Aspj/Apjinternational/Aspj F/Index.Asp ASPJ–Afrique Etfrancophonie4

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Coming Turkish- Iranian Competition in Iraq

UNITeD StateS INSTITUTe of Peace www.usip.org SPeCIAL RePoRT 2301 Constitution Ave., NW • Washington, DC 20037 • 202.457.1700 • fax 202.429.6063 ABOUT THE REPO R T Sean Kane This report reviews the growing competition between Turkey and Iran for influence in Iraq as the U.S. troop withdrawal proceeds. In doing so, it finds an alignment of interests between Baghdad, Ankara, and Washington, D.C., in a strong and stable Iraq fueled by increased hydrocarbon production. Where possible, the United States should therefore encourage The Coming Turkish- Turkish and Iraqi cooperation and economic integration as a key part of its post-2011 strategy for Iraq and the region. This analysis is based on the author’s experiences in Iraq and Iranian Competition reviews of Turkish and Iranian press and foreign policy writing. ABOUT THE AUTHO R in Iraq Sean Kane is the senior program officer for Iraq at the United States Institute of Peace (USIP). He assists in managing the Institute’s Iraq program and field mission in Iraq and serves as the Institute’s primary expert on Iraq and U.S. policy in Iraq. Summary He previously worked for the United Nations Assistance Mission • The two rising powers in the Middle East—Turkey and Iran—are neighbors to Iraq, its for Iraq from 2006 to 2009. He has published on the subjects leading trading partners, and rapidly becoming the most influential external actors inside of Iraqi politics and natural resource negotiations. The author the country as the U.S. troop withdrawal proceeds. would like to thank all of those who commented on and provided feedback on the manuscript and is especially grateful • Although there is concern in Washington about bilateral cooperation between Turkey and to Elliot Hen-Tov for generously sharing his expertise on the Iran, their differing visions for the broader Middle East region are particularly evident in topics addressed in the report. -

The Association for Diplomatic Studies and Training Foreign Affairs Oral History Project

The Association for Diplomatic Studies and Training Foreign Affairs Oral History Project PETER KOVACH Interviewed by: Charles Stuart Kennedy Initial Interview Date: April 18, 2012 Copyright 2015 ADST Q: Today is the 18th of April, 2012. Do you know ‘Twas the 18th of April in ‘75’? KOVACH: Hardly a man is now alive that remembers that famous day and year. I grew up in Lexington, Massachusetts. Q: We are talking about the ride of Paul Revere. KOVACH: I am a son of Massachusetts but the first born child of either side of my family born in the United States; and a son of Massachusetts. Q: Today again is 18 April, 2012. This is an interview with Peter Kovach. This is being done on behalf of the Association for Diplomatic Studies and I am Charles Stuart Kennedy. You go by Peter? KOVACH: Peter is fine. Q: Let s start at the beginning. When and where were you born? KOVACH: I was born in Worcester, Massachusetts three days after World War II ended, August the 18th, 1945. Q: Let s talk about on your father s side first. What do you know about the Kovaches? KOVACH: The Kovaches are a typically mixed Hapsburg family; some from Slovakia, some from Hungary, some from Austria, some from Northern Germany and probably some from what is now western Romania. Predominantly Jewish in background though not practice with some Catholic intermarriage and Muslim conversion. Q: Let s take grandfather on the Kovach side. Where did he come from? KOVACH: He was born I think in 1873 or so. -

Vampire Storytellers Handbook (3Rd Edition)

Vampire Storytellers Handbook 1 Vampire Storytellers Handbook By Bruce Baugh, Anne Sullivan Braidwood, Deird’re Brooks, Geoffrey Grabowski, Clayton Oliver and Sven Skoog Table of Contents Introduction............................................................................................................................................................................................4 The Most Important Part... ............................................................................................................................................................6 ...And the Most Important Rule .....................................................................................................................................................6 How to Use This Book...................................................................................................................................................................7 The Game as it is Played..............................................................................................................................................................7 Cool, Not Kewl ..............................................................................................................................................................................9 Violence is Prevalent but Desperate...........................................................................................................................................10 Vampire Music ............................................................................................................................................................................10 -

