The Role of Local Perceptions in the Marketing of Rural Areas

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Hove and the Great

H o v e a n d t h e Gre a t Wa r A RECORD AND A R E VIE W together with the R oll o f Ho n o u r and Li st o f D i sti n c tio n s By H . M . WALBROOK ’ Im ied una er toe a u fbority cftfie Hov e Wa r Memorial Com m ittee Hove Sussex Th e Cliftonville Press 1 9 2 0 H o v e a n d t h e Gre a t Wa r A RECORD AND A REVIEW together with the R o ll o f Ho n o u r and Li st o f D i sti n c tio n s BY H . M . WALBROOK ’ In ned u nner toe a u tbority oftbe Have Wa r Memoria l Comm ittee Hove Sussex The Cliftonville Press 1 9 2 0 the Powers militant That stood for Heaven , in mighty quadrate joined Of union irresistible , moved on In silence their bright legions, to the sound Of instrumental harmony, that breathed Heroic ardour to adventurous deeds, Under their godlike leaders, in the cause O f ” God and His Messiah . J oan Milton. Fore word HAVE been asked to write a “ Foreword to this book ; personally I think the book speaks for itself. Representations have been ’ made from time to time that a record o fHove s share in the Great War should be published, and the idea having been put before the public meeting of the inhabitants called in April last to consider the question of a War Memorial , the publication became part, although a very minor part, of the scheme . -

FY12 Statbook SWK1 Dresden V02.Xlsx Bylea Tuitions Paid in FY12 by Vermont Districts to Out-Of-State Page 2 Public and Independent Schools for Regular Education

Tuitions Paid in FY12 by Vermont Districts to Out-of-State Page 1 Public and Independent Schools for Regular Education LEA id LEA paying tuition S.U. Grade School receiving tuition City State FTE Tuition Tuition Paid Level 281.65 Rate 3,352,300 T003 Alburgh Grand Isle S.U. 24 7 - 12 Northeastern Clinton Central School District Champlain NY 19.00 8,500 161,500 Public T021 Bloomfield Essex North S.U. 19 7 - 12 Colebrook School District Colebrook NH 6.39 16,344 104,498 Public T021 Bloomfield 19 7 - 12 North Country Charter Academy Littleton NH 1.00 9,213 9,213 Public T021 Bloomfield 19 7 - 12 Northumberland School District Groveton NH 5.00 12,831 64,155 Public T035 Brunswick Essex North S.U. 19 7 - 12 Colebrook School District Colebrook NH 1.41 16,344 23,102 Public T035 Brunswick 19 7 - 12 Northumberland School District Groveton NH 1.80 13,313 23,988 Public T035 Brunswick 19 7 - 12 White Mountain Regional School District Whitefiled NH 1.94 13,300 25,851 Public T048 Chittenden Rutland Northeast S.U. 36 7 - 12 Kimball Union Academy Meriden NH 1.00 12,035 12,035 Private T048 Chittenden 36 7 - 12 Lake Mary Preparatory School Lake Mary FL 0.50 12,035 6,018 Private T054 Coventry North Country S.U. 31 7 - 12 Stanstead College Stanstead QC 3.00 12,035 36,105 Private T056 Danby Bennington - Rutland S.U. 06 7 - 12 White Mountain School Bethlehem NH 0.83 12,035 9,962 Private T059 Dorset Bennington - Rutland S.U. -

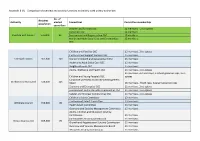

Comparison of Overview and Scrutiny Functions at Similarly Sized Unitary Authorities

Appendix B (4) – Comparison of overview and scrutiny functions at similarly sized unitary authorities No. of Resident Authority elected Committees Committee membership population councillors Children and Families OSC 12 members + 2 co-optees Corporate OSC 12 members Cheshire East Council 378,800 82 Environment and Regeneration OSC 12 members Health and Adult Social Care and Communities 15 members OSC Children and Families OSC 15 members, 2 co-optees Customer and Support Services OSC 15 members Cornwall Council 561,300 123 Economic Growth and Development OSC 15 members Health and Adult Social Care OSC 15 members Neighbourhoods OSC 15 members Adults, Wellbeing and Health OSC 21 members, 2 co-optees 21 members, 4 church reps, 3 school governor reps, 2 co- Children and Young People's OSC optees Corporate Overview and Scrutiny Management Durham County Council 523,000 126 Board 26 members, 4 faith reps, 3 parent governor reps Economy and Enterprise OSC 21 members, 2 co-optees Environment and Sustainable Communities OSC 21 members, 2 co-optees Safeter and Stronger Communities OSC 21 members, 2 co-optees Children's Select Committee 13 members Environment Select Committee 13 members Wiltshere Council 496,000 98 Health Select Committee 13 members Overview and Scrutiny Management Committee 15 members Adults, Children and Education Scrutiny Commission 11 members Communities Scrutiny Commission 11 members Bristol City Council 459,300 70 Growth and Regeneration Scrutiny Commission 11 members Overview and Scrutiny Management Board 11 members Resources -

