Exeter Register 2000

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Notes on the Parish of Mylor, Cornwall

C.i i ^v /- NOTES ON THE PARISH OF MYLOR /v\. (crt MVI.OK CII r RCII. -SO UIH I'OKCil AND CROSS O !• ST. MlLoKIS. [NOTES ON THE PARISH OF MYLOR CORNWALL. BY HUGH P. OLIVEY M.R.C.S. Uaunton BARNICOTT &- PEARCE, ATHEN^UM PRESS 1907 BARNICOTT AND PEARCE PRINTERS Preface. T is usual to write something as a preface, and this generally appears to be to make some excuse for having written at all. In a pre- face to Tom Toole and his Friends — a very interesting book published a few years ago, by Mrs. Henry Sandford, in which the poets Coleridge and Wordsworth, together with the Wedgwoods and many other eminent men of that day figure,—the author says, on one occasion, when surrounded by old letters, note books, etc., an old and faithful servant remon- " " strated with her thus : And what for ? she " demanded very emphatically. There's many a hundred dozen books already as nobody ever reads." Her hook certainly justified her efforts, and needed no excuse. But what shall I say of this } What for do 1 launch this little book, which only refers to the parish ot Mylor ^ vi Preface. The great majority of us are convinced that the county of our birth is the best part of Eng- land, and if we are folk country-born, that our parish is the most favoured spot in it. With something of this idea prompting me, I have en- deavoured to look up all available information and documents, and elaborate such by personal recollections and by reference to authorities. -

Gothic Riffs Anon., the Secret Tribunal

Gothic Riffs Anon., The Secret Tribunal. courtesy of the sadleir-Black collection, University of Virginia Library Gothic Riffs Secularizing the Uncanny in the European Imaginary, 1780–1820 ) Diane Long hoeveler The OhiO STaTe UniverSiT y Press Columbus Copyright © 2010 by The Ohio State University. all rights reserved. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data hoeveler, Diane Long. Gothic riffs : secularizing the uncanny in the european imaginary, 1780–1820 / Diane Long hoeveler. p. cm. includes bibliographical references and index. iSBn-13: 978-0-8142-1131-1 (cloth : alk. paper) iSBn-10: 0-8142-1131-3 (cloth : alk. paper) iSBn-13: 978-0-8142-9230-3 (cd-rom) 1. Gothic revival (Literature)—influence. 2. Gothic revival (Literature)—history and criticism. 3. Gothic fiction (Literary genre)—history and criticism. i. Title. Pn3435.h59 2010 809'.9164—dc22 2009050593 This book is available in the following editions: Cloth (iSBn 978-0-8142-1131-1) CD-rOM (iSBn 978-0-8142-9230-3) Cover design by Jennifer Shoffey Forsythe. Type set in adobe Minion Pro. Printed by Thomson-Shore, inc. The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of the american national Standard for information Sciences—Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials. ANSi Z39.48-1992. 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 This book is for David: January 29, 2010 Riff: A simple musical phrase repeated over and over, often with a strong or syncopated rhythm, and frequently used as background to a solo improvisa- tion. —OED - c o n t e n t s - List of figures xi Preface and Acknowledgments xiii introduction Gothic Riffs: songs in the Key of secularization 1 chapter 1 Gothic Mediations: shakespeare, the sentimental, and the secularization of Virtue 35 chapter 2 Rescue operas” and Providential Deism 74 chapter 3 Ghostly Visitants: the Gothic Drama and the coexistence of immanence and transcendence 103 chapter 4 Entr’acte. -

As Guest Some Pages Are Restricted

FRAG M ENTA G EN EA L O G I CA V L V O . I . PR I N TED AT TH E PR I VA TE PR ES S O F FR ED ER I C K A RTH U R C R I S P 1 90 1 CO N TEN TS . A A H UTOGR P S . PAGE H usse Thomas 7 y, 1 I nchi uin Ear 3 q , l Parde M atth 35 w, O m onde D uke of 34 r , Walsh Pei e 33 , rc 1 Wood Ri a d 3 , ch r H R H N T C U C O ES . ’ P an of som e of the a e s in the u a d of St. iles Cam e e l Gr v Ch rchy r G , b rw ll , S urrey DEEDS . is i to he Mano of fford uffo Adm s ons t r U , S lk ’ a ain M ler Husse s Pardon 1 6 8 . C pt y y , 9 ’ ’ D u e of O m ond s Ce ifi a e of Ed a d Husse s I nno en e 1 660 k r rt c t w r y c c , ’ ’ Ea I nchi uin 5 e ifi a e of Ed a d H usse s L o a 1 660 rl q C rt c t w r y y lty , Ma ia e A i es of o n Husse and L ae i ia u e 1 60 rr g rt cl J h y t t B rk , 7 M a ia e S e e m en of T omas H usse and I sm a L e ns 1 6 2 rr g ttl t h y y y , 5 ’ ’ Peirce Walsh s Articles of Ag reem e nt on his daug hte r s marriag e with Wa s 1 6 2 l h , 7 Pe i ion of E a d Husse 1 660 t t dw r y, TR N S I N L S &c . -

