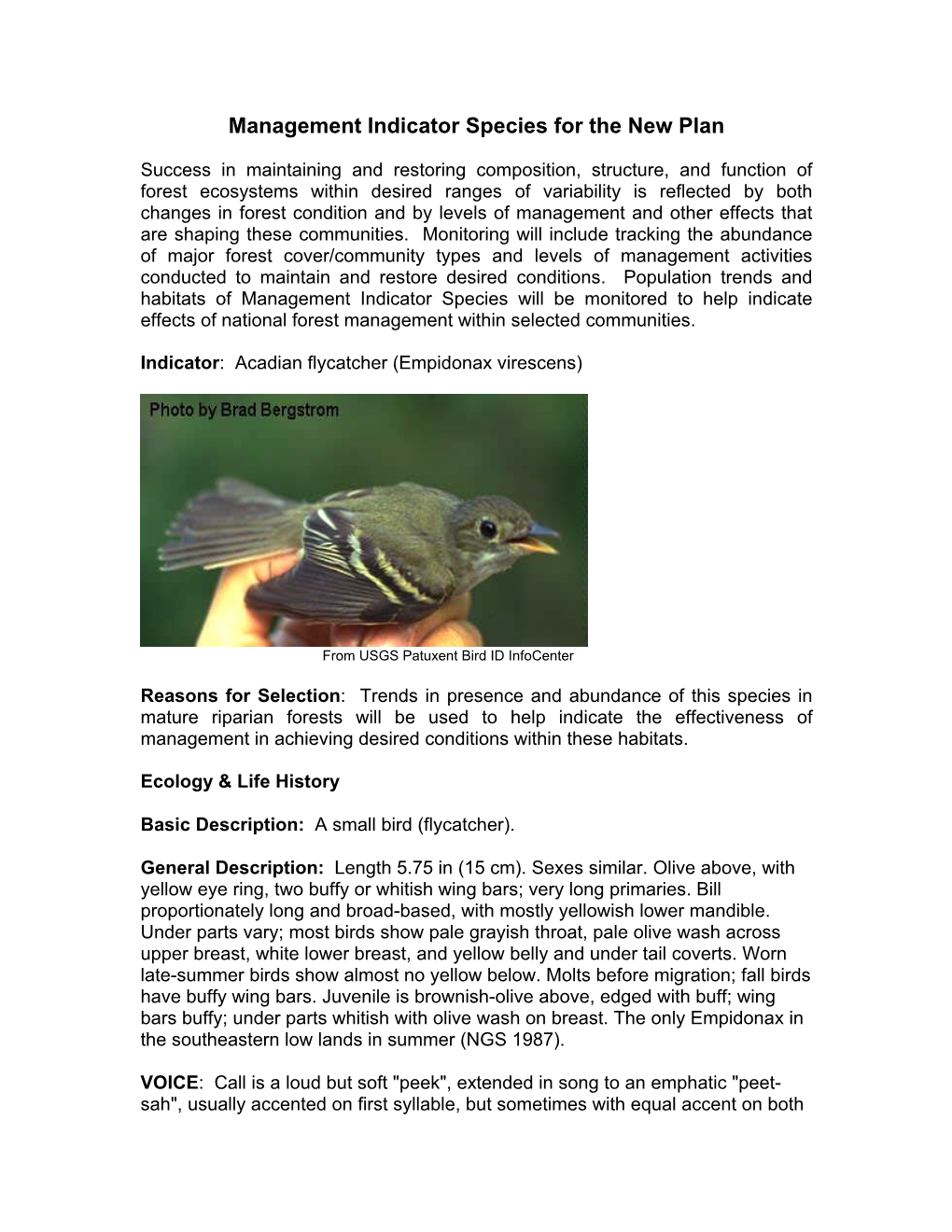

Acadian Flycatcher (Empidonax Virescens)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Journal of the Ontario Field Ornithologists Volume 13 Number 3 December 1995 Ontario Field Ornithologists

