A ROAD of HER OWN a S' a Written Creative Work

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Hampi, Badami & Around

SCRIPT YOUR ADVENTURE in KARNATAKA WILDLIFE • WATERSPORTS • TREKS • ACTIVITIES This guide is researched and written by Supriya Sehgal 2 PLAN YOUR TRIP CONTENTS 3 Contents PLAN YOUR TRIP .................................................................. 4 Adventures in Karnataka ...........................................................6 Need to Know ........................................................................... 10 10 Top Experiences ...................................................................14 7 Days of Action .......................................................................20 BEST TRIPS ......................................................................... 22 Bengaluru, Ramanagara & Nandi Hills ...................................24 Detour: Bheemeshwari & Galibore Nature Camps ...............44 Chikkamagaluru .......................................................................46 Detour: River Tern Lodge .........................................................53 Kodagu (Coorg) .......................................................................54 Hampi, Badami & Around........................................................68 Coastal Karnataka .................................................................. 78 Detour: Agumbe .......................................................................86 Dandeli & Jog Falls ...................................................................90 Detour: Castle Rock .................................................................94 Bandipur & Nagarhole ...........................................................100 -

Pencintaalam Newsletter of the Malaysian Nature Society

PENCINTAALAM NEWSLETTER OF THE MALAYSIAN NATURE SOCIETY www.mns.my www.mns.my September 2019 The Night Life in FRIM By NEC FRIM, Kepong “Switch off your torchlights and look up, everyone,” said Wan Mohd. Nafizul Hal-Alim Wan Ahmad, a Forest Research Institute Malaysia (FRIM) nature guide, to all the participants in his group. Looking upwards, the view of FRIM’s jewel, the ‘crown of shyness’ of the Meranti Belang (Shorea resinosa) trees, took their breath away. The view was magnificent and it felt like we had been transported to another dimension. “The phenomenon of the jigsaw puzzle pattern occurred because the seedlings of Shorea resinosa were planted in the same year. The even aged stands developed this unique formation, a natural phenomenon which is rarely found elsewhere. Most Crown of shyness in FRIM during night-time of the trees are approximately 83 years old, 35-50m in height and 40-60cm in diameter. The average On 3rd May 2019, the Night Life in FRIM programme by FRIM and Malaysian Nature canopy openings are between 10-15cm.” said Wan. Society (MNS) was organised as part of the training under the MOU between FRIM and Shorea resinosa is critically endangered due to loss MNS. It was led by Dr. Noor Azlin Yahya, the Head of Ecotourism and Urban Forestry of habitat and the conservation status is vulnerable Programme (EUF) of FRIM. for Malaysia. The aim of this programme was to recognise the wonderful biodiversity in FRIM, such as nocturnal animals, to increase the awareness of Malaysians on the importance of conserving the country’s natural heritage. -

Charlestonexplore Our Guide to the Most Charming Sights in This Historic City CONTENTS

Fall/Winter 2020 CharlestonExplore Our guide to the most charming sights in this historic city CONTENTS WELCOME MESSAGE CHECKING IN THE VIEW FROM HERE Stan Soroka’s latest Club A villa, a theme park and an Experience Victorian Member update oceanfront resort await glamour in Scotland MEET THE TEAM CHARLESTON Sylvia C. gives us her best tips on Rich in culture, history and enjoying Las Vegas like a local architecture, Charleston delivers Southern charm ONE CITY, FIVE WAYS: LOS CABOS From beaches to bars, discover Los Cabos, Mexico SESOKO THE CLUBHOUSE THE Q&A Escape to this island and our upcoming HGV property in Japan Discover the great cities of America and How Maui’s tranquil environment Europe with ClubPartner Perk Great inspired Interior Designer Beatrice Adventures Girelli’s work for HGV 48 HOURS IN CARLSBAD CLUB PARTNER PERKS RCI How to spend the best Sail from Athens to Rome National Park ideas for 48-hours at Marbrisa on the Azamara Pursuit your next road trip Welcome from Stan Soroka Dear Club Members, As we head into 2021, I find myself optimistic about the future of travel. While the COVID-19 situation continues to evolve, there’s a sense of re-awakening that has me encouraged. Las Vegas shows are live once more. Hawaii is finally welcoming trans-Pacific travelers, and our re-opened properties on The Big Island and Oahu cannot wait to see you back. As demand for rooms continues to increase each month, I strongly urge you to book as early as possible to find the dates you wish to travel. -

