Copyright by Hannah Claire Alberts 2016

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Foreign Observation of the Illegitimate Elections in South Ossetia and Abkhazia in 2019

FOREIGN OBSERVATION OF THE ILLEGITIMATE ELECTIONS IN SOUTH OSSETIA AND ABKHAZIA IN 2019 Anton Shekhovtsov FOREIGN OBSERVATION OF THE ILLEGITIMATE ELECTIONS IN SOUTH OSSETIA AND ABKHAZIA IN 2019 Anton Shekhovtsov Contents Executive summary _____________________________________ 4 Introduction: Illegitimacy of the South Ossetian “parliamentary” and Abkhaz “presidential elections” ___________ 6 “Foreign observers” of the 2019 “elections” in South Ossetia and Abkhazia ____________________________ 9 Established involvement of “foreign observers” in pro-Kremlin efforts __________________________________ 16 Assessments of the South Ossetian and Abkhaz 2019 “elections” by “foreign observers” _____________________ 21 Conclusion ___________________________________________ 27 Edition: European Platform for Democratic Elections www.epde.org Responsible for the content: Europäischer Austausch gGmbH Erkelenzdamm 59 10999 Berlin, Germany Represented through: Stefanie Schiffer EPDE is financially supported by the European Union and the Federal Foreign Office of Germany. The here expressed opinion does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the donors. Executive summary The so-called “Republic of South Ossetia” and “Republic of Abkhazia” are breakaway regions of Georgia that are recognised as independent sovereign states only by five UN Member States: Russia (which supports their de facto independence by military, economic and political means), Nauru, Nicaragua, Syria and Venezuela. Other entities that recognise South Ossetia and Abkhaz- ia as independent -

International Crimes in Crimea

International Crimes in Crimea: An Assessment of Two and a Half Years of Russian Occupation SEPTEMBER 2016 Contents I. Introduction 6 A. Executive summary 6 B. The authors 7 C. Sources of information and methodology of documentation 7 II. Factual Background 8 A. A brief history of the Crimean Peninsula 8 B. Euromaidan 12 C. The invasion of Crimea 15 D. Two and a half years of occupation and the war in Donbas 23 III. Jurisdiction of the International Criminal Court 27 IV. Contextual elements of international crimes 28 A. War crimes 28 B. Crimes against humanity 34 V. Willful killing, murder and enforced disappearances 38 A. Overview 38 B. The law 38 C. Summary of the evidence 39 D. Documented cases 41 E. Analysis 45 F. Conclusion 45 VI. Torture and other forms of inhuman treatment 46 A. Overview 46 B. The law 46 C. Summary of the evidence 47 D. Documented cases of torture and other forms of inhuman treatment 50 E. Analysis 59 F. Conclusion 59 VII. Illegal detention 60 A. Overview 60 B. The law 60 C. Summary of the evidence 62 D. Documented cases of illegal detention 66 E. Analysis 87 F. Conclusion 87 VIII. Forced displacement 88 A. Overview 88 B. The law 88 C. Summary of evidence 90 D. Analysis 93 E. Conclusion 93 IX. Crimes against public, private and cultural property 94 A. Overview 94 B. The law 94 C. Summary of evidence 96 D. Documented cases 99 E. Analysis 110 F. Conclusion 110 X. Persecution and collective punishment 111 A. Overview 111 B. -

