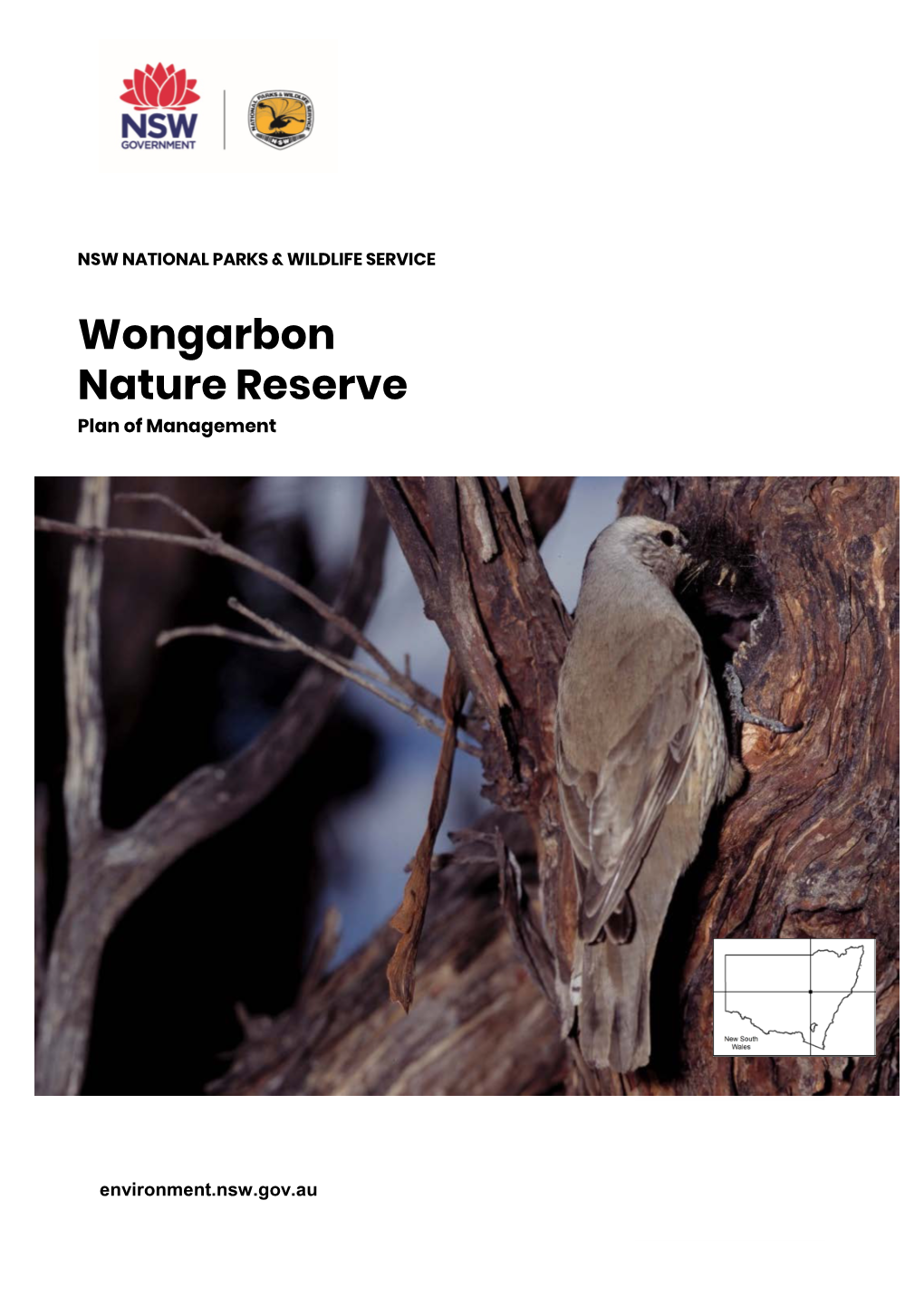

Wongarbon Nature Reserve Plan of Management

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Dubbo Artz Inc. Newsletter

Dubbo Artz inc. Peak volunteer community organisation promoting culture and the arts in the region PO Box 356 Dubbo NSW 2830 ABN: 26 873 857 048 www.dubboartz.org.au President – Di Clifford Newsletter Secretary – Leonie Ward Phone: 6882 0498 Phone or Fax: 6882 6852 Email: [email protected] Mobile: 0409 826 850 Email: [email protected] June July 2014 Media Workshops with Jen Cowley Thank you to all The Office of Sport and Recreation in those who took partnership with Dubbo City Council and the the time to Dubbo Event Network will be delivering two contribute to this edition FREE media workshops. The workshops will be tailored for community/sporting groups and Deadline for event organisers. August/September 2014 2014/2015 Revenue Policy Newsletter Getting your message across: (Fees and Charges) 15 July 2014 An introduction to traditional and social media Community hirers will be pleased to know hopetoun- that DRTCC staff has taken on board [email protected] Monday 21 July - 5.30pm @ the WPCC comments from the community about Fax 6882 6852 Places limited, registration essential: http://dubbo.com.au/events-calendar/get-the- fees and charges of hiring the venue being prohibitive for some community Reproduction of message-an-introduction-to-getting-the-best- material in this groups. The draft 2014/15 Revenue Policy Newsletter is out-of-the-media is currently on public display at Western permitted Plains Cultural Centre and The Macquarie provided the Getting your message across - Tips and Regional Library before it goes to Council source is to be adopted in June. -

Cereal Rust Report 2020 Vol 17 #2

Cereal Rust Report Sydney Institute Plant Breeding Institute of Agriculture Wheat rust situation, July 2020 Cereal Rust Report 2020, Volume 17 Issue 2 22 July 2020 Professor Robert Park The University of Sydney, School of Environmental Sciences, Faculty of Science Email: [email protected] Ph: 02 9351 8806 The first reports of wheat stripe rust and wheat leaf rust during the growing season have been made from New South Wales and South Australia, respectively. Wheat stem rust has not yet been reported. An update is provided on the impact of a new pathotype of the wheat stripe rust pathogen that was first detected in late 2018. Growers in the southern region especially are advised to monitor their cereal crops for rust. Samples of all rusts observed in cereal crops should be submitted for pathotype analysis to the Australian Cereal Rust Survey, details are provided at the end of this document. Wheat stripe rust Five further reports of stripe rust were received over the following week, the southern-most being Lockhart and The first detection of stripe of wheat for 2020 was made on the northern-most being Ghoolendaadi (Table 1). 24th June, from Gollan, near Dubbo, in NSW. Pathotype (pt.; aka race) analysis to date has indicated In the 40 years that stripe rust has been present in eastern the occurrence of pt. 198 E16 A+ J+ T+ 17+ (see below) in Australia, it has managed to survive the summer period and the south. The detection of pt. 64 E0 A- in the north, reappear every year- either in winter or spring, anytime some 670km away, indicates independent survival of the between mid-May to the end of September. -

