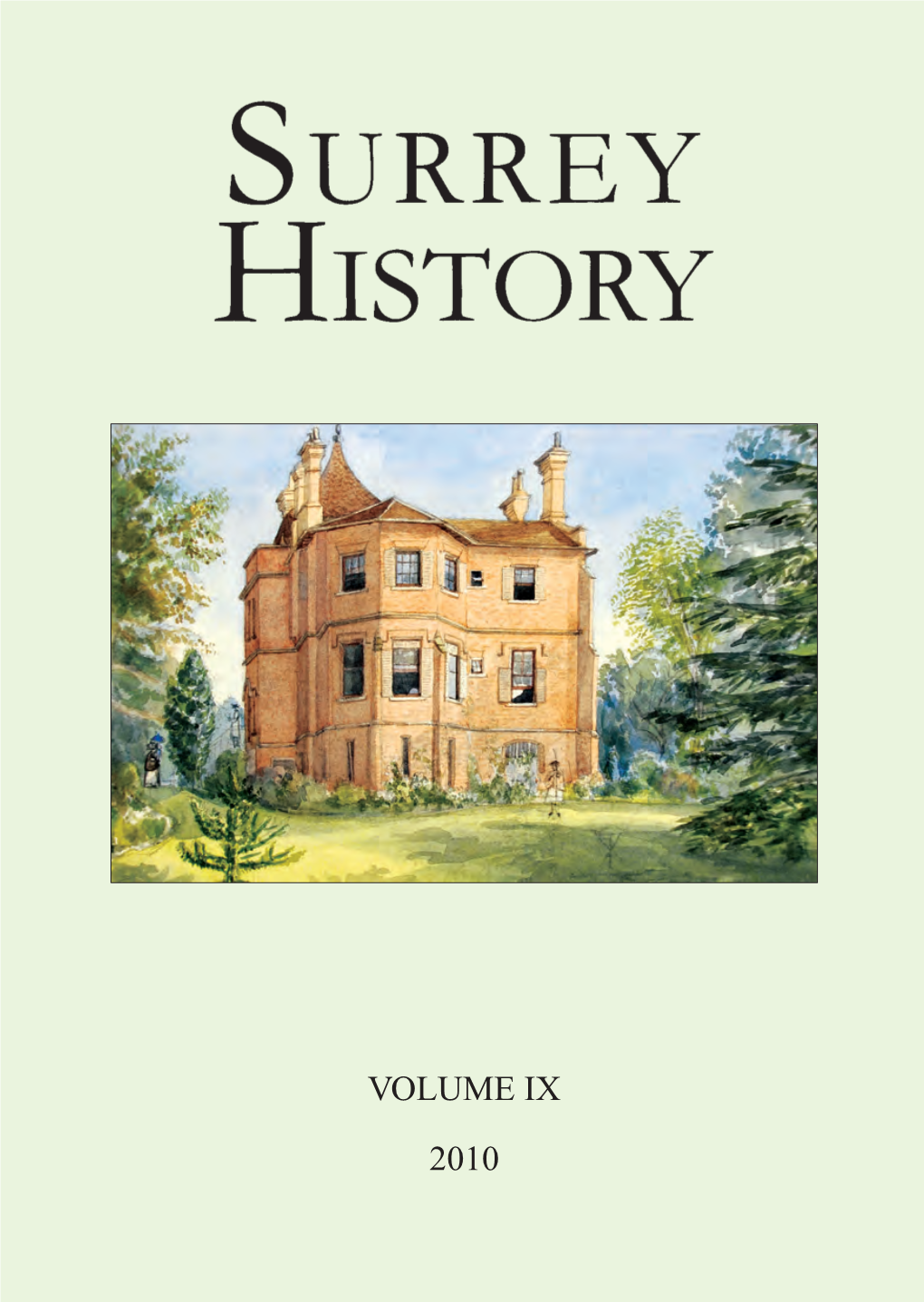

Surrey History IX 2010

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Invisible Man-Exhibition-Advisory-6.20.19.Pdf