Annex-To-Ukraine-News-Release-26-September-2016.Pdf

ANNEX TO NOTICE FINANCIAL SANCTIONS: UKRAINE (SOVEREIGNTY AND TERRITORIAL INTEGRITY) COUNCIL IMPLEMENTING REGULATION (EU) No 2016/1661 AMENDING ANNEX I TO COUNCIL REGULATION (EU) No 269/2014 AMENDMENTS Individuals 1. KONSTANTINOV, Vladimir, Andreevich DOB: 19/11/1956. POB: (1) Vladimirovka (a.k.a Vladimirovca), Slobozia Region, Moldavian SSR (now Republic of Moldova/Transnistria region (2) Bogomol, Moldaovian SSR, Republic of Moldova Position: Speaker of the Supreme Council of the Autonomous Republic of Crimea Other Information: Since 17 March 2014, KONSTANTINOV is Chairman of the State Council of the so-called Republic of Crimea. Listed on: 18/03/2014 Last Updated: 23/03/2016 17/09/2016 Group ID: 12923. 2. SIDOROV, Anatoliy, Alekseevich DOB: 02/07/1958. POB: Siva, Perm region, USSR Position: Chief of the Joint Staff of the Collective Security Treaty Organisation (CSTO) (Since November 2015). Commander, Russia’s Western Military District Other Information: Former Commander, Russia's Western Military District. Listed on: 18/03/2014 Last Updated: 21/09/2015 17/09/2016 Group ID: 12931 3. KOVITIDI, KOVATIDI Olga, Fedorovna DOB: 07/05/1962. POB: Simferopol, Ukrainian SSR Position: Member of the Russian Federation Council from the annexed Autonomous Republic of Crimea Listed on: 29/04/2014 Last Updated: 21/09/2015 17/09/2016 Group ID: 12954. 4. PONOMARIOV, Viacheslav DOB: 02/05/1965. POB: Sloviansk, Donetsk Oblast a.k.a: (1) PONOMAREV, Viacheslav, Vladimirovich (2) PONOMARYOV, Vyacheslav, Volodymyrovich Other Information: Former self-declared ‘People’s Mayor’ of Sloviansk (until 10 June 2014). Listed on: 12/05/2014 Last Updated: 23/03/2016 17/09/2016 Group ID: 12970. -

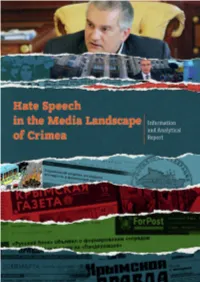

Hate Speech in the Media Landscape of Crimea

HATE SPEECH IN THE MEDIA LANDSCAPE OF CRIMEA AN INFORMATION AND ANALYTICAL REPORT ON THE SPREAD OF HATE SPEECH ON THE TERRITORY OF THE CRIMEAN PENINSULA (MARCH 2014 — JULY 2017) Kyiv — 2018 UDC 32.019.5:323.266:327(477.75+47 0) Authors: Oleksandr Burmahyn Tetiana Pechonchyk Iryna Sevoda Olha Skrypnyk Review: Viacheslav Lykhachev Translation: Anastasiia Morenets Proofreading: Steve Doyle Hate Speech in the Media Landscape of Crimea: An Information and Analytical Report on the Spread of Hate Speech on the Territory of the Crimean Peninsula (March 2014 – July 2017) / under the general editorship of I. Sedova and T. Pechonchyk. – Kyiv, 2018. — 40 p. ISBN 978-966-8977-81-7 This publication presents the outcome of documenting and classifying facts on the use of hate speech on the territory of the occupied Autonomous Republic of Crimea and city of Sevastopol from April 2014 to July 2017. This publication uses material from mass media that have been disseminated in the territory of Crimea since the occupation of the peninsula by the Russian Federation, as well as information from open sources, including information resources from the authorities of Ukraine, Russian Federation and Crimean de-facto authorities, Crimean Human Rights Group and Human Rights Information Centre. This publication is intended for the representatives of state authorities, educational and research institutions, diplomatic missions, international, non-governmental and human rights organizations Crimean Human Rights Group (CHRG) — is an organization of Crimean human rights defenders and journalists aimed at promoting the observance and protection of human rights in Crimea by documenting the violations of human rights and international humanitarian law on the territory of the Crimean peninsula as well as attracting wide attention to these issues and searching for methods and elaborating instruments to defend human rights in Crimea. -

Ukraine (Sovereignty and Territorial Integrity)

Financial Sanctions Notice 23/09/2016 Ukraine (Sovereignty and Territorial Integrity) Introduction 1. Council Regulation (EU) No 269/2014 (“the Regulation”) imposing financial sanctions with regard to Ukraine (Sovereignty and Territorial Integrity) has been amended. Notice summary (Full details are provided in the Annex to this Notice) 2. The 43 persons (33 individuals, 10 entities) in the Annex to this Notice have had their listing details amended and remain subject to an asset freeze. What you must do 3. You must: i. check whether you maintain any accounts or hold any funds or economic resources for the persons set out in the Annex to this Notice; ii. freeze such accounts, and other funds or assets; iii. refrain from dealing with the funds or assets or making them available to such persons unless licensed by the Office of Financial Sanctions Implementation (OFSI); iv. report any findings to OFSI, together with any additional information that would facilitate compliance with the Regulation; 1 v. provide any information concerning the frozen assets of designated persons that OFSI may request. Information reported to OFSI may be passed on to other regulatory authorities or law enforcement. 4. Where a relevant institution has already reported details of accounts, other funds or economic resources held frozen for designated persons, they are not required to report these details again. 5. Failure to comply with financial sanctions legislation or to seek to circumvent its provisions is a criminal offence. Legislative details 6. On 16 September 2016 Council Implementing Regulation (EU) No 2016/1661 (“the Amending Regulation”) was published in the Official Journal of the European Union by the Council of the European Union. -

