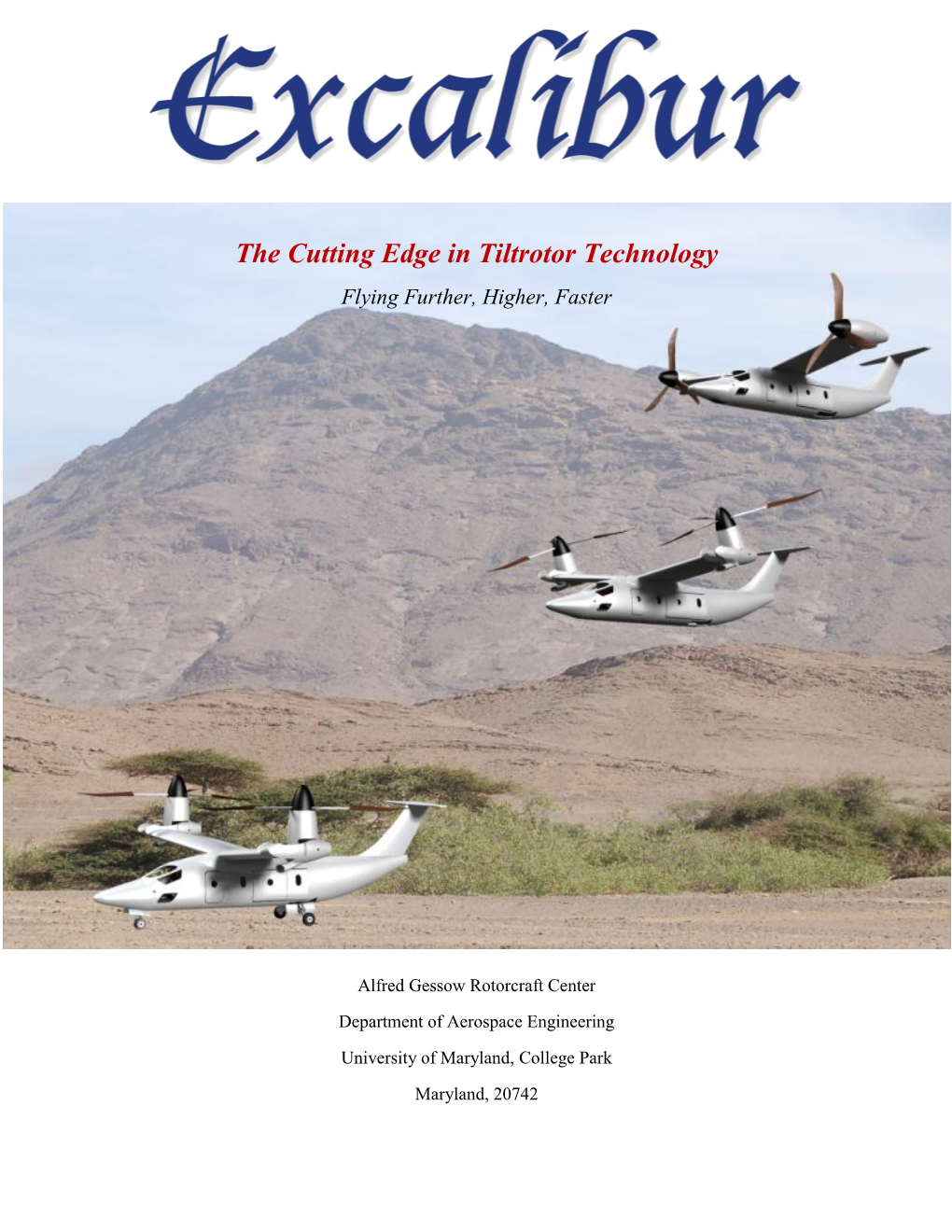

The Cutting Edge in Tiltrotor Technology Flying Further, Higher, Faster

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Jay Carter, Founder &

CARTER AVIATION TECHNOLOGIES An Aerospace Research & Development Company Jay Carter, Founder & CEO CAFE Electric Aircraft Symposium www.CarterCopters.com July 23rd, 2017 Wichita©2015 CARTER AVIATIONFalls, TECHNOLOGIES,Texas LLC SR/C is a trademark of Carter Aviation Technologies, LLC1 A History of Innovation Built first gyros while still in college with father’s guidance Led to job with Bell Research & Development Steam car built by Jay and his father First car to meet original 1977 emission standards Could make a cold startup & then drive away in less than 30 seconds Founded Carter Wind Energy in 1976 Installed wind turbines from Hawaii to United Kingdom to 300 miles north of the Arctic Circle One of only two U.S. manufacturers to survive the mid ‘80s industry decline ©2015 CARTER AVIATION TECHNOLOGIES, LLC 2 SR/C™ Technology Progression 2013-2014 DARPA TERN Won contract over 5 majors 2009 License Agreement with AAI, Multiple Military Concepts 2011 2017 2nd Gen First Flight Find a Manufacturing Later Demonstrated Partner and Begin 2005 L/D of 12+ Commercial Development 1998 1 st Gen 1st Gen L/D of 7.0 First flight 1994 - 1997 Analysis & Component Testing 22 years, 22 patents + 5 pending 1994 Company 11 key technical challenges overcome founded Proven technology with real flight test ©2015 CARTER AVIATION TECHNOLOGIES, LLC 3 SR/C™ Technology Progression Quiet Jump Takeoff & Flyover at 600 ft agl Video also available on YouTube: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=_VxOC7xtfRM ©2015 CARTER AVIATION TECHNOLOGIES, LLC 4 SR/C vs. Fixed Wing • SR/C rotor very low drag by being slowed Profile HP vs. -