Image captions on page 3 The Los Angeles County Museum of Art (LACMA) presents The Invisible Man and the Masque of Blackness, marking the artist Zak Ové’s first solo exhibition in Los Angeles. Ové (b. 1966) is a British visual artist of Trinidadian descent who works in sculpture, film, and photography. His 40-piece sculptural installation The Invisible Man and the Masque of Blackness features a group of identical, 6 1/2-foot-tall reproductions of an African figure that the artist received as a gift from his father in his early childhood. Ové’s figures, fabricated from resin and graphite, hold their hands up at shoulder level in an act of quiet strength and resilience, and are spaced evenly in rows to ironically recall the formation of either a group soldiers or political dissidents. The exhibition title references two milestones in black history: Ben Jonson’s 1605 play The Masque of Blackness, the first stage production to utilize blackface makeup, and Ralph Ellison’s 1952 novel Invisible Man, the first novel by an African American to win the National Book Award. In addition to literary references, the artist draws inspiration from Caribbean Carnival, a festival that originated in the Mardi Gras celebrations of the region’s French colonists, and Canboulay, a parallel celebration in which enslaved people expressed themselves through music and costume and paid homage to their African traditions. Overall, the sculpture encapsulates the complex history of racial objectification and the evolution of black subjectivity. LACMA’s presentation will be the first time The Invisible Man and the Masque of Blackness is installed at an encyclopedic institution. -

K11 Art Foundation and New Museum Co-Present After Us

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE January 17, 2017 K11 Art Foundation and New Museum co-present After us A group exhibition of Chinese and international artists exploring how the use of online personae relates to notions of being human K11 art museum, Shanghai 17 March – 31 May 2017 CHEN Zhou, Life Imitation, 2016, Video file, 1:22 min, Image courtesy of the artist The K11 Art Foundation (KAF) is pleased to present After us, their first major project in China in partnership with the New Museum, New York. Exhibition curator Lauren Cornell, New Museum Curator and Associate Director of Technology Initiatives, is supported by Chinese curator Baoyang Chen, appointed by KAF as Assistant Curator, to explore how Chinese and international artists use surrogates, proxies, and avatars to expand the notion of being human. The exhibition features an international group of artists while focusing on emerging artists from China, in line with KAF’s mission. Included in the exhibition are works in sculpture, installation, photography, performance and video as well as works engaged with augmented and virtual reality. After us looks at the original personae that artists are animating: ones that amplify current social and emotional conditions and speculate on potential future states. With the rise of artificial intelligence, the social web and gaming, the process of adopting newly invented personae is now a common part of popular culture and daily life. Stand-ins for the self, for feelings and products, and for values and beliefs have expanded our lives and sense of possibility. The title After us raises the spectre of a society that will replace our own, and yet, many of the featured artists instead layer virtual or imagined states onto the present. -

Cultural Property, Museums, and the Pacific: Reframing the Debates Haidy Geismar*

International Journal of Cultural Property (2008) 15:109–122. Printed in the USA. Copyright © 2008 International Cultural Property Society doi:10.1017/S0940739108080089 Cultural Property, Museums, and the Pacific: Reframing the Debates Haidy Geismar* The following short articles were presented at a special session of the Pacific Arts Association, held at the College Arts Association annual meeting in New York in February 2007. Entitled “Cultural Properties—Reconnecting Pacific Arts,”the panel brought together curators and anthropologists working in the Pacific, and with Pacific collections elsewhere, with the intention of presenting a series of case stud- ies evoking the discourse around cultural property that has emerged within this institutional, social, and material framework. The panel was conceived in direct response to the ways that cultural property, specifically in relation to museum col- lections, has been discussed recently in major metropolitan art museums such as the British Museum and the Metropolitan Museum of Art (the Met). This pre- vailing cultural property discourse tends to use antiquities—that most ancient, valu- able, and malleable of material culture, defined categorically by the very distancing of time that in turn becomes a primary justification for their circulation on the market or the covetous evocation of national identity—as a baseline for discus- sion of broader issues around national patrimony and ownership. Despite the attempts of many activist groups in Canada, the United States, Aus- tralia, New Zealand, and elsewhere, indigenous cultural property in this international context is generally conceived as raising a different set of problems. In these articles the authors argue that some ethical and legal perspectives raised within the domain of indigenous cultural property discourse and practice might be relevant and use- ful to more generic discussions of cultural property. -