Ultimate Patagonia Detailed Itinerary

ULTIMATE PATAGONIA OCTOBER 31 – NOVEMBER 11, 2021 DETAILED ITINERARY Embark on a captivating 12-day journey through the vast, pristine wilderness of Patagonia. After touring the vibrant metropolis of Santiago, head south to Chile’s Patagonian Lake District, a region of snow-capped volcanoes, crystal clear lakes and mystic forests. Your first stop will be Pucón and the lovely Vira Vira lodge. Choose from tailor-made adventures such as trekking in a national park, horseback riding with a Chilean huaso (cowboy), white-water rafting on the Trancura River, kayaking on Lake Tinquilco, or mountain biking to the foot of the Villarrica Volcano. Travel onward to the Hotel AWA, perched along the sparkling shoreline of Lake Llanquihue, just outside of Puerto Varas. Enjoy a private excursion to Petrohué Falls and explore Vicente Pérez Rosales National Park. Finally, head to Puerto Natales, gateway to Patagonia’s crown jewel, Torres del Paine National Park, set amid monolithic granite spires, azure colored lakes, and glaciers. The Singular Patagonia lodge offers a comfortable base from which to choose from a number of excursions both in and surrounding the park including a boat trip to massive glaciers, spectacular kayaking, horseback riding, bird-watching, and biking. GROUP SIZE: 14-20 guests PRICING: $9,995 per person double occupancy / $13,635 single occupancy STUDY LEADER: To be announced SCHEDULE BY DAY WEDNESDAY, NOVEMBER 3 PUCON B=Breakfast, L=Lunch, R=Reception, D=Dinner Today, explore the lakes, rivers, fjords, and peaks of Chile’s Lake District. Vira Vira’s personal excursion managers and your tour SUNDAY, OCTOBER 31 director will help you choose from tailor-made DEPART U.S. -

Summer Packages 2009

GB The Peak of Tirol. SUMMER PACKAGES 2009 oetztal.com All Highlights at a Glance A Heartfelt Welcome! SUMMER IN GENERAL May June July August September October Ötztal. Tirol‘s highlight. We promise the most beautiful Ötztal All Inclusive and exciting days of the year as our valley is rich in attractions. You can choose from an array of truly MADE TO MEASURE ADVENTURES unbeatable offers and made to measure deals. Enjoy Rafting, Canyoning and Biking flipping through our „Summer Packages 2009“ folder Women‘s Camp with Karen Eller which comprises an infinite variety of activities and Basic Single Trail Camp with Holger Meyer exciting adventures available throughout the valley. Expert Single Trail Camp with Holger Meyer The Ötztal has it all: the finding place of Ötzi the Ice- Total Rock man, the healing powers for body and mind at the Längenfeld Spa Center, endless walking paths, scenic Barbara Bacher & David Lama Camp mountain bike trails and the really outstanding Ötztal Tirol‘s Highest Mountain Card giving access to countless highlights across the Welcome to the World of 3,000 m Peaks valley. Everyone will find a perfect deal for wonderful, tailor-made holidays. Anticipation is half the fun! WALKING TOWARDS INNER WELL-BEING Exciting Nature Don‘t hesitate to contact us for special requests or Close to the Sky if you have further questions. We are always at your The Journey is the Reward disposal. Bike & Yoga with Karen Eller Alpenpuls® – Hiking with Peter Schlickenrieder Wishing you all the best! V2B – Vitality2Business Optimize your Metabolic -

![G]Kfnlkg, G]Kfnl Dg Bf}/F–;'?Jfn / 9Fsf 6F]Kldf 7Ffl6g] O'jfsf] ;+Vof Lbgfg'lbg A9\B} 5](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/7419/g-kfnlkg-g-kfnl-dg-bf-f-jfn-9fsf-6f-kldf-7ffl6g-ojfsf-vof-lbgfglbg-a9-b-5-4257419.webp)

