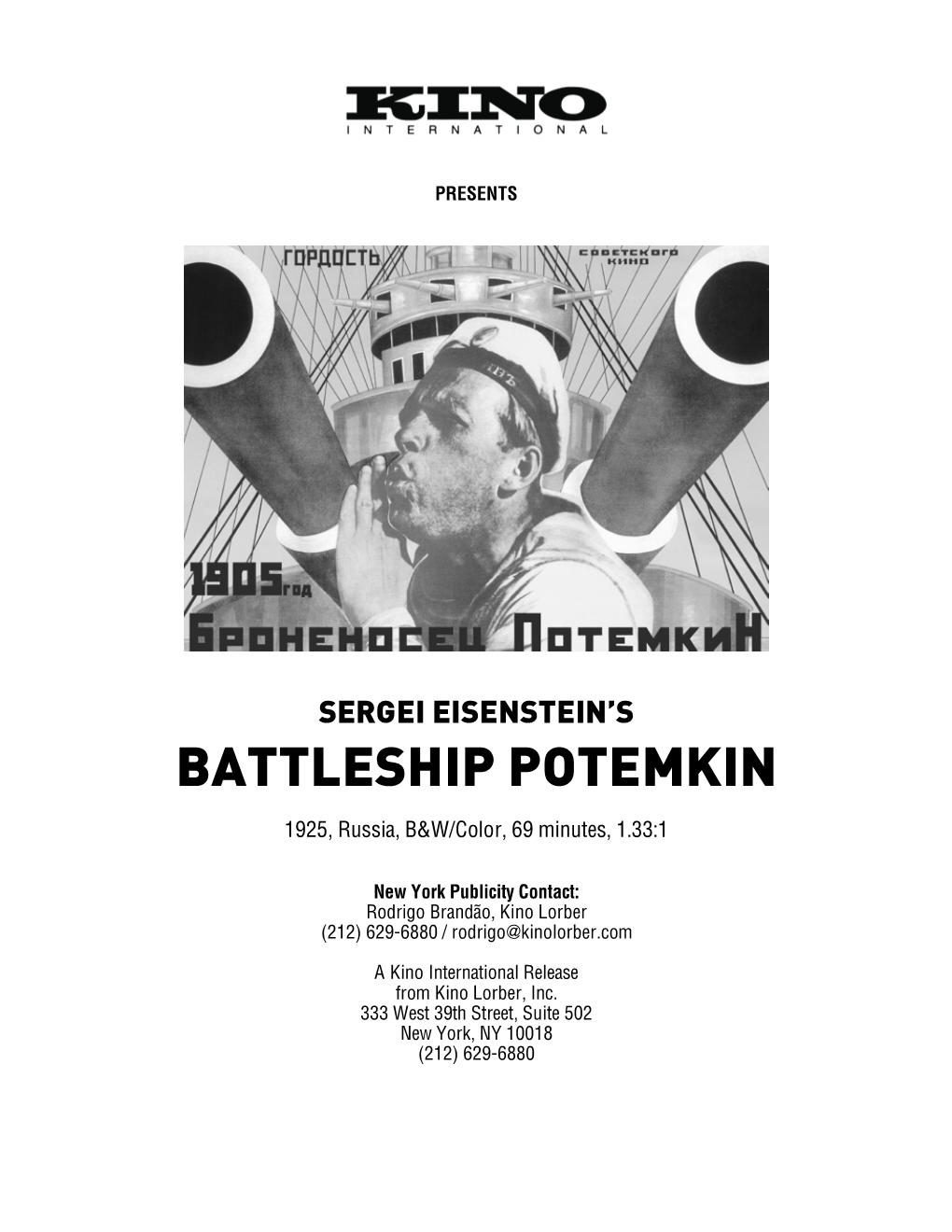

Battleship Potemkin

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Dear Friends, Contents

Dear Friends, This is a vibrant moment in Latvian film. from the 1960s to the present day, and who By Dita Rietuma, Riga, Latvia, was chosen as the host location is a past recipient of an EFA award. director of the of the 2014 European Film Academy awards Animation is also an essential part of National Film ceremony. 2014 was also marked as a time Latvian cinema – both puppet and illustrated Centre of Latvia when a new generation of directors came animation have been evolving in Latvia since into Latvian cinema. Many – journalists, the 1970s. 2014 saw two cardinally-different critics – are likening them to the French features: The Golden Horse, based on a New Wave of the 1960s, with their realistic, national classic, and Rocks in M y Pockets – an impulsive aesthetic and take on original, feministic and very personal view the zeitgeist of the time. Mother, I Love from director Signe Baumane, it is also You (2013) by Jānis Nords and Modris (2014) by Latvia’s contender for the Oscars. Juris Kursietis, have received awards and Latvia is open to collaboration, offering a recognition at the Berlinale and San multitude of diverse locations and several Sebastian festivals respectively. tax-rebate schemes, but most A strong documentary film tradition importantly – a positive and vital cinematic continues on in Latvia, and is embodied by environment. living legend, documentary filmmaker Ivars Discover Latvia, its films, filmmakers and Seleckis, whose career has spanned a period creative opportunities! 6 Contents Doing It Right. Overview 2 A Poetic Touch. Director Ivars Seleckis 8 From Behind the Listening Post. -

History Is Made in the Dark 4: Alexander Nevsky: the Prince, the Filmmaker and the Dictator

1 History Is Made in the Dark 4: Alexander Nevsky: The Prince, the Filmmaker and the Dictator In May 1937, Sergei Eisenstein was offered the opportunity to make a feature film on one of two figures from Russian history, the folk hero Ivan Susanin (d. 1613) or the mediaeval ruler Alexander Nevsky (1220-1263). He opted for Nevsky. Permission for Eisenstein to proceed with the new project ultimately came from within the Kremlin, with the support of Joseph Stalin himself. The Soviet dictator was something of a cinephile, and he often intervened in Soviet film affairs. This high-level authorisation meant that the USSR’s most renowned filmmaker would have the opportunity to complete his first feature in some eight years, if he could get it through Stalinist Russia’s censorship apparatus. For his part, Eisenstein was prepared to retreat into history