The Corcoran Gallery of Art My Initial Thoughts on the Exhibition

The Corcoran Gallery of Art My initial thoughts on the exhibition philosophy of the Gallery are as follows: The Corcoran has five major attributes. 1. The permanent collection . " 2. Washington artists 3. The School 4. Location 5. Gallery space 1. Permanent Collection The permanent collection is the finest collection of 18th and 19th Century American art. The Clark Collection has invaluable European masterpieces. In addition, the Corcoran hae prints, drawings and recent acquisitions of contemporary art. The entire permanent collection should be re-examined and more fully utilized. In fact, a NEA Grant exists for the utilization of the permanent collection. Work must be done on this project immediately. My thoughts on the Corcoran are than certain galleries should be used to "lead into" the collection. In the lower atrium, galleries 41 and 42 could be used by drawings and prints from the permanent collection. In the upper atrium, galleries 65 , 66 and 68 could be used for exhibiting of modern paintings and recent acquisitions in the permanent collection. All these galleries could be made available on special occasions. The permanent collection would commence in gallery 76 and move logically around into galleries 65 through 68. For temporary exhibitions galleries 62, 63, 64 and 67 are magnificant huge spaces. Gallery 58 should come into operation as a gallery space. In the lower atrium, gallery 30 and possibly 42 should be used for Washington art. The corridors and atrium space gives further opportunity for the exhibition of work. Consideration should be given to the exhibition of the entire permanent collection, if that is possible. -

Download Our Exhibition Catalogue

FOREWORD Published to accompany the exhibition at We are delighted to welcome you to the second exhibition at Two Temple Place, London 26th January 2013 – 14th April 2013 Two Temple Place, Amongst Heroes: the artist in working Cornwall. Published in 2013 by Two Temple Place 2 Temple Place, London, wc2r 3bd The Bulldog Trust launched its Exhibition Programme at our Copyright © Two Temple Place headquarters on the Embankment in 2011. In welcoming the public to Two Temple Place we have three objectives: to raise Raising the Worker: awareness of museums and galleries around the UK by displaying Cornwall’s Artists and the Representation of Industry Copyright © Roo Gunzi part of their collections; to promote curatorial excellence by offering up-and-coming curators the opportunity to design a What are the Cornish boys to do? How Changing Industry Affected Cornwall’s Population high profile solo show with guidance from our experienced Copyright © Dr Bernard Deacon curatorial advisor; and to give the public the opportunity to Trustee of the Royal Institution of Cornwall and Honorary Research Fellow, University of Exeter visit and enjoy Two Temple Place itself. A catalogue record for this publication is available from the British Library Two Temple Place was originally built as an office for William Waldorf Astor in the late 19th century and the Bulldog Trust isbn 978-0-9570628-1-8 have been fortunate to own the house since 1999. For our curators, Designed and produced by NA Creative devising a show for the ornate and intricately decorated space is a huge challenge that calls for imagination and ingenuity. -