Al-QAEDA and the ARYAN NATIONS

Al-QAEDA AND THE ARYAN NATIONS A FOUCAULDIAN PERSPECTIVE by HUNTER ROSS DELL Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of The University of Texas at Arlington in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS IN CRIMINOLOGY AND CRIMINAL JUSTICE THE UNIVERSITY OF TEXAS AT ARLINGTON DECEMBER 2006 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS For my parents, Charles and Virginia Dell, without whose patience and loving support, I would not be who or where I am today. November 10, 2006 ii ABSTRACT AL-QAEDA AND THE ARYAN NATIONS A FOUCALTIAN PERSPECTIVE Publication No. ______ Hunter Ross Dell, M.A. The University of Texas at Arlington, 2006 Supervising Professor: Alejandro del Carmen Using Foucauldian qualitative research methods, this study will compare al- Qaeda and the Aryan Nations for similarities while attempting to uncover new insights from preexisting information. Little or no research had been conducted comparing these two organizations. The underlying theory is that these two organizations share similar rhetoric, enemies and goals and that these similarities will have implications in the fields of politics, law enforcement, education, research and United States national security. iii TABLE OF CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS......................................................................................... ii ABSTRACT ................................................................................................................ iii Chapter 1. INTRODUCTION...................................................................................... -

Egypt and the Middle East

Monitoring Study: British Media Portrayals of Egypt Author: Guy Gabriel - AMW adviser Contact details: Tel: 07815 747 729 E-mail: [email protected] Newspapers monitored: All British national daily broadsheets and tabloids, as well as the Evening Standard Monitoring period: May 2008 - May 2009 1 Table of contents: Egypt & the Middle East Regional Importance Israel Camp David Accords The Gulf Sudan Horn of Africa Diplomacy towards Palestine Before Gaza Conflict 2009 Gaza 2009 Diplomacy The Palestine Border Tunnel Economy Crossing Closures Domestic Egypt Food Religion in Society State Ideology Economy Miscellaneous Domestic Threats Emergency Rule & Internal Security Terrorism Egypt & the West Egypt as an Ally 'War on Terror' Suez Ancient Egypt Influence of Egyptian Art Other Legacies Tourism 2 Egypt & the Middle East Regional Importance Various other Middle Eastern countries are sometimes mentioned in connection with Egypt's regional influence, though very rarely those from North Africa. In terms of Egypt's standing in the Middle East as viewed by the US, a meeting in Cairo, as well as Saudi Arabia and Israel, are "necessary step[s] in the careful path Mr Obama is laying out," notes Times chief foreign affairs commentator Bronwen Maddox (29 May 2009). A "solid" Arab-Israeli peace deal "must include President Mubarak of Egypt," says Michael Levy in the same newspaper (14 May 2009). Regarding a divided Lebanon, the Arab League is "tainted by the commitment of the Saudis and Egyptians to one side rather than the other," according to an Independent editorial (13 May 2008). Egypt appointing an ambassador to Iraq generates interest "not only because it is the most populous Arab country but also because its chargé d'affaires in Baghdad was kidnapped and killed in 2005," writes Guardian Middle East editor Ian Black (2 July 2008). -

Bonfield and Engel

THE INSTITUTE FOR MIDDLE EAST STUDIES IMES CAPSTONE PAPER SERIES DIVIDED AND CONQUERED? SHIFTING DYNAMICS AND MECHANISMS OF CONTROL IN TURKISH CIVIL-MILITARY RELATIONS CRAIG E. BONFIELD BRIAN E. ENGEL MAY 2012 THE INSTITUTE FOR MIDDLE EAST STUDIES THE ELLIOTT SCHOOL OF INTERNATIONAL AFFAIRS THE GEORGE WASHINGTON UNIVERSITY © 2012 DIVIDED AND CONQUERED? SHIFTING DYNAMICS AND MECHANISMS OF CONTROL IN TURKISH CIVIL-MILITARY RELATIONS TABLE OF CONTENTS (Click heading to jump to section) ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS 3 METHODOLOGY 4 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY OF FINDINGS 6 A CIVIL-MILITARY THEORETICAL FRAMEWORK 7 Professionalism as an Analytical Conception 8 Differentiating Civilian Control: Objective & Subjective 11 UNPROFESSIONALISM AND SUBJECTIVE CONTROL: THE TURKISH CASE 14 Roots of Subjective Control 1900-1940 15 Challenges to the Order 1940-1960 17 Seeking the Balance 1960-1971 21 Maximizing Control 1970-1980 23 The Zenith of Power 1980-1990 25 Sowing the Seeds of Irony 1990-1999 26 DIVIDING AND CONQUERING THE PASHAS 30 Turkey’s Subjective Evolution 31 Setting the Stage for Conquest 36 Subjective Shifts on the Heels of Copenhagen 40 A House Divided Revealed 43 An E-Compromise 50 The Civil-Military Problematique Reborn 56 DIVERGING PATHS IN ANKARA 58 Democratic Backlash 59 The Enemy of my Enemy & The Threat Within 62 The Dangers of Division 64 Positive Alternatives 66 The Future Path 70 APPENDIX OF FIGURES 72 Figure A – Progression of Relative Political Strength 72 Figure B – Continuum of Turkish Subjective Control 73 INTERVIEWS CONDUCTED 74 WORKS CITED 76 Bonfield & Engel 2 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This project was made possible with the help and support of numerous individuals. First and foremost, we are grateful to Dr. -