for his newest film topic. Movies on contemporary affairs often fell victim to Soviet censors, as Eisenstein had learned all too well a few months earlier when his collectivisation film, Bezhin Meadow (1937), was banned. But because relatively little was known about Nevsky’s life, Eisenstein told a colleague: “Nobody can 1 2 find fault with me. Whatever I do, the historians and the so-called ‘consultants’ [i.e. censors] won’t be able to argue with me”.i What was known about Alexander Nevsky was a mixture of history and legend, but the historical memory that was most relevant to the modern situation was Alexander’s legacy as a diplomat and military leader, defending a key western sector of mediaeval Russia from foreign foes. -

Exploration of Narrative Devices in Documentary Propaganda Across Different

Exploration of Narrative Devices in Documentary Propaganda Across Different Media Platforms Comparative Analysis of the USSR in the 1920s and Russia in the 2010s Kirill Chernyshov A Research Paper Submitted to the University of Dublin, in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science Interactive Digital Media 2018 Declaration I have read and I understand the plagiarism provisions in the General Regulations of the University Calendar for the current year, found at: http://tcd.ie/calendar I have also completed the Online Tutorial on avoiding plagiarism ‘Ready, Steady, Write’, located at http://tcd-ie.libguides.com/plagiarism/ready-steady-write I declare that the work described in this Research Paper is, except where other stat- ed, entirely my own work and has not been submitted as an exercise for a degree at this or any other University. Signed: Kirill Chernyshov Date: Permission to Lend and/or Copy I agree that Trinity College Library may lend or copy this research paper upon request. Signed: Kirill Chernyshov Date: Acknowledgements To my family and friends in different parts of the world for their support while being so far away. To my new friends here, flatmates, and classmates, for being there and making this experience so exciting. To Vivienne, my supervisor, for the fantastic lectures, positive spirit, and valuable guidance throughout the year. Summary In this research paper, two periods in Russian and Soviet history are compared in or- der to identify the differences in narrative devices used in the 1920s and 2010s. These two cases were chosen to analyse due to, apart from the fact that today’s Russia is a comparatively young direct successor of the USSR, that predictably causes some similarities in the people’s identity and values, there are some similarities in historical and political context of these two periods that were revealed in this paper. -

