Digital Signals - Sampling and Quantization

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Mathematical Basics of Bandlimited Sampling and Aliasing

Signal Processing Mathematical basics of bandlimited sampling and aliasing Modern applications often require that we sample analog signals, convert them to digital form, perform operations on them, and reconstruct them as analog signals. The important question is how to sample and reconstruct an analog signal while preserving the full information of the original. By Vladimir Vitchev o begin, we are concerned exclusively The limits of integration for Equation 5 T about bandlimited signals. The reasons are specified only for one period. That isn’t a are both mathematical and physical, as we problem when dealing with the delta func- discuss later. A signal is said to be band- Furthermore, note that the asterisk in Equa- tion, but to give rigor to the above expres- limited if the amplitude of its spectrum goes tion 3 denotes convolution, not multiplica- sions, note that substitutions can be made: to zero for all frequencies beyond some thresh- tion. Since we know the spectrum of the The integral can be replaced with a Fourier old called the cutoff frequency. For one such original signal G(f), we need find only the integral from minus infinity to infinity, and signal (g(t) in Figure 1), the spectrum is zero Fourier transform of the train of impulses. To the periodic train of delta functions can be for frequencies above a. In that case, the do so we recognize that the train of impulses replaced with a single delta function, which is value a is also the bandwidth (BW) for this is a periodic function and can, therefore, be the basis for the periodic signal. -

Efficient Supersampling Antialiasing for High-Performance Architectures

Efficient Supersampling Antialiasing for High-Performance Architectures TR91-023 April, 1991 Steven Molnar The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill Department of Computer Science CB#3175, Sitterson Hall Chapel Hill, NC 27599-3175 This work was supported by DARPA/ISTO Order No. 6090, NSF Grant No. DCI- 8601152 and IBM. UNC is an Equa.l Opportunity/Affirmative Action Institution. EFFICIENT SUPERSAMPLING ANTIALIASING FOR HIGH PERFORMANCE ARCHITECTURES Steven Molnar Department of Computer Science University of North Carolina Chapel Hill, NC 27599-3175 Abstract Techniques are presented for increasing the efficiency of supersampling antialiasing in high-performance graphics architectures. The traditional approach is to sample each pixel with multiple, regularly spaced or jittered samples, and to blend the sample values into a final value using a weighted average [FUCH85][DEER88][MAMM89][HAEB90]. This paper describes a new type of antialiasing kernel that is optimized for the constraints of hardware systems and produces higher quality images with fewer sample points than traditional methods. The central idea is to compute a Poisson-disk distribution of sample points for a small region of the screen (typically pixel-sized, or the size of a few pixels). Sample points are then assigned to pixels so that the density of samples points (rather than weights) for each pixel approximates a Gaussian (or other) reconstruction filter as closely as possible. The result is a supersampling kernel that implements importance sampling with Poisson-disk-distributed samples. The method incurs no additional run-time expense over standard weighted-average supersampling methods, supports successive-refinement, and can be implemented on any high-performance system that point samples accurately and has sufficient frame-buffer storage for two color buffers. -

Super-Sampling Anti-Aliasing Analyzed

Super-sampling Anti-aliasing Analyzed Kristof Beets Dave Barron Beyond3D [email protected] Abstract - This paper examines two varieties of super-sample anti-aliasing: Rotated Grid Super- Sampling (RGSS) and Ordered Grid Super-Sampling (OGSS). RGSS employs a sub-sampling grid that is rotated around the standard horizontal and vertical offset axes used in OGSS by (typically) 20 to 30°. RGSS is seen to have one basic advantage over OGSS: More effective anti-aliasing near the horizontal and vertical axes, where the human eye can most easily detect screen aliasing (jaggies). This advantage also permits the use of fewer sub-samples to achieve approximately the same visual effect as OGSS. In addition, this paper examines the fill-rate, memory, and bandwidth usage of both anti-aliasing techniques. Super-sampling anti-aliasing is found to be a costly process that inevitably reduces graphics processing performance, typically by a substantial margin. However, anti-aliasing’s posi- tive impact on image quality is significant and is seen to be very important to an improved gaming experience and worth the performance cost. What is Aliasing? digital medium like a CD. This translates to graphics in that a sample represents a specific moment as well as a Computers have always strived to achieve a higher-level specific area. A pixel represents each area and a frame of quality in graphics, with the goal in mind of eventu- represents each moment. ally being able to create an accurate representation of reality. Of course, to achieve reality itself is impossible, At our current level of consumer technology, it simply as reality is infinitely detailed. -

