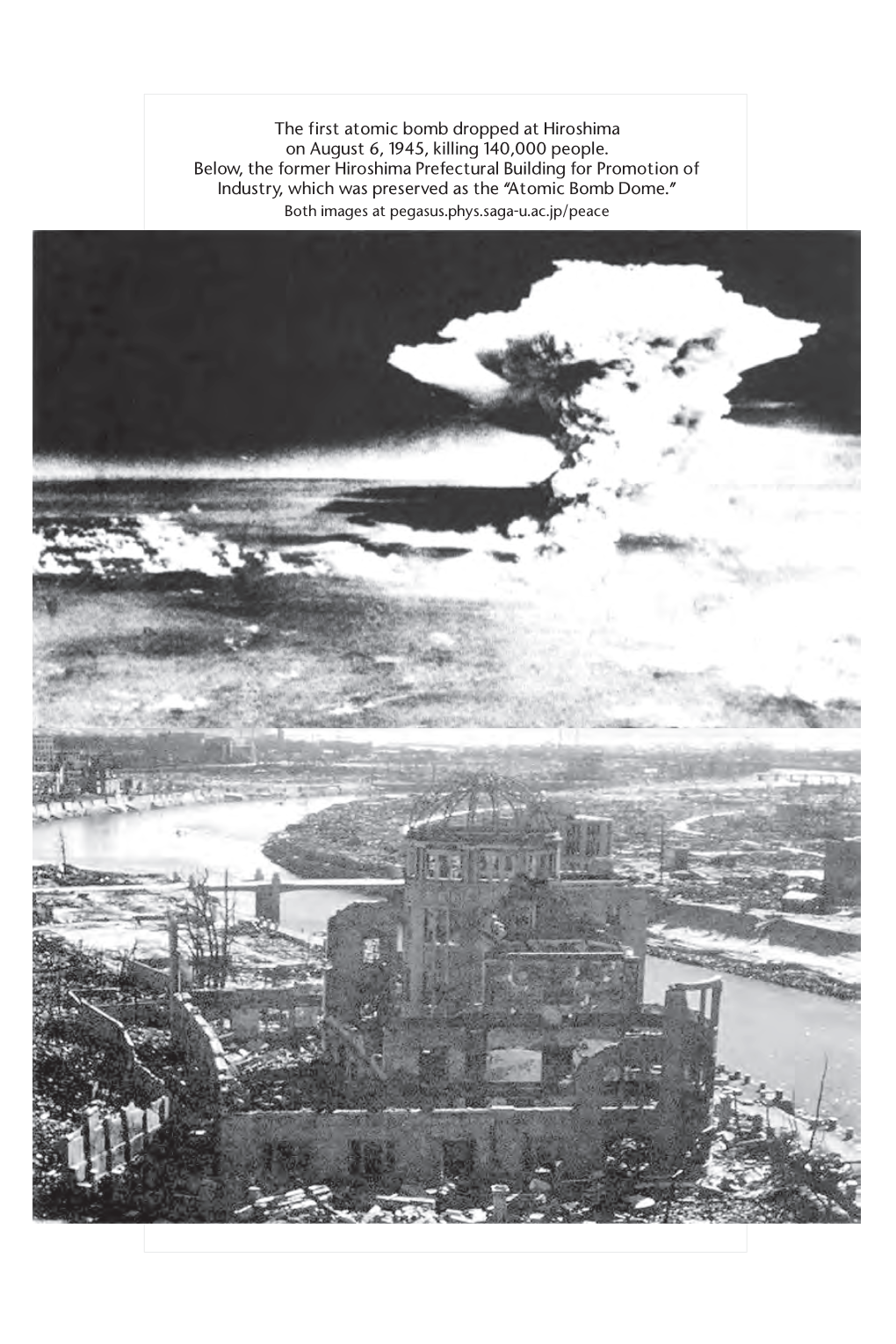

Why Does a Pediatrician Worry About Nuclear Weapons? 153 ------(Dur James N

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Where You Can Discover Content from Different Regions of Japan