Loss of Control in Yaw During Take-Off, Collision with the Ground, in Sightseeing Flight

INVESTIGATION REPORT www.bea.aero Accident involving Airbus Helicopters EC130 B4 registered F-GOLH on 24 October 2015 at Megève (74) (1)Unless otherwise Time At 11:45(1) specified, the times in this report Operator Mont-Blanc Hélicoptère MBH are expressed Type of flight Commercial air transport in local time. Persons on board Pilot and six passengers Two passengers injured, the pilot and four Consequences and damage passengers slightly injured, helicopter destroyed Loss of control in yaw during take-off, collision with the ground, in sightseeing flight 1 - HISTORY OF THE FLIGHT During the morning, the pilot made several “Mont Blanc” sightseeing flights with the same helicopter from Megève altiport. During take-off for the fourth flight and as for the previous flights, he stabilized the helicopter in hover in the ground effect and then began to rotate it to the left around its yaw axis in order to face the climb-out path. During this manoeuvre, the pilot lost the yaw control of the aircraft, which turned several times on itself before crashing below a slope adjacent to the take-off area. The BEA investigations are conducted with the sole objective of improving aviation safety and are not intended to apportion blame or liabilities. 1/9 BEA-0647.en/January 2018 2 - ADDITIONAL INFORMATION 2.1 Examination of the accident site and wreckage The wreckage is located 25 meters to the north-north/west below the take-off area. Observations indicate that the engine was providing power and that the rotor struck the ground with energy. The cyclic pitch and collective pitch controls are continuous. -

Complexity” Makes a Difference: Lessons from Critical Systems Thinking and the Covid-19 Pandemic in the UK

