1 Theory of Literature U

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Metaphor-II Metaphor-II Contents: 10.1 Dead Metaphors 10.2 Conceptual

Metaphor-II Linguistic Stylistics Metaphor-II Figures of Speech Paper Coordinator Prof. Ravinder Gargesh Module ID & Name Lings_P-LS10 Metaphor-II Content Writer Dr. V.P. Sharma Email id [email protected] Phone 9312254857 Contents: 10.1 Dead Metaphors 10.2 Conceptual Metaphor Theory 10.3 Extended Metaphor 10.4 Mixed Metaphor 10.5 Metaphor in Literary and Non-literary discourse 10.1 Dead Metaphors We have noted that a metaphor is characterized by linguistic deviation. This characteristic allows metaphor, particularly poetic metaphors, to create novel and original combinations of ideas, objects and sensations. But as they come into common use, the novelty wears off and there is no perception of semantic deviation. More significantly, they lose their iconicity: in ‘root cause of the problem’ or ‘heated argument’, the original metaphor has lost its figurative ‘charge’; ‘root cause of a problem’ is simply the ‘fundamental reason for the occurrence of the problem’, and ‘heated argument ‘ is another expression for ‘angry exchange of words’. Such metaphors are dead metaphors. But metaphors never really die. The metaphors that ‘die’ in poetic language come to ‘live’ in ordinary language. The habit of words to extend their meaning by metaphor and then cease to be metaphorical is a fact of language. It further allows metaphors to be used to fill gaps in vocabulary: leg of a table, wings of a building, clock hands, World Wide Web, crashing or hanging (as in computer hangs), surf, crash course. In such cases of metaphorical extensions, there are no literal substitutes for these expressions. This is true of all languages. -

Creating Literary Analysis

Creating Literary Analysis v. 1.0 This is the book Creating Literary Analysis (v. 1.0). This book is licensed under a Creative Commons by-nc-sa 3.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/ 3.0/) license. See the license for more details, but that basically means you can share this book as long as you credit the author (but see below), don't make money from it, and do make it available to everyone else under the same terms. This book was accessible as of December 29, 2012, and it was downloaded then by Andy Schmitz (http://lardbucket.org) in an effort to preserve the availability of this book. Normally, the author and publisher would be credited here. However, the publisher has asked for the customary Creative Commons attribution to the original publisher, authors, title, and book URI to be removed. Additionally, per the publisher's request, their name has been removed in some passages. More information is available on this project's attribution page (http://2012books.lardbucket.org/attribution.html?utm_source=header). For more information on the source of this book, or why it is available for free, please see the project's home page (http://2012books.lardbucket.org/). You can browse or download additional books there. ii Table of Contents About the Authors................................................................................................................. 1 Acknowledgments................................................................................................................. 2 Dedications............................................................................................................................ -

CHAPTER 2 LITERATURE REVIEW 2.1 Theoretical Framework in This

ADLN Perpustakaan Universitas Airlangga CHAPTER 2 LITERATURE REVIEW 2.1 Theoretical Framework In this chapter, the writer will explain about the theory which is applied to analyze Rabbit Hole play as the chosen literary work in this study. Regarding the statement of the problem, the theory which is used in this study is New Criticism; which means the approach based only on the text itself. Besides explaining about New Criticism as the main theory and several formal elements such as characterization, plot, symbol, and also the theme which is the main idea of the story, this chapter also contains related studies with the similar issue that can support this study. There will be three related studies for this study that will be discussed in the end of this chapter. First, the writer will explain about the main theory; that is New Criticism. New Criticism is an approach which focuses on the text itself to find the meaning of a literary work. New Criticism refuses to pay attention to the external factors such as author’s background, reader’s response, and another factor which is not merely about the text of literary work. According to Tyson, the external factors such as author’s background cannot always be a guide to provide information to analyze a literary work (Tyson 136), because New Criticism focuses only on the text, Skripsi BECCA’S SURVIVAL ATTEMPT AFTER THE DEATH OF HER BELOVEDLUTFITA MAUDY PRASTIKASARI SON IN DAVID LINDSAY-ABAIRE’S RABBIT HOLE: A NEW CRITICISM STUDY ADLN Perpustakaan Universitas Airlangga the validity of the text meaning is reasonable. -