Where you can discover content from different regions of Japan Asia TV Forum & Market 2016 Contents 02 “REGIONS OF JAPAN” ‒ Who we are 16 Kyushu Asahi Broadcasting Co., Ltd. 03 Sapporo: City of Films 17 Fukuoka Broadcasting System corporation 04 Hokkaido Broadcasting Co.,Ltd. 18 Saga: A countryside of JAPAN 05 The Sapporo Television Broadcasting Co.,Ltd. 19 69'ners FILM 06 Hello Earth Inc. 20 Okinawa: Tropical Side of Japan 07 Niigata: Welcome to the Snow Country 21 Contact List 08 Niigata Sogo Television Co.,Ltd. 09 Television Niigata Network Co., Ltd. Sapporo 10 Niigata Television Network 21,Inc 11 Kyoto:‘OMOTENASHI’ is a word for KYOTO. Niigata 12 Kyoto Broadcasting System Co., Ltd. Kyoto 13 Mainichi Broadcasting System, Inc. Fukuoka Saga 14 Jupiter Telecommunications Co., Ltd. 15 Fukuoka: Compact and livable city, Fukuoka Okinawa The icons represent following genres Tra Travel Var Variety Food Food Kids Kids Edu Education Doc Documentary Dra Drama Ani Animation Film Film Clu Culture Sce Scenery Other Other Genre 01 “REGIONS OF JAPAN” ‒ Who we are The“REGIONS OF JAPAN” booth is organized by Screen Authority Sapporo (SAS) ; the official film commission to Sapporo City, Hokkaido. We are a showcase from which you can discover the charms from various regions of Japan. Each region has its own distinctive history, lifestyle and cuisine. We bring together 18 companies from 6 regions; Sapporo, Niigata, Kyoto, Fukuoka, Saga and Okinawa. The special feature of our booth is the diversity of regions and the cooperative work between public and private sectors. Not only will you find TV programs, films and animations, but you will also meet future co-productions partners and gateways to local governing bodies. -

Rail Pass Guide Book(English)

JR KYUSHU RAIL PASS Sanyo-San’in-Northern Kyushu Pass JR KYUSHU TRAINS Details of trains Saga 佐賀県 Fukuoka 福岡県 u Rail Pass Holder B u Rail Pass Holder B Types and Prices Type and Price 7-day Pass: (Purchasing within Japan : ¥25,000) yush enef yush enef ¥23,000 Town of History and Hot Springs! JR K its Hokkaido Town of Gourmet cuisine and JR K its *Children between 6-11 will be charged half price. Where is "KYUSHU"? All Kyushu Area Northern Kyushu Area Southern Kyushu Area FUTABA shopping! JR Hakata City Validity Price Validity Price Validity Price International tourists who, in accordance with Japanese law, are deemed to be visiting on a Temporary Visitor 36+3 (Sanjyu-Roku plus San) Purchasing Prerequisite visa may purchase the pass. 3-day Pass ¥ 16,000 3-day Pass ¥ 9,500 3-day Pass ¥ 8,000 5-day Pass Accessible Areas The latest sightseeing train that started up in 2020! ¥ 18,500 JAPAN 5-day Pass *Children between 6-11 will be charged half price. This train takes you to 7 prefectures in Kyushu along ute Map Shimonoseki 7-day Pass ¥ 11,000 *Children under the age of 5 are free. However, when using a reserved seat, Ro ¥ 20,000 children under five will require a Children's JR Kyushu Rail Pass or ticket. 5 different routes for each day of the week. hu Wakamatsu us Mojiko y Kyoto Tokyo Hiroshima * All seats are Green Car seats (advance reservation required) K With many benefits at each International tourists who, in accordance with Japanese law, are deemed to be visiting on a Temporary Visitor R Kyushu Purchasing Prerequisite * You can board with the JR Kyushu Rail Pass Gift of tabi socks for customers J ⑩ Kokura Osaka shops of JR Hakata city visa may purchase the pass. -

By Municipality) (As of March 31, 2020)