systems Article How We Understand “Complexity” Makes a Difference: Lessons from Critical Systems Thinking and the Covid-19 Pandemic in the UK Michael C. Jackson Centre for Systems Studies, University of Hull, Hull HU6 7TS, UK; [email protected]; Tel.: +44-7527-196400 Received: 11 November 2020; Accepted: 4 December 2020; Published: 7 December 2020 Abstract: Many authors have sought to summarize what they regard as the key features of “complexity”. Some concentrate on the complexity they see as existing in the world—on “ontological complexity”. Others highlight “cognitive complexity”—the complexity they see arising from the different interpretations of the world held by observers. Others recognize the added difficulties flowing from the interactions between “ontological” and “cognitive” complexity. Using the example of the Covid-19 pandemic in the UK, and the responses to it, the purpose of this paper is to show that the way we understand complexity makes a huge difference to how we respond to crises of this type. Inadequate conceptualizations of complexity lead to poor responses that can make matters worse. Different understandings of complexity are discussed and related to strategies proposed for combatting the pandemic. It is argued that a “critical systems thinking” approach to complexity provides the most appropriate understanding of the phenomenon and, at the same time, suggests which systems methodologies are best employed by decision makers in preparing for, and responding to, such crises. Keywords: complexity; Covid-19; critical systems thinking; systems methodologies 1. Introduction No one doubts that we are, in today’s world, entangled in complexity. At the global level, economic, social, technological, health and ecological factors have become interconnected in unprecedented ways, and the consequences are immense. -

Sept. 12, 1950 W

Sept. 12, 1950 W. ANGST 2,522,337 MACH METER Filed Dec. 9, 1944 2 Sheets-Sheet. INVENTOR. M/2 2.7aar alwg,57. A77OAMA). Sept. 12, 1950 W. ANGST 2,522,337 MACH METER Filed Dec. 9, 1944 2. Sheets-Sheet 2 N 2 2 %/ NYSASSESSN S2,222,W N N22N \ As I, mtRumaIII-m- III It's EARAs i RNSITIE, 2 72/ INVENTOR, M247 aeawosz. "/m2.ATTORNEY. Patented Sept. 12, 1950 2,522,337 UNITED STATES ; :PATENT OFFICE 2,522,337 MACH METER Walter Angst, Manhasset, N. Y., assignor to Square D Company, Detroit, Mich., a corpora tion of Michigan Application December 9, 1944, Serial No. 567,431 3 Claims. (Cl. 73-182). is 2 This invention relates to a Mach meter for air plurality of posts 8. Upon one of the posts 8 are craft for indicating the ratio of the true airspeed mounted a pair of serially connected aneroid cap of the craft to the speed of sound in the medium sules 9 and upon another of the posts 8 is in which the aircraft is traveling and the object mounted a diaphragm capsuler it. The aneroid of the invention is the provision of an instrument s: capsules 9 are sealed and the interior of the cas-l of this type for indicating the Mach number of an . ing is placed in communication with the static aircraft in fight. opening of a Pitot static tube through an opening The maximum safe Mach number of any air in the casing, not shown. The interior of the dia craft is the value of the ratio of true airspeed to phragm capsule is connected through the tub the speed of sound at which the laminar flow of ing 2 to the Pitot or pressure opening of the Pitot air over the wings fails and shock Waves are en static tube through the opening 3 in the back countered. -

Design, Modelling and Control of a Space UAV for Mars Exploration

Design, Modelling and Control of a Space UAV for Mars Exploration Akash Patel Space Engineering, master's level (120 credits) 2021 Luleå University of Technology Department of Computer Science, Electrical and Space Engineering Design, Modelling and Control of a Space UAV for Mars Exploration Akash Patel Department of Computer Science, Electrical and Space Engineering Faculty of Space Science and Technology Luleå University of Technology Submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the Degree of Masters in Space Science and Technology Supervisor Dr George Nikolakopoulos January 2021 Acknowledgements I would like to take this opportunity to thank my thesis supervisor Dr. George Nikolakopoulos who has laid a concrete foundation for me to learn and apply the concepts of robotics and automation for this project. I would be forever grateful to George Nikolakopoulos for believing in me and for supporting me in making this master thesis a success through tough times. I am thankful to him for putting me in loop with different personnel from the robotics group of LTU to get guidance on various topics. I would like to thank Christoforos Kanellakis for guiding me in the control part of this thesis. I would also like to thank Björn Lindquist for providing me with additional research material and for explaining low level and high level controllers for UAV. I am grateful to have been a part of the robotics group at Luleå University of Technology and I thank the members of the robotics group for their time, support and considerations for my master thesis. I would also like to thank Professor Lars-Göran Westerberg from LTU for his guidance in develop- ment of fluid simulations for this master thesis project. -

