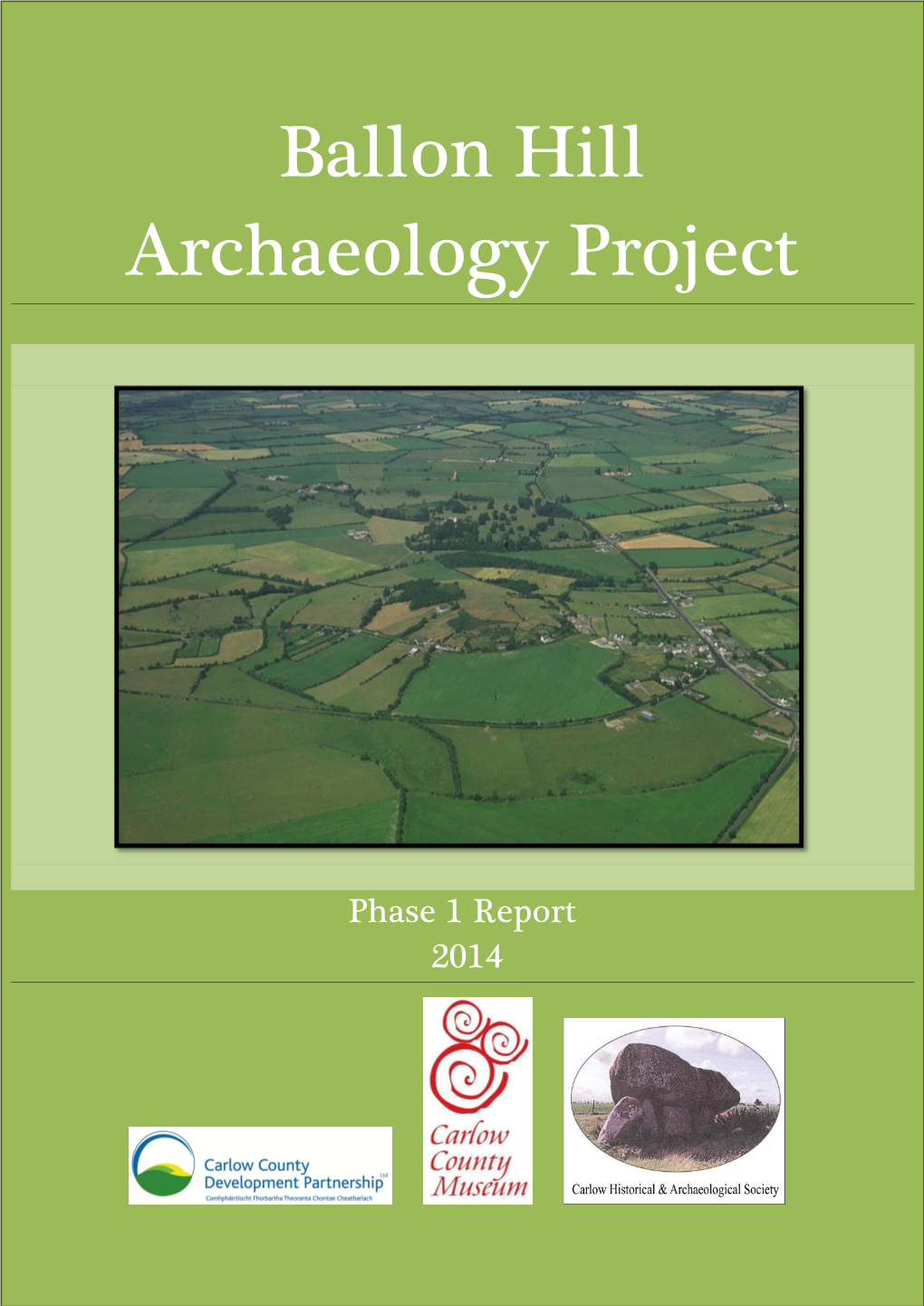

Ballon Hill Archaeology Project Archaeology Project

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

REMOTE SENSING a Bibliography of Cultural Resource Studies

REMOTE SENSING A Bibliography of Cultural Resource Studies Supplement No. 0 REMOTE SENSING Aerial Anthropological Perspectives: A Bibliography of Remote Sensing in Cultural Resource Studies Thomas R. Lyons Robert K. Hitchcock Wirth H. Wills Supplement No. 3 to Remote Sensing: A Handbook for Archeologists and Cultural Resource Managers Series Editor: Thomas R. Lyons Cultural Resources Management National Park Service U.S. Department of the Interior Washington, D.C. 1980 Acknowledgments This bibliography on remote sensing in cultural Numerous individuals have aided us. We es resource studies has been compiled over a period pecially wish to acknowledge the aid of Rosemary of about five years of research at the Remote Sen Ames, Marita Brooks, Galen Brown, Dwight Dra- sing Division, Southwest Cultural Resources Cen ger, James Ebert, George Gumerman, James ter, National Park Service. We have been aided Judge, Stephanie Klausner, Robert Lister, Joan by numerous government agencies in the course Mathien, Stanley Morain and Gretchen Obenauf. of this work, including the Department of the In Douglas Scovill, Chief Anthropologist of the Na terior, National Park Service, the U.S. Geological tional Park Service has also encouraged and sup Survey EROS Program, and the National Aero ported us in the pursuit of new research directions. nautics and Space Administration (NASA). Fi Christina Allen aided immeasurably in the com nancial support has been provided by these pilation of this bibliography, not only in procuring agencies as well as by the National Geographic references (especially those dealing with under Society (Grant No. 1177). The Department of An water remote sensing), but also in proofreading the thropology, University of New Mexico, and the entire manuscript. -