Introductions to Heritage Assets: Hermitages

Hermitages Introductions to Heritage Assets Summary Historic England’s Introductions to Heritage Assets (IHAs) are accessible, authoritative, illustrated summaries of what we know about specific types of archaeological site, building, landscape or marine asset. Typically they deal with subjects which have previously lacked such a published summary, either because the literature is dauntingly voluminous, or alternatively where little has been written. Most often it is the latter, and many IHAs bring understanding of site or building types which are neglected or little understood. This IHA provides an introduction to hermitages (places which housed a religious individual or group seeking solitude and isolation). Six types of medieval hermitage have been identified based on their siting: island and fen; forest and hillside; cave; coast; highway and bridge; and town. Descriptions of solitary; cave; communal; chantry; and lighthouse hermitages; and town hermits and their development are included. Hermitages have a large number of possible associations and were fluid establishments, overlapping with hospices, hospitals, monasteries, nunneries, bridge and chantry chapels and monastic retreats. A list of in-depth sources on the topic is suggested for further reading. This document has been prepared by Kate Wilson and edited by Joe Flatman and Pete Herring. It is one of a series of 41 documents. This edition published by Historic England October 2018. All images © Historic England unless otherwise stated. Please refer to this document as: Historic England 2018 Hermitages: Introductions to Heritage Assets. Swindon. Historic England. It is one is of several guidance documents that can be accessed at HistoricEngland.org.uk/listing/selection-criteria/scheduling-selection/ihas-archaeology/ Front cover The outside of the medieval hermitage at Warkworth, Northumberland. -

Northumberland Coast Designation History

DESIGNATION HISTORY SERIES NORTHUMBERLAND COAST AONB Ray Woolmore BA(Hons), MRTPI, FRGS December 2004 NORTHUMBERLAND COAST AONB Origin 1. The Government first considered the setting up of National Parks and other similar areas in England and Wales when, in 1929, the Prime Minister, Ramsay Macdonald, established a National Park Committee, chaired by the Rt. Hon. Christopher Addison MP, MD. The “Addison” Committee reported to Government in 1931, and surprisingly, the Report1 showed that no consideration had been given to the fine coastline of Northumberland, neither by witnesses to the Committee, nor by the Committee itself. The Cheviot, and the moorland section of the Roman Wall, had been put forward as National Parks by eminent witnesses, but not the unspoilt Northumberland coastline. 2. The omission of the Northumberland coastline from the 1931 Addison Report was redressed in 1945, when John Dower, an architect/planner, commissioned by the Wartime Government “to study the problems relating to the establishment of National Parks in England and Wales”, included in his report2, the Northumberland Coast (part) in his Division C List: “Other Amenity Areas NOT suggested as National Parks”. Dower had put forward these areas as areas which although unlikely to be found suitable as National Parks, did deserve and require special concern from planning authorities “in order to safeguard their landscape beauty, farming use and wildlife, and to increase appropriately their facilities for open-air recreation”. A small-scale map in the Report, (Map II page 12), suggests that Dower’s Northumberland Coast Amenity Area stretched southwards from Berwick as a narrow coastal strip, including Holy Island, to Alnmouth. -