George Abbot 1562-1633 Archbishop of Canterbury

English Book Owners in the Seventeenth Century: A Work in Progress Listing How much do we really know about patterns and impacts of book ownership in Britain in the seventeenth century? How well equipped are we to answer questions such as the following?: What was a typical private library, in terms of size and content, in the seventeenth century? How does the answer to that question vary according to occupation, social status, etc? How does the answer vary over time? – how different are ownership patterns in the middle of the century from those of the beginning, and how different are they again at the end? Having sound answers to these questions will contribute significantly to our understanding of print culture and the history of the book more widely during this period. Our current state of knowledge is both imperfect, and fragmented. There is no directory or comprehensive reference source on seventeenth-century British book owners, although there are numerous studies of individual collectors. There are well-known names who are regularly cited in this context – Cotton, Dering, Pepys – and accepted wisdom as to collections which were particularly interesting or outstanding, but there is much in this area that deserves to be challenged. Private Libraries in Renaissance England and Books in Cambridge Inventories have developed a more comprehensive approach to a particular (academic) kind of owner, but they are largely focused on the sixteenth century. Sears Jayne, Library Catalogues of the English Renaissance, extends coverage to 1640, based on book lists found in a variety of manuscript sources. The Cambridge History of Libraries in Britain and Ireland (2006) contains much relevant information in this field, summarising existing scholarship, and references to this have been included in individual entries below where appropriate. -

GIPE-001848-Contents.Pdf

Dhananjayarao Gadgil Library III~III~~ mlll~~ I~IIIIIIII~IIIU GlPE-PUNE-OO 1848 CONSTITUTION AL HISTORY OF ENGLAND STUBBS 1Lonbon HENRY FROWDE OXFORD tTNIVERSITY PRESS WAREHOUSE AMEN CORNEl!. THE CONSTITUTIONAL mSTORY OF ENGLAND IN ITS ORIGIN AND DEtrLOP~'r BY WILLIAM STUBBS, D.D., BON. LL.D. BISHOP OF CHESTER VOL. III THIRD EDITIOlY @d.orlt AT Tag CLARENDON PRESS J( Deco LXXXIV [ A II rig"'" reserved. ] V'S;LM3 r~ 7. 3 /fyfS CONTENTS. CHAPTER XVIII. LANCASTER AND YORK. 299. Character of the period, p. 3. 300. Plan of the chapter, p. 5. 301. The Revolution of 1399, p. 6. 302. Formal recognition of the new Dynasty, p. 10. 303. Parliament of 1399, p. 15. 304. Conspiracy of the Earls, p. 26. 805. Beginning af difficulties, p. 37. 306. Parliament of 1401, p. 29. 807. Financial and poli tical difficulties, p. 35. 308. Parliament of 1402, 'p. 37. 309. Rebellion of Hotspur, p. 39. 310. Parliament of 14°40 P.42. 311. The Unlearned Parliament, P.47. 312. Rebellion of Northum berland, p. 49. 813. The Long Parliament of 1406, p. 54. 314. Parties fonned at Court, p. 59. 315. Parliament at Gloucester, 14°7, p. 61. 816. Arundel's administration, p. 63. 317. Parlia mont of 1410, p. 65. 318. Administration of Thomae Beaufort, p. 67. 319. Parliament of 14II, p. 68. 820. Death of Henry IV, p. 71. 821. Character of H'!I'l'Y. V, p. 74. 322. Change of ministers, p. 78. 823. Parliament of 1413, p. 79. 324. Sir John Oldcastle, p. 80. 325. -