The Journal of the Ontario Field Ornithologists Volume 13 Number 3 December 1995 Ontario Field Ornithologists Ontario Field Ornithologists is an organization dedicated to the study of birdlife in Ontario. It was formed to unify the ever-growing numbers of field ornithologists (birders/birdwatchers) across the province and to provide a forum for the exchange of ideas and information among its members. The Ontario Field Ornithologists officially oversees the activities of the Ontario Bird Records Committee (OBRC), publishes a newsletter (OFO News) and a journal (Ontario Birds), hosts field trips throughout Ontario and holds an Annual General Meeting in the autumn. Current President: Jean Iron, 9 Lichen Place, Don Mills, Ontario M3A 1X3 (416) 445-9297 (e-mail: [email protected]). All persons interested in bird study, regardless of their level of expertise, are invited to become members of the Ontario Field Ornithologists. Membership rates can be obtained from the address below. All members receive Ontario Birds and OFO News. Please send membership inquiries to: Ontario Field Ornithologists, Box 62014, Burlington Mall Postal Outlet, Burlington, Ontario L7R 4K2. Ontario Birds Editors: Bill Crins, Ron Pittaway, Ron Tozer Editorial Assistance: Jean Iron, Nancy Checko Art Consultant: Chris Kerrigan Design/Production: Centennial Printers (Peterborough) Ltd. The aim of Ontario Birds is to provide a vehicle for documentation of the birds of Ontario. We encourage the submission of full length articles and short notes on the status, distribution, identification, and behaviour of birds in Ontario, as well as location guides to significant Ontario b!rdwatching areas, book reviews, and similar material of interest on Ontario birds. -

Birds of the East Texas Baptist University Campus with Birds Observed Off-Campus During BIOL3400 Field Course

Birds of the East Texas Baptist University Campus with birds observed off-campus during BIOL3400 Field course Photo Credit: Talton Cooper Species Descriptions and Photos by students of BIOL3400 Edited by Troy A. Ladine Photo Credit: Kenneth Anding Links to Tables, Figures, and Species accounts for birds observed during May-term course or winter bird counts. Figure 1. Location of Environmental Studies Area Table. 1. Number of species and number of days observing birds during the field course from 2005 to 2016 and annual statistics. Table 2. Compilation of species observed during May 2005 - 2016 on campus and off-campus. Table 3. Number of days, by year, species have been observed on the campus of ETBU. Table 4. Number of days, by year, species have been observed during the off-campus trips. Table 5. Number of days, by year, species have been observed during a winter count of birds on the Environmental Studies Area of ETBU. Table 6. Species observed from 1 September to 1 October 2009 on the Environmental Studies Area of ETBU. Alphabetical Listing of Birds with authors of accounts and photographers . A Acadian Flycatcher B Anhinga B Belted Kingfisher Alder Flycatcher Bald Eagle Travis W. Sammons American Bittern Shane Kelehan Bewick's Wren Lynlea Hansen Rusty Collier Black Phoebe American Coot Leslie Fletcher Black-throated Blue Warbler Jordan Bartlett Jovana Nieto Jacob Stone American Crow Baltimore Oriole Black Vulture Zane Gruznina Pete Fitzsimmons Jeremy Alexander Darius Roberts George Plumlee Blair Brown Rachel Hastie Janae Wineland Brent Lewis American Goldfinch Barn Swallow Keely Schlabs Kathleen Santanello Katy Gifford Black-and-white Warbler Matthew Armendarez Jordan Brewer Sheridan A. -

Threat of Climate Change on a Songbird Population Through Its Impacts on Breeding

