Eminent Parliamentarians: the Speaker’S Lectures

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Lobbying and All Party Groups

House of Commons Committee on Standards and Privileges Lobbying and All Party Groups Ninth Report of Session 2005–06 HC 1145 House of Commons Committee on Standards and Privileges Lobbying and All Party Groups Ninth Report of Session 2005–06 Report and Appendix, together with formal minutes Ordered by The House of Commons to be printed 23 May 2006 HC 1145 Published on 25 May 2006 by authority of the House of Commons London: The Stationery Office Limited £0.00 The Committee on Standards and Privileges The Committee on Standards and Privileges is appointed by the House of Commons to oversee the work of the Parliamentary Commissioner for Standards; to examine the arrangements proposed by the Commissioner for the compilation, maintenance and accessibility of the Register of Members’ Interests and any other registers of interest established by the House; to review from time to time the form and content of those registers; to consider any specific complaints made in relation to the registering or declaring of interests referred to it by the Commissioner; to consider any matter relating to the conduct of Members, including specific complaints in relation to alleged breaches in the Code of Conduct which have been drawn to the Committee’s attention by the Commissioner; and to recommend any modifications to the Code of Conduct as may from time to time appear to be necessary. Current membership Rt Hon Sir George Young Bt MP (Conservative, North West Hampshire) (Chairman) Rt Hon Kevin Barron MP (Labour, Rother Valley) Rt Hon David Curry MP (Conservative, Skipton & Ripon) Mr Andrew Dismore MP (Labour, Hendon) Nick Harvey MP (Liberal Democrat, North Devon) Mr Brian Jenkins MP (Labour, Tamworth) Mr Elfyn Llwyd MP (Plaid Cymru, Meirionnydd Nant Conwy) Mr Chris Mullin MP (Labour, Sunderland South) The Hon Nicholas Soames MP (Conservative, Mid Sussex) Dr Alan Whitehead MP (Labour, Southampton Test) Powers The constitution and powers of the Committee are set out in Standing Order No. -

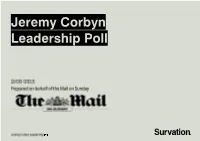

Jeremy Corbyn Leadership Poll Prepared on Behalf of the Mail on Sunday

Jeremy Corbyn Leadership Poll Methodology Jeremy Corbyn Leadership Poll Prepared on behalf of the Mail on Sunday 1. Jeremy Corbyn has just been elected as the new leader of the Labour Party. Of the two options below, who do you think would make the best Prime Minister? Base: All respondents Age Sex Region 2015 Vote Total Midlands & North & Did not 18 - 34 35 - 54 55 + Male Female South CON LAB UKIP LibDem Wales Scotland vote Unweighted total 1033 340 392 301 412 621 403 240 390 264 278 111 79 181 Weighted total 1033 305 360 368 512 520 469 221 343 302 222 99 66 252 Jeremy Corbyn 26.6% 34.0% 24.9% 21.9% 26.6% 26.6% 21.7% 30.2% 31.1% 4.6% 60.1% 18.2% 28.8% 21.7% 275 104 90 81 136 138 102 67 107 14 133 18 19 55 David Cameron 44.2% 29.4% 43.5% 57.0% 51.7% 36.8% 48.4% 44.6% 38.1% 89.4% 11.7% 45.5% 51.5% 24.9% 456 90 156 210 265 191 227 99 130 269 26 45 34 63 Don't know 29.2% 36.6% 31.6% 20.8% 21.6% 36.6% 29.9% 25.2% 30.8% 6.3% 28.3% 36.4% 19.7% 53.4% 302 112 114 77 111 190 140 56 106 19 63 36 13 134 Prepared by Survation on behalf of the Mail on Sunday Survation. Jeremy Corbyn Leadership Poll Prepared on behalf of the Mail on Sunday 2. -