Efficient Multidimensional Sampling

EUROGRAPHICS 2002 / G. Drettakis and H.-P. Seidel Volume 21 (2002 ), Number 3 (Guest Editors) Efficient Multidimensional Sampling Thomas Kollig and Alexander Keller Department of Computer Science, Kaiserslautern University, Germany Abstract Image synthesis often requires the Monte Carlo estimation of integrals. Based on a generalized con- cept of stratification we present an efficient sampling scheme that consistently outperforms previous techniques. This is achieved by assembling sampling patterns that are stratified in the sense of jittered sampling and N-rooks sampling at the same time. The faster convergence and improved anti-aliasing are demonstrated by numerical experiments. Categories and Subject Descriptors (according to ACM CCS): G.3 [Probability and Statistics]: Prob- abilistic Algorithms (including Monte Carlo); I.3.2 [Computer Graphics]: Picture/Image Generation; I.3.7 [Computer Graphics]: Three-Dimensional Graphics and Realism. 1. Introduction general concept of stratification than just joining jit- tered and Latin hypercube sampling. Since our sam- Many rendering tasks are given in integral form and ples are highly correlated and satisfy a minimum dis- usually the integrands are discontinuous and of high tance property, noise artifacts are attenuated much 22 dimension, too. Since the Monte Carlo method is in- more efficiently and anti-aliasing is improved. dependent of dimension and applicable to all square- integrable functions, it has proven to be a practical tool for numerical integration. It relies on the point 2. Monte Carlo Integration sampling paradigm and such on sample placement. In- The Monte Carlo method of integration estimates the creasing the uniformity of the samples is crucial for integral of a square-integrable function f over the s- the efficiency of the stochastic method and the level dimensional unit cube by of noise contained in the rendered images. -

Signal Sampling

FYS3240 PC-based instrumentation and microcontrollers Signal sampling Spring 2017 – Lecture #5 Bekkeng, 30.01.2017 Content – Aliasing – Sampling – Analog to Digital Conversion (ADC) – Filtering – Oversampling – Triggering Analog Signal Information Three types of information: • Level • Shape • Frequency Sampling Considerations – An analog signal is continuous – A sampled signal is a series of discrete samples acquired at a specified sampling rate – The faster we sample the more our sampled signal will look like our actual signal Actual Signal – If not sampled fast enough a problem known as aliasing will occur Sampled Signal Aliasing Adequately Sampled SignalSignal Aliased Signal Bandwidth of a filter • The bandwidth B of a filter is defined to be between the -3 dB points Sampling & Nyquist’s Theorem • Nyquist’s sampling theorem: – The sample frequency should be at least twice the highest frequency contained in the signal Δf • Or, more correctly: The sample frequency fs should be at least twice the bandwidth Δf of your signal 0 f • In mathematical terms: fs ≥ 2 *Δf, where Δf = fhigh – flow • However, to accurately represent the shape of the ECG signal signal, or to determine peak maximum and peak locations, a higher sampling rate is required – Typically a sample rate of 10 times the bandwidth of the signal is required. Illustration from wikipedia Sampling Example Aliased Signal 100Hz Sine Wave Sampled at 100Hz Adequately Sampled for Frequency Only (Same # of cycles) 100Hz Sine Wave Sampled at 200Hz Adequately Sampled for Frequency and Shape 100Hz Sine Wave Sampled at 1kHz Hardware Filtering • Filtering – To remove unwanted signals from the signal that you are trying to measure • Analog anti-aliasing low-pass filtering before the A/D converter – To remove all signal frequencies that are higher than the input bandwidth of the device. -