The fiber optic broadband service coverage rate in Japan as of March 2020 (by municipality) (As of March 31, 2020) Municipal Coverage rate of fiber optic Prefecture Municipality broadband service code for households (%) 11011 Hokkaido Chuo Ward, Sapporo City 100.00 11029 Hokkaido Kita Ward, Sapporo City 100.00 11037 Hokkaido Higashi Ward, Sapporo City 100.00 11045 Hokkaido Shiraishi Ward, Sapporo City 100.00 11053 Hokkaido Toyohira Ward, Sapporo City 100.00 11061 Hokkaido Minami Ward, Sapporo City 99.94 11070 Hokkaido Nishi Ward, Sapporo City 100.00 11088 Hokkaido Atsubetsu Ward, Sapporo City 100.00 11096 Hokkaido Teine Ward, Sapporo City 100.00 11100 Hokkaido Kiyota Ward, Sapporo City 100.00 12025 Hokkaido Hakodate City 99.62 12033 Hokkaido Otaru City 100.00 12041 Hokkaido Asahikawa City 99.96 12050 Hokkaido Muroran City 100.00 12068 Hokkaido Kushiro City 99.31 12076 Hokkaido Obihiro City 99.47 12084 Hokkaido Kitami City 98.84 12092 Hokkaido Yubari City 90.24 12106 Hokkaido Iwamizawa City 93.24 12114 Hokkaido Abashiri City 97.29 12122 Hokkaido Rumoi City 97.57 12131 Hokkaido Tomakomai City 100.00 12149 Hokkaido Wakkanai City 99.99 12157 Hokkaido Bibai City 97.86 12165 Hokkaido Ashibetsu City 91.41 12173 Hokkaido Ebetsu City 100.00 12181 Hokkaido Akabira City 97.97 12190 Hokkaido Monbetsu City 94.60 12203 Hokkaido Shibetsu City 90.22 12211 Hokkaido Nayoro City 95.76 12220 Hokkaido Mikasa City 97.08 12238 Hokkaido Nemuro City 100.00 12246 Hokkaido Chitose City 99.32 12254 Hokkaido Takikawa City 100.00 12262 Hokkaido Sunagawa City 99.13 -

After the 2011 Tohoku Earthquake, Thirteen Thousand Hectares of Farmlands Were Damaged by Massive Tsunami Near Coastal Sites in Miyagi, Japan

SOIL Discuss., doi:10.5194/soil-2016-12, 2016 Manuscript under review for journal SOIL Published: 18 March 2016 c Author(s) 2016. CC-BY 3.0 License. INVESTIGATION OF ROOTZONE SALINITY WITH FIELD MONITORING SYSTEM AT TSUNAMI AFFECTED RICE FEILDS IN MIYAGI, JAPAN Ieyasu Tokumoto*1, Katsumi Chiba2, Masaru Mizoguchi3, and Hideki Miyamoto1 1Department of Environmental Sciences, Saga University, Saga, Japan 5 2Department of Environmental Sciences, Miyagi University, Sendai, Japan 3Department of Global Agricultural Sciences, University of Tokyo, Tokyo, Japan Correspondence to: Ieyasu Tokumoto ([email protected]) ABSTRACT 10 After the 2011 Tohoku earthquake, thirteen thousand hectares of farmlands were damaged by massive Tsunami near coastal sites in Miyagi, Japan. Some eighty percent of the damaged farmlands have been recovered in 2014, but subsidence and high salinity groundwater make it difficult to completely remove salinity from the soil. To solve the problem, management of saltwater intrusion plays an important role in 15 rootzone salinity control with the Field Monitoring System (FMS), which is remote sensing technology of wireless real-time soil data through the internet data sever to investigate high soil moisture and high salinity in tsunami affected fields. Using the FMS with the time domain transmission system, we monitored soil moisture, electrical conductivity (EC), groundwater level, and EC of groundwater at tsunami damaged 20 paddy fields. The field measurements of the FMS were conducted at two sites of tsunami damaged farmlands in Iwanuma and Higashimatsushima of Miyagi prefecture, Japan. After the Tohoku disaster, co-seismic subsidence of 17-21 cm and 50-60 cm of the land was reported at the sites, respectively. -

2013 TOMODACHI-Mitsui & Co. Leadership Program

2013 TOMODACHI-Mitsui & Co. Leadership Program Executive Summary The TOMODACHI Initiative sincerely thanks Mitsui & Co., Ltd. for the opportunity to develop an innovative U.S.-Japan leadership program that inspires, motivates, and engages a diverse set of young professional leaders in the U.S.-Japan relationship. This program set out to recruit participants for whom this could potentially be a transformative experience. We sought out young professionals from areas across the United States and Japan and fields that did not necessarily have strong U.S.- Japan exchange opportunities. We focused on young professionals (under 35, generally), with various level of experience with U.S.-Japan relations, each selected for their leadership potential and their passion to learn more about the relationship. We recruited both men and women, and we set an additional challenge of strong English language skills for the Japanese participants. This may have been very ambitious criteria, but we were thrilled by the quality and energy of both delegations. We have been impressed by the impact we’ve already seen for many of the participants. We look forward to building on Year One of the program over the next two years to continue to improve the program, and to build a network of young leaders across our two countries. Program Overview The TOMODACHI-Mitsui & Co. Leadership Program is designed to inspire and motivate the next generation of young American and Japanese leaders to be active in U.S.-Japan relations. This bicultural experience provides outstanding young professionals with unique access to leaders and counterparts in the U.S.-Japan arena, along with the opportunity to broaden their perspectives in ways 1 that could enhance their work or support initiatives in their professional fields. -