93 Report Oliver Legacy of Roy Jenkins

Reports The legacy of Roy Jenkins Evening meeting, 27 June 2016, with John Campbell and David Steel. Chair: Dick Newby. Report by Douglas Oliver n Monday 27 June, the Liberal ushering in a self-proclaimed ‘permis- founder of the SDP and Liberal Demo- Democrat History Group met sive society’. Jenkins is often seen as one crats – as a giant of post-war politics. Oin Committee Room 4A of of the most important British politicians Campbell looked at the enduring resil- the House of Lords to discuss the legacy never to have become prime minister, ience of Jenkins’ three main themes. of Roy Jenkins. The timing was apt but and this was reflected, also, in the third Campbell shared the platform with for- deeply bittersweet, following as it did in central issue of enduring relevance: Jen- mer Liberal leader, David Steel. the wake of Britain’s decision to leave the kins’ efforts to realign the centre-left and Campbell began with an exploration European Union in its referendum, on centre of British politics. of Jenkins’ legacy as Home Secretary in the longest day of the year, the Thursday The event was chaired by Dick the 1960s, as well as his less celebrated before. The discussion, thirteen years Newby, who worked with the SDP in but fruitful time in the role between 1974 after the death of one of the most impor- the early days after its establishment, and and ’76. Jenkins was, Campbell felt, ‘the tant facilitators of Britain’s European knew Jenkins well, before being elevated right man, in the right job at the right engagement, reflected on how capricious to the House of Lords in September 1997. -

Brexit – Deal Or No Deal? – Reflections from CBS Brexit Breakfast

Brexit – Deal or No Deal? – Reflections from CBS Brexit Breakfast By Beverley Nielsen, Associate Professor at Institute for Design & Economic Acceleration and Senior Fellow at Centre for Brexit Studies The Centre for Brexit Studies ‘Deal or No-Deal’ Brexit Breakfast, hosted 6th September and chaired by Dr Jacob Salder, Research Fellow at Birmingham City Business School, met to consider the impacts on the West Midlands of recent Brexit events with daily curve balls being thrown up for business, institutions and citizens to contend with. Whilst breakfast discussions were held on 6th September, by Monday 9th September (date of writing) the situation had developed with (yet another) cabinet resignation, as Amber Rudd, former Work & Pensions Secretary, dramatically downed tools over the intervening weekend. Whilst listening to Women’s Hour on BBC Radio 4, 9th September, one contributor coined an apt phrase stating that Brexit has ‘burst through the veneer of our society’. The Economist (September 7th-13th), in reviewing the Unconservative Party’s revolution, transforming the world’s oldest political party into ‘radical populists’, commented on the constitutional havoc being wreaked through the longest prorogation of Parliament since 1945 and the whip being withdrawn from 21 Tory MPs — including two former Chancellors, seven former cabinet members and Churchill’s grandson, Sir Nicholas Soames, — one of the ‘biggest political bloodbaths in history’ as The Telegraph put it. John Harris in The Guardian, (9th September) noted, “many Tories seem entirely relaxed about the breakup of the UK, the ultimate sacrifice in their headless pursuit of our divorce from Brussels”. With over 3m EU citizens living in the UK and over 1m British citizens in Europe, many are still very unclear about their future status; many too have commented on the impact of extremism in ‘fanning the flames of hatred’. -

Leadership and Change: Prime Ministers in the Post-War World - Alec Douglas-Home Transcript

Leadership and Change: Prime Ministers in the Post-War World - Alec Douglas-Home Transcript Date: Thursday, 24 May 2007 - 12:00AM PRIME MINISTERS IN THE POST-WAR WORLD: ALEC DOUGLAS-HOME D.R. Thorpe After Andrew Bonar Law's funeral in Westminster Abbey in November 1923, Herbert Asquith observed, 'It is fitting that we should have buried the Unknown Prime Minister by the side of the Unknown Soldier'. Asquith owed Bonar Law no posthumous favours, and intended no ironic compliment, but the remark was a serious under-estimate. In post-war politics Alec Douglas-Home is often seen as the Bonar Law of his times, bracketed with his fellow Scot as an interim figure in the history of Downing Street between longer serving Premiers; in Bonar Law's case, Lloyd George and Stanley Baldwin, in Home's, Harold Macmillan and Harold Wilson. Both Law and Home were certainly 'unexpected' Prime Ministers, but both were also 'under-estimated' and they made lasting beneficial changes to the political system, both on a national and a party level. The unexpectedness of their accessions to the top of the greasy pole, and the brevity of their Premierships (they were the two shortest of the 20th century, Bonar Law's one day short of seven months, Alec Douglas-Home's two days short of a year), are not an accurate indication of their respective significance, even if the precise details of their careers were not always accurately recalled, even by their admirers. The Westminster village is often another world to the general public. Stanley Baldwin was once accosted on a train from Chequers to London, at the height of his fame, by a former school friend. -