Fifteenth Century Literary Culture with Particular

FIFTEENTH CENTURY LITERARY CULTURE WITH PARTICULAR* REFERENCE TO THE PATTERNS OF PATRONAGE, **FOCUSSING ON THE PATRONAGE OF THE STAFFORD FAMILY DURING THE FIFTEENTH CENTURY Elizabeth Ann Urquhart Submitted for the Degree of Ph.!)., September, 1985. Department of English Language, University of Sheffield. .1 ''CONTENTS page SUMMARY ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ill INTRODUCTION 1 CHAPTER 1 The Stafford Family 1066-1521 12 CHAPTER 2 How the Staffords could Afford Patronage 34 CHAPTER 3 The PrIce of Patronage 46 CHAPTER 4 The Staffords 1 Ownership of Books: (a) The Nature of the Evidence 56 (b) The Scope of the Survey 64 (c) Survey of the Staffords' Book Ownership, c. 1372-1521 66 (d) Survey of the Bourgchiers' Book Ownership, c. 1420-1523 209 CHAPTER 5 Considerations Arising from the Study of Stafford and Bourgchier Books 235 CHAPTER 6 A Brief Discussion of Book Ownership and Patronage Patterns amongst some of the Staffords' and Bourgchiers' Contemporaries 252 CONCLUSION A Piece in the Jigsaw 293 APPENDIX Duke Edward's Purchases of Printed Books and Manuscripts: Books Mentioned in some Surviving Accounts. 302 NOTES 306 TABLES 367 BIBLIOGRAPHY 379 FIFTEENTR CENTURY LITERARY CULTURE WITH PARTICULAR REFERENCE TO THE PATTERNS OF PATRONAGE, FOCUSSING ON THE PATRONAGE OF THE STAFFORD FAMILY DURING THE FIFTEENTH CENTURY. Elizabeth Ann Urquhart. Submitted for the Degree of Ph.D., September, 1985. Department of English Language, University of Sheffield. SUMMARY The aim of this study is to investigate the nature of the r61e played by literary patronage in fostering fifteenth century English literature. The topic is approached by means of a detailed exam- ination of the books and patronage of the Stafford family. -

Robert De STAFFORD Born

Robert De STAFFORD Born: 1216, Stafford Castle, Staffordshire, England Died: 4 Jun 1261 / 1282 / AFT 15 Jul 1287Notes: summoned to serve in Wales in 1260. Cokayne's "Complete Peerage" (STAFFORD, p.171-172) Father: Henry De STAFFORD Mother: Pernell De FERRERS Married: Alice CORBET (dau. of Thomas De Corbet and Isabel De Valletort) ABT 1240, Shropshire, England Children: 1. Alice De STAFFORD 2. Nicholas De STAFFORD 3. Isabella De STAFFORD 4. Amabil De STAFFORD Alice De STAFFORD Born: ABT 1240, Stafford, England Father: Robert De STAFFORD Mother: Alice CORBET Married: John De HOTHAM (Sir) Children: 1. John De HOTHAM 2. Peter De HOTHAM Isabella De STAFFORD Born: 1265 Father: Robert De STAFFORD Mother: Alice CORBET Married: William STAFFORD Children: 1. John STAFFORD Amabil De STAFFORD Father: Robert De STAFFORD Mother: Alice CORBET Married: Richard (Robert) RADCLIFFE Nicholas De STAFFORD Born: 1246, Stafford, England Died: 1 Aug 1287, Siege of Droselan Castle Notes: actively engaged against the Welsh, in the reign of King Edward I, and was killed before Droselan Castle. His manors included Offley, Schelbedon and Bradley, Staffordshire Father: Robert De STAFFORD Mother: Alice CORBET Married 1: Anne De LANGLEY Married 2: Eleanor De CLINTON Children: 1. Richard De STAFFORD 2. Edmund STAFFORD (1º B. Stafford) Edmund STAFFORD (1º B. Stafford) Born: 15 Jul 1272/3, Clifton, Staffordshire, England Died: 26 Aug 1308 Father: Nicholas De STAFFORD Mother: Eleanor De CLINTON Married: Margaret BASSETT (B. Stafford) BEF 1298, Drayton, Staffordshire, England Children: 1. Ralph STAFFORD (1º E. Stafford) 2. Richard STAFFORD (Sir Knight) 3. Margaret STAFFORD 4. William STAFFORD 5. -