The Gospel According to a Personal View Owen O'sullivan OFM Cap

The Gospel according to MARK: a personal view Owen O’Sullivan OFM Cap. 1 © Owen O’Sullivan OFM Cap., 2007. 2 The Gospel according to MARK: a personal view Contents Page Preface iv Sources used v Introduction 1 Main Text 6 3 Preface I was stationed in the Catholic parish of Christ the Redeemer, in Lagmore, West Belfast, Northern Ireland, between 2001 and 2007. When the liturgical year 2005-06 began on the first Sunday of Advent, 27 November 2005, with the Gospel of Mark as the Sunday Gospel, I decided to begin a study of it, in order to learn more about it and understand it better, and, hopefully, to be able to preach better on it at Sunday Mass. I also hoped that this study would be of benefit to me in my faith. It was never on my mind, then or now, that it be published. It is not good enough for that. I have had no formal training in scripture studies, other than what I learned in preparing for the priesthood. Mostly, it has been a matter of what I learned in later years from reflection in daily prayer and personal study, of which I did a good deal. It took me more than a year to complete the study of Mark, but I found that it carried me along, and I wanted to bring it to completion. I was glad to be able to do that early in 2007. The finished product I printed and bound principally for my own use, simply to make it 4 easier to refer to for study or preaching. -

Guide for the War Below/Underground Soldier

Underground Soldier, by Marsha Skrypuch Teacher’s Guide Summary In 1943, in the midst of World War II, Luka is an injured slave labourer in a Nazi work camp. He escapes in a wagon of corpses and tries to walk back home to Kyiv in the hopes of finding his father who had been imprisoned in Siberia by the Soviets (Luka's mother was captured by the Nazis and is a slave labourer at an unknown camp). Instead of walking away from the war, he ends up walking right into the Front. He is saved by the Ukrainian Insurgent Army, a multi-ethnic group of underground freedom fighters who steal weapons from the Nazis and the Soviets and fight both of these brutal regimes. Luka joins and fights with them, but he never loses his desire to find his parents and somehow be reunited with his beloved Lida, who he last saw at the slave labour camp. Underground Soldier is a companion novel to Stolen Child and Making Bombs for Hitler. Historical Background World War II is popularly viewed as the war against Hitler and the Nazis, and while this is largely true from a western perspective, to Ukrainians, Poles, and other Slavs whose homelands were the battleground, the Nazis were not the only enemy. Stalin and the Soviets also committed genocide before and during World War II, and they were responsible for even more deaths than the Nazis. Why are Hitler's crimes common knowledge and Stalin's are not? In part, because Stalin was allied with us during the latter part of WWII. -

Guristas Epic Arc Guide by Jowen Datloran

Guristas Epic Arc Guide by Jowen Datloran Smash and Grab Introduction This is an epic mission arc mission guide that will take you through the various encounters and tasks in the Guristas epic arc level 3 mission chain called “Smash and Grab”. While the guide contains detailed info on encounter opponents and provides hints on trigger spawn mechanics, this was not been my primary goal. Instead I focused on noting down all mission briefings and communications to provide clear insight in the ongoing story. I have included mission debriefings too, when they have contained a little more information than simply a pad on the back for a job well done. Also, in the end of the guide is an “Info on” section where all background info to the various missions is included. This particular epic arc has three starting locations, giving a large span of possible standing requirements to start the arc. The first agent is Arment Caute who is located at the Gallente Counter-intelligence Center in the Orvolle solar system. Before Arment is willing to hand over her first mission of the arc (Enemy of my Enemy) you need to have a minimum of 4.35 in effective standing (skills included) with either the Federal Intelligence Office corporation or the Gallente Federation faction. The second agent is Atma Aulato who is located at the Counter Intelligence Center in the Obe solar system. Before Atma is willing to hand over her first mission of the arc (Turning Coat) you need to have a minimum of 4.35 in effective standing (skills included) with either the Ytiri corporation or the Caldari State faction. -