Staging the Urban Soundscape in Fiction Film

Echoes of the city : staging the urban soundscape in fiction film Citation for published version (APA): Aalbers, J. F. W. (2013). Echoes of the city : staging the urban soundscape in fiction film. Maastricht University. https://doi.org/10.26481/dis.20131213ja Document status and date: Published: 01/01/2013 DOI: 10.26481/dis.20131213ja Document Version: Publisher's PDF, also known as Version of record Please check the document version of this publication: • A submitted manuscript is the version of the article upon submission and before peer-review. There can be important differences between the submitted version and the official published version of record. People interested in the research are advised to contact the author for the final version of the publication, or visit the DOI to the publisher's website. • The final author version and the galley proof are versions of the publication after peer review. • The final published version features the final layout of the paper including the volume, issue and page numbers. Link to publication General rights Copyright and moral rights for the publications made accessible in the public portal are retained by the authors and/or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. • Users may download and print one copy of any publication from the public portal for the purpose of private study or research. • You may not further distribute the material or use it for any profit-making activity or commercial gain • You may freely distribute the URL identifying the publication in the public portal. -

The Film Music of Edmund Meisel (1894–1930)

The Film Music of Edmund Meisel (1894–1930) FIONA FORD, MA Thesis submitted to The University of Nottingham for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy DECEMBER 2011 Abstract This thesis discusses the film scores of Edmund Meisel (1894–1930), composed in Berlin and London during the period 1926–1930. In the main, these scores were written for feature-length films, some for live performance with silent films and some recorded for post-synchronized sound films. The genesis and contemporaneous reception of each score is discussed within a broadly chronological framework. Meisel‘s scores are evaluated largely outside their normal left-wing proletarian and avant-garde backgrounds, drawing comparisons instead with narrative scoring techniques found in mainstream commercial practices in Hollywood during the early sound era. The narrative scoring techniques in Meisel‘s scores are demonstrated through analyses of his extant scores and soundtracks, in conjunction with a review of surviving documentation and modern reconstructions where available. ii Acknowledgements I would like to thank the Arts and Humanities Research Council (AHRC) for funding my research, including a trip to the Deutsches Filminstitut, Frankfurt. The Department of Music at The University of Nottingham also generously agreed to fund a further trip to the Deutsche Kinemathek, Berlin, and purchased several books for the Denis Arnold Music Library on my behalf. The goodwill of librarians and archivists has been crucial to this project and I would like to thank the staff at the following institutions: The University of Nottingham (Hallward and Denis Arnold libraries); the Deutsches Filminstitut, Frankfurt; the Deutsche Kinemathek, Berlin; the BFI Library and Special Collections; and the Music Librarian of the Het Brabants Orkest, Eindhoven. -

NASSAU-THESIS-2013.Pdf

Copyright by David Eduardo Nassau 2013 The Thesis Committee for David Eduardo Nassau Certifies that this is the approved version of the following thesis : Sergey Eisenstein: the use of graphic violence in Strike and Potemkin APPROVED BY SUPERVISING COMMITTEE: Supervisor: Joan Neuberger Keith Livers Sergey Eisenstein: the use of graphic violence in Strike and Potemkin by David Eduardo Nassau, B.A International Relations Thesis Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of The University of Texas at Austin in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts The University of Texas at Austin December 2013 Dedication I dedicate this thesis to my father, the late Pedro Nassau (b. 22 July 1952-d. 28 May 2012), who always insisted that if I put my mind into something, I can accomplish anything. Nothing is beyond the realm of possibility. Eternal memory to him. Abstract Sergey Eisenstein: the use of graphic violence in Strike and Potemkin David Eduardo Nassau , M.A The University of Texas at Austin, 2013 Supervisors: Joan Neuberger Being a very prominent film director with several recognisable works, Sergey Eisenstein has been studied extensively from all angles. The aim of this dissertation is to analyse his first two movies, Strike and Battleship Potemkin, both of them stand out when seen in the context of 1920s cinema. Both films are known for introducing strong, graphic violence in cinema and at the same time the films shed light on sensitive social issues such as income disparity, government indifference as well -