LETTERS https://doi.org/10.1038/s41558-018-0232-8 Threat of climate change on a songbird population through its impacts on breeding Thomas W. Bonnot 1*, W. Andrew Cox2, Frank R. Thompson3 and Joshua J. Millspaugh4 Understanding global change processes that threaten spe- directly (and indirectly) affects the demographic parameters that cies viability is critical for assessing vulnerability and decid- drive population growth. For example, vulnerability in key species ing on appropriate conservation actions1. Here we combine traits such as physiological tolerances and diets and habitat can lead individual-based2 and metapopulation models to estimate to altered demographics11. For many birds, population persistence is the effects of climate change on annual breeding productivity sensitive to the rates at which young are produced, which can change and population viability up to 2100 of a common forest song- as a function of temperature3,12. In the Midwestern USA, greater bird, the Acadian flycatcher (Empidonax virescens), across the daily temperatures can reduce nest survival and overall productiv- Central Hardwoods ecoregion, a 39.5-million-hectare area of ity for forest-dwelling songbirds3, probably because of increased temperate and broadleaf forests in the USA. Our approach predation from snakes and potentially other predators13–15. Studies integrates local-scale, individual breeding productivity, esti- such as these provide a better mechanistic understanding of how mated from empirically derived demographic parameters climate change may alter the key demographic rates that contribute that vary with landscape and climatic factors (such as forest to population growth, but scaling up to estimate population-level cover, daily temperature)3, into a dynamic-landscape meta- responses requires a quantitative approach that integrates climate population model4 that projects growth of the regional popu- and habitat on a broader scale. -

Designing Suburban Greenways to Provide Habitat for Forest-Breeding Birds

Landscape and Urban Planning 80 (2007) 153–164 Designing suburban greenways to provide habitat for forest-breeding birds Jamie Mason 1, Christopher Moorman ∗, George Hess, Kristen Sinclair 2 Department of Forestry and Environmental Resources, North Carolina State University, Raleigh, NC 27695, USA Received 6 March 2006; received in revised form 25 May 2006; accepted 10 July 2006 Available online 22 August 2006 Abstract Appropriately designed, greenways may provide habitat for neotropical migrants, insectivores, and forest-interior specialist birds that decrease in diversity and abundance as a result of suburban development. We investigated the effects of width of the forested corridor containing a greenway, adjacent land use and cover, and the composition and vegetation structure within the greenway on breeding bird abundance and community composition in suburban greenways in Raleigh and Cary, North Carolina, USA. Using 50 m fixed-radius point counts, we surveyed breeding bird communities for 2 years at 34 study sites, located at the center of 300-m-long greenway segments. Percent coverage of managed area within the greenway, such as trail and other mowed or maintained surfaces, was a predictor for all development- sensitive bird groupings. Abundance and richness of development-sensitive species were lowest in greenway segments containing more managed area. Richness and abundance of development-sensitive species also decreased as percent cover of pavement and bare earth adjacent to greenways increased. Urban adaptors and edge-dwelling birds, such as Mourning Dove, House Wren, House Finch, and European Starling, were most common in greenways less than 100 m wide. Conversely, forest-interior species were not recorded in greenways narrower than 50 m. -

Brown-Headed Cowbird (Molothrus Ater) Doug Powless

Brown-headed Cowbird (Molothrus ater) Doug Powless Grandville, Kent Co., MI. 5/4/2008 © John Van Orman (Click to view a comparison of Atlas I to II) Brown-headed Cowbirds likely flourished Distribution Brown-headed Cowbirds breed in grassland, alongside the Pleistocene megafauna that once prairie, and agricultural habitats across southern roamed North America (Rothstein and Peer Canada to Florida, the Gulf of Mexico, and 2005). In modern times, flocks of cowbirds south into central Mexico (Lowther 1993). The followed the great herds of bison across the center of concentration and highest abundance grasslands of the continent, feeding on insects of the cowbird during summer occurs in the kicked up, and depositing their eggs in other Great Plains and Midwestern prairie states birds’ nests along the way. An obligate brood where herds of wild bison and other ungulates parasite, the Brown-headed Cowbird is once roamed (Lowther 1993, Chace et al. 2005). documented leaving eggs in the nests of hundreds of species (Friedmann and Kiff 1985, Wild bison occurred in southern Michigan and Lowther 1993). The evolution of this breeding across forest openings in the East until about strategy is one of the most fascinating aspects of 1800 before being hunted to near-extinction North American ornithology (Lanyon 1992, across the continent (Baker 1983, Kurta 1995). Winfree 1999, Rothstein et al. 2002), but the Flocks of cowbirds likely also inhabited the cowbird has long drawn disdain. Chapman prairies and woodland openings of southern (1927) called it “. a thoroughly contemptible Michigan prior to the 1800s (Walkinshaw creature, lacking in every moral and maternal 1991). -