In Literary Theory: a Comparative Critical Study Mahmoud Mohamed Ali Ahmad Elkordy University of South Carolina

University of South Carolina Scholar Commons Theses and Dissertations 2016 The evelopmeD nt of ‘Meaning’ in Literary Theory: A Comparative Critical Study Mahmoud Mohamed Ali Ahmad Elkordy University of South Carolina Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarcommons.sc.edu/etd Part of the Comparative Literature Commons Recommended Citation Elkordy, M. M.(2016). The Development of ‘Meaning’ in Literary Theory: A Comparative Critical Study. (Doctoral dissertation). Retrieved from https://scholarcommons.sc.edu/etd/3794 This Open Access Dissertation is brought to you by Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. بسم هللا الرحمن الرحيم وبه نستعين وصلى هللا وسلم وبارك على محمد النبي اﻷمي وعلى آله وصحبه وأحبابه أجمعين يارب ارض عنا آمين الحمد هلل في اﻷولى واﻵخرة وسﻻم على عباده الذين اصطفى هللا خير The Development of ‘Meaning’ in Literary Theory: A Comparative Critical Study by Mahmoud Mohamed Ali Ahmad Elkordy Bachelor of Arabic Language Al-Azhar University, 2010 Master of Arts University of London, 2011 ــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــ Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Comparative Literature College of Arts and Sciences University of South Carolina 2016 Accepted by: Paul Allen Miller, Major Professor Maḥmūd Lāshīn, Committee Member Jeanne Garane, Committee Member Alexander Beecroft, Committee Member Lacy Ford, Senior Vice Provost and Dean of Graduate Studies بسم هللا الرحمن الرحيم وبه نستعين وصلى هللا وسلم وبارك على محمد النبي اﻷمي وعلى آله وصحبه وأحبابه أجمعين يارب ارض عنا آمين الحمد هلل في اﻷولى واﻵخرة وسﻻم على عباده الذين اصطفى هللا خير Abstract This research project studies different approaches to the question of meaning in literary texts in medieval Islamic critical traditions and modern Western literary criticism. -

Aristotle's Poetics

Aristotle's Poetics José Angel García Landa Universidad de Zaragoza http://www.garcialanda.net 1. Introduction 2. The origins of literature 3. The nature of poetry 4. Theory of genres 5. Tragedy 6. Other genres 7. The Aristotelian heritage José Angel García Landa, "Aristotle's Poetics" 2 1. Introduction Aristotle (384-322 BC) was a disciple of Plato and the teacher of Alexander the Great. Plato's view of literature is heavily conditioned by the atmosphere of political concern which pervaded Athens at the time. Aristotle belongs to a later age, in which the role of Athens as a secondary minor power seems definitely settled. His view of literature does not answer to any immediate political theory, and consequently his critical approach is more intrinsic. Aristotle's work on the theory of literature is the treatise Peri poietikés, usually called the Poetics (ca. 330 BC). Only part of it has survived, and that in the form of notes for a course, and not as a developed theoretical treatise. Aristotle's theory of literature may be considered to be the answer to Plato's. Of course, he does much more than merely answer. He develops a whole theory of his own which is opposed to Plato's much as their whole philosophical systems are opposed to each other. For Aristotle as for Plato, the theory of literature is only a part of a general theory of reality. This means that an adequate reading of the Poetics 1 must take into account the context of Aristotelian theory which is defined above all by the Metaphysics, the Ethics, the Politics and the Rhetoric. -