Reading Eisenstein's Capital

Sergei Eisenstein. Diary entry, February 23, 1928. Rossiiskii Gosudarstevennyi Arkhiv Literatury i Iskusstva ( Russian State Archive for Literature and Art). 94 https://doi.org/10.1162/grey_a_00251 Downloaded from http://www.mitpressjournals.org/doi/pdf/10.1162/grey_a_00251 by guest on 01 October 2021 Dance of Values: Reading Eisenstein’s Capital ELENA VOGMAN “The crisis of the democracy shoUld be Understood as crisis of the conditions of exposition of the political man.” 1 This is how Walter Benjamin, in 1935, describes the decisive political conseqUences of the new medial regime in the “age of technological reprodUcibility.” Henceforth, the political qUestion of representation woUld be determined by aesthetic conditions of presentation. 2 In other words, what is at stake is the visibility of the political man, insofar as Benjamin argUes that “radio and film are changing not only the fUnction of the professional actor bUt, eqUally, the fUnction of those who, like the politician, present themselves before these media.” 3 Benjamin’s text evokes a distorting mirror in which the political man appears all the smaller, the larger his image is projected. As a resUlt, the contemporary capitalist conditions of reprodUction bring forth “a new form of selection”—an apparatUs before which “the champion, the star, and the dictator emerge as victors.” 4 The same condition of technological reprodUction that enables artistic and cUltUral transmission is inseparably tied to the conditions of capi - talist prodUction, on the one hand, and the rise of fascist regimes, on the other. Benjamin was not the first to draw an impetUs for critical analysis from this relationship. -

The Stage of the Mountains

Leopold- Franzens Universität Innsbruck The Stage of the Mountains A TRANSNATIONAL AND HISTORICAL SURVEY OF THE MOUNTAINS AS A STAGE IN 100 YEARS OF MOUNTAIN CINEMA Diplomarbeit Zur Erlangung des akademischen Grades eines Mag. phil. an der Philologisch- Kulturwissenschaftlichen Fakultät der Leopold-Franzens-Universität Innsbruck Eingereicht bei PD Mag. Dr. Christian Quendler von Maximilian Büttner Innsbruck, im Oktober 2019 Eidesstattliche Erklärung Ich erkläre hiermit an Eides statt durch meine eigenhändige Unterschrift, dass ich die vorliegende Arbeit selbständig verfasst und keine anderen als die angegebenen Quellen und Hilfsmittel verwendet habe. Alle Stellen, die wörtlich oder inhaltlich den angegebenen Quellen entnommen wurden, sind als solche kenntlich gemacht. Die vorliegende Arbeit wurde bisher in gleicher oder ähnlicher Form noch nicht als Magister- /Master-/Diplomarbeit/Dissertation eingereicht. ______________________ ____________________________ Datum Unterschrift Table of Contents Acknowledgments .................................................................................................................... 4 Introduction .............................................................................................................................. 1 Mountain Cinema Overview ................................................................................................... 4 The Legacy: Documentaries, Bergfilm and Alpinism ........................................................... 4 Bergfilm, National Socialism and Hollywood -

The Function of Music in Sound Film

THE FUNCTION OF MUSIC IN SOUND FILM By MARIAN HANNAH WINTER o MANY the most interesting domain of functional music is the sound film, yet the literature on it includes only one major work—Kurt London's "Film Music" (1936), a general history that contains much useful information, but unfortunately omits vital material on French and German avant-garde film music as well as on film music of the Russians and Americans. Carlos Chavez provides a stimulating forecast of sound-film possibilities in "Toward a New Music" (1937). Two short chapters by V. I. Pudovkin in his "Film Technique" (1933) are brilliant theoretical treatises by one of the foremost figures in cinema. There is an ex- tensive periodical literature, ranging from considered expositions of the composer's function in film production to brief cultist mani- festos. Early movies were essentially action in a simplified, super- heroic style. For these films an emotional index of familiar music was compiled by the lone pianist who was musical director and performer. As motion-picture output expanded, demands on the pianist became more complex; a logical development was the com- pilation of musical themes for love, grief, hate, pursuit, and other cinematic fundamentals, in a volume from which the pianist might assemble any accompaniment, supplying a few modulations for transition from one theme to another. Most notable of the collec- tions was the Kinotek of Giuseppe Becce: A standard work of the kind in the United States was Erno Rapee's "Motion Picture Moods". During the early years of motion pictures in America few original film scores were composed: D. -