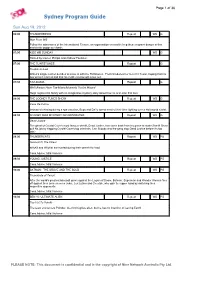

Sydney Program Guide

Page 1 of 36 Sydney Program Guide Sun Aug 19, 2012 06:00 THUNDERBIRDS Repeat WS G Man From Mi5 Follow the adventures of the International Rescue, an organisation created to help those in grave danger in this marionette puppetry classic. 07:00 KIDS WB SUNDAY WS G Hosted by Lauren Phillips and Andrew Faulkner. 07:00 THE FLINTSTONES Repeat G Trouble-In-Law Wilma's single mother decides to move in with the Flintstones. Fred introduces her to a rich Texan, hoping that the two will get married and that his mother-in-law will move out. 07:30 TAZ-MANIA Repeat G We'll Always Have Taz-Mania/Moments You've Missed Hugh regales the family with an imaginative mystery story about how he and Jean first met. 08:00 THE LOONEY TUNES SHOW Repeat WS G Casa De Calma Instead of relaxing during a spa vacation, Bugs and Daffy spend most of their time fighting over a Hollywood starlet. 08:30 SCOOBY DOO MYSTERY INCORPORATED Repeat WS G Dead Justice The ghost of Crystal Cove's most famous sheriff, Dead Justice, has come back from his grave to make Sheriff Stone quit his job by trapping Crystal Cove's top criminals. Can Scooby and the gang stop Dead Justice before it's too late? 09:00 THUNDERCATS Repeat WS PG Survival Of The Fittest WilyKit and WilyKat are hunted during their search for food. Cons.Advice: Mild Violence 09:30 YOUNG JUSTICE Repeat WS PG Cons.Advice: Mild Violence 10:00 BATMAN: THE BRAVE AND THE BOLD Repeat WS PG Triumvirate of Terror! After the world's greatest baseball game against the Legion of Doom, Batman, Superman and Wonder Woman face off against their arch-enemies Joker, Lex Luthor and Cheetah, who gain the upper hand by switching their respective opponents. -

91 Remnants of Empire? British Media Reporting on Zimbabwe Wendy

Remnants of Empire? British media reporting on Zimbabwe Wendy Willems Media and Film Studies Programme School of Oriental and African Studies University of London Keywords: Zimbabwe; British media; foreign news; media coverage; discourse, representation; post-colonial studies Abstract This article explores the various ways in which the British media, and the broadsheets The Guardian and The Daily Telegraph in particular, have framed and represented events in Zimbabwe since 2000. It argues that representations of the situation in Zimbabwe have been largely struggles over meanings and definitions of the ‘crisis’ in the country. The extensive media coverage of Zimbabwe in the British media generated a significant amount of debate and this article demonstrates how the Zimbabwean government drew upon international media representations in order to define the situation in Zimbabwe as a struggle against imperialism. Introduction Mudimbe (1988) examines how in earlier days navigators, traders, travellers, philosophers and anthropologists played an important role in shaping the modern meaning of Africa and of being African. Whereas Mudimbe stresses the crucial role of anthropology in representing Africa and Africans in the nineteenth century, Askew (2002, 1) argues that in the current age it is essentially the media who is doing the job formerly belonging to anthropologists. News accounts shape in decisive ways people’s perceptions of the world. Since early 2000, Zimbabwe has occupied an important place in both broadcast and print media in Britain. Foreign representations of Zimbabwe and British media coverage in particular, have been sharply criticised by the Zimbabwean government. Public debates, both at home and abroad, on the situation in Zimbabwe often were about representations of the crisis. -

The American Militia Phenomenon: a Psychological

THE AMERICAN MILITIA PHENOMENON: A PSYCHOLOGICAL PROFILE OF MILITANT THEOCRACIES ____________ A Thesis Presented to the Faculty of California State University, Chico ____________ In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts in Political Science ____________ by © Theodore C. Allen 2009 Summer 2009 PUBLICATION RIGHTS No portion of this thesis may be reprinted or reproduced in any manner unacceptable to the usual copyright restrictions without the written permission of the author. iii TABLE OF CONTENTS PAGE Publication Rights ...................................................................................................... iii Abstract....................................................................................................................... vi CHAPTER I. Introduction.............................................................................................. 1 II. Literature Review of the Modern Militia Phenomenon ........................... 11 Government Sources .................................................................... 11 Historical and Scholarly Works.................................................... 13 Popular Media .............................................................................. 18 III. The History of the Militia in America...................................................... 23 The Nexus Between Religion and Race ....................................... 28 Jefferson’s Wall of Separation ..................................................... 31 Revolution and the Church..........................................................