One Nation Again

ONE NATION AGAIN ANDREW TYRIE MP THE AUTHOR Andrew Tyrie has been Conservative Member of Parliament for Chichester since May 1997 and was Shadow Paymaster General from 2003 to 2005. He is the author of numerous publications on issues of public policy including Axis of Instability: America, Britain and The New World Order after Iraq (The Foreign Policy Centre and the Bow Group, 2003). The One Nation Group of MPs was founded in 1950. The views expressed in this pamphlet are those of the author and not necessarily of the whole group. One Nation Group, December 2006 Printed by 4 Print, 138 Molesey Avenue, Surrey CONTENTS Acknowledgements 1 One Nation Conservatism 1 2 The History of the Concept 7 3 One Nation Conservatism renewed 15 4 Conclusion 27 Bibliography One Nation members ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to thank the members of the One Nation Group of Conservative MPs whose entertaining and stimulating conversation at our weekly gatherings have brightened many a Westminster evening, particularly during the long years in which the Party appeared to have succumbed to fractious squabbling and representing minority interests. I would also like to thank The Hon Nicholas Soames MP, David Willetts MP and the Rt Hon Sir George Young MP for their comments on an earlier draft; Roger Gough who put together the lion’s share of historical research for this paper; the helpful team in the House of Commons Library; and my ever patient secretaries, Miranda Dewdney-Herbert and Ann Marsh. Andrew Tyrie December 2006 CHAPTER ONE ONE NATION CONSERVATISM The Tory Party, unless it is a national party, is nothing.1 The central tenet of One Nation Conservatism is that the Party must be a national party rather than merely the representative of sectional interests. -

THE 422 Mps WHO BACKED the MOTION Conservative 1. Bim

THE 422 MPs WHO BACKED THE MOTION Conservative 1. Bim Afolami 2. Peter Aldous 3. Edward Argar 4. Victoria Atkins 5. Harriett Baldwin 6. Steve Barclay 7. Henry Bellingham 8. Guto Bebb 9. Richard Benyon 10. Paul Beresford 11. Peter Bottomley 12. Andrew Bowie 13. Karen Bradley 14. Steve Brine 15. James Brokenshire 16. Robert Buckland 17. Alex Burghart 18. Alistair Burt 19. Alun Cairns 20. James Cartlidge 21. Alex Chalk 22. Jo Churchill 23. Greg Clark 24. Colin Clark 25. Ken Clarke 26. James Cleverly 27. Thérèse Coffey 28. Alberto Costa 29. Glyn Davies 30. Jonathan Djanogly 31. Leo Docherty 32. Oliver Dowden 33. David Duguid 34. Alan Duncan 35. Philip Dunne 36. Michael Ellis 37. Tobias Ellwood 38. Mark Field 39. Vicky Ford 40. Kevin Foster 41. Lucy Frazer 42. George Freeman 43. Mike Freer 44. Mark Garnier 45. David Gauke 46. Nick Gibb 47. John Glen 48. Robert Goodwill 49. Michael Gove 50. Luke Graham 51. Richard Graham 52. Bill Grant 53. Helen Grant 54. Damian Green 55. Justine Greening 56. Dominic Grieve 57. Sam Gyimah 58. Kirstene Hair 59. Luke Hall 60. Philip Hammond 61. Stephen Hammond 62. Matt Hancock 63. Richard Harrington 64. Simon Hart 65. Oliver Heald 66. Peter Heaton-Jones 67. Damian Hinds 68. Simon Hoare 69. George Hollingbery 70. Kevin Hollinrake 71. Nigel Huddleston 72. Jeremy Hunt 73. Nick Hurd 74. Alister Jack (Teller) 75. Margot James 76. Sajid Javid 77. Robert Jenrick 78. Jo Johnson 79. Andrew Jones 80. Gillian Keegan 81. Seema Kennedy 82. Stephen Kerr 83. Mark Lancaster 84. -