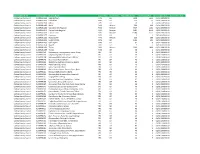

Carlow Scheme Details 2019.Xlsx

Organisation Name Scheme Code Scheme Name Supply Type Source Type Population Served Volume Supplied Scheme Start Date Scheme End Date Carlow County Council 0100PUB1161 Bagenalstown PWS GR 2902 1404 01/01/2009 00:00 Carlow County Council 0100PUB1166 Ballinkillen PWS GR 101 13 01/01/2009 00:00 Carlow County Council 0100PUB1106Bilboa PWS GR 36 8 01/01/2009 00:00 Carlow County Council 0100PUB1162 Borris PWS Mixture 552 146 01/01/2009 00:00 Carlow County Council 0100PUB1134 Carlow Central Regional PWS Mixture 3727 1232 01/01/2009 00:00 Carlow County Council 0100PUB1142 Carlow North Regional PWS Mixture 9783 8659 01/01/2009 00:00 Carlow County Council 0100PUB1001 Carlow Town PWS Mixture 16988 4579 01/01/2009 00:00 Carlow County Council 0100PUB1177Currenree PWS GR 9 2 18/10/2013 00:00 Carlow County Council 0100PUB1123 Hacketstown PWS Mixture 599 355 01/01/2009 00:00 Carlow County Council 0100PUB1101 Leighlinbridge PWS GR 1144 453 01/01/2009 00:00 Carlow County Council 0100PUB1103 Old Leighlin PWS GR 81 9 01/01/2009 00:00 Carlow County Council 0100PUB1178Slyguff PWS GR 9 2 18/10/2013 00:00 Carlow County Council 0100PUB1131 Tullow PWS Mixture 3030 1028 01/01/2009 00:00 Carlow County Council 0100PUB1139Tynock PWS GR 26 4 01/01/2009 00:00 Carlow County Council 0100PRI4063 Ballymurphy Housing estate, Inse-n-Phuca, PRI GR 49 9 01/01/2008 00:00 Carlow County Council 0100PRI4010 Ballymurphy National School PRI GR 49 9 01/01/2008 00:00 Carlow County Council 0100PRI4028 Ballyvergal B&B, Dublin Road, CARLOW PRI GR 49 9 01/01/2008 00:00 Carlow County Council 0100PRI4076 Beechwood Nursing Home. -

2011/B/54 Annual Returns Received Between 11-Nov-2011 and 17-Nov-2011 Index of Submission Types