G]Kfnlkg, G]Kfnl Dg Bf}/F–;'?Jfn / 9Fsf 6F]Kldf 7Ffl6g] O'jfsf] ;+Vof Lbgfg'lbg A9\B} 5

;fdflhs YEARS A H ;~hfndf TRUsteD FLYING D D /dfpg]x? U B Issue # 36 May 2019 www.buddhaair.com TIGERLAND VISIT BARDIA, WHERE CULTURE & WILDLIFE UNITE Patan beyond klxnf] p8fg Mangalbazar TAMANG g]kfnLkg, HERITAGE g]kfnL dg TRAIL facebook.com/ buddhaair @airbuddha @buddhaairnepal www.buddhaair.com Mobile App Download the power to fly ! FeaTUreS Search & Pay Directly On The App Login To Your Royal Club Create Your Own Profile Login As Guest Offline Ticket at your fingertips Check Ticket and Flight Status Get Detailed Flight Information Get Inspiration For Your Next Travel Destination DOwNlOaD FOr Free 37 Namaste and welcome on board Buddha Air! I would like to wish our flyers a Happy Nepali New Year 2076 BS! In 2075, we celebrated many wonderful milestones like the addition of two more ATR 72-500 aircrafts to our fleet family (9N-AMU and AN-AMY), the launch of our revamped website and mobile app and also the start of night flights to Bhadrapur. As there is an increase in demand for convenient air travel, we hope that these facilities will help to make your journey favourable and comfortable. We have some wonderful news to share visiting the lesser known areas of Mangalbazar in Patan with you for this Nepali New Year. From 27 May 2019, we (Attractions of Patan Beyond Mangalbazar) and visiting are operating nonstop and direct flights between Kolkata the beautiful garden paradise of Godavari. If you are and Kathmandu. Along with flight connections to these looking for an escape from the capital, “A Weekend Away cultural cities, our travel subsidiary, Buddha Holidays has From Kathmandu” is sure to invigorate your wanderlust. -

Catalonia Is Nature Proposals This Catalogue Contains Proposals for Tourism in Contact with Nature

Catalonia is nature Proposals This catalogue contains proposals for tourism in contact with nature. The prices quoted in the catalogue are per person with VAT included. The Catalan Tourist Board accepts no responsibility for variations in the published prices. © Generalitat de Catalunya © Catalan Tourist Board Catalonia France Paisatges Barcelona Mediterranean Sea Catalonia 2 Catalonia is nature Contents Catalonia is nature 5 Enjoying nature 6 Hiking 6 Cycle tourism 7 Water, land and airborne activities 8 Catalonia is adventure 8 Great views with your feet on the ground 8 Catalonia in a single flight 9 Nature activities 9 Catalonia is nature Proposals 11 Tot Catalunya 13 Barcelona 29 Paisatges Barcelona 33 Costa Barcelona 43 Costa Brava 53 Costa Daurada 71 Terres de l’Ebre 81 Terres de Lleida 87 Pirineus 95 Val d’Aran 129 Associated entities 132 List of entities 134 3 4 Paisatges Barcelona. Ruta del Ter Catalonia is nature Thanks to its contrasting landscapes and benign climate, Catalonia is the ideal destination for lovers of all kinds of active tourism pursuits. The Pyrenees provide the perfect settings for hiking and cycle tourism, skiing, adventure sports and family outings. And only a few kilometres away from our most celebrated peaks, the long beaches in the south or the hidden coves in the north, with their crystalline waters, are ideal for water-sport enthusiasts. 5 Costa Brava. Hiking on the Ruta del Ter Enjoying nature range from west to east, from the Cantabrian to the Mediter- Nature makes Catalonia an attractive ranean at Cap de Creus. The Carros de Foc is a hiking trail that destination for all those who wish to make takes between five and seven days which connects the Pallars, first-hand acquaintance, from all viewpoints the Alta Ribagorça and the Val d’Aran. -