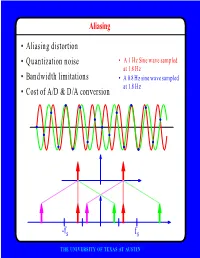

F • Aliasing Distortion • Quantization Noise • Bandwidth Limitations • Cost of A/D & D/A Conversion

Aliasing • Aliasing distortion • Quantization noise • A 1 Hz Sine wave sampled at 1.8 Hz • Bandwidth limitations • A 0.8 Hz sine wave sampled at 1.8 Hz • Cost of A/D & D/A conversion -fs fs THE UNIVERSITY OF TEXAS AT AUSTIN Advantages of Digital Systems Perfect reconstruction of a Better trade-off between signal is possible even after bandwidth and noise severe distortion immunity performance digital analog bandwidth Increase signal-to-noise ratio simply by adding more bits SNR = -7.2 + 6 dB/bit THE UNIVERSITY OF TEXAS AT AUSTIN Advantages of Digital Systems Programmability • Modifiable in the field • Implement multiple standards • Better user interfaces • Tolerance for changes in specifications • Get better use of hardware for low-speed operations • Debugging • User programmability THE UNIVERSITY OF TEXAS AT AUSTIN Disadvantages of Digital Systems Programmability • Speed is too slow for some applications • High average power and peak power consumption RISC (2 Watts) vs. DSP (50 mW) DATA PROG MEMORY MEMORY HARVARD ARCHITECTURE • Aliasing from undersampling • Clipping from quantization Q[v] v v THE UNIVERSITY OF TEXAS AT AUSTIN Analog-to-Digital Conversion 1 --- T h(t) Q[.] xt() yt() ynT() yˆ()nT Anti-Aliasing Sampler Quantizer Filter xt() y(nT) t n y(t) ^y(nT) t n THE UNIVERSITY OF TEXAS AT AUSTIN Resampling Changing the Sampling Rate • Conversion between audio formats Compact 48.0 Digital Disc ---------- Audio Tape 44.1 KHz44.1 48 KHz • Speech compression Speech 1 Speech for on DAT --- Telephone 48 KHz 6 8 KHz • Video format conversion -

Lecture 12: Sampling, Aliasing, and the Discrete Fourier Transform Foundations of Digital Signal Processing

Lecture 12: Sampling, Aliasing, and the Discrete Fourier Transform Foundations of Digital Signal Processing Outline • Review of Sampling • The Nyquist-Shannon Sampling Theorem • Continuous-time Reconstruction / Interpolation • Aliasing and anti-Aliasing • Deriving Transforms from the Fourier Transform • Discrete-time Fourier Transform, Fourier Series, Discrete-time Fourier Series • The Discrete Fourier Transform Foundations of Digital Signal Processing Lecture 12: Sampling, Aliasing, and the Discrete Fourier Transform 1 News Homework #5 . Due this week . Submit via canvas Coding Problem #4 . Due this week . Submit via canvas Foundations of Digital Signal Processing Lecture 12: Sampling, Aliasing, and the Discrete Fourier Transform 2 Exam 1 Grades The class did exceedingly well . Mean: 89.3 . Median: 91.5 Foundations of Digital Signal Processing Lecture 12: Sampling, Aliasing, and the Discrete Fourier Transform 3 Lecture 12: Sampling, Aliasing, and the Discrete Fourier Transform Foundations of Digital Signal Processing Outline • Review of Sampling • The Nyquist-Shannon Sampling Theorem • Continuous-time Reconstruction / Interpolation • Aliasing and anti-Aliasing • Deriving Transforms from the Fourier Transform • Discrete-time Fourier Transform, Fourier Series, Discrete-time Fourier Series • The Discrete Fourier Transform Foundations of Digital Signal Processing Lecture 12: Sampling, Aliasing, and the Discrete Fourier Transform 4 Sampling Discrete-Time Fourier Transform Foundations of Digital Signal Processing Lecture 12: Sampling, Aliasing, -