ISSUE ID: 2011/B/54 ANNUAL RETURNS RECEIVED BETWEEN 11-NOV-2011 AND 17-NOV-2011 INDEX OF SUBMISSION TYPES B1B - REPLACEMENT ANNUAL RETURN B1C - ANNUAL RETURN - GENERAL B1AU - B1 WITH AUDITORS REPORT B1 - ANNUAL RETURN - NO ACCOUNTS CRO GAZETTE, FRIDAY, 18th November 2011 3 ANNUAL RETURNS RECEIVED BETWEEN 11-NOV-2011 AND 17-NOV-2011 Company Company Documen Date Of Company Company Documen Date Of Number Name t Receipt Number Name t Receipt 1246 THE LEOPARDSTOWN CLUB LIMITED B1C 24/10/2011 17811 VITA CORTEX (DUBLIN) LIMITED B1 27/10/2011 1858 MACDLAND LIMITED B1C 12/10/2011 17952 MARS NOMINEES LIMITED B1C 21/10/2011 1995 THOMAS CROSBIE HOLDINGS LIMITED B1C 27/10/2011 18005 THE ST. JOHN OF GOD DEVELOPMENT B1C 28/10/2011 3166 JOHNSON & PERROTT, LIMITED B1C 26/10/2011 COMPANY LIMITED 3446 WATERFORD NEWS & STAR LIMITED B1C 27/10/2011 18099 GERALD STANLEY & SON LIMITED B1C 06/11/2011 3567 DPN NO. 3 B1AU 17/10/2011 18422 MANGAN BROS. HOLDINGS B1AU 20/10/2011 3602 BAILEY GIBSON LIMITED B1C 24/10/2011 18444 DEHYMEATS LIMITED B1C 17/10/2011 3623 ST. LUKE'S HOME, CORK B1C 27/10/2011 18483 COEN STEEL (TULLAMORE) LIMITED B1C 27/10/2011 (INCORPORATED) 18543 BOART LONGYEAR LIMITED B1C 25/10/2011 4091 THE TIPPERARY RACE COMPANY B1C 14/10/2011 18585 LYONS IRISH HOLDINGS LIMITED B1C 11/10/2011 PUBLIC LIMITED COMPANY 18686 BOS (IRELAND) FUNDING LIMITED B1C 20/10/2011 4956 MCMULLAN BROS., LIMITED B1C 18/10/2011 18692 THE KILNACROTT ABBEY TRUST B1C 27/10/2011 6010 VERITAS COMMUNICATIONS B1C 24/10/2011 19441 D. -