Avant Garde Vs. Moderism

Barrett 1 Mike Barrett 21G.031 Professor Scribner 20 March 2003 Conflict and Resolution of Modernism and the Historical Avant-garde The historical avant-garde and the modernist movement have fundamental differences in both their conceptions of art and its role in the greater scheme of society. While the avant-garde uses drastic new ideas to express and reinforce dramatic political and social changes, modernism attempts to celebrate modern society without connecting artwork back to life. Where the avant-garde and modernism meet, they exist in a symbiotic relationship, with the avant-garde pulling modernism to new thresholds of social progress. The dialectic of the two creates conflict which moves society in a progressive direction, but the resolution keeps humanity connected with the constant social progress of modernity. Modernism’s rise in the twentieth century brought about a preoccupation with form and formalism in society. Modern society evolves through market expansion and appropriation of new technologies, and modern art glorifies this trend without putting it in a social or political context. The focus on mechanization and technology creates a situation where humanity is left only the option of plugging in, or being hopelessly lost in the maelstrom of modernity (Berman 26, 27). High modernism promoted “rigid polarities and flat totalizations” as seen in artwork of that period (Berman 23, 24). Modernist painting stressed the difference between art and life, focusing on the awareness of paint on the canvas rather than an accurate or evocative view on the natural 1 Barrett 2 world. Trends in modernism are towards mechanization and the “machine aesthetic,” and away from concerns of social life (Berman 26). -

Visual Metaphors for the People a Study of Cinematic Propoganda in Sergei Eisenstein’S Film

VIsual Metaphors for the people A Study of Cinematic Propoganda in Sergei Eisenstein’s Film ashley brown This paper attempTs To undersTand how The celebraTed and conTroversial figure of sergei eisensTein undersTood and conTribuTed To The formaTion of The sovieT union Through his films of The 1920s. The lens of visual meTaphors offer a specific insighT inTo how arTisTic choices of The direcTor were informed by his own pedagogy for The russian revoluTion. The paper asks The quesTions: did eisensTein’s films reflecT The official parTy rheToric? how did They inform or moTivaTe The public Toward The communisT ideology of The early sovieT union? The primary sources used in This pa- per are from The films Strike (1925), BattleShip potemkin (1926), octoBer (1928), and the General line (1929). eisensTein creaTed visual meTaphors Through The juxTaposi- Tion of images in his films which alluded To higher concepTs. a shoT of a worker followed by The shoT of gears Turning creaTed The concepT of indusTry in The minds of The audience. Through visual meTaphors, iT is possible To undersTand The moTives of eisensTein and The communisT parTy. iT is also possible, wiTh The aid of secondary sources, To see how Those moTives differed. “Language is much closer to film than painting is. For example, aimed at the “... organization of the psychology of the in painting the form arises from abstract elements of line and masses.”6 Works about Eisenstein in the field of film color, while in cinema the material concreteness of the image theory examine Eisenstein’s career in theater, the evolution within the frame presents—as an element—the greatest of his approach to montage, and his artistic expression.7 difficulty in manipulation. -

Films from Latvia 2016/2019

FILMS FROM LATVIA 2017 / 2019 CONTENT 2 FICTIONS 13 FICTIONS COMING SOON FILMS 35 SHORT FICTIONS 50 DOCUMENTARIES 75 DOCUMENTARIES COMING SOON 112 ANIMATION FROM 123 ANIMATION COMING SOON INDEXES 136 English Titles 138 Original Titles LATVIA 140 Directors 142 Production Companies 144 ADDRESSES OF PRODUCTION 2017 / COMPANIES USEFUL ADDRESSES 149 Main Distributors in Latvia 149 Main Film Institutions 150 International Film Festivals and 2019 Events in Latvia FICTIONS THE CHRONICLES OF MELANIE MELĀNIJAS HRONIKA Director Viestur Kairish 120’, Latvia National Premiere 01.11.2016, Riga, Splendid Palace International Premiere 21.11.2016, Tallin Black Nights FF (Estonia) Scriptwriter Viestur Kairish Cinematographer Gints Bērziņš Production Designer Ieva Jurjāne Costume Designers Ieva Jurjāne, Gita Kalvāne Makeup Designer Mari Vaalasranta Original Music Arturs Maskats, Aleksandrs Vaicahovskis, Kārlis Auzāns Sound Directors Aleksandrs Vaicahovskis, Robert Slezák Editor Jussi Rautaniemi The 14th of June 1941, Soviet-occupied Latvia: Without warning, the authorities break into Main Cast Sabine Timoteo, Edvīns Mekšs, the house of Melanie and her husband Aleksandrs and force them to leave everything Ivars Krasts, Guna Zariņa, Maija Doveika, behind. Together with more than 15 000 Latvians, Melanie and her son get deported to Viktor Nemets Siberia. In her fight against cold, famine and cruelty, she only gains new strength through Producers Inese Boka-Grūbe, Gints Grūbe the letters she writes to Aleksandrs, full of hope for a free Latvia and a better tomorrow.