Western Track Diagrams Version: 3.3 Western Division - Track Diagrams

Western Track Diagrams Manager, Operator and Maintainer of the New South Wales Country Rail Network Disclaimer. This document may not contain the latest infrastructure information. If there is any doubt please refer to the relevant CLNA and current Safe Notices. John Holland Rail Pty Ltd makes no warranties, express or implied, that compliance with the contents of this document shall be sufficient to ensure safe systems of work or operation. It is the document user’s sole responsibility to ensure that the copy of the document it is viewing is the current version of the document as in use by JHR. JHR accepts no liability whatsoever in relation to the use of this document by any party, and JHR excludes any liability which arises in any manner by the use of this document. western File: West Diagram Cover V3.4.cdr Western Division - Track Diagrams Document control Revision Date of Issue Summary of change 3.0 22/2/17 Diagrams generally updated 3.1 18/6/18 Diagrams generally updated 3.3 18/01/2019 Diagrams generally updated 3.5 22/08/2019 Georges Plains and Rydal Loops added The following location have been modified: • Hermidale loop added 3.6 9/04/2020 • Nyngan loop extended • Wongabon loop removed • Stop block added after Warren South Summary of changes from previous version Section Summary of change 9 Wongabon loop removed 17 Nyngan loop extended 18 Hermidale loop added 21 Stop block added after Warren South © JHR UNCONTROLLED WHEN PRINTED Page 1 of 34 Western Track Diagrams Version: 3.3 Western Division - Track Diagrams © JHR UNCONTROLLED -

Community Profile 2018

Australian Early Development Census Community Profile 2018 Dubbo, NSW © 2019 Commonwealth of Australia Since 2002, the Australian Government has worked in partnership with eminent child health research institutes, the Centre for Community Child Health, Royal Children’s Hospital, Melbourne, and the Telethon Kids Institute, Perth to deliver the Australian Early Development Census program to communities. The Australian Government continues to work with its partners, and with state and territory governments to implement the AEDC nationwide. Contents About the Australian Early Development Census .............................. 2 Note on presentation conventions: the hyphen (-) is used throughout the tables in this Community Profile where Australian Early Development Census How to use this AEDC data. ............................................................ 4 data was not collected or not reported for any given year. All percentages presented in this Community Profile have been rounded to one decimal About this community ..................................................................... 5 place. Figures may not add up to 100% due to rounding. Information about children in this community ................................... 6 Note on links: the symbol is used in this document to highlight links to the Australian Early Development Census website: www.aedc.gov.au. AEDC domain results ......................................................................... 9 These links will connect you with further information and resources. AEDC results -