Literary Theory, an Introduction Second Edition

Literary Theory Second Edition For Charles Swann and Raymond Williams Literary Theory An Introduction SECOND EDITION Terry Eagleton St Catherine '5 College Oxford Blackwell Publishing © 1983,1996 by Terry Eagleton BLACKWELL PUBLISHING 350 Main Street, Malden, MA 02148-5020,USA 9600 Garsington Road, Oxford OX4 2DQ, UK 550 Swanston Street, Carlton, Victoria 3053, Australia The right of Terry Eagleton to be identified as the Author of this Work has been asserted in accordance with the UK Copyright, Designs, and Patents Act 1988. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, . photocopying, recording or otherwise, except as permitted by the UK Copyright, Designs, and Patents Act 1988, without the prior permission of the publisher. First published 1983 Second edition 1996 10 2005 Library ofCongress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Eagleton, Terry, 1943- Literary Theory: an introduction / Terry Eagleton - 2nd ed. p. em. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 0-631-20188-2 (pbk: alk. paper) 1. Criticism-History-20th Century. 2. Literature-History and criticism- Theory, etc. 1.Title PN94.E2 1996 96-4572 801'.95'0904-dc20 CIP ISBN-13:978-0-631-20188-5(pbk: alk. paper) A catalogue record for this title is available from the British Library. Set in 10.5 on 12.5 pt Ehrhardt by Best-set Typesetter Ltd, Hong Kong Printed and bound in India by Replika Press Pvt Ltd, Kundli The publisher's policy is to use permanent paper from mills that operate a sustainable forestry policy, and which has been manufactured from pulp processed using acid-free and elementary chlorine-free practices. -

The Advantages of Critical and Systematic Literary Taxonomies: a Review Article of New Work by Cerquiglini, Juvan, and Zima

CLCWeb: Comparative Literature and Culture ISSN 1481-4374 Purdue University Press ©Purdue University Volume 2 (2000) Issue 4 Article 14 The Advantages of Critical and Systematic Literary Taxonomies: A Review Article of New Work by Cerquiglini, Juvan, and Zima Kristof Jacek Kozak University of Alberta Follow this and additional works at: https://docs.lib.purdue.edu/clcweb Part of the Comparative Literature Commons, and the Critical and Cultural Studies Commons Dedicated to the dissemination of scholarly and professional information, Purdue University Press selects, develops, and distributes quality resources in several key subject areas for which its parent university is famous, including business, technology, health, veterinary medicine, and other selected disciplines in the humanities and sciences. CLCWeb: Comparative Literature and Culture, the peer-reviewed, full-text, and open-access learned journal in the humanities and social sciences, publishes new scholarship following tenets of the discipline of comparative literature and the field of cultural studies designated as "comparative cultural studies." Publications in the journal are indexed in the Annual Bibliography of English Language and Literature (Chadwyck-Healey), the Arts and Humanities Citation Index (Thomson Reuters ISI), the Humanities Index (Wilson), Humanities International Complete (EBSCO), the International Bibliography of the Modern Language Association of America, and Scopus (Elsevier). The journal is affiliated with the Purdue University Press monograph series of Books in Comparative Cultural Studies. Contact: <[email protected]> Recommended Citation Kozak, Kristof Jacek. "The Advantages of Critical and Systematic Literary Taxonomies: A Review Article of New Work by Cerquiglini, Juvan, and Zima." CLCWeb: Comparative Literature and Culture 2.4 (2000): <https://doi.org/10.7771/ 1481-4374.1097> This text has been double-blind peer reviewed by 2+1 experts in the field. -