Multidimensional Sampling Dr

Multidimensional Sampling Dr. Vishal Monga Motivation for the General Case for Sampling We need the more general case to treat three important applications. 1. Human Vision System: the human vision system is a nonlinear, spatially- varying, non-uniformly sampled system. Rods and cones on the retina, which spatially sample are not arranged in rows and columns. a. Hexagonal Sampling: when modeled as a linear shift-invariant system, the human visual system is circularly bandlimited (lowpass in radial frequency). The optimal uniform sampling grid is hexagonal. Optimal means that we need the fewest discrete-time samples to sample the continuous-space analog signal without aliasing. b. Foveated grid: This is based on the fovea in the retina. When you focus on an object, you sample the object at a high resolution, and the resolution falls off away from the point-of-focus. Shown below is a simple example of a foveated grid. The grid is a 4 x 4 uniform sampling with each of the middle four grids subdivided into 4 x 4 grids themselves. The point of focus is at the middle of the grid. We can convert this grid to a uniform grid in several ways. For example, we could start with a rectangular grid and keep the resolution at the point-of-focus. Then, away from the point-of-focus, we can average the pixel values in increasingly larger blocks of samples. This approach allows the use a foveated grid while maintaining compatibility with systems that require rectangular sampling (e.g. image and video compression standards). 2. Television 650 samples /row 362.5 rows /interlace 2 interlaces /frame 30 frames /sec No two samples taken at the same instant of time Can signals be sampled this way without losing information? How can we handle a. -

Sampling & Anti-Aliasing

CS 431/636 Advanced Rendering Techniques Dr. David Breen University Crossings 149 Tuesday 6PM → 8:50PM Presentation 5 5/5/09 Questions from Last Time? Acceleration techniques n Bounding Regions n Acceleration Spatial Data Structures n Regular Grids n Adaptive Grids n Bounding Volume Hierarchies n Dot product problem Slide Credits David Luebke - University of Virginia Kevin Suffern - University of Technology, Sydney, Australia Linge Bai - Drexel Anti-aliasing n Aliasing: signal processing term with very specific meaning n Aliasing: computer graphics term for any unwanted visual artifact based on sampling n Jaggies, drop-outs, etc. n Anti-aliasing: computer graphics term for fixing these unwanted artifacts n We’ll tackle these in order Signal Processing n Raster display: regular sampling of a continuous(?) function n Think about sampling a 1-D function: Signal Processing n Sampling a 1-D function: Signal Processing n Sampling a 1-D function: Signal Processing n Sampling a 1-D function: n What do you notice? Signal Processing n Sampling a 1-D function: what do you notice? n Jagged, not smooth Signal Processing n Sampling a 1-D function: what do you notice? n Jagged, not smooth n Loses information! Signal Processing n Sampling a 1-D function: what do you notice? n Jagged, not smooth n Loses information! n What can we do about these? n Use higher-order reconstruction n Use more samples n How many more samples? The Sampling Theorem n Obviously, the more samples we take the better those samples approximate the original function n The sampling theorem: A continuous bandlimited function can be completely represented by a set of equally spaced samples, if the samples occur at more than twice the frequency of the highest frequency component of the function The Sampling Theorem n In other words, to adequately capture a function with maximum frequency F, we need to sample it at frequency N = 2F. -

Aliasing, Image Sampling and Reconstruction

https://youtu.be/yr3ngmRuGUc Recall: a pixel is a point… Aliasing, Image Sampling • It is NOT a box, disc or teeny wee light and Reconstruction • It has no dimension • It occupies no area • It can have a coordinate • More than a point, it is a SAMPLE Many of the slides are taken from Thomas Funkhouser course slides and the rest from various sources over the web… Image Sampling Imaging devices area sample. • An image is a 2D rectilinear array of samples • In video camera the CCD Quantization due to limited intensity resolution array is an area integral Sampling due to limited spatial and temporal resolution over a pixel. • The eye: photoreceptors Intensity, I Pixels are infinitely small point samples J. Liang, D. R. Williams and D. Miller, "Supernormal vision and high- resolution retinal imaging through adaptive optics," J. Opt. Soc. Am. A 14, 2884- 2892 (1997) 1 Aliasing Good Old Aliasing Reconstruction artefact Sampling and Reconstruction Sampling Reconstruction Slide © Rosalee Nerheim-Wolfe 2 Sources of Error Aliasing (in general) • Intensity quantization • In general: Artifacts due to under-sampling or poor reconstruction Not enough intensity resolution • Specifically, in graphics: Spatial aliasing • Spatial aliasing Temporal aliasing Not enough spatial resolution • Temporal aliasing Not enough temporal resolution Under-sampling Figure 14.17 FvDFH Sampling & Aliasing Spatial Aliasing • Artifacts due to limited spatial resolution • Real world is continuous • The computer world is discrete • Mapping a continuous function to a -