Common Name Scientific Name Acadian Flycatcher Empidonax Virescens American Black Duck Anas Rubripes American Coot Fulica Americ

Birds of Seven Islands Wildlife Refuge Common Name Scientific Name Acadian Flycatcher Empidonax virescens American Black Duck Anas rubripes American Coot Fulica americana American Crow Corvus brachyrhynchos American Goldfinch Spinus tristis American Kestrel Falco sparverius American Pipit Athus rubescens American Redstart Setophaga ruticilla American Robin Turdus migratorius American Wigeon Anas americana American Woodcock Scolopax minor Bald Eagle Haliaeetus leucocephalus Baltimore Oriole Icterus galbula Bank Swallow Riparia riparia Barn Owl Tyto alba Barn Swallow Hirundo rustica Barred Owl Strix varia Bay-breasted Warbler Setophaga castanea Belted Kingfisher Megaceryle alcyon Black and White Warbler Mniotilta varia Black Vulture Cathartes atratus Black-Crowned Night Heron Nycticorax nycticorax Blackpoll Warbler Setophaga striata Black-Throated Green Warbler Setophaga virens Blackburnian Warbler Dendroica fusca Blue Grosbeak Passerina caerulea Blue Jay Cyanocitta cristata Blue-Gray Gnatcatcher Polioptila caerulea Blue-headed Vireo Vireo solitarius Blue-winged Teal Anas discors Blue-winged Warbler Vermivora cyanoptera Bobolink Dolichonyx oryzivorus Bonaparte's Gull Chroicoephalus philadephia Broad-winged Hawk Buteo platypterus Brown Creeper Certhia americana Brown Thrasher Toxostoma rufum Brown-Headed Cowbird Molothrus ater Canada Goose Branta canadensis Canada Warbler Carellina canadensis Carolina Chickadee Poecile carolinensis Carolina Wren Thryothorus ludovicianus Cape May Warbler Dendroica tigrina Cedar Waxwing Bombycilla cedrorum -

Learn About Texas Birds Activity Book

Learn about . A Learning and Activity Book Color your own guide to the birds that wing their way across the plains, hills, forests, deserts and mountains of Texas. Text Mark W. Lockwood Conservation Biologist, Natural Resource Program Editorial Direction Georg Zappler Art Director Elena T. Ivy Educational Consultants Juliann Pool Beverly Morrell © 1997 Texas Parks and Wildlife 4200 Smith School Road Austin, Texas 78744 PWD BK P4000-038 10/97 All rights reserved. No part of this work covered by the copyright hereon may be reproduced or used in any form or by any means – graphic, electronic, or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, taping, or information storage and retrieval systems – without written permission of the publisher. Another "Learn about Texas" publication from TEXAS PARKS AND WILDLIFE PRESS ISBN- 1-885696-17-5 Key to the Cover 4 8 1 2 5 9 3 6 7 14 16 10 13 20 19 15 11 12 17 18 19 21 24 23 20 22 26 28 31 25 29 27 30 ©TPWPress 1997 1 Great Kiskadee 16 Blue Jay 2 Carolina Wren 17 Pyrrhuloxia 3 Carolina Chickadee 18 Pyrrhuloxia 4 Altamira Oriole 19 Northern Cardinal 5 Black-capped Vireo 20 Ovenbird 6 Black-capped Vireo 21 Brown Thrasher 7Tufted Titmouse 22 Belted Kingfisher 8 Painted Bunting 23 Belted Kingfisher 9 Indigo Bunting 24 Scissor-tailed Flycatcher 10 Green Jay 25 Wood Thrush 11 Green Kingfisher 26 Ruddy Turnstone 12 Green Kingfisher 27 Long-billed Thrasher 13 Vermillion Flycatcher 28 Killdeer 14 Vermillion Flycatcher 29 Olive Sparrow 15 Blue Jay 30 Olive Sparrow 31 Great Horned Owl =female =male Texas Birds More kinds of birds have been found in Texas than any other state in the United States: just over 600 species. -