Download Download

Vol. 11, 2020 A new decade for social changes ISSN 2668-7798 www.techniumscience.com 9 772668 779000 Technium Social Sciences Journal Vol. 11, 84-95, September 2020 ISSN: 2668-7798 www.techniumscience.com The Prague School Theory of Drama & Theatre and SFL Patrice Quammie-Wallen The Hong Kong Polytechnic University [email protected] Abstract. The Prague Linguistic Circle’s theories of drama and theatre were ground-breaking in the early 20th century. While the many and varied writings of its scholars are only recently gaining global recognition the application of the many semiotic principles as it applies to the stage remain to be fully utilised. Literary analyses over the modern decades have comparatively ignored the play text for stylistic treatment, due significantly to the fact that a suitable framework that can manage the ‘combinatory quality of theatre’ remains at large. Systemic functional linguistics (SFL), a developed, language-based semiotic framework whose foundations share Prague School principles of structure and function, has been suggested to be capable of managing that combinatory quality. This paper, agreeing with that position, compares Prague School principles with that of SFL to advance the further position that combined use of SFL and Prague theatre theories can potentially construct that elusive primary dynamic connecting the page and the stage, as well as facilitate mutual development of both frameworks. Keywords. Prague School Drama and Theatre Theory, systemic functional linguistics, play text, semiotics, functional analysis 1. Introduction The original Prague school began as a collection of linguists and literature, music and theatre theoreticians in 1926 under Vilém Mathésius with Roman Jakobson serving as vice-president up till his exodus to America in 1941. -