Catalogue 244: the Churchills 1 15

The Churchills Catalogue 244 July 2021 ABOUT THIS CATALOGUE Most of the books in this catalogue are from the private library of the late The Hon. David Levine AO RFD QC. Most carry his bookplate or book label, usually affixed to the upper pastedown or upper free endpaper. TERMS AND CONDITIONS OF SALE Unless otherwise described, all books are in the original cloth or board binding, and are in very good, or better, condition with defects, if any, fully described. Our prices are nett, and quoted in Australian dollars. Traditional trade terms apply. Items are offered subject to prior sale. All orders will be confirmed by email. PAYMENT OPTIONS We accept the major credit cards, PayPal, and direct deposit to the following account: Account name: Kay Craddock Antiquarian Bookseller Pty Ltd BSB: 083 004 Account number: 87497 8296 Should you wish to pay by cheque we may require the funds to be cleared before items are sent. GUARANTEE As a member or affiliate of the associations listed below, we embrace the time-honoured traditions and courtesies of the book trade. We also uphold the highest standards of business principles and ethics, including your right to privacy. Under no circumstances will we disclose any of your personal information to a third party, unless your specific permission is given. TRADE ASSOCIATIONS Australian and New Zealand Association of Antiquarian Booksellers [ANZAAB] Antiquarian Booksellers’ Association [ABA(Int)] International League of Antiquarian Booksellers [ILAB] Australian Booksellers Association REFERENCES CITED Cohen: Bibliography of the Writings of Sir Winston Churchill. By Ronald Cohen. In three volumes. Thoemmes Continuum, London, 2006. -

THE BRITISH GENERAL ELECTION of 1992 Other Books in This Series

THE BRITISH GENERAL ELECTION OF 1992 Other books in this series THE BRITISH GENERAL ELECTION OF 1945 R. B. McCallum and Alison Readman THE BRITISH GENERAL ELECTION OF 1950 H. G. Nicholas THE BRITISH GENERAL ELECTION OF 1951 David Butler THE BRITISH GENERAL ELECTION OF 1955 David Butler THE BRITISH GENERAL ELECTION OF 1959 David Butler and Richard Rose THE BRITISH GENERAL ELECTION OF 1964 David Butler and Anthony King THE BRITISH GENERAL ELECTION OF 1966 David Butler and Anthony King THE BRITISH GENERAL ELECTION OF 1970 David Butler and Michael Pinto-Duschinsky THE BRITISH GENERAL ELECTION OF FEBRUARY 1974 David Butler and Dennis Kavanagh THE BRITISH GENERAL ELECTION OF OCTOBER 1974 David Butler and Dennis Kavanagh THE 1975 REFERENDUM David Butler and Uwe Kitzinger THE BRITISH GENERAL ELECTION OF 1979 David Butler and Dennis Kavanagh EUROPEAN ELECTIONS AND BRITISH POLITICS David Butler and David Marquand THE BRITISH GENERAL ELECTION OF 1983 David Butler and Dennis Kavanagh PARTY STRATEGIES IN BRITAIN David Butler and Paul Jowett THE BRITISH GENERAL ELECTION OF 1987 David Butler and Dennis Kavanagh The British General Election of 1992 David Butler Fellow ofNuffield College, Oxford Dennis Kavanagh Professor of Politics, University of Nottingham M St. Martin's Press ©David Butler and Dennis Kavanagh 1992 All rights reserved. No reproduction, copy or transmission of this publication may be made without written permission. No paragraph of this publication may be reproduced, copied or transmitted save with written permission or in accordance with the provisions of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988, or under the terms of any licence permitting limited copying issued by the Copyright Licensing Agency, 90 Tottenham Court Road, London WlP 9HE. -

The Collective Responsibility of Ministers, and by Extension, of the Government Side of the Two Houses

RESEARCH PAPER 04/82 The collective 15 NOVEMBER 2004 responsibility of Ministers- an outline of the issues This paper offers an introduction to the convention of collective Cabinet, or ministerial, responsibility and explores in general terms this important constitutional topic. The paper examines both the historical development and the principles and content of collective responsibility. It also covers exemptions from the principle of unanimity such as ‘free votes’ and the ‘agreements to differ’ of 1932, 1975 and 1977. The Paper also examines breaches of the principle of confidentiality, such as ex-ministerial memoirs and the leaking of information to the media. It does not seek to provide a comprehensive analysis of ministerial responsibility or Parliamentary accountability, and should be read as a companion paper to Research Paper 04/31, Individual ministerial responsibility of Ministers- issues and examples This Paper updates and replaces Research Paper 96/55. Oonagh Gay Thomas Powell PARLIAMENT AND CONSTITUTION CENTRE HOUSE OF COMMONS LIBRARY Recent Library Research Papers include: 04/66 The Treaty Establishing a Constitution for Europe: Part I 06.09.04 04/67 Economic Indicators, September 2004 06.09.04 04/68 Children Bill [HL] [Bill 144 of 2003–04] 10.09.04 04/69 Unemployment by Constituency, August 2004 15.09.04 04/70 Income, Wealth & Inequality 15.09.04 04/71 The Defence White Paper 17.09.04 04/72 The Defence White Paper: Future Capabilities 17.09.04 04/73 The Mental Capacity Bill [Bill 120 of 2003-04] 05.10.04 04/74 Social Indicators -