KERALA in Indiaandyoucanimagine Howharditwillbetoleave Before Youeven Gethere

© Lonely Planet Publications 960 KERALA KERALA Kerala Kerala is where India slips down into second gear, stops to smell the roses and always talks to strangers. A strip of land between the Arabian Sea and the Western Ghats, its perfect climate flirts unabashedly with the fertile soil, and everything glows. An easy-going and successful so- cialist state, Kerala has a liberal hospitality that stands out as its most laudable achievement. The backwaters that meander through Kerala are the emerald jewel in South India’s crown. Here, spindly networks of rivers, canals and lagoons nourish a seemingly infinite number of rice paddies and coconut groves, while sleek houseboats cruise the water highways from one bucolic village to another. Along the coast, slices of perfect, sandy beach beckon the sun-worshipping crowd, and far inland the mountainous Ghats are covered in vast planta- tions of spices and tea. Exotic wildlife also thrives in the hills, for those who need more than just the smell of cardamom growing to get their juices flowing. This flourishing land isn’t good at keeping its secret: adventurers and traders have been in on it for years. The serene Fort Cochin pays homage to its colonial past, each building whispering a tale of Chinese visitors, Portuguese traders, Jewish settlers, Syrian Christians and Muslim mer- chants. Yet even with its colonial distractions, Kerala manages to cling to its vibrant traditions: Kathakali – a blend of religious play and dance; kalarippayat – a gravity-defying martial art; and theyyam – a trance-induced ritual. Mixed with some of the most tastebud-tingling cuisine in India and you can imagine how hard it will be to leave before you even get here. -

Winterguide16-17.Pdf

PARK DISTRICT2016-17Winter Program Guide Dress-up play at The Exploritorium Table of Contents Special Events ..........................................................44–49 Birthday Parties .............................................................. 43 Information District Policies & Info .................................................. 80 Map, Rentals & Facilities ......................................81–83 Sponsorships ................................................................... 48 Registration Info, Jobs & Staff Contacts................. 85 CALENDAR Commemorative Bricks ............................................... 84 August Feature Stories December 9 Deadline for Santa’s Hotline & Letters from Santa—p. 44 Weber Leisure Center renovation ............................ 15 15 Skokie Resident Fall Registration Begins The Exploritorium - Discovery & Freedom ........... 36 22 Non-Resident 15 Winter Fall RegistrationResident Registration Begins Emily Oaks, Skokie’s Outdoor Jewel .................50–51 26–28 Skokie’s 17 Backlot Breakfast Bash with p. 44 Santa—p. 44 Programs Athletic Leagues .....................................................22–23 27 Skokie’s Backlot Dash 5K p. 44 Babysitting at Weber .................................................... 12 22 Winter Non-resident Registration Baseball ...................................................................... 23, 30 Basketball ...........................................................22–23, 29 September 29 Itty Bitty New Year—p. 44 Batting Cages .......................................................... -

Planet of Escapes There Are Hundreds of Other Great Trips, Apps, and Lodges out There, but the 50 Winners of Our 2014 Travel Awards Have Them

Planet of Escapes There are hundreds of other great trips, apps, and lodges out there, but the 50 winners of our 2014 Travel Awards have them snorkeling all beat. in belize Now geT goiNg. by Tim Neville ANd sTephANie peArsoN 52 OUTSIDE MAGAZINE OUTSIDEONLINE.COM 53 87°55’51.74”W 51°0’0”S 73°0’0”W 54.0000° N 125.0000° W 18°02’27”S 141°24’34”W 18°0’50.21”N 87°55’51.74”W 51°0’0”S 73°0’0”W 54.0000° N 125.0000° W 18°02’27”S 141°24’34”W 51°0’0”S 73°0’0”W 54.0000° N 125.0000° W 18°02’27”S 141°24’34”W 18°0’50.21”N 87°55’51.74”W 87°55’51.74”W 51°0’0”S 73°0’0”W 54.0000° N 2014 outside travel awards 125.0000° W 18°02’27”S 141°24’34”W 18°0’50.21”N 87°55’51.74”W 51°0’0”S 73°0’0”W Tour of Flanders orval Abbey, belgium patagonia dispatches Awasi by horse dispatches destinations Best New Lodge vanilla oil. From $2,100 for south destinations three nights, all-inclusive;columns Lab rat water awasipatagonia.com Caye Winner columns Lab rat FOB Awasi Runner-Up PatagoniaFOB Lodge, Chile Mallard Moun- 1 It’s not hard to find a 1tain Lodge, great lodge near Torres British Columbia del Paine National Park The sweetest lodges are Tuamotu Islands with a and its larger-than-life remote yet right on top 180-square-mile lagoon scenery. -