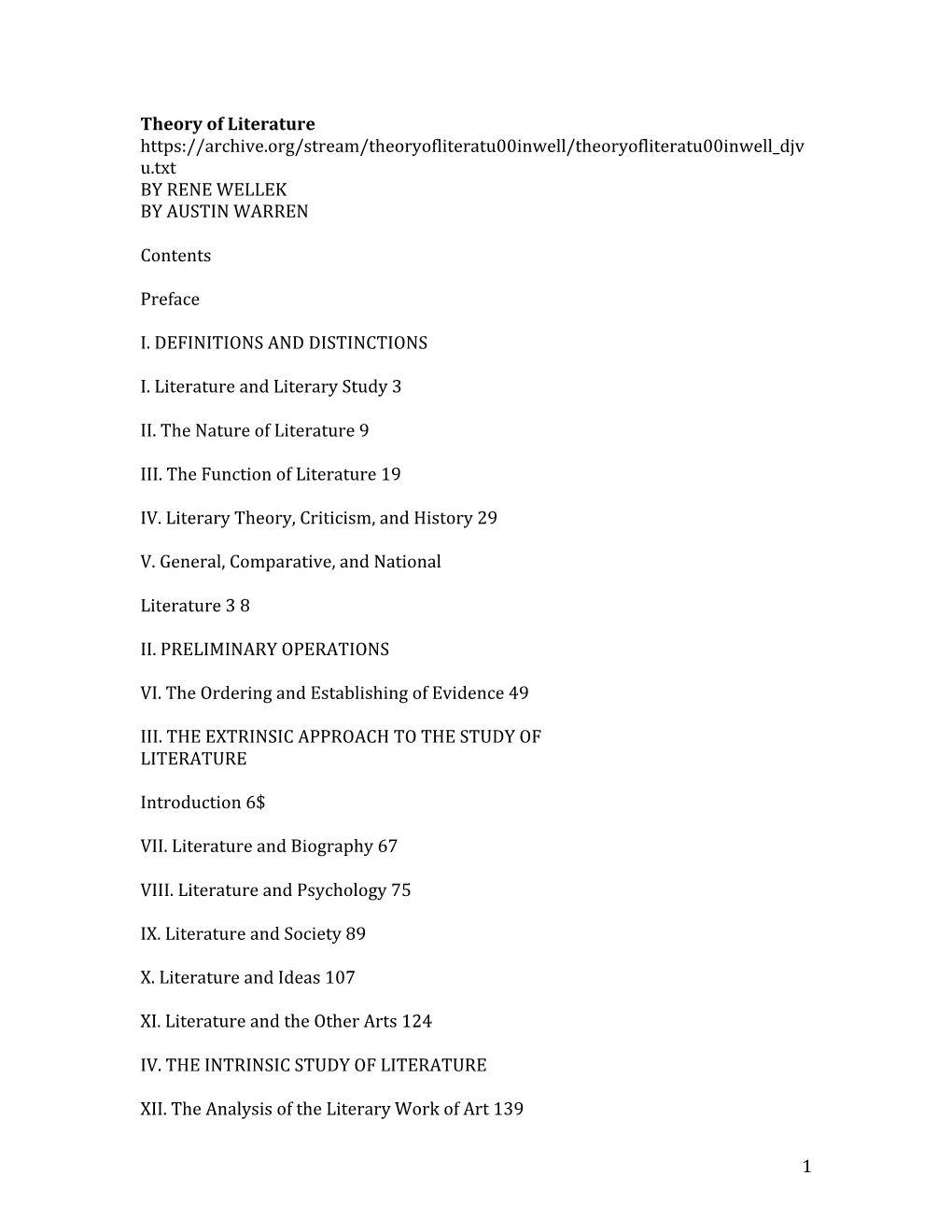

136 Theory of Literature Rene Wellek and Austin Warren

Theory of Literature Rene Wellek and Austin Warren (Harcourt, Brace and Company, 1948) Ritika Batabyal1 The 1944-46 collaboration between Rene Wellek and Austin Warren led to the publication of one of the most influential and comprehensive analysis in the field of literary theory, methodology and criticism. Their urge to provide an “organon” of method resulted in the coming of shape of Theory of Literature. Harcourt, Brace and Company first published the book in December 1948. In the Preface to the third edition of the book, it has been remarked that the book has been translated into Spanish, Italian, Japanese, Korean, German, Portuguese, Hebrew and Gujarati. This explicitly evinces the impact of the book in 20th century literary scenario. Theory of literature is considered to be the first work to systematize literary theory. Though Wellek and Warren came from different backgrounds and training they believed that literary scholarship and criticism are compatible and literary study over all other things needs to be specifically literary. The book is divided into four sections encompassing a wide range of subjects. The first part deals with definitions and distinctions. Here Wellek and Warren delve with the nature and function of literature, and there is a constant endeavour to distinguish between literature and literary study. In this section the book also deals with literary theory, history and criticism and it tries to show that these are inter dependent and cannot be put into watertight compartments. The final chapter in this section tries to give a definition of General Literature, Comparative Literature and National Literature and in the process it lays down the major characteristics of General, Comparative, and National Literature. -

A Study on Characterization of the Main Character in “The Fault in Our Stars”

Research in English and Education (READ), 1(1), 26-33, August 2016 E-ISSN 2528-746X A Study on Characterization of the Main Character in “The Fault in Our Stars” Annisa Patmarinanta*1,2, Potjut Ernawati1 1Syiah Kuala University, Banda Aceh 2CV. Andil Muda Mandiri, Banda Aceh *Corresponding author: [email protected] Abstract This research analyzes The Fault in Our Stars, a novel by Green (2012). The Fault in Our Stars is one of Green’s novels that reflect the reality of life. This research focuses on the personalities of Hazel and August, the main characters of the novel. The author took from (Djasi, 2000) as the framework of the main character characterization. The design of this study was a descriptive qualitative study. The aim of this study is to see Hazel’s and August’s personalities as the main character of The Fault in Our Stars. By examining the character dialog and quotes of the novel, and related issues on the topic are taken from printed and online including journal, books, and magazine. In order to achieve the goal of this study the researcher applied theory of character and characterization. Some characteristics that represent Hazel’s and August’s character traits are: depressed, books lover, fighter, stubborn, chivalrous, kind, and loyal. Besides characterization of the main characters this thesis also represents the theme of this novel that is fighting for life. Keywords: Characterization, character, the fault in our stars, novel. 1. INTRODUCTION There are several ways in expressing ideas especially in a literary work. There is a literary work that brings us to the world of dreams and takes us away from reality. -