Big Oaks National Wildlife Refuge 1661 West JPG Niblo Road Madison, in 47250 812/273 0783 Big Oaks

U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service Big Oaks National Wildlife Refuge 1661 West JPG Niblo Road Madison, IN 47250 812/273 0783 Big Oaks TTY users may reach Big Oaks through National Wildlife Refuge the Federal Information Relay System at 1-800/877 8339 Bird Checklist http:www.fws.gov/midwest/bigoaks U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service 1 1 800/344 WILD www.fws.gov Blue Grosbeak, ©Ron Austing Printed February 2012 “I came to Big Oaks to see the Henslow’s Sparrow and add it to my life list. I knew it was here because Big Oaks is a Globally Important Bird Area, since so many Henslow’s nest here.” Henslow’s Sparrow, ©Ron Austing Welcome to Big Oaks National Wildlife Refuge! Established in 2000, Big Oaks National are listed as a species of special Wildlife Refuge is approximately management concern for the Fish 50,000 acres of diverse habitat. There and Wildlife Service. These included are over 6,000 acres of wetlands, the red-headed woodpecker, northern large blocks of forest habitat and vast flicker, acadian flycatcher, wood grasslands. Each of these unique areas thrush, blue-winged warbler, prairie is ideal habitat for a variety of birds. warbler, cerulean warbler, Kentucky For example, cerulean warblers may be warbler, field sparrow, grasshopper found nesting in the tops of the tallest sparrow, Henslow’s sparrow, eastern trees; Henslow’s sparrows will be seen meadowlark, and orchard oriole. singing in the grasslands and wood Yellow-throated ducks are often spotted paddling in the Hooded Species names and order are in Warbler, Merganser, ©Ron Austing ponded areas of the wetlands. -

Desert Birding in Arizona with a Focus on Urban Birds

Desert Birding in Arizona With a Focus on Urban Birds By Doris Evans Illustrations by Doris Evans and Kim Duffek A Curriculum Guide for Elementary Grades Tucson Audubon Society Urban Biology Program Funded by: Arizona Game & Fish Department Heritage Fund Grant Tucson Water Tucson Audubon Society Desert Birding in Arizona With a Focus on Urban Birds By Doris Evans Illustrations by Doris Evans and Kim Duffek A Curriculum Guide for Elementary Grades Tucson Audubon Society Urban Biology Program Funded by: Arizona Game & Fish Department Heritage Fund Grant Tucson Water Tucson Audubon Society Tucson Audubon Society Urban Biology Education Program Urban Birding is the third of several projected curriculum guides in Tucson Audubon Society’s Urban Biology Education Program. The goal of the program is to provide educators with information and curriculum tools for teaching biological and ecological concepts to their students through the studies of the wildlife that share their urban neighborhoods and schoolyards. This project was funded by an Arizona Game and Fish Department Heritage Fund Grant, Tucson Water, and Tucson Audubon Society. Copyright 2001 All rights reserved Tucson Audubon Society Arizona Game and Fish Department 300 East University Boulevard, Suite 120 2221 West Greenway Road Tucson, Arizona 85705-7849 Phoenix, Arizona 85023 Urban Birding Curriculum Guide Page Table of Contents Acknowledgements i Preface ii Section An Introduction to the Lessons One Why study birds? 1 Overview of the lessons and sections Lesson What’s That Bird? 3 One -

