iberian Peninsula and one of the Accepted 11 July 2015 most complete in Europe, found in a chasm (Avenc de Joan Guiton) south of Valencia. The new citations Available online xxx and published data are used to establish the leopard's distribution in the Iberian Peninsula, showing its maximum development during the Late Pleistocene. Some references suggest that the species survived Keywords: Panthera pardus for longer here (Lateglacial-Early Holocene) than in other parts of Europe. -

Locomotor Adaptations in Plio-Pleistocene Large Carnivores from the Italian Peninsula: Palaeoecological Implications

Current Zoology 57 (3): 269−283, 2011 Locomotor adaptations in Plio-Pleistocene large carnivores from the Italian Peninsula: Palaeoecological implications Carlo MELORO* Hull York Medical School, The University of Hull, Loxley Building, Cottingham Road Hull HU6 7RX, UK Abstract Mammalian carnivores are rarely considered for environmental reconstructions because they are extremely adaptable and their geographic range is usually large. However, the functional morphology of carnivore long bones can be indicative of lo- comotor behaviour as well as adaptation to specific kind of habitats. Here, different long bone ratios belonging to a subsample of extant large carnivores are used to infer palaeoecology of a comparative sample of Plio-Pleistocene fossils belonging to Italian paleo-communities. A multivariate long bone shape space reveals similarities between extant and fossil carnivores and multiple logistic regression models suggest that specific indices (the brachial and the Mt/F) can be applied to predict adaptations to grass- land and tropical biomes. These functional indices exhibit also a phylogenetic signal to different degree. The brachial index is a significant predictor of adaptations to tropical biomes when phylogeny is taken into account, while Mt/F is not correlated any- more to habitat adaptations. However, the proportion of grassland-adapted carnivores in Italian paleo-communities exhibits a negative relationship with mean oxygen isotopic values, which are indicative of past climatic oscillations. As climate became more unstable during the Ice Ages, large carnivore guilds from the Italian peninsula were invaded by tropical/closed-adapted spe- cies. These species take advantage of the temperate forest cover that was more spread after 1.0 Ma than in the initial phase of the Quaternary (2.0 Ma) when the climate was more arid [Current Zoology 57 (3): 269–283, 2011].