The Rise and Fall of the Labour League of Youth

University of Huddersfield Repository Webb, Michelle The rise and fall of the Labour league of youth Original Citation Webb, Michelle (2007) The rise and fall of the Labour league of youth. Doctoral thesis, University of Huddersfield. This version is available at http://eprints.hud.ac.uk/id/eprint/761/ The University Repository is a digital collection of the research output of the University, available on Open Access. Copyright and Moral Rights for the items on this site are retained by the individual author and/or other copyright owners. Users may access full items free of charge; copies of full text items generally can be reproduced, displayed or performed and given to third parties in any format or medium for personal research or study, educational or not-for-profit purposes without prior permission or charge, provided: • The authors, title and full bibliographic details is credited in any copy; • A hyperlink and/or URL is included for the original metadata page; and • The content is not changed in any way. For more information, including our policy and submission procedure, please contact the Repository Team at: [email protected]. http://eprints.hud.ac.uk/ THE RISE AND FALL OF THE LABOUR LEAGUE OF YOUTH Michelle Webb A thesis submitted to the University of Huddersfield in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy The University of Huddersfield July 2007 The Rise and Fall of the Labour League of Youth Abstract This thesis charts the rise and fall of the Labour Party’s first and most enduring youth organisation, the Labour League of Youth. -

Survey Report

YouGov Survey Results Sample Size: 1096 Labour Party Members Fieldwork: 27th February - 3rd March 2017 EU Ref Vote 2015 Vote Age Gender Social Grade Region Membership Length 2016 Leadership Vote Not Rest of Midlands / Pre Corbyn After Corbyn Jeremy Owen Don't Know / Total Remain Leave Lab 18-39 40-59 60+ Male Female ABC1 C2DE London North Scotland Lab South Wales leader leader Corbyn Smith Did Not Vote Weighted Sample 1096 961 101 859 237 414 393 288 626 470 743 353 238 322 184 294 55 429 667 610 377 110 Unweighted Sample 1096 976 96 896 200 351 434 311 524 572 826 270 157 330 217 326 63 621 475 652 329 115 % % % % % % % % % % % % % % % % % % % % % % Which of the following issues, if any, do you think Labour should prioritise in the future? Please tick up to three. Health 66 67 59 67 60 63 65 71 61 71 68 60 58 67 74 66 66 64 67 70 57 68 Housing 43 42 48 43 43 41 41 49 43 43 41 49 56 45 40 35 22 46 41 46 40 37 Britain leaving the EU 43 44 37 45 39 45 44 41 44 43 47 36 48 39 43 47 37 46 42 35 55 50 The economy 37 37 29 38 31 36 36 37 44 27 39 32 35 40 35 34 40 46 30 29 48 40 Education 25 26 15 26 23 28 26 22 25 26 26 24 22 25 29 23 35 26 25 26 23 28 Welfare benefits 20 19 28 19 25 15 23 23 14 28 16 28 16 21 17 21 31 16 23 23 14 20 The environment 16 17 4 15 21 20 14 13 14 19 15 18 16 21 14 13 18 8 21 20 10 19 Immigration & Asylum 10 8 32 11 10 12 10 9 12 8 10 11 12 6 9 15 6 10 10 8 12 16 Tax 10 10 11 10 8 8 12 8 11 8 8 13 9 11 10 9 8 8 11 13 6 2 Pensions 4 3 7 4 4 3 5 3 4 4 3 6 5 2 6 3 6 2 5 5 3 1 Family life & childcare 3 4 4 4 3 3 3 4 2 5 3 4 1 4 3 5 2 4 3 4 4 3 Transport 3 3 3 3 4 5 2 2 4 1 3 2 3 5 2 2 1 4 3 4 3 0 Crime 2 2 6 2 2 4 2 1 3 2 2 2 1 3 1 3 4 2 2 2 3 1 None of these 0 0 1 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 1 0 0 1 0 0 0 0 0 0 1 Don’t know 1 1 0 1 1 1 0 1 1 0 1 0 1 1 1 0 1 1 0 0 1 1 Now thinking about what Labour promise about Brexit going into the next general election, do you think Labour should..