Acadian Flycatcher Empidonax Virescens ILLINOIS RANGE

Acadian flycatcher Empidonax virescens Kingdom: Animalia FEATURES Phylum: Chordata The Acadian flycatcher is a small bird (five and one- Class: Aves half inches) with a relatively large head. Its bill is Order: Passeriformes flattened and broad with tiny bristles at the end. The legs are very short. This flycatcher may be Family: Tyrannidae recognized by its light eye ring and two, white wing ILLINOIS STATUS bars. The body feathers are green with yellow tinting on the sides. Both sexes are similar in appearance. common, native BEHAVIORS ILLINOIS RANGE The Acadian flycatcher is a common migrant and summer resident in bottomland forests, ravines, swampy woods and upland forests of central and southern Illinois. It may be seen in more northern locations in the state but not as frequently. This bird winters from Nicaragua to northern South America. Arriving in Illinois in late April or May, it nests along shaded waterways. The nest is placed about eight to 20 feet above the ground on a low branch of a large tree. The nest looks like a pile of weeds that could have been left in the tree by a flood. Plant stems, fibers and catkins are used by the female Acadian flycatcher to build the nest that is lined with plant materials and spider webs. Two to five white eggs with brown spots are laid. Nests are often parasitized by the brown-headed cowbird that deposits an egg that the Acadian flycatcher will hatch and raise, taking food and care away from its own young. Incubation takes 13 or 14 days and is done solely by the female. -

Greater Rondeau

Greater Rondeau Important Bird Area Conservation Plan Written for the Greater Rondeau IBA Stakeholders by Edward D. Cheskey and William G. Wilson August 2001 A bird’s eye view of the Rondeau peninsula, Rondeau Bay and Lake Erie, Rondeau Important Bird Area Photograph by Austin Wright Table of Contents Acknowledgments ....................................................................................................................................................... 4 1.0 Introduction ........................................................................................................................................................... 5 2.0 The Important Bird Areas Program ....................................................................................................................... 7 3.0 IBA Site Information ............................................................................................................................................. 8 3.1 Location and Description.................................................................................................................................. 8 4.0 IBA Species Information ..................................................................................................................................... 10 4.1 Threatened Species ......................................................................................................................................... 12 4.1.1 The Songbirds ........................................................................................................................................ -

Panama's Canopy Tower and El Valle's Canopy Lodge

FIELD REPORT – Panama’s Canopy Tower and El Valle’s Canopy Lodge January 4-16, 2019 Orange-bellied Trogon © Ruthie Stearns Blue Cotinga © Dave Taliaferro Geoffroy’s Tamarin © Don Pendleton Ocellated Antbird © Carlos Bethancourt White-tipped Sicklebill © Jeri Langham Prepared by Jeri M. Langham VICTOR EMANUEL NATURE TOURS, INC. 2525 WALLINGWOOD DR., AUSTIN, TX 78746 Phone: 512-328-5221 or 800-328-8368 / Fax: 512-328-2919 [email protected] / www.ventbird.com Myriads of magazine articles have touted Panama’s incredible Canopy Tower, a former U.S. military radar tower transformed by Raúl Arias de Para when the U.S. relinquished control of the Panama Canal Zone. It sits atop 900-foot Semaphore Hill overlooking Soberania National Park. While its rooms are rather spartan, the food is Panama’s Canopy Tower © Ruthie Stearns excellent and the opportunity to view birds at dawn from the 360º rooftop Observation Deck above the treetops is outstanding. Twenty minutes away is the start of the famous Pipeline Road, possibly one of the best birding roads in Central and South America. From our base, daily birding outings are made to various locations in Central Panama, which vary from the primary forest around the tower, to huge mudflats near Panama City and, finally, to cool Cerro Azul and Cerro Jefe forest. An enticing example of what awaits visitors to this marvelous birding paradise can be found in excerpts taken from the Journal I write during every tour and later e- mail to participants. These are taken from my 17-page, January 2019 Journal. On our first day at Canopy Tower, with 5 of the 8 participants having arrived, we were touring the Observation Deck on top of Canopy Tower when Ruthie looked up and called my attention to a bird flying in our direction...it was a Black Hawk-Eagle! I called down to others on the floor below and we watched it disappear into the distant clouds.