CLAUDIA BRODSKY ______471 Broadway, #2 New York, New York 10013 Tel: 917.822.3579

CLAUDIA BRODSKY _________________________________ 471 Broadway, #2 New York, New York 10013 tel: 917.822.3579 EDUCATION AND DEGREES 1984 Yale University, Comparative Literature, Ph.D. 1982 Ludwig-Maximilians Universität, München, W. Germany 1981 Yale University, M.Phil. 1977 Albert-Ludwigs Universität, Freiburg, W. Germany 1976 Harvard University, B.A., magna cum laude, in English and Comparative Literature 1976 Sorbonne Collège d'Eté, Paris, France AWARDS AND HONORS 2009 Invited Senior Fellow, Freiburg Institute for Advanced Studies, Albert-Ludwigs Universität, Freiburg, Germany 2000-01 Alexander von Humboldt Fellow (Renewed Appointment) 1996-97 Alexander von Humboldt Fellow 1995 Elected Directeur de Programme, Collège International de Philosophie, Paris 1988-91 Elias Boudinot Bicentennial Prize Fellowship, Princeton University 1987-88 Howard Fellowship, Howard Foundation for the Humanities, Providence, R.I. 1984 Ph.D. dissertation awarded Distinction, Yale University 1982-83 Whiting Fellowship, Whiting Foundation, Yale University 1982 DAAD Fellowship for Advanced Doctoral Candidates, München, W. Germany 1981 Ph.D. Examination awarded Distinction, Yale University 1980-84 Danforth Fellowship, Danforth Foundation, Yale University 1979-82 Robert E. Darling Fellowship for Excellence in the Humanities, Yale University Graduate School 1979 Mary Cady Tew Prize for Best First Year Graduate Student in the Humanities and Social Sciences, Yale University 1978-79 Yale University Fellowship, Yale University Graduate School 1976-77 W. German Government Fellowship, Freiburg, W. Germany 1976 Award of summa cum laude, Honors Essay, Harvard University 1975-76 Josephine de Karman National Fellowship for Outstanding Achievement in the Humanities, Harvard University, De Karman Foundation TEACHING AND RELATED PROFESSIONAL EXPERIENCE 2009 Invited Lecturer, Freiburg Institute for Advanced Studies, Universität-Freiburg, 2 Germany. -

Poetic Thoughts and Poetic Effects: a Relevance Theory Account of the Literary Use of Rhetorical Tropes and Schemes

POETIC THOUGHTS AND POETIC EFFECTS: A RELEVANCE THEORY ACCOUNT OF THE LITERARY USE OF RHETORICAL TROPES AND SCHEMES. Adrian Pilkington Thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirement for the degree of PhD University College London May 1994 ( LONDOIJ ABSTRACT This thesis proposes an account of the effects achieved by the poetic use of rhetorical tropes and schemes in the light of recent developments in pragmatic theory. More specifically it discusses and attempts to develop the relevance theory account of poetic effects. Much recent debate in literary studies has centred on the question as to whether literary communication is best explained in terms of text-internal linguistic properties or socio-cultural phenomena. This thesis considers such views in the light of the theories of language and communication they assume. It then proposes an alternative theoretical account of literary communication grounded in cognitive pragmatic theory. It argues that the relevance theory account of poetic effects may make a significant contribution to such an account. A brief outline of relevance theory is followed by a more detailed analysis of metaphor and a brief consideration of epizeuxis and various verse effects, insofar as they contribute to poetic style. it is natural for pragmatic theory to concentrate on the communication of assumptions, propositional forms with a logical structure over which inferences can be performed. Although the account of poetic effects and poetic thoughts developed here will be partially characterised in such terms, an attempt will also be made to account for the communication of affective and other non-propositional effects. Any theory of stylistic effects in general, and poetic style in particular, must, it will be argued, include such an account.