COMMITTEE of PUBLIC ACCOUNTS Briefing for Posts & Hosts Visit To

Finansudvalget FIU alm. del - Bilag 146 Offentligt COMMITTEE OF PUBLIC ACCOUNTS www.parliament.uk/pac [email protected] Briefing for posts & hosts Visit to Copenhagen and Stockholm 20-24 May 2007 Membership of the Committee of Public Accounts The Committee consists of sixteen members, of whom a quorum is four. The members are nominated at the beginning of each Parliament (before December 1974, Members were nominated at the beginning of each Session) on the basis of a motion made by a Government minister, after consultation with the Opposition. Changes in membership are made from time to time during the Parliament, often because Members have become Ministers or front-bench opposition spokesmen. The party proportions of the Committee, like other committees, are the same as in the House, and at present this gives 9 Labour members, 5 Conservative members, and 2 minority party members (at present from the Liberal Democrats). One of the members is the Financial Secretary to the Treasury, who does not normally attend (Rt Hon John Healey MP). The Committee chooses its own chairman, traditionally an Opposition member, usually with previous experience as a Treasury minister. Divisions in the Committee are very rare, generally occurring less than once a year. The current membership of the Committee is as follows: Mr Edward Leigh MP (Chairman) (Conservative, Gainsborough) Mr Richard Bacon MP (Conservative, South Norfolk) Annette Brooke MP (Liberal Democrat, Mid Dorset and Poole North Mr Greg Clarke MP (Conservative, Tunbridge Wells) Rt Hon David -

Exeter Register Cover 2007

EXETER COLLEGE ASSOCIATION Register 2007 Contents From the Rector 6 From the President of the MCR 10 From the President of the JCR 12 Alan Raitt by David Pattison 16 William Drower 18 Arthur Peacocke by John Polkinghorne 20 Hugh Kawharu by Amokura Kawharu 23 Peter Crill by Godfray Le Quesne 26 Rodney Hunter by Peter Stone 28 David Phillips by Jan Weryho 30 Phillip Whitehead by David Butler 34 Ned Sherrin by Tony Moreton 35 John Maddicott by Paul Slack and Faramerz Dabhoiwala 37 Gillian Griffiths by Richard Vaughan-Jones 40 Exeter College Chapel by Helen Orchard 42 Sermon to Celebrate the Restoration of the Chapel by Helen Orchard 45 There are Mice Throughout the Library by Helen Spencer 47 The Development Office 2006-7 by Katrina Hancock 50 The Association and the Register by Christopher Kirwan 51 A Brief History of the Exeter College Development Board by Mark Houghton-Berry 59 Roughly a Hundred Years Ago: A Law Tutor 61 Aubrey on Richard Napier (and his Nephew) 63 Quantum Computing by Andrew M. Steane 64 Javier Marías by Gareth Wood 68 You Have to Be Lucky by Rip Bulkeley 72 Memorabilia by B.L.D. Phillips 75 Nevill Coghill, a TV programme, and the Foggy Foggy Dew by Tony Moreton 77 The World’s First Opera by David Marler 80 A Brief Encounter by Keith Ferris 85 College Notes and Queries 86 The Governing Body 89 Honours and Appointments 90 Publications 91 Class Lists in Honour Schools and Honour Moderations 2007 94 Distinctions in Moderations and Prelims 2007 96 1 Graduate Degrees 2007 97 College Prizes 99 University Prizes 100 Graduate Freshers 2007 101 Undergraduate Freshers 2007 102 Deaths 105 Marriages 107 Births 108 Notices 109 2 Editor Christopher Kirwan was Fellow and Lecturer in Philosophy from 1960 to 2000. -

1999 Election Candidates | European Parliament Information Office in the United Kin

1999 Election Candidates | European Parliament Information Office in the United Kin ... Page 1 of 10 UK Office of the European Parliament Home > 1999 > 1999 Election Candidates Candidates The list of candidates was based on the information supplied by Regional Returning Officers at the close of nominations on 13 May 2004. Whilst every care was taken to ensure that this information is accurate, we cannot accept responsibility for any omissions or inaccuracies or for any consequences that may result. Voters in the UK's twelve EU constituencies will elect 78 MEPs. The distribution of seats is as follows: Eastern: 7 East Midlands: 6 London: 9 North East: 3 North West: 9 South East: 10 South West: 7 West Midlands: 7 Yorkshire and the Humber: 6 Scotland: 7 Wales: 4 Northern Ireland: 3 Eastern LABOUR CONSERVATIVE 1. Eryl McNally, MEP 1. Robert Sturdy, MEP 2. Richard Howitt, MEP 2. Christopher Beazley 3. Clive Needle, MEP 3. Bashir Khanbhai 4. Peter Truscott, MEP 4. Geoffrey Van Orden 5. David Thomas, MEP 5. Robert Gordon 6. Virginia Bucknor 6. Kay Twitchen 7. Beth Kelly 7. Sir Graham Bright 8. Ruth Bagnall 8. Charles Rose LIBERAL DEMOCRAT GREEN 1. Andrew Duff 1. Margaret Elizabeth Wright 2. Rosalind Scott 2. Marc Scheimann 3. Robert Browne 3. Eleanor Jessy Burgess 4. Lorna Spenceley 4. Malcolm Powell 5. Chris White 5. James Abbott 6. Charlotte Cane 6. Jennifer Berry 7. Paul Burall 7. Angela Joan Thomson 8. Rosalind Gill 8. Adrian Holmes UK INDEPENDENCE PRO EURO CONSERVATIVE PARTY 1. Jeffrey Titford 1. Paul Howell 2. Bryan Smalley 2. -