Carloviana-No-34-1986 87.Pdf

SPONSORS ARD RI DRY CLEANERS ROYAL HOTEL, CARLOW BURRIN ST. & TULLOW ST., CARLOW. Phone 31935. SPONGING & PRESSING WHILE YOU WAIT, HAND FINISHED SERVICE A PERSONAL HOTEL OF QUALITY Open 8.30 to 6.00 including lunch hour. 4 Hour Service incl. Saturday Laundrette, Kennedy St BRADBURYS· ,~ ENGAGEMENT AND WEDDING RINGS Bakery, Confectionery, Self-Service Restaurant ~e4~{J MADE TO YOUR DESIGN TULLOW STREET, CARLOW . /lf' Large discount on Also: ATHY, PORTLAOISE, NEWBRIDGE, KILKENNY JEWELLERS of Carlow gifts for export CIGAR DIVAN TULLY'S TRAVEL AGENCY NEWSAGENT, CONFECTIONER, TOBACCONIST, etc. DUBLIN ST., CARLOW TULLOW ST., CARLOW. Phone 31257 BRING YOUR FRIENDS TO A MUSICAL EVENING IN CARLOW'S UNIQUE MUSIC LOUNGE EACH GACH RATH AR CARLOVIANA SATURDAY AND SUNDAY. Phone No. 27159 NA BRAITHRE CRIOSTA], CEATHARLACH BUNSCOIL AGUS MEANSCOIL SMYTHS of NEWTOWN SINCE 1815 DEERPARK SERVICE STATION MICHAEL DOYLE TYRE SERVICE & ACCESSORIES BUILDERS PROVIDERS, GENERAL HARDWARE "THE SHAMROCK", 71 TULLOW ST., CARLOW DUBLIN ROAD, CARLOW. PHONE 31414 Phone 31847 THOMAS F. KEHOE Specialist Livestock Auctioneer and Valuer, Farm Sales and Lettings, SEVEN OAKS HOTEL Property and Estate Agent. DINNER DANCES* WEDDING RECEPTIONS* PRIVATE Agent for the Irish Civil Service Building Society. PARTIES * CONFERENCES * LUXURY LOUNGE 57 DUBLIN ST., CARLOW. Telephone 0503/31678, 31963 ATHY RD., CARLOW EILIS Greeting Cards, Stationery, Chocolates, AVONMORE CREAMERIES LTD. Whipped Ice Cream and Fancy Goods GRAIGUECULLEN, CARLOW. Phone 31639 138 TULLOW STREET DUNNY'$ MICHAEL WHITE, M.P.S.I. VETERINARY & DISPENSING CHEMIST BAKERY & CONFECTIONERY PHOTOGRAPHIC & TOILET GOODS CASTLE ST., CARLOW. Phone 31151 39 TULLOW ST., CARLOW. Phone 31229 CARLOW SCHOOL OF MOTORING LTD. A. O'BRIEN (VAL SLATER)* EXPERT TUITION WATCHMAKER & JEWELLER 39 SYCAMORE ROAD. -

Science in Archaeology: a Review Author(S): Patrick E

Science in Archaeology: A Review Author(s): Patrick E. McGovern, Thomas L. Sever, J. Wilson Myers, Eleanor Emlen Myers, Bruce Bevan, Naomi F. Miller, S. Bottema, Hitomi Hongo, Richard H. Meadow, Peter Ian Kuniholm, S. G. E. Bowman, M. N. Leese, R. E. M. Hedges, Frederick R. Matson, Ian C. Freestone, Sarah J. Vaughan, Julian Henderson, Pamela B. Vandiver, Charles S. Tumosa, Curt W. Beck, Patricia Smith, A. M. Child, A. M. Pollard, Ingolf Thuesen, Catherine Sease Source: American Journal of Archaeology, Vol. 99, No. 1 (Jan., 1995), pp. 79-142 Published by: Archaeological Institute of America Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/506880 Accessed: 16/07/2009 14:57 Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use, available at http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp. JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use provides, in part, that unless you have obtained prior permission, you may not download an entire issue of a journal or multiple copies of articles, and you may use content in the JSTOR archive only for your personal, non-commercial use. Please contact the publisher regarding any further use of this work. Publisher contact information may be obtained at http://www.jstor.org/action/showPublisher?publisherCode=aia. Each copy of any part of a JSTOR transmission must contain the same copyright notice that appears on the screen or printed page of such transmission. JSTOR is a not-for-profit organization founded in 1995 to build trusted digital archives for scholarship. We work with the scholarly community to preserve their work and the materials they rely upon, and to build a common research platform that promotes the discovery and use of these resources. -

The Rivers of Borris County Carlow from the Blackstairs to the Barrow

streamscapes | catchments The Rivers of Borris County Carlow From the Blackstairs to the Barrow A COMMUNITY PROJECT 2019 www.streamscapes.ie SAFETY FIRST!!! The ‘StreamScapes’ programme involves a hands-on survey of your local landscape and waterways...safety must always be the underlying concern. If WELCOME to THE DININ & you are undertaking aquatic survey, BORRIS COMMUNITY GROUP remember that all bodies of water are THE RIVERS potentially dangerous places. MOUNTAIN RIVERS... OF BORRIS, County CARLow As part of the Borris Rivers Project, we participated in a StreamScapes-led Field Trip along the Slippery stones and banks, broken glass Dinin River where we learned about the River’s Biodiversity, before returning to the Community and other rubbish, polluted water courses which may host disease, poisonous The key ambitions for Borris as set out by the community in the Borris Hall for further discussion on issues and initiatives in our Catchment, followed by a superb slide plants, barbed wire in riparian zones, fast - Our Vision report include ‘Keep it Special’ and to make it ‘A Good show from Fintan Ryan, and presentation on the Blackstairs Farming Futures Project from Owen moving currents, misjudging the depth of Place to Grow Up and Grow Old’. The Mountain and Dinin Rivers flow Carton. A big part of our engagement with the River involves hearing the stories of the past and water, cold temperatures...all of these are hazards to be minded! through Borris and into the River Barrow at Bún na hAbhann and the determining our vision and aspirations for the future. community recognises the importance of cherishing these local rivers If you and your group are planning a visit to a stream, river, canal, or lake for and the role they can play in achieving those ambitions. -