Monthly Glocal News MAY 2019 ’ Local Partnership Cooperation Division Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Japan

Monthly Glocal News MAY 2019 ’ Local Partnership Cooperation Division Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Japan Saga Prefecture PR event "THE SIGHTS, SOUNDS AND TASTES OF SAGA" From the Seminar in the Philippines Learn more about the regions participated in our Re- gional Promotion Seminar on December 5, 2018 53 Stations of the Tokaido Road Shizuoka Prefecture okaido has been a main artery of appointment as Saga-Japan International Tasting of Saga’s sake Goodwill Ambassadors Japan since the olden days. In the Edo period, Tokaido linked On February 8, "THE SIGHTS, SOUNDS AND TASTES OF SAGA" was held at the Edo, the center of political pow- residence of Japanese Ambassador in Philippines in cooperation with the governor of T er under the Shogunate, and Kyoto, the Saga Prefecture. Through promoting filming locations, Saga Prefecture has attracted formal capital. Pictures of ‘‘the 53 Sta- Philippine tourists. In this event, Secretary of Finance Carlos G. Dominguez III and his tions of the Tokaido’’ drawn by Utagaw spouse, Mrs. Cynthia A. Dominguez were appointed to Saga-Japan International Good- Hiroshige describe scenes of each post will Ambassadors. Saga Prefecture hopes to further deepen relationships with the Philip- town along the ancient Tokaido. 22 of pine people. these, almost half of them, are preserved in Shizuoka. Diplomats' Study Tour to Iizuka City, Fukuoka Prefecture Since the start of operation of Tokaido Shinkansen (bullet train) between Tokyo and Shin-Osaka in 1964, Tokaido has played more important role in Japan’s travel and transportation. Courtesy visit to Mr. Makoto Katamine, With the students of course specialized in Mayor of Iizuka City cake-making, Iizuka High shool The Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Japan and Iizuka City held a Diplomats' Study Tour to Iizuka City for the diplomatic corps in Japan from April 22 to 23. -

UNITAR Hiroshima Fellowship for Afghanistan - Executive Report 2009

18 - 23 April 2010 Hiroshima, Japan Executive Summary UNITAR Series The Management and Conservation of World Heritage Sites Hiroshima, Japan 18 – 23 April 2010 © 2010 The United Nations Institute for Training and Research ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The United Nations Institute for Training and Research (UNITAR) would like to express its deep gratitude to: - The Hiroshima Prefectural Government for its support of this Series since 2003 - The City of Hiroshima - Itsukushima Shinto Shrine - The Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum - The people of Hiroshima - The United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) and its World Heritage Centre (WHC); - The International Council on Monuments and Sites (ICOMOS); - The Getty Conservation Institute (GCI); - The World Conservation Union (IUCN); - The University of Hiroshima; - The University of Hyogo; - The Australian Government through the Department of the Environment, Water, Heritage and the Arts (DEWHA); - The Government of New Zealand through the New Zealand Department of Conservation – Te Papa Atawhai; - The United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) Our special thanks go to the Faculty and participants who contributed their time and expertise to the Session so graciously, and finally to the alumni and friends of UNITAR in Hiroshima and around the world whose cooperation was indispensable for the successful conduct of the 2010 Cycle. Berin McKenzie Hiroshima 2010 ii UNITAR Hiroshima Fellowship for Afghanistan - Executive Report 2009 UNITAR Series The Management and Conservation of World Heritage Sites Hiroshima, Japan 18 – 23 April 2010 INTRODUCTION The UNITAR Series on the Management heritage management. and Conservation of World Heritage Sites, Throughout this development arc, the represents a key pillar of the Institute‟s Series has developed innovative Hiroshima Office (HO) training approaches to heritage conservation, programme. -