Tuitions Paid in FY2013 by Vermont Districts to Out-Of-State Public And

Tuitions Paid in FY2013 by Vermont Districts to Out-of-State Page 1 Public and Independent Schools for Regular Education LEA id LEA paying tuition S.U. Grade School receiving tuition City State FTE Tuition Tuition Paid Level 331.67 Rate 3,587,835 T003 Alburgh Grand Isle S.U. 24 Sec Clinton Community College Champlain NY 1.00 165 165 College T003 Alburgh 24 Sec Northeastern Clinton Central School District Champlain NY 14.61 9,000 131,481 Public T003 Alburgh 24 Sec Paul Smith College Paul Smith NY 2.00 120 240 College T010 Barnet Caledonia Central S.U. 09 Sec Haverhill Cooperative Middle School Haverhill NH 0.50 14,475 7,238 Public T021 Bloomfield Essex North S.U. 19 Sec Colebrook School District Colebrook NH 9.31 16,017 149,164 Public T021 Bloomfield 19 Sec Groveton High School Northumberland NH 3.96 14,768 58,547 Public T021 Bloomfield 19 Sec Stratford School District Stratford NH 1.97 13,620 26,862 Public T035 Brunswick Essex North S.U. 19 Sec Colebrook School District Colebrook NH 1.50 16,017 24,026 Public T035 Brunswick 19 Sec Northumberland School District Groveton NH 2.00 14,506 29,011 Public T035 Brunswick 19 Sec White Mountain Regional School District Whitefiled NH 2.38 14,444 34,409 Public T036 Burke Caledonia North S.U. 08 Sec AFS-USA Argentina 1.00 12,461 12,461 Private T041 Canaan Essex North S.U. 19 Sec White Mountain Community College Berlin NH 39.00 150 5,850 College T048 Chittenden Rutland Northeast S.U. -

Northumberland and Durham Family History Society Unwanted

Northumberland and Durham Family History Society baptism birth marriage No Gsurname Gforename Bsurname Bforename dayMonth year place death No Bsurname Bforename Gsurname Gforename dayMonth year place all No surname forename dayMonth year place Marriage 933ABBOT Mary ROBINSON James 18Oct1851 Windermere Westmorland Marriage 588ABBOT William HADAWAY Ann 25 Jul1869 Tynemouth Marriage 935ABBOTT Edwin NESS Sarah Jane 20 Jul1882 Wallsend Parrish Church Northumbrland Marriage1561ABBS Maria FORDER James 21May1861 Brooke, Norfolk Marriage 1442 ABELL Thirza GUTTERIDGE Amos 3 Aug 1874 Eston Yorks Death 229 ADAM Ellen 9 Feb 1967 Newcastle upon Tyne Death 406 ADAMS Matilda 11 Oct 1931 Lanchester Co Durham Marriage 2326ADAMS Sarah Elizabeth SOMERSET Ernest Edward 26 Dec 1901 Heaton, Newcastle upon Tyne Marriage1768ADAMS Thomas BORTON Mary 16Oct1849 Coughton Northampton Death 1556 ADAMS Thomas 15 Jan 1908 Brackley, Norhants,Oxford Bucks Birth 3605 ADAMS Sarah Elizabeth 18 May 1876 Stockton Co Durham Marriage 568 ADAMSON Annabell HADAWAY Thomas William 30 Sep 1885 Tynemouth Death 1999 ADAMSON Bryan 13 Aug 1972 Newcastle upon Tyne Birth 835 ADAMSON Constance 18 Oct 1850 Tynemouth Birth 3289ADAMSON Emma Jane 19Jun 1867Hamsterley Co Durham Marriage 556 ADAMSON James Frederick TATE Annabell 6 Oct 1861 Tynemouth Marriage1292ADAMSON Jane HARTBURN John 2Sep1839 Stockton & Sedgefield Co Durham Birth 3654 ADAMSON Julie Kristina 16 Dec 1971 Tynemouth, Northumberland Marriage 2357ADAMSON June PORTER William Sidney 1May 1980 North Tyneside East Death 747 ADAMSON -

Municipal Onlot Sewage Service Depiction

NC Region – Municipal Onlot Sewage Service Depiction The following map depicts the most current types of municipal onlot sewage service for the Northcentral region (updated 3/1/15). Municipal Onlot Sewage Service Depiction Individual Municipal Service Area Joint Local Agency Service Area Designated Joint Local Agency Service Area County Boundaries NC Region Municipal Onlot Sewage Service Areas MUNICIPALITY COUNTY JOINT LOCAL AGENCY NAME Abbott Township Potter Adams Township Snyder Snyder Co Sewage Code Enforcement Committee Alba Borough Bradford Bradford County Sanitation Committee Albany Township Bradford Bradford County Sanitation Committee Allegany Township Potter Allison Township Clinton Anthony Township Lycoming Anthony Township Montour Armenia Township Bradford Bradford County Sanitation Committee Armstrong Township Lycoming Asylum Township Bradford Bradford County Sanitation Committee Athens Borough Bradford Bradford County Sanitation Committee Athens Township Bradford Bradford County Sanitation Committee Austin Borough Potter Avis Borough Clinton Bald Eagle Township Clinton Bastress Township Lycoming Beaver Township Columbia Beaver Township Snyder Beavertown Borough Snyder Beccaria Township Clearfield Clearfield County Sewage Agency Beech Creek Borough Clinton Beech Creek Township Clinton Bell Township Clearfield Clearfield County Sewage Agency Bellefonte Borough Centre Benner Township Centre Benton Borough Columbia Columbia Co Sanitary Administration Committee Benton Township Columbia Columbia Co Sanitary Administration Committee -