24Th January, 2021

LEIGHLIN PARISH NEWSLETTER 2 4 T H J A N UA RY 2 0 2 1 3 R D S U N DAY I N ORDINARY T I M E Contact Details: Remember Fr Pat Hennessy You cannot help the poor, by destroying the rich. 059 9721463 You cannot strengthen the weak, by weakening the strong. Deacon Patrick Roche You cannot bring about prosperity by discouraging thrift. 083 1957783 Parish Centre You cannot lift the wage earner by pulling the wage earner down. 059 9722607 You cannot further the brotherhood Email: of man by inciting class hatred. [email protected] You cannot build character and courage by taking Live Webcam away peoples initiative and independence. www.leighlinparish.ie You cannot help people permanently by doing for them what they could, and should, be doing for themselves. Mass Times: Leighlinbridge Webcam No Public Masses To view Webcam log on to www.leighlinparish.ie This will open Mass via webcam the website home page. Scroll sown to see Leighlinbridge and Ballinabranna webcams on right hand side. Click on picture of Sat 7.30pm church and then the red arrow in centre of picture to view. Sunday 11am Open for Private Prayer Please note that during current lockdown Masses are from 12 - 4.30pm Leighlinbridge only. Mass Times via Webcam Mon-Fri 9.30am Monday to Friday 9.30am Open for Private Prayer Vigil Saturday 7.30pm 10.30 - 4.30pm Sunday 11am Ballinabranna Donations to Parish Collections No Public Masses Currently the Office are unable to issue the annual envelopes to Open for Private Prayer parishioners. -

Chapter 15 Town and Village Plans / Rural Nodes

Town and Village Plans / Settlement Boundaries CHAPTER 15 TOWN AND VILLAGE PLANS / RURAL NODES Draft Carlow County Development Plan 2022-2028 345 | P a g e Town and Village Plans / Settlement Boundaries Chapter 15 Town and Village Plans / Rural Nodes 15.0 Introduction Towns, villages and rural nodes throughout strategy objectives to ensure the sustainable the County have a key economic and social development of County Carlow over the Plan function within the settlement hierarchy of period. County Carlow. The settlement strategy seeks to support the sustainable growth of these Landuse zonings, policies and objectives as settlements ensuring growth occurs in a contained in this Chapter should be read in sustainable manner, supporting and conjunction with all other Chapters, policies facilitating local employment opportunities and objectives as applicable throughout this and economic activity while maintaining the Plan. In accordance with Section 10(8) of the unique character and natural assets of these Planning and Development Act 2000 (as areas. amended) it should be noted that there shall be no presumption in law that any land zoned The Settlement Hierarchy for County Carlow is in this development plan (including any outlined hereunder and is contained in variation thereof) shall remain so zoned in any Chapter 2 (Table 2.1). Chapter 2 details the subsequent development plan. strategic aims of the core strategy together with settlement hierarchy policies and core Settlement Settlement Description Settlements Tier Typology 1 Key Town Large population scale urban centre functioning as self – Carlow Town sustaining regional drivers. Strategically located urban center with accessibility and significant influence in a sub- regional context. -