Dissipative Structures, Complexity and Strange Attractors: Keynotes for a New Eco-Aesthetics

Dissipative structures, complexity and strange attractors: keynotes for a new eco-aesthetics 1 2 3 3 R. M. Pulselli , G. C. Magnoli , N. Marchettini & E. Tiezzi 1Department of Urban Studies and Planning, M.I.T, Cambridge, U.S.A. 2Faculty of Engineering, University of Bergamo, Italy and Research Affiliate, M.I.T, Cambridge, U.S.A. 3Department of Chemical and Biosystems Sciences, University of Siena, Italy Abstract There is a new branch of science strikingly at variance with the idea of knowledge just ended and deterministic. The complexity we observe in nature makes us aware of the limits of traditional reductive investigative tools and requires new comprehensive approaches to reality. Looking at the non-equilibrium thermodynamics reported by Ilya Prigogine as the key point to understanding the behaviour of living systems, the research on design practices takes into account the lot of dynamics occurring in nature and seeks to imagine living shapes suiting living contexts. When Edgar Morin speaks about the necessity of a method of complexity, considering the evolutive features of living systems, he probably means that a comprehensive method should be based on deep observations and flexible ordering laws. Actually designers and planners are engaged in a research field concerning fascinating theories coming from science and whose playground is made of cities, landscapes and human settlements. So, the concept of a dissipative structure and the theory of space organized by networks provide a new point of view to observe the dynamic behaviours of systems, finally bringing their flowing patterns into the practices of design and architecture. However, while science discovers the fashion of living systems, the question asked is how to develop methods to configure open shapes according to the theory of evolutionary physics. -

Real-Time Helicopter Flight Control: Modelling and Control by Linearization and Neural Networks

Purdue University Purdue e-Pubs Department of Electrical and Computer Department of Electrical and Computer Engineering Technical Reports Engineering August 1991 Real-Time Helicopter Flight Control: Modelling and Control by Linearization and Neural Networks Tobias J. Pallett Purdue University School of Electrical Engineering Shaheen Ahmad Purdue University School of Electrical Engineering Follow this and additional works at: https://docs.lib.purdue.edu/ecetr Pallett, Tobias J. and Ahmad, Shaheen, "Real-Time Helicopter Flight Control: Modelling and Control by Linearization and Neural Networks" (1991). Department of Electrical and Computer Engineering Technical Reports. Paper 317. https://docs.lib.purdue.edu/ecetr/317 This document has been made available through Purdue e-Pubs, a service of the Purdue University Libraries. Please contact [email protected] for additional information. Real-Time Helicopter Flight Control: Modelling and Control by Linearization and Neural Networks Tobias J. Pallett Shaheen Ahmad TR-EE 91-35 August 1991 Real-Time Helicopter Flight Control: Modelling and Control by Lineal-ization and Neural Networks Tobias J. Pallett and Shaheen Ahmad Real-Time Robot Control Laboratory, School of Electrical Engineering, Purdue University West Lafayette, IN 47907 USA ABSTRACT In this report we determine the dynamic model of a miniature helicopter in hovering flight. Identification procedures for the nonlinear terms are also described. The model is then used to design several linearized control laws and a neural network controller. The controllers were then flight tested on a miniature helicopter flight control test bed the details of which are also presented in this report. Experimental performance of the linearized and neural network controllers are discussed. -

Electrically Heated Composite Leading Edges for Aircraft Anti-Icing Applications”