Oversampling with Noise Shaping • Place the Quantizer in a Feedback Loop Xn() Yn() Un() Hz() – Quantizer

Oversampling Converters David Johns and Ken Martin University of Toronto ([email protected]) ([email protected]) University of Toronto slide 1 of 57 © D.A. Johns, K. Martin, 1997 Motivation • Popular approach for medium-to-low speed A/D and D/A applications requiring high resolution Easier Analog • reduced matching tolerances • relaxed anti-aliasing specs • relaxed smoothing filters More Digital Signal Processing • Needs to perform strict anti-aliasing or smoothing filtering • Also removes shaped quantization noise and decimation (or interpolation) University of Toronto slide 2 of 57 © D.A. Johns, K. Martin, 1997 Quantization Noise en() xn() yn() xn() yn() en()= yn()– xn() Quantizer Model • Above model is exact — approx made when assumptions made about en() • Often assume en() is white, uniformily distributed number between ±∆ ⁄ 2 •∆ is difference between two quantization levels University of Toronto slide 3 of 57 © D.A. Johns, K. Martin, 1997 Quantization Noise T ∆ time • White noise assumption reasonable when: — fine quantization levels — signal crosses through many levels between samples — sampling rate not synchronized to signal frequency • Sample lands somewhere in quantization interval leading to random error of ±∆ ⁄ 2 University of Toronto slide 4 of 57 © D.A. Johns, K. Martin, 1997 Quantization Noise • Quantization noise power shown to be ∆2 ⁄ 12 and is independent of sampling frequency • If white, then spectral density of noise, Se()f , is constant. S f e() ∆ 1 Height k = ---------- ---- x f 12 s f f f s 0 s –---- ---- 2 2 University of Toronto slide 5 of 57 © D.A. Johns, K. Martin, 1997 Oversampling Advantage • Oversampling occurs when signal of interest is bandlimited to f0 but we sample higher than 2f0 • Define oversampling-rate OSR = fs ⁄ ()2f0 (1) • After quantizing input signal, pass it through a brickwall digital filter with passband up to f0 y ()n 1 un() Hf() y2()n N-bit quantizer Hf() 1 f f fs –f 0 f s –---- 0 0 ---- 2 2 University of Toronto slide 6 of 57 © D.A. -

Sampling and Quantization

Chapter 5 Sampling and Quantization Often the domain and the range of an original signal x(t) are modeled as contin- uous. That is, the time (or spatial) coordinate t is allowed to take on arbitrary real values (perhaps over some interval) and the value x(t) of the signal itself is allowed to take on arbitrary real values (again perhaps within some interval). As mentioned previously in Chapter XX, such signals are called analog signals. A continuous model is convenient for some situations, but in other situations it is more convenient to work with digital signals — i.e., signals which have a discrete (often finite) domain and range. The process of digitizing the domain is called sampling and the process of digitizing the range is called quantization. Most devices we encounter deal with both analog and digital signals. Digi- tal signals are particularly robust to noise, and extremely efficient and versatile means for processing digital signals have been developed. On the other hand, in certain situations analog signals are sometimes more appropriate or even necessary. For example, most underlying physical processes are analog (or at least most conveniently modeled as analog), including the human sensorimotor systems. Hence, analog signals are typically necessary to interface with sensors and actuators. Also, some types of data processing and transmission are most conveniently performed with analog signals. Thus, the conversion of analog sig- nals to digital signals (and vice versa) is an important part of many information processing systems. In this chapter, we consider some of the fundamental issues and techniques in converting between analog and digital signals.