National Museum of Ireland Annual Report 2014

Annual Report 2014 final NATIONAL MUSEUM OF IRELAND ANNUAL REPORT 2014 Annual Report 2014 Final CONTENTS Message from the Chairman of the Board of the National Museum of Ireland ………….. Introduction from the Director of the National Museum of Ireland……………………… Collections Art and Industry…………………………………………………………………………... Irish Antiquities…………………………………………………………………………… Irish Folklife…………………………………………………………………………......... Natural History……………………………………………………………………………. Conservation…………………………………………………………………………........ Registration……………………………………………………………………………….. Exhibitions National Museum of Ireland – County Life………………………………………………. National Museum of Ireland – Archaeology……………………………………………… National Museum of Ireland – Decorative Arts and History…………………………….. Services Education and Outreach…………………………………………………………….......... Marketing and PR……………………………………………………………………........ Photography………………………………………………………………………………. Design…………………………………………………………………………………...... Facilities (Accommodation and Security)………………………………………………… 2 Annual Report 2014 Final Administration Financial Management………………………………………………………………......... Human Resource Management…………………………………………………………… Information Communications Technology (ICT) …………………………………........... Publications by Museum Staff…………………………………………………................. Board of the National Museum of Ireland…………………………………………........... Staff Directory…………………………………………………………………………….. 3 Annual Report 2014 Final MESSAGE FROM THE CHAIRMAN, BOARD OF THE NATIONAL MUSEUM OF IRELAND The year 2014 proved challenging in terms of the National -

Behind the Scenes

©Lonely Planet Publications Pty Ltd 689 Behind the Scenes SEND US YOUR FEEDBACK We love to hear from travellers – your comments keep us on our toes and help make our books better. Our well-travelled team reads every word on what you loved or loathed about this book. Although we cannot reply individually to your submissions, we always guarantee that your feedback goes straight to the appropriate authors, in time for the next edition. Each person who sends us information is thanked in the next edition – the most useful submissions are rewarded with a selection of digital PDF chapters. Visit lonelyplanet.com/contact to submit your updates and suggestions or to ask for help. Our award-winning website also features inspirational travel stories, news and discussions. Note: We may edit, reproduce and incorporate your comments in Lonely Planet products such as guidebooks, websites and digital products, so let us know if you don’t want your comments reproduced or your name acknowledged. For a copy of our privacy policy visit lonelyplanet.com/ privacy. Anthony Sheehy, Mike at the Hunt Museum, OUR READERS Steve Whitfield, Stevie Winder, Ann in Galway, Many thanks to the travellers who used the anonymous farmer who pointed the way to the last edition and wrote to us with help- Knockgraffon Motte and all the truly delightful ful hints, useful advice and interesting people I met on the road who brought sunshine anecdotes: to the wettest of Irish days. Thanks also, as A Andrzej Januszewski, Annelise Bak C Chris always, to Daisy, Tim and Emma. Keegan, Colin Saunderson, Courtney Shucker D Denis O’Sullivan J Jack Clancy, Jacob Catherine Le Nevez Harris, Jane Barrett, Joe O’Brien, John Devitt, Sláinte first and foremost to Julian, and to Joyce Taylor, Juliette Tirard-Collet K Karen all of the locals, fellow travellers and tourism Boss, Katrin Riegelnegg L Laura Teece, Lavin professionals en route for insights, information Graviss, Luc Tétreault M Marguerite Harber, and great craic. -