Russia INDIVIDUALS

CONSOLIDATED LIST OF FINANCIAL SANCTIONS TARGETS IN THE UK Last Updated:01/07/2021 Status: Asset Freeze Targets REGIME: Russia INDIVIDUALS 1. Name 6: ABISOV 1: SERGEY 2: VADIMOVICH 3: n/a 4: n/a 5: n/a. Title: Minister DOB: 27/11/1967. POB: Simferopol, Crimea, Ukraine a.k.a: (1) ABISOV, Sergey, Vadymovych (2) ABISOV, Sergiy, Vadimovich (3) ABISOV, Sergiy, Vadymovych (4) ABISOV, Serhiy, Vadimovich (5) ABISOV, Serhiy, Vadymovych Nationality: Ukrainian Address: Crimea.Position: Minister of the Interior of the Republic Other Information: (UK Sanctions List Ref):RUS0061 Date designated on UK Sanctions List: 31/12/2020 (UK Statement of Reasons):By accepting his appointment as so-called ‘Minister of Interior of the Republic of Crimea’ by the President of Russia (decree No.301) on 5 May 2014 and by his actions as so-called ‘Minister of Interior’ he has undermined the territorial integrity, sovereignty and unity of Ukraine. Dismissed as so-called 'Minister of Interior of the 'Republic of Crimea' in June 2018.Aide to the 'Chairman' of the Council of ministers of the so-called 'Republic of Crimea'. (Gender):Male Listed on: 31/07/2014 Last Updated: 31/12/2020 Group ID: 13071. 2. Name 6: AIRAPETYAN 1: LARISA 2: LEONIDOVNA 3: n/a 4: n/a 5: n/a. DOB: 21/02/1970. POB: (possibly) Antratsit, Luhansk oblast, Ukraine a.k.a: (1) AIRAPETYAN, Larisa (2) AIRAPETYAN, Larysa (3) AYRAPETYAN, Larisa, Leonidovna (4) AYRAPETYAN, Larysa (5) HAYRAPETYAN, Larisa, Leonidovna (6) HAYRAPETYAN, Larysa Address: Ukraine.Other Information: (UK Sanctions List Ref):RUS0062 Date designated on UK Sanctions List: 31/12/2020 (Further Identifiying Information):Relatives/business associates or partners/links to listed individuals: Husband – Geran Hayrapetyan aka Ayrapetyan (UK Statement of Reasons):Former so-called “Health Minister’ of the so called ‘Luhansk People's Republic’. -

Romanov News Новости Романовых

Romanov News Новости Романовых By Ludmila & Paul Kulikovsky August-September 2016 Empress Maria Feodorovna Painting by Ivan Nicholaevich Kramskoi. 1881. The 10th anniversary of the reburial of Empress Marie Feodorovna Ten years ago, September 28, 2006, Empress Marie Feodorovna was buried in Russia in the St. Peter and Paul Cathedral, next to her husband Emperor Alexander III. The reburial of Empress Marie Feodorovna started in Denmark, in Roskilde Cathedral on September 23, in the presence of Her Majesty Queen Margrethe II of Denmark and the entire Danish Royal family, and the main part of the Romanov family members. Empress Marie Feodorovna’s coffin had been standing in the crypt of the Roskilde Cathedral, west of Copenhagen, for 78 years and now it was time for her return to her beloved husband Emperor Alexander III and the country she loved so much. On September 26, onboard the Danish Frigate Esben Snare the coffin with remains of Empress Maria Feodorovna, escorted by Princess and Prince Dimitri Romanovich Romanov and Paul Kulikovsky, arrived in Peterhof, where it was received by both the members of the Romanov family who had participated in Denmark and those who had gone straight to St. Petersburg. After the arrival ceremony with a military band playing and the Russian guards in parade uniforms, the coffin was placed in the Gothic Chapel in Alexandria Park (Peterhof) on lit de parade for one day, allowing people to pay their respect. On September 28, 2006, the coffin went via Tsarskoe Selo, to St. Isaac Cathedral, where Patriarch Alexei II served liturgy and panihida, and then finally it arrived in St. -