Macquarie River Bird Trail

Bird Watching Trail Guide Acknowledgements RiverSmart Australia Limited would like to thank the following for their assistance in making this trail and publication a reality. Tim and Janis Hosking, and the other members of the Dubbo Field Naturalists and Conservation Society, who assisted with technical information about the various sites, the bird list and with some of the photos. Thanks also to Jim Dutton for providing bird list details for the Burrendong Arboretum. Photographers. Photographs were kindly provided by Brian O’Leary, Neil Zoglauer, Julian Robinson, Lisa Minner, Debbie Love, Tim Hosking, Dione Carter, Dan Giselsson, Tim Ralph and Bill Phillips. This project received financial support from the Australian Bird Environment Foundation of Sacred kingfisher photo: Dan Giselsson BirdLife Australia. Thanks to Warren Shire Council, Sarah Derrett and Ashley Wielinga in particular, for their assistance in relation to the Tiger Bay site. Thanks also to Philippa Lawrence, Sprout Design and Mapping Services Australia. THE MACQuarIE RIVER TraILS First published 2014 The Macquarie valley, in the heart of NSW is one of the The preparation of this guide was coordinated by the not-for-profit organisation Riversmart State’s — and indeed Australia’s — best kept secrets, until now. Australia Ltd. Please consider making a tax deductible donation to our blue bucket fund so we can keep doing our work in the interests of healthy and sustainable rivers. Macquarie River Trails (www.rivertrails.com.au), launched in late 2011, is designed to let you explore the many attractions www.riversmart.org.au and wonders of this rich farming region, one that is blessed See outside back cover for more about our work with a vibrant river, the iconic Maquarie Marshes, friendly people and a laid back lifestyle. -

Western NSW District District Data Profile Murrumbidgee, Far West and Western NSW Contents

Western NSW District District Data Profile Murrumbidgee, Far West and Western NSW Contents Introduction 4 Population – Western NSW 7 Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Population 13 Country of Birth 17 Language Spoken at Home 21 Migration Streams 28 Children & Young People 30 Government Schools 30 Early childhood development 42 Vulnerable children and young people 55 Contact with child protection services 59 Economic Environment 61 Education 61 Employment 65 Income 67 Socio-economic advantage and disadvantage 69 Social Environment 71 Community safety and crime 71 2 Contents Maternal Health 78 Teenage pregnancy 78 Smoking during pregnancy 80 Australian Mothers Index 81 Disability 83 Need for assistance with core activities 83 Households and Social Housing 85 Households 85 Tenure types 87 Housing affordability 89 Social housing 91 3 Contents Introduction This document presents a brief data profile for the Western New South Wales (NSW) district. It contains a series of tables and graphs that show the characteristics of persons, families and communities. It includes demographic, housing, child development, community safety and child protection information. Where possible, we present this information at the local government area (LGA) level. In the Western NSW district there are twenty-two LGAS: • Bathurst Regional • Blayney • Bogan • Bourke • Brewarrina • Cabonne • Cobar • Coonamble • Cowra • Forbes • Gilgandra • Lachlan • Mid-western Regional • Narromine • Oberon • Orange • Parkes • Walgett • Warren • Warrumbungle Shire • Weddin • Western Plains Regional The data presented in this document is from a number of different sources, including: • Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS) • Bureau of Crime Statistics and Research (BOCSAR) • NSW Health Stats • Australian Early Developmental Census (AEDC) • NSW Government administrative data. -