UNIVERSITY OF NAPLES “FEDERICO II” PhD course in Aerospace, Naval and Quality Engineering PhD Thesis in Aerospace Engineering “ELECTRICALLY HEATED COMPOSITE LEADING EDGES FOR AIRCRAFT ANTI-ICING APPLICATIONS” by Francesco De Rosa 2010 To my girlfriend Tiziana for her patience and understanding precious and rare human virtues University of Naples Federico II Department of Aerospace Engineering DIAS PhD Thesis in Aerospace Engineering Author: F. De Rosa Tutor: Prof. G.P. Russo PhD course in Aerospace, Naval and Quality Engineering XXIII PhD course in Aerospace Engineering, 2008-2010 PhD course coordinator: Prof. A. Moccia ___________________________________________________________________________ Francesco De Rosa - Electrically Heated Composite Leading Edges for Aircraft Anti-Icing Applications 2 Abstract An investigation was conducted in the Aerospace Engineering Department (DIAS) at Federico II University of Naples aiming to evaluate the feasibility and the performance of an electrically heated composite leading edge for anti-icing and de-icing applications. A 283 [mm] chord NACA0012 airfoil prototype was designed, manufactured and equipped with an High Temperature composite leading edge with embedded Ni-Cr heating element. The heating element was fed by a DC power supply unit and the average power densities supplied to the leading edge were ranging 1.0 to 30.0 [kW m-2]. The present investigation focused on thermal tests experimentally performed under fixed icing conditions with zero AOA, Mach=0.2, total temperature of -20 [°C], liquid water content LWC=0.6 [g m-3] and average mean volume droplet diameter MVD=35 [µm]. These fixed conditions represented the top icing performance of the Icing Flow Facility (IFF) available at DIAS and therefore it has represented the “sizing design case” for the tested prototype. -

No Acoustical Change” for Propeller-Driven Small Airplanes and Commuter Category Airplanes

4/15/03 AC 36-4C Appendix 4 Appendix 4 EQUIVALENT PROCEDURES AND DEMONSTRATING "NO ACOUSTICAL CHANGE” FOR PROPELLER-DRIVEN SMALL AIRPLANES AND COMMUTER CATEGORY AIRPLANES 1. Equivalent Procedures Equivalent Procedures, as referred to in this AC, are aircraft measurement, flight test, analytical or evaluation methods that differ from the methods specified in the text of part 36 Appendices A and B, but yield essentially the same noise levels. Equivalent procedures must be approved by the FAA. Equivalent procedures provide some flexibility for the applicant in conducting noise certification, and may be approved for the convenience of an applicant in conducting measurements that are not strictly in accordance with the 14 CFR part 36 procedures, or when a departure from the specifics of part 36 is necessitated by field conditions. The FAA’s Office of Environment and Energy (AEE) must approve all new equivalent procedures. Subsequent use of previously approved equivalent procedures such as flight intercept typically do not need FAA approval. 2. Acoustical Changes An acoustical change in the type design of an airplane is defined in 14 CFR section 21.93(b) as any voluntary change in the type design of an airplane which may increase its noise level; note that a change in design that decreases its noise level is not an acoustical change in terms of the rule. This definition in section 21.93(b) differs from an earlier definition that applied to propeller-driven small airplanes certificated under 14 CFR part 36 Appendix F. In the earlier definition, acoustical changes were restricted to (i) any change or removal of a muffler or other component of an exhaust system designed for noise control, or (ii) any change to an engine or propeller installation which would increase maximum continuous power or propeller tip speed. -