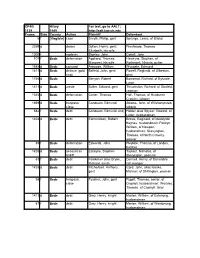

Cp40no1139cty.Pdf

CP40/ Hilary For text, go to AALT: 1139 1549 http://aalt.law.uh.edu Frame Side County Action Plaintiff Defendant 5 f [illegible] case Smyth, Phillip, gent Sprynge, Lewis, of Bristol 2259 d dower Dyllon, Henry, gent; Prestwode, Thomas Elizabeth, his wife 1000 f replevin Stonley, John Cottell, John 101 f Beds defamation Appliard, Thomas; Hawkyns, Stephen, of Margaret, his wife Rothewell, Nhants, pulter 1685 d Beds concord Atwoode, William Wyngate, Edmund 1411 d Beds detinue (gold Belfeld, John, gent Powell, Reginald, of Olbeston, ring) gent 1746 d Beds Benyon, Robert Bowstrad, Richard, of Byscote, Luton 1411 d Beds waste Butler, Edward, gent Thruckston, Richard, of Stotfeld, yeoman 1345 d Beds defamation Carter, Thomas Hall, Thomas, of Husburne Crawley, laborer 1869 d Beds trespass: Conquest, Edmund Adams, John, of Wilshampsted, close laborer 582 f Beds debt Conquest, Edmund, esq Helder alias Spycer, Edward, of Luton, husbandman 1428 d Beds debt Edmundson, Robert Browe, Reginald, of Meddylton Keynes, husbandman; Pokkyn, William, of Newport, husbandman; Skevyngton, Thomas, of North Crawley, weaver 85 f Beds defamation Edwards, John Pleyfote, Thomas, of London, butcher 1426 d Beds account as Estwyke, Stephen Taylour, Nicholas, of bailiff Stevyngton, yeoman 83 f Beds debt Fawkener alias Bryan, Dennell, Henry, of Dunstable, Richard, smith fish monger 1428 d Beds debt Fitzherbart, Anthony, Izard, John, alias Isaake, gent Michael, of Shitlington, yeoman 98 f Beds trespass: Fyssher, John, gent Pygett, Thomas, senior, of close Clophyll, husbandman; -

Exeter Excelling a Celebration of Success Message from the Rector Professor Sir Rick Trainor

EXETER EXCELLING A CELEBRATION OF SUCCESS MESSAGE FROM THE RECTOR PROFESSOR SIR RICK TRAINOR leap forwards in securing xeter’s future It is with great honour and pleasure that I can announce, with gratitude to the whole Exeter community, that we have exceeded our goal of raising £45 million over the last 10 years. The Exeter Excelling campaign was launched in 2006 and, over the period leading up to our 700th anniversary in 2014 – and a little beyond – we have received support on a scale that has never before been achieved by an Oxford college. With over 4,000 alumni making a gift in this period, and support also from parents, friends, Fellows, staff and even current students, we have leapt forwards in securing Exeter’s future as it enters its eighth century. Your support has created an entirely new quadrangle for this and future generations of Exonians – the biggest single expansion of the College since its earliest years. In addition you have secured tutorial teaching and made study at Oxford an affordable option for the brightest young minds in the UK and around the world. Thank you for what you’ve done as a member of this family: for your friendship, your support, your guidance, and most of all for your passion in seeing Exeter excel. In celebrating these achievements, I know you will join with me in giving substantial credit and heartfelt thanks to Rector Frances Cairncross whose vision and leadership brought this Campaign, and indeed Cohen Quad, into existence. I have very much inherited the success that her endeavours, for which we are all grateful, have brought about.