Country Train Notice 0176-2016

Country Train Notice 0176-2016 The Rail Motor Society South Western Branches Tour TO BE READ IN CONJUNCTION WITH TAA 0589-2016 AND STN 0824-2016 Warning: Block Working Conditions may apply. Saturday 11th June 2016 7R01 on Sat 11/06/2016 will run as tabled by Sydney Trains to pass Hermitage 1030, pass Coxs River 1042, Wallerawang 1042, Tarana 1108, Raglan 1138, Kelso 1141, Bathurst 1146, Newbridge 1219, Murrobo 1235, arrive Blayney 1238 depart 1313, pass Polona 1325, Spring Hill 1333, Orange East Fork Jct 1344, arrive Orange 1350 depart 1400, pass Kerrs Creek 1426, arrive Stuart Town 1451 depart 1520, pass Wellington 1550, Combo 1606, arrive Geurie 1613 depart 1638, pass Wongarbon 1649, arrive Dubbo 1710 thence as tabled by ARTC Sunday 12th June 2016 7R03 on Sun 12/06/2016 will run as tabled by ARTC to depart Dubbo 0800, pass Troy Jct 0808, Talbragar 0814, Mogriguy 0826, Eumungerie 0839, Balladoran 0850, Gilgandra AWB 0911, Gilgandra BWS 0914, Gilgandra 0918, Curban 0943, Armatree 1002, Gular 1020, Combara 1050, Coonamble Agrigrain 1109, Coonamble Main Line Grain Load Site 1112, Coonamble 1115 – forms 7R04 7R04 on Sun 12/06/2016 will depart Coonamble 1430, pass Coonamble Main Line Grain Load Site 1433, Coonamble Agrigrain 1436, Combara 1454, Gular 1523, Armatree 1541, Curban 1600, Gilgandra 1625, Gilgandra BWS 1627, Gilgandra AWB 1629, Balladoran 1642, Eumungerie 1652, Mogriguy 1704, Talbragar 1716, Troy Jct 1723, Dubbo 1731 thence as tabled by ARTC Monday 13th June 2016 7R05 on Mon 13/06/2016 will run as tabled by ARTC to depart Narromine -

August 2020 Overview

CROWN LAND REVIEW OPERATIONAL LAND AUGUST 2020 OVERVIEW Overview Introduction of the Crown Land Management Act 2016 (CLM Act) has changed management structures for Crown Land with the introduction of Crown Land Managers to replace Crown Land Trusts. The legislation came into force in from 1 July 2018 and required Dubbo Regional Council (DRC) to review and manage 193 Crown Land reserves. Under the Local Government Act 1993, Council manages land through a classification as either ‘Operational’ for ‘Community.’ DRC has completed an extensive a review of the 193 Crown Land reserves. Operational reserves have been reviewed with the fundamental parameters that have underpinned the proposed reclassifications: 1. Where there appears to be no actual public use of the land and or no ongoing need to consult or involve the community in the continued management of the land. 2. Ongoing management of the land parcel is maintained and upgraded with agreed service levels as a corporate function. 3. The changing needs of the community now, and in the future will, require Council to be responsive and flexible in how its assets are applied to services and facilities. 4. Council is seeking to maximise the use of its land holdings economically but in balance with the community’s environmental and social priorities. 5. To correctly classify Council land that has a pure operational focus and function. The purpose of classification is to identify land that should be kept for use by the general public (community), such as parks, and land which have a pragmatic purpose with defined public access, such as a rubbish depot or sewage treatment plant. -

Inquiry Into Rural and Remote School Education in Australia

HUMAN RIGHTS AND EQUAL OPPORTUNITY COMMISSION INQUIRY INTO RURAL AND REMOTE SCHOOL EDUCATION IN AUSTRALIA Submission prepared by: NSW DEPARTMENT OF EDUCATION AND TRAINING 35 BRIDGE STREET SYDNEY CONTENTS SECTION 1. INTRODUCTION The statutory obligations of the Department of Education and Training. The statewide structure for planning and delivering educational services. SECTION 2. THE AVAILABILITY AND ACCESSIBILITY OF PRIMARY AND SECONDARY SCHOOLING IN NSW Refers to the Commission’s Term of Reference 1. SECTION 3. THE QUALITY OF EDUCATIONAL SERVICES AND TECHNOLOGICAL SUPPORT SERVICES Refers to the Commission’s Term of Reference 2. SECTION 4. EDUCATION OF STUDENTS WITH SPECIAL NEEDS Refers to the Commission’s Term of Reference 3, namely whether the education available to children with disabilities, Indigenous children and children from diverse cultural, religious and linguistic backgrounds complies with their human rights. SECTION 5. EXAMPLES OF PROGRAMS FOR STUDENTS, TEACHERS AND THE COMMUNITY OPERATING IN RURAL AREAS OF NEW SOUTH WALES SECTION 6. REVIEW AND CONCLUSION ATTACHMENTS (not included in this electronic version) Section 1: Introduction 1. Profile of Students and Schools in Rural Districts, 1998 2. Agenda 99 Section 2: The Availability and Accessibility of Primary and Secondary Schooling in NSW 3. Schools Attracting Incentive Benefits 4. Rural Schools in the DSP Program by District Section 3: The Quality of Educational Services and Technological Support Services 5. Access Program 6. Bourke High School 1997 Annual Report 7. Report on the Satellite Trial in Open Line, 14 May 1999 8. Aboriginal Identified Positions in Schools and District Offices in Rural and Remote NSW 9. School Attendance Section 4: Education of Students with Special Needs 10. -