Harrisburg-Lancaster-Lebanon-York, PA

TV Station WGAL · Analog Channel 8, DTV Channel 8 · Lancaster, PA Expected Change In Coverage: Granted Construction Permit CP (solid): 7.50 kW ERP at 419 m HAAT, Network: NBC vs. Analog (dashed): 110 kW ERP at 419 m HAAT, Network: NBC Market: Harrisburg-Lancaster-Lebanon-York, PA Lycoming Clinton Montour Columbia Luzerne Union PA-5 PA-11 Monroe Centre PA-10 Carbon Northumberland Snyder Schuylkill Northampton PA-15 Mifflin Lehigh Allentown Juniata Dauphin PA-17 PA-8 Bucks Perry Berks Lebanon Reading PA-13 Huntingdon Harrisburg Montgomery PA-9 Cumberland PA-6 Lancaster A8 D8 Lancaster Chester PA-16 PA-19 York PA-7 Franklin York Delaware Adams Chester GloucesterNJ-1 Wilmington New Castle MD-1 Washington Cecil Salem Carroll Harford MD-6 Berkeley Baltimore NJ-2 Frederick MD-1 MD-2 Frederick Cumberland WV-2 MD-3 Jefferson Baltimore MD-4MD-7 Kent Howard MD-2 DE MD-3 VA-10 Montgomery MD-1 Kent Loudoun Gaithersburg MD-8 Anne Arundel Queen Anne's 2008 Hammett & Edison, Inc.Prince George's MD-1 Caroline MD-5 10 MI 0 10 20 30 40 50 60 40 20 0 KM 20 Coverage gained after DTV transition (no symbol) No change in coverage Coverage lost but still served by same network WGAL CP Station WGCB-TV · Analog Channel 49, DTV Channel 30 · Red Lion, PA Expected Change In Coverage: Licensed Operation Licensed (solid): 500 kW ERP at 174 m HAAT vs. Analog (dashed): 646 kW ERP at 177 m HAAT Market: Harrisburg-Lancaster-Lebanon-York, PA Montour Luzerne Union Columbia PA-11 Monroe Centre PA-10 Carbon PA-5 Northumberland Snyder Schuylkill Northampton Mifflin PA-15 Lehigh -

VIRGINIA ZIP CITY COUNTY 22206 Arlington Accomack 22432 Burgess

VIRGINIA ZIP CITY COUNTY 22206 Arlington Accomack 22432 Burgess Northumberland 22435 Callao Northumberland 22436 Caret Essex 22437 Center Cross Essex 22438 Champlain Essex 22442 Coles Point Westmoreland 22443 Colonial Beach Westmoreland 22454 Dunnsville Essex 22456 Edwardsville Northumberland 22460 Farnham Richmond 22469 Hague Westmoreland 22472 Haynesville Richmond 22473 Heathsville Lancaster 22476 Hustle Essex 22480 Irvington Lancaster 22482 Kilmarnock Lancaster 22485 King George Westmoreland 22488 Kinsale Westmoreland 22503 Lancaster Lancaster 22504 Laneview Essex 22507 Lively Lancaster 22509 Loretto Essex 22511 Lottsburg Northumberland 22513 Merry Point Lancaster 22517 Mollusk Lancaster 22520 Montross Richmond 22523 Morattico Lancaster 22524 Mount Holly Westmoreland 22528 Nuttsville Lancaster 22529 Oldhams Westmoreland 22530 Ophelia Northumberland 22539 Reedville Northumberland 22548 Sharps Richmond 22558 Stratford Westmoreland 22560 Tappahannock Essex 22570 Village Richmond 22572 Warsaw Richmond 22576 Weems Lancaster 22577 Sandy Point Westmoreland 22578 White Stone Lancaster 22579 Wicomico Church Northumberland 22581 Zacata Westmoreland 22728 Midland Accomack 23001 Achilles Gloucester 23003 Ark Gloucester 23018 Bena Gloucester 23021 Bohannon Mathews 23023 Bruington Essex 23025 Cardinal Mathews 23031 Christchurch Middlesex 23032 Church View Middlesex 23035 Cobbs Creek Mathews 23043 Deltaville Middlesex 23045 Diggs Mathews 23050 Dutton Gloucester 23056 Foster Mathews 23061 Gloucester Gloucester 23062 Gloucester Point Gloucester 23064 -