Kyushu,Yamaguchi

World Heritage information facilities Iron Coal World Heritage information facilities Iron Coal Infancy and Steel Shipbuilding Mining Infancy and Steel Shipbuilding Mining ew Photo Local tourism information facilities Local tourism information facilities UNESCO World Heritage Vi s Kitakyushu City, Fukuoka pref./Nakama City, Fukuoka pref. Saga City, Saga pref. YAWATA Shokasonjuku SAGA Academy The first modern integrated iron and steel works in Japan A base for the acquisition and practice of Western shipbuilding techniques AR Map The imperial Steel Works,Japan Mietsu Naval Dock First Head Office 30 minutes by city bus from JR Saga Station Bus Shoin Yoshida Viewing space : 10 minute walk from Space Center, and a five minute walk from Sano Tsunetami Kinen- Kyushu,Yamaguchi ● World Station on the JR Kagoshima Main Line (Take the N 1: 900,000 0 10 20㎞ kan Iriguchi bus stop 30 minutes by Nishitetsu Bus from underground passageway facing the entrance to Space Hagi Iwami Airport Nishitetsu- Yanagawa Station, and a five minute walk from World ) *the inner area isn't open to the public 191 Hayatsue bus stop, the final stop a ©Yawata Works, to c r na ● it v NIPPON STEEL & ● Edamitsu, Yahatahigashi-ku, Kitakyushu-city, Fukuoka Key Component Part Toll Road OazaHayatsuetsu, Kawasoe-town/OazaTameshige, ig SUMITOMO METAL Morodomi-town, Saga-city, Saga m a CORPORATION s t ☎ 093-541-4189 Interchange n i a o City of the Component Part ☎ 0952-40-7105 n Junction Choshu Five r Shimane Prefecture Tsunetami Sano Memorial Museum 0952-34-9455 T [ Not open to the public] -

List of LIXIL's ISO14001 Certified Plants(As of March 2021)

List of LIXIL's ISO14001 certified plants(As of March 2021) LIXIL Water Technology Japan 22 sites Chita plant、Chita plant service parts center, Enokido plant, Otani plant, LIXIL Oyama Manufacturing Co., Ltd., Oyama plant, SAGA LIXIL Factory Corporation Kashima plant, Tsukuba plant, Tsukuba plant Chiba manufacturing department, Sapporo plant, Ueno Midori plant, SAGA LIXIL Factory Corporation Saga plant, Handa plant, Onomichi plant, HIKONE LIXIL Factory Corporation Hikone plant, Tokoname east plant, Tokoname east plant Higashiura manufacturing, Iga Ueno plant, Seto plant, Akechi plant, LIXIL Sunwave Factory Corporation Fukaya plant, LIXIL Sunwave Factory Corporation Kiryu plant, LIXIL Sunwave Factory Corporation Yashiro plant, Kani LIXIL Sunwave Factory Corporation Kani plant, Eco Center Tokoname,LIXIL Sanitary Fitting Manufacturing (Suzhou) LIXIL Housing Technology Japan 25 sites Iwai plant, Yokohama LIXIL Factory Corporation Yokohama plant, Yamato LIXIL Factory Corporation Yamato plant, Shimotsuma plant, Shimotsuma plant Kanuma Panel Center, Ichinoseki LIXIL Factory Corporation Ichinoseki plant, Hokkaido LIXIL Factory Corporation Kurisawa plant, Ibuki LIXIL Factory Corporation Ibuki plant, Hisai LIXIL Factory Corporation Hisai plant, Nabari plant, Ishige plant, Okinawa LIXIL Factory Corporation Okinawa plant, Ariake plant, Tsuchiura plant, Shinnikkei Hokuriku Corporation Oyabe plant, Exterior OEM center, Maebashi LIXIL Factory Corporation Kasukawa plant, Maebashi LIXIL Factory Corporation Maebashi plant, Fukushima LIXIL Factory Corporation -

W E Lcom E to Saga Balloon M Useum !