Demonstrating the Potential Resilience of Fox Populations to Coordinated Landholder Baiting Programs for Agricultural Protection

Final Report to the Australian Pest Animal Research Program Demonstrating the potential resilience of fox populations to coordinated landholder baiting programs for agricultural protection Andrew Bengsen New South Wales Department of Primary Industries 30 June 2013 1 of 28 Table of contents Project summary and recommendations ................................................... 3 Acknowledgements ............................................................................ 4 Project information............................................................................ 5 Objectives....................................................................................... 6 Background...................................................................................... 7 Study area....................................................................................... 8 Methods.......................................................................................... 9 Baiting ........................................................................................ 9 Movement and survival of foxes........................................................... 9 Bait exposure ...............................................................................10 Camera trap surveys .......................................................................10 Results ..........................................................................................12 Baiting effort................................................................................12 Fox movements -

Vol 3 Part 9 Historic Heritage

Dubbo Zirconia Project Historic Heritage Assessment Prepared by OzArk Environmental and Heritage Management Pty Ltd August 2013 Specialist Consultant Studies Compendium Volume 3, Part 9 This page has intentionally been left blank Historic Heritage Assessment Prepared for: R.W. Corkery & Co. Pty Limited 62 Hill Street ORANGE NSW 2800 Tel: (02) 6362 5411 Fax: (02) 6361 3622 Email: [email protected] On behalf of: Australian Zirconia Ltd 65 Burswood Road BURSWOOD WA 6100 Tel: (08) 9227 5677 Fax: (08) 9227 8178 Email: [email protected] Prepared by: OzArk Environmental and Heritage Management Pty Ltd 145 Wingewarra Street PO Box 2069 DUBBO NSW 2830 Tel: (02) 6882 0118 Fax: (02) 6882 0630 Email: [email protected] Ref No: 741 August 2013 OzArk Environmental and Heritage Management Pty Ltd AUSTRALIAN ZIRCONIA LIMITED SPECIALIST CONSULTANT STUDIES Dubbo Zirconia Project Part 9: Historic Heritage Assessment Report No. 545/05 This page has been intentionally left blank OzArk Environmental and Heritage Management Pty Ltd Single tree on top of a crest on the ‘Grandale’ property, near Toongi, NSW. HISTORIC HERITAGE ASSESSMENT Dubbo Zirconia Project August 2013 Report Prepared by OzArk Environmental & Heritage Management Pty Ltd for R.W. Corkery on behalf of Australian Zirconia Limited AUSTRALIAN ZIRCONIA LIMITED SPECIALIST CONSULTANT STUDIES Dubbo Zirconia Project Part 9: Historic Heritage Assessment Report No. 545/05 COPYRIGHT © OzArk Environmental & Heritage Management Pty Ltd, 2013; © Australian Zirconia Ltd, 2013. All intellectual property and copyright reserved. Apart from any fair dealing for the purpose of private study, research, criticism or review, as permitted under the Copyright Act, 1968, no part of this report may be reproduced, transmitted, stored in a retrieval system or adapted in any form or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise) without written permission. -

Committed to Quality Brocklehurst, Ballimore, Wongarbon, Elong Elong and Eumungerie

AT A GLANCE WHO: Dubbo City Council WHAT: Dubbo City Council is the local Dubbo City Council government authority for the city of Dubbo including surrounding villages; Committed to Growth, Committed to Quality Brocklehurst, Ballimore, Wongarbon, Elong Elong and Eumungerie. WHERE: NSW 2830 WEBSITE: dubbo.nsw.gov.au the City are overseen by him, including roads, footpaths, water supply, sewerage, storm drainage, solid waste management including recycling, emergency management, and “back- of-house” functions like fleet services, design office, traffic engineering and supervision of subdivision and other works by private developers. Infrastructure is of major importance to a regional centre like Dubbo. With a balance sheet of nearly $2 billion worth of assets to assist with delivering the services the residents of and visitors to Dubbo require, Dubbo City Council is constantly focussed on is a rural centre and people must be the provision of new and upgraded farmers, but only 4% are employed assets to meet the needs not only in agriculture. It is perhaps better of today but of the community in 30 known for being a great regional years time. service centre for at least one third of the land area of NSW and beyond into Council is planning for a population southern Queensland. of 55,000 people in the City within 30 years. This will generate the Stewart McLeod is the city’s requirement for projects that create Director Technical Services. All major the economic output and essential engineering services and projects in infrastructure services to support Business View Australia - March-April 2016 9 .