Greeks in Ukraine: from Ancient to Modern Times Svitlana Arabadzhy (Translated by Lina Smyk)

AHIF P O L I C Y J O U R N A L Spring 2015 Greeks in Ukraine: From Ancient to Modern Times Svitlana Arabadzhy (Translated by Lina Smyk) reeks have been living on the territory of modern Ukraine since ancient times. G They first settled in the area in the seventh century BCE as the result of ancient Greek colonization. Most of those immigrants were natives of Miletus and other cities in Ionia. According to the information provided by ancient authors, more than 60 colonies were founded by Greeks on the territory of modern Ukraine and Crimea. The most popular of those were Olvia, Tyr, Feodosia (Theodosia), Tauric Chersonese, Kerkenitida (territory of Yevpatoria) etc. These ancient Greek settlements left behind a rich and diverse heritage. They were the first states on the modern Ukrainian territory that became activators of social and political development for local tribes; for example, they speeded up the formation of state institutions which included elements from both Greek and other ethnicities. In the middle of the third century CE, the invasions by Goths and other tribes devastated the Greek cities. At a later time the appearance of Hun tribes in the Black Sea region and Migration Period in fourth and fifth centuries put the life of ancient Greek “polises” (city-states) on the territory of Ukraine to a complete end. The only city that was not destroyed was Tauric Chersonese, protected with strong defensive walls. In the fifth century, it became a part of Byzantine Empire and long served as a center of Greek life on the Crimea peninsular. -

Institutionally Blind? International Organisations and Human Rights Abuses in the Former Soviet Union

Institutionally blind? International organisations and human rights abuses in the former Soviet Union Edited by Adam Hug Institutionally blind? International organisations and human rights abuses in the former Soviet Union Edited by Adam Hug First published in February 2016 by The Foreign Policy Centre (FPC) Unit 1.9, First Floor, The Foundry 17 Oval Way, Vauxhall, London SE11 5RR www.fpc.org.uk [email protected] © Foreign Policy Centre 2016 All rights reserved ISBN-978-1-905833-29-0 ISBN- 1-905833-29-6 Disclaimer: The views expressed in this publication are those of the authors alone and do not represent the views of The Foreign Policy Centre or the Open Society Foundations. Printing by Intype Libra Cover art by Copyprint This project is kindly supported by the Open Society Foundations 1 Acknowledgements The editor would like to thank all of the authors who have kindly contributed to this collection and provided invaluable support in developing the project. In addition the editor is very grateful for the advice and guidance of a number of different experts including: Dame Audrey Glover, Anna Walker, Rita Patrício, Veronika Szente Goldston, Vladimir Shkolnikov and a number of others who prefer to remain anonymous. He would like to thank colleagues at the Open Society Foundations for all their help and support without which this project would not have been possible, most notably Michael Hall, Anastasiya Hozyainova, Viorel Ursu and Eleanor Kelly. As always he is indebted to the support of his colleagues at the Foreign Policy Centre, in particular Deniz Ugur. 2 Institutionally blind? Executive Summary Institutionally blind? examines whether some of the major international institutions covering the former Soviet Union (FSU) are currently meeting their human rights commitments. -

Advocates Under Occupation Situation with Observing the Advocates’ Rights in the Context of the Armed Conflict in Ukraine

Advocates Report under occupation Situation with observing the advocates’ rights in the context of the armed conflict in Ukraine Kyiv 2018 Advocates under occupation Situation with observing the advocates’ rights in the context of the armed conflict in Ukraine CONTENTS ABBREVIATIONS 4 FOREWORD 5 Section І. KEY STANDARDS AND GUARANTEES FOR THE ADVOCATES’ PROFESSIONAL PRACTICE 7 Section ІІ. VIOLATIONS OF THE RIGHTS AND GUARANTEES OF ADVOCATES’ PRACTICE IN THE CONTEXT OF THE ARMED CONFLICT IN UKRAINE 14 Brief overview of the situation related to occupation of Crimea and its effects on advocates’ practice 15 Violations of the rights and guarantees of the advocates’ practice at the occupied territory of the Autonomous Republic of Crimea and city of Sevastopol 17 This Report contains an analysis of the situation with the observance of the rights of lawyers in the context of the armed conflict in the Autonomous Republic of Crimea and the city of Sevastopol, as Brief overview of the situation with the armed well as in certain areas of Donetsk and Luhansk oblasts of Ukraine in 2014-2018. conflict at eastern Ukraine 27 It contains facts reflecting the actual situation of the bar in the occupied territories, as well as Effects of the armed conflict on the situation with observance the state of protection of the rights of lawyers from the occupied territories by Ukrainian bar self- of the advocates’ rights and guarantees at the occupied government bodies. territories of Donetsk and Luhansk oblasts 28 The authors also provide recommendations on how to improve the situation with the observance Section ІІІ. -