6170 the London Gazette, 17 November, 1953

6170 THE LONDON GAZETTE, 17 NOVEMBER, 1953 , County of London—Geoffrey Cecil Ryves Eley, Esq., Major The Honourable James Perrott Philipps, C.B.E., of 1, Pembroke Villas, W.8. T.D., of Dalham Hall, Newmarket. William Antony Acton, Esq., of 115, Eaton Lieut-Colonel Brian Sherlock Gooch, D.S.O., of Square, London, S.W.I. Tannington Hall, Woodbridge. Sir Charles Jocelyn Hambro, K.B.E., M.C., of Surrey—Henry Michael Gordon Clark, Esq., of The 72, North Gate, Regents Park, London, N.W.8. Old Cottage, Mickleham, Dorking, Surrey. Middlesex—William Reginald Clemens, Esq., of 90, Colonel The Honourable Charles Guy Cubitt, Beaufort Park, Hampstead Garden Suburb, D.S.O., T.D., of High Barn, Effingham, Surrey. N.W.ll. Colonel Sir Ambrose Keevil, C.B.E., M.C., of Charles William Skinner, Esq., of 124, Powys Bayards, Warlingham, Surrey. Lane, Palmers Green, N.13. Sussex—Cornelius William Shelford, Esq., of Chailey Arthur Hillier, Esq., O.B.E., of 31, Arlington Place, near Lewes. House, Arlington Street, S.W.I. Gavin Astor, Esq., of Wickenden Manor, Sharp- Monmouthshire—David Ronald1 Phillips, Esq., of thorne, near East Grinstead. Oakdene, Dewsland Park, Newport. Lieut-Colonel Henry Swanston Eeles, O.B.E., Lieut.-Colonel John David Griffiths, of The M.C., T.D., of Sandyden House, Mark Cross, Cottage, Lower Machen. Tunbridge Wells. Lieut.-Colonel Edward Roderick Hill, of St. Warwickshire—Brigadier Ralph Charles Matthews, Arvans Court, Chepstow. M.C., of Toft House, Dunchurch, near Rugby. Norfolk—Major Charles Fellowes, of Shotesham George Tom Mills, Esq., of Park House, Park Park, Norwich. -

Municipality of Brighton 35 Alice Street Committee of the Whole Meeting

MUNICIPALITY OF BRIGHTON 35 ALICE STREET COMMITTEE OF THE WHOLE MEETING MEETING DATE: June 9 2008 TIME: 6:30 P.M. - AGENDA - 1. CALL TO ORDER — Chairperson — Mike Vandertoorn 2. APPROVAL OF AGENDA - THEREOF 3. DECLARATIONS OF PECUNIARY INTERESTS & GENERAL NATURE 4. DELEGATIONS — Study 1. Bill Pyatt , CAO Northumberland County Policing The Police Service board members will be in attendance at the invitation of Council to participate in this portion of the agenda 2. Peter Cony — PSB Chair 5. DEPARTMENT REPORTS - 1. Parks & Recreation - Jim Millar a) OW Grand Opening of Refurbished Ball Diamonds June it @ loam 2. Public Safety — Fire Chief Harry Tackaberry a) Incident Type Report — 2008 & 2007 b) Officers Meeting — June 3/08 c) Thank You Letter to Heart & Stroke Foundation re: 3 Defibrillators 3. Planning & Development Services — Ken Hurford a) Building Permit Record May/08 b) By-law Enforcement Record May/08 4. Public Works & Environmental Services — Jim Phillips a) 401 Signage Illumination b) Municipal Service Club Signs c) Herrington Pit Agreement 5. CAO/Clerk — Gayle Frost a) Waterfront Master Plan Request to CFDC to reallocate monies approved for the Youth Intern Program 6. CORRESPONDENCE - None 7. MEMBER REPORTS 8. QUESTION PERIOD 9. ADJOURNMENT Agenda 1. Brief Review of the Study Process and Findings to November2007 2. Results of Supplementary Investigations Dec. 2007 to April 2008 3. First and Five Year Costs 4 Decision Making Process —--- -a — —- Study Objectives ODtiOns Considered Carry out accurate cost comparisons: 1. OPP The existing policing arrangements 2. Cobourg expands force and polices entire County Versus 3. Port Hope expands force and polices entire County A single County-wide policing model Study Management Study Process • Steering Committee comprised of • 5 Phases - 7 Mayors (County Council) • Preparatory work —2005 - 7 Local chief Administrative Officers • Consultant selection — December 2005 - 1 County of Northumberland G.A.O.