Finn Connection

James Harold FINN Born: 14 Sep 1885 in Liverpool, England Died: 22 Mar 1941 in Buffalo, Erie, New York Beulah Maude GROBE Born: Jun 1889 in New York Marr: 26 Jun 1915 in Niagra, New York, USA. Died: 1976 Barbara FINN Born: 1886 in Toronto, Ontario, Canada William John FINN Born: 28 Feb 1888 in Toronto, Ontario, Canada Died: 9 Jun 1957 in Buffalo, Erie, New York Ede SCHRADER Margaret Mary FINN Born: 24 Sep 1890 in Ontario, Canada Died: 30 Mar 1970 in Erie County Home, Alden, NY Mary Ellen FINN (Bill) William Monroe CLINE Born: 8 May 1890 in Concord, Cabarrus, North Carolina Died: 18 Sep 1949 in Buffalo, Erie, James H FINN New York Born: 27 Jul 1856 in Bagenalstown, Irish Free State Died: 13 Jan 1897 in Buffalo, Erie, Edward Daniel FINN New York Born: 26 Oct 1890 in Buffalo, Erie, New York Mary Ellen Margaret Died: 5 Jul 1934 in Buffalo, Erie, New York MCDONALD Born: 17 Mar 1865 in Kiledmund, Irish Free State (Lily) Lillian Mae CLINE Marr: 1883 Born: 7 Dec 1900 in Concord, Died: 19 Aug 1936 in Buffalo NY Cabarrus, North Carolina Marr: 7 Feb 1920 in Buffalo, Erie, New York Peter FINN Died: 20 Dec 1989 in Elma, Erie, New York Born: 5 Aug 1858 in Bagenalstown, Irish Free State Died: 9 Mar 1887 in Ballycomack, Ireland Joseph Patrick FINN Born: 10 Dec 1891 in Buffalo, Erie, New York Died: 4 Oct 1966 in Buffalo, Erie, New York Anna Josephine TIMM Born: 24 Aug 1894 in New York, USA Marr: 19 Sep 1912 in Buffalo, Erie, New York Died: 11 Oct 1986 in Buffalo, Erie, New York (Nellie) Mary Helen FINN Born: 21 Aug 1893 in Buffalo, Erie, New York Died: -

A1a13os Mo1je3 A11110 1Eujnor

§Gllt,I IISSI Nlltllf NPIIII eq:101Jeq1eq3.epueas uuewnq3 Jeqqea1s1JI A1a13os Mo1Je3 PIO a11110 1euJnor SPONSORS ROYAL HOTEL - 9-13 DUBLIN STREET SOTHERN AUCTIONEERS LTD A Personal Hotel ofQuality Auctioneers. Valuers, Insurance Brokers, 30 Bedrooms En Suite, choice ofthree Conference Rooms. 37 DUBLIN STREET, CARLOW. Phone: 0503/31218. Fax.0503 43765 Weddings, functions, Dinner Dances, Private Parties. District Office: Irish Nationwide Building Society Food Served ALL Day. Phone: 0503/31621 FLY ONTO ED. HAUGHNEY & SON, LTD O'CONNOR'S GREEN DRAKE INN, BORRIS Fuel Merchant, Authorised Ergas Stockists Lounge and Restaurant - Lunches and Evening Meals POLLERTON ROAD, CARLOW. Phone: 0503/31367 Weddings and Parties catered for. GACH RATH AR CARLOVIANA IRISH PERMANENT PLC. ST. MARY'S ACADEMY 122/3 TULLOW STREET, CARLOW CARLOW Phone:0503/43025,43690 Seamus Walker - Manager Carlow DEERPARK SERVICE STATION FIRST NATIONAL BUILDING SOCIETY MARKET CROSS, CARLOW Tyre Service and Accessories Phone: 0503/42925, 42629 DUBLIN ROAD, CARLOW. Phone: 0503/31414 THOMAS F. KEHOE MULLARKEY INSURANCES Specialist Lifestock Auctioneer and Valuer, Farm Sales and Lettings COURT PLACE, CARLOW Property and Estate Agent Phone: 0503/42295, 42920 Agent for the Irish Civil Service Building Society General Insurance - Life and Pensions - Investment Bonds 57 DUBLIN STREET CARLOW. Telephone: 0503/31378/31963 Jones Business Systems GIFTS GALORE FROM Sales and Service GILLESPIES Photocopiers * Cash Registers * Electronic Weighing Scales KENNEDY AVENUE, CARLOW Car Phones * Fax Machines * Office Furniture* Computer/Software Burrin Street, Carlow. Tel: (0503) 32595 Fax (0503) 43121 Phone: 0503/31647, 42451 CARLOW PRINTING CO. LTD DEVOY'S GARAGE STRAWHALL INDUSTRIAL ESTATE, CARLOW TULLOW ROAD, CARLOW For ALL your Printing Requirements.