Adventures in Low Disk Loading VTOL Design

NASA/TP—2018–219981 Adventures in Low Disk Loading VTOL Design Mike Scully Ames Research Center Moffett Field, California Click here: Press F1 key (Windows) or Help key (Mac) for help September 2018 This page is required and contains approved text that cannot be changed. NASA STI Program ... in Profile Since its founding, NASA has been dedicated • CONFERENCE PUBLICATION. to the advancement of aeronautics and space Collected papers from scientific and science. The NASA scientific and technical technical conferences, symposia, seminars, information (STI) program plays a key part in or other meetings sponsored or co- helping NASA maintain this important role. sponsored by NASA. The NASA STI program operates under the • SPECIAL PUBLICATION. Scientific, auspices of the Agency Chief Information technical, or historical information from Officer. It collects, organizes, provides for NASA programs, projects, and missions, archiving, and disseminates NASA’s STI. The often concerned with subjects having NASA STI program provides access to the NTRS substantial public interest. Registered and its public interface, the NASA Technical Reports Server, thus providing one of • TECHNICAL TRANSLATION. the largest collections of aeronautical and space English-language translations of foreign science STI in the world. Results are published in scientific and technical material pertinent to both non-NASA channels and by NASA in the NASA’s mission. NASA STI Report Series, which includes the following report types: Specialized services also include organizing and publishing research results, distributing • TECHNICAL PUBLICATION. Reports of specialized research announcements and feeds, completed research or a major significant providing information desk and personal search phase of research that present the results of support, and enabling data exchange services. -

Helicopter Physics by Harm Frederik Althuisius López

Helicopter Physics By Harm Frederik Althuisius López Lift Happens Lift Formula Torque % & Lift is a mechanical aerodynamic force produced by the Lift is calculated using the following formula: 2 = *4 '56 Torque is a measure of how much a force acting on an motion of an aircraft through the air, it generally opposes & object causes that object to rotate. As the blades of a Where * is the air density, 4 is the velocity, '5 is the lift coefficient and 6 is gravity as a means to fly. Lift is generated mainly by the the surface area of the wing. Even though most of these components are helicopter rotate against the air, the air pushes back on the rd wings due to their shape. An Airfoil is a cross-section of a relatively easy to measure, the lift coefficient is highly dependable on the blades following Newtons 3 Law of Motion: “To every wing, it is a streamlined shape that is capable of generating shape of the airfoil. Therefore it is usually calculated through the angle of action there is an equal and opposite reaction”. This significantly more lift than drag. Drag is the air resistance attack of a specific airfoil as portrayed in charts much like the following: reaction force is translated into the fuselage of the acting as a force opposing the motion of the aircraft. helicopter via torque, and can be measured for individual % & -/ 0 blades as follows: ! = #$ = '()*+ ∫ # 1# , where $ is the & -. Drag Force. As a result the fuselage tends to rotate in the Example of a Lift opposite direction of its main rotor spin. -

Aircraft Winglet Design

DEGREE PROJECT IN VEHICLE ENGINEERING, SECOND CYCLE, 15 CREDITS STOCKHOLM, SWEDEN 2020 Aircraft Winglet Design Increasing the aerodynamic efficiency of a wing HANLIN GONGZHANG ERIC AXTELIUS KTH ROYAL INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY SCHOOL OF ENGINEERING SCIENCES 1 Abstract Aerodynamic drag can be decreased with respect to a wing’s geometry, and wingtip devices, so called winglets, play a vital role in wing design. The focus has been laid on studying the lift and drag forces generated by merging various winglet designs with a constrained aircraft wing. By using computational fluid dynamic (CFD) simulations alongside wind tunnel testing of scaled down 3D-printed models, one can evaluate such forces and determine each respective winglet’s contribution to the total lift and drag forces of the wing. At last, the efficiency of the wing was furtherly determined by evaluating its lift-to-drag ratios with the obtained lift and drag forces. The result from this study showed that the overall efficiency of the wing varied depending on the winglet design, with some designs noticeable more efficient than others according to the CFD-simulations. The shark fin-alike winglet was overall the most efficient design, followed shortly by the famous blended design found in many mid-sized airliners. The worst performing designs were surprisingly the fenced and spiroid designs, which had efficiencies on par with the wing without winglet. 2 Content Abstract 2 Introduction 4 Background 4 1.2 Purpose and structure of the thesis 4 1.3 Literature review 4 Method 9 2.1 Modelling