Saga Yamato IC Karatsu & Nagasaki Nagasaki Main Line Tosu & Fukuoka ga Ba JR Saga Station a llo Saga-eki S o Bus Center o n Saga t City Hall M Don-Don-Don e no Mori u Tenjinbashi Tojin 1- c h o m e K i t a m s o “Saga Balloon Museum” e Muraoka The Bank of c u Tenjin Post Office Nishi Sohonpo Saga, Headquarters l Tojin 1-chome Minami e was opened to relay m Odori Chuo information about balloons to ! S-Platz W many people! 656 Plaza Saga City Ballooning is a wind-dependent sport. Saga Tamaya Cultural Museum Saga Balloon Even though Saga City is known as Parking Entrance Museum Saga Ebisu Station “The City of Hot Air Balloons”, Matsubara 2-chome Bus Stop Parking Exit Matsubara Shrine balloons are not flying all year round. “Kenchomae” Chokokan Saga Saga Shrine Prefectural Experience ballooning no matter the weather! Yokamachi Police Chuo Post Office Katatae Post Office Sagajinja Kado Learn amazing, new information about balloons! Saga Prefectural Prefectural See how cool sky sports are!! Office Library Prefectural Saga Castle Okuma Memorial Experience the joys of ballooning through Museum / History Museum Museum many discoveries and inspirations at Art Museum Saga Balloon Museum! From JR Saga Station To Fukuoka ・Walk 17-min. Towards Saga Saga Yamato IC Prefectural Office Nagasaki Expressway ・5-min. by Bus from Saga-eki Bus To Nagasaki Center on Saga City Bus, Showa Bus, or Yutoku Bus̶Get Off at “Kenchomae” Bus Stop & Walk To Karatsu Saga 1-min. Athletic To Tosu Karatsu Line Stadium ・5-min. -

Higashiyoka-Higata

Tidal mudfl at in the innermost part of Ariake Sea, one of the largest habitats for migratory shorebirds Higashiyoka-higata Tidal Flat Geographical Coordinates: 33°10’N, 103°15’E / Altitude: -2.5 – 1m/ Area: 218ha / Major Type of Wetland: Tidal fl at / Designation: Special Protection Area of National Wildlife Protection Area / Municipalities Involved: Saga City, Saga Prefecture / Ramsar Designation: May 2015 / Ramsar Criteria: 2, 4, 6 Important habitat for migratory shorebirds (Photo by H. Yatsuki) Aerial view of Higashiyoka-higata from the southwest Saunders’s Gull (Photo by H. Yatsuki) walking trail along the seashore is a good place to observe countless life forms such as crabs and mudskippers at low tide. It is a breathtaking experience to see thousands of shorebirds fl y over toward the wetland and forage intently for food on the mudfl at during the migration season in spring and autumn. Conservation Efforts for the Tidal Flat Two groups were established recently, namely “Mudfl at Expedition” organized mainly by local people and “Higashiyoka A colony of Suaeda japonica in beautiful autumn red Ramsar Club” managed by Saga City. “Mud- fl at Expedition” has 30 members, who General Overview to the tidal current in the sea, settle down participate in such activities as bird watch- Higashiyoka-higata is a tidal mudfl at to accumulate when the current stops at ing and tidal fl at watching. “Higashiyoka located at the northern most shore of high tide and form a mudfl at when the sedi- Ramsar Club” has 45 members including Ariake Sea. It is an extensive tidal fl at in the ments are left at low tide. -

KAKEHASHI Project (United States of America) Inbound Program for University Students the 2Nd Slot Program Report

KAKEHASHI Project (United States of America) Inbound program for University students the 2nd Slot Program Report 1. Program Overview Under the “KAKEHASHI Project” of Japan’s Friendship Ties Program, 75 university students and supervisors from the U.S. visited Japan from March 10 to March 19, 2019 to participate in the program aimed at promoting their understanding of Japan with regard to Japanese politics, economy, society, culture, history, and foreign policy. Through the lectures, observations and interactions with Japanese people etc., the participants enjoyed a wide range of opportunities to improve their understanding of Japan and shared their individual interests and experiences on social media. Based on their findings and learning in Japan, each group of participants made a presentation in the final session and reported on the action plans to be taken after returning to the U.S. 【Participating Countries and Numbers of Participants】 United States of America: 75 participants (Breakdown) Group A (25 participants):Haverford College, Bryn Mawr College, Villanova University, Ursinus College (State of Pennsylvania) Group B (25 participants):George Washington University (District of Columbia) Group C (25 participants):University of North Georgia (State of Georgia) 【Prefectures Visited】 Tokyo (All), Aomori (Group A), Shiga (Group B), Saga (Group C) 2. Program Schedule Group A Group B Group C Mar.10 Arrival (Sun) Mar.11 【Lecture】Mr. Jason P. Hyland, Representative Officer and President of MGM (Mon) Resorts Japan, Former Charged Affaires