Goose Creek District Newsletter

Goose Creek District Newsletter November 2020 Volume 12, Issue 4 from The Scoutmaster Minute blog, Special Interest: http://thescoutmasterminute.net/2015/08/26/knowledge-to-action/ District Knowledge to Action • Goose Creek Day Camp 2021 – pg 2 There are those times as a Scoutmaster that leave you inspired. The other night I had one of those moments as I began to share my Scoutmaster minute with the Troop. Like Advancement most Troops, we have young men that make up the membership of the unit. Ranging • BSA Distinguished from 10 1/2 to 17 these young men tend to be exactly what we want them to be… boys. Conservation Service Award – pg 7 We all know that at times boys do not always think before they act and they certainly • Camp Snyder Merit Badge allow emotion to overrule logic. And so it is when working with boys. As much as I hate Week – pg 8 the saying “boys will be boys”... boys will be boys. There is nothing at all wrong with that, as long as Adults are Adults and work to being good teachers, coaches and Council/National mentors to the boys. • Eagle Scouts & College – pgs 11-12 So the Scoutmaster minute this week was addressing some issues that came up, New High Adventure Base Portal nothing earth shattering, but boys heading down a trail that would not lead them to – pg 11 positive outcomes. Heading them off now will save lots of grief later. It comes down to, like most things in Scouting and life, living the Oath and Law. -

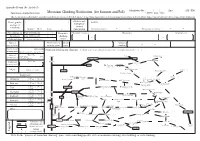

Mountain Climbing Notification (For Summer and Fall) Submission Date

Appended Form (Re: Article 5) Submission date: / / Time: (AM / PM) Governor of Gifu Prefecture Mountain Climbing Notication (for Summer and Fall) ( yyyy / mm / dd ) is notication is submitted in accordance with the provisions of Article 5, Section 1 regarding the prevention of mountaineering accidents in the Northern Alps Zone and Active Volcano Zone of Gifu Prefecture. ()Address and Name, gender, Address: emergency and age of contact submitter Gender: M / F ( Age: ) information Normal telephone: - - Emergency telephone: - - Start climbing on: Date (yyyy/mm/dd): / / Mountain- Mountain entrance Waypoints Mountain exit Return on: Date (yyyy/mm/dd): / / climbing ~ ~ Additional days: days (returning on ) route Mountaineering group Purpose of Group Contact - - mountain climbing membership overview name number Provisions and days’ worth Mountain climbing trip (diagram) Indicate your route with arrows and enter overnight stays in the ( / ). drinking water Carried provisions (Yes, days’ worth / No) Yes / No Means of ( / ) (Wireless: Hz) Toyama Toyama Takamagahara communication (Mobile phone: ) ( / ) Hietsu Tunnel Oritate( / ) Yakushizawa Cabin( / ) Yes / No Kamioka Mountaineering Tarodaira Cabin insurance (provider) ( / ) Utsubo Kitanomata ▲ Shelter Cabin Mt. Kitanomatadake ( / ) Lodging ▲Mt. Kurobegorodake Renge( / ) Cabin / Tent Tengaizan( / ) Kumonodaira Lodge( / ) Kurobegoro Lodge( / ) Equipment Mt. Kasagatake Kasagatake Eboshi( / ) ▲ ( / ) ( / ) Lodge · Crampons ( Yes / No) Mt. Shakujodake▲ Mt. Mitsumatarengedake Mitsumata Lodge ( / ) ▲Mt.