B COUNCIL REGULATION (EU) No 269/2014 of 17

02014R0269 — EN — 12.09.2020 — 028.001 — 1 This text is meant purely as a documentation tool and has no legal effect. The Union's institutions do not assume any liability for its contents. The authentic versions of the relevant acts, including their preambles, are those published in the Official Journal of the European Union and available in EUR-Lex. Those official texts are directly accessible through the links embedded in this document ►B COUNCIL REGULATION (EU) No 269/2014 of 17 March 2014 concerning restrictive measures in respect of actions undermining or threatening the territorial integrity, sovereignty and independence of Ukraine (OJ L 78, 17.3.2014, p. 6) Amended by: Official Journal No page date ►M1 Council Implementing Regulation (EU) No 284/2014 of 21 March L 86 27 21.3.2014 2014 ►M2 Council Implementing Regulation (EU) No 433/2014 of 28 April 2014 L 126 48 29.4.2014 ►M3 Council Regulation (EU) No 476/2014 of 12 May 2014 L 137 1 12.5.2014 ►M4 Council Implementing Regulation (EU) No 477/2014 of 12 May 2014 L 137 3 12.5.2014 ►M5 Council Implementing Regulation (EU) No 577/2014 of 28 May 2014 L 160 7 29.5.2014 ►M6 Council Implementing Regulation (EU) No 753/2014 of 11 July 2014 L 205 7 12.7.2014 ►M7 Council Regulation (EU) No 783/2014 of 18 July 2014 L 214 2 19.7.2014 ►M8 Council Implementing Regulation (EU) No 810/2014 of 25 July 2014 L 221 1 25.7.2014 ►M9 Council Regulation (EU) No 811/2014 of 25 July 2014 L 221 11 25.7.2014 ►M10 Council Implementing Regulation (EU) No 826/2014 of 30 July 2014 L 226 16 30.7.2014 ►M11 Council -

Situation in Der Ukraine 2018-12-21

Federal Department of Economic Affairs, Education and Research EAER State Secretariat for Economic Affairs SECO Bilateral Economic Relations Sanctions Version of 21.12.2018 Sanctions program: Situation in der Ukraine: Verordnung vom 27. August 2014 über Massnahmen zur Vermeidung der Umgehung internationaler Sanktionen im Zusammenhang mit der Situation in der Ukraine (SR 946.231.176.72), Anhänge 2, 3 und 4 Origin: EU Sanctions: Art. 8 (Verbot der Eröffnung neuer Geschäftsbeziehungen) Sanctions program: Situation en Ukraine: Ordonnance du 27 août 2014 instituant des mesures visant à empêcher le contournement de sanctions internationales en lien avec la situation en Ukraine (RS 946.231.176.72), annexes 2, 3 et 4 Origin: EU Sanctions: art. 8 (Interdiction de nouer de nouvelles relations d’affaires) Sanctions program: Situazione in Ucraina: Ordinanza del 27 agosto 2014 che istituisce provvedimenti per impedire l’aggiramento delle sanzioni internazionali in relazione alla situazione in Ucraina (RS 946.231.176.72), allegati 2, 3 e 4 Origin: EU Sanctions: art. 8 (Divieto di apertura di nuove relazioni d’affari) Individuals SSID: 175-39832 Name: Pozdnyakova Olga Valerievna Spelling variant: a) Pozdnyakova Olga Valeryevna (Russian) b) ПОЗДНЯКОВА Ольга Валерьевна (Russian) c) Pozdnyakova Olga Valeriyivna (Ukrainian) d) ПОЗДНЯКОВА Ольга Валеріївна (Ukrainian) DOB: 30 Mar 1982 POB: Shakhty, Rostov Oblast, Russian Federation Justification: “Chairperson” of the “Central Electoral Commission” of the so-called “Donetsk People's Republic”. In this capacity, she participated in the organisation of the so-called “elections” of 11 Nov 2018 in the so-called “Donetsk People's Republic”, and thereby actively supported and implemented actions and policies which undermine the territorial integrity, sovereignty and independence of Ukraine, and further destabilised Ukraine.