Victorians Decoded: Art and Telegraphy

Victorians Decoded: Art and Telegraphy - New Exhibition Celebrates 150th Anniversary of the Transatlantic Cable Submitted by: Rose Media Group Wednesday, 10 August 2016 Wednesday, 10th August 2016 Guildhall Art Gallery, City of London, 20th September 2016 to 22nd January 2017 The 150th anniversary of the first communications cable laid across the Atlantic Ocean, connecting Europe with America will be celebrated in a new and free exhibition entitled ‘Victorians Decoded: Art and Telegraphy’ (http://www.cityoflondon.gov.uk/things-to-do/visit-the-city/attractions/guildhall-galleries/Pages/victorians-decoded.aspx) at the City of London Corporation’s Guildhall Art Gallery, from 20th September 2016 to 22nd January 2017. This exciting collaboration between Guildhall Art Gallery, King’s College London, The Courtauld Institute of Art and the Institute of Making at University College London will explore how cable telegraphy transformed people’s understanding of time, space and speed of communication. Never-before-seen paintings from the City Corporation’s art gallery and work by prominent Victorian artists will be on display as well as rare artefacts such as code books, communication devices, samples of transatlantic telegraph cables and ‘The Great Grammatizor’, a specially-designed messaging machine that will enable the public to create a coded message of their own. Paintings by Edward John Poynter, Edwin Landseer, James Clarke Hook, William Logsdail, William Lionel Wyllie and James Tissot will be displayed, all of whom registered a changing world. Four themed rooms; Distance, Resistance, Transmission and Coding will tell the story of laying the heavy cables which weighed more than one imperial ton per kilometre across the Atlantic Ocean floor, from Valentia Island in Ireland to Newfoundland in Canada. -

Theaster Gates and Michelle Grabner to Curate Sculpture Milwaukee's

Press Contact: Meg Strobel FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE Director of Marketing & Community Engagement Sculpture Milwaukee (920)427-0900 [email protected] THEASTER GATES AND MICHELLE GRABNER TO CURATE SCULPTURE MILWAUKEE’S 2021 EXHIBITION [MILWAUKEE, WI, February 16, 2021—] Sculpture Milwaukee announced today that its 2021 exhibition will be co-curated by artists Theaster Gates and Michelle Grabner. The show will launch in June 2021 and run through autumn of 2022. Now in its fifth year, Sculpture Milwaukee is one of the largest annual outdoor exhibitions to focus on contemporary sculpture and public art practices. The announcement of Gates and Grabner as co-curators continues the Guest Curator Program which began last year with Mary Jane Jacob, Professor and Director of the Institute for Curatorial Research and Practice, School of the Art Institute of Chicago, and Lisa Sutcliffe, the Herzfeld Curator of Photography and Media Arts at the Milwaukee Art Museum. Their contributions expanded the structure of the exhibition by introducing a technoscape film by Leslie Hewitt and a video by Amy Yoes into the structure of the exhibition. “We’re excited about the new ways in which Gates and Grabner will shape the exhibition,” said Sculpture Milwaukee's Board Chair, Wayne Morgan of Baker Tilly. Adding, “Theaster Gates, and Michelle Grabner are two influential artists and educators who make their home in the American Midwest where they have dedicated themselves to supporting artists and the artistic imagination in local, regional, and national -

Walker Art Center Exhibition Chronology Living Minnesota

Walker Art Center Exhibition Chronology Title Opening date Closing date Living Minnesota Artists 7/15/1938 8/31/1938 Stanford Fenelle 1/1/1940 ?/?/1940 Grandma’s Dolls 1/1/1940 ?/?/1940 Parallels in Art 1/4/1940 ?/?/1940 Trends in Contemporary Painting 1/4/1940 ?/?/1940 Time-Off 1/4/1940 1/1/1940 Ways to Art: toward an intelligent understanding 1/4/1940 ?/?/1940 Letters, Words and Books 2/28/1940 4/25/1940 Elof Wedin 3/1/1940 ?/?/1940 Frontiers of American Art 3/16/1940 4/16/1940 Artistry in Glass from Dynastic Egypt to the Twentieth Century 3/27/1940 6/2/1940 Syd Fossum 4/9/1940 5/12/1940 Answers to Questions 5/8/1940 7/1/1940 Edwin Holm 5/14/1940 6/18/1940 Josephine Lutz 6/1/1940 ?/?/1940 Exhibition of Student Work 6/1/1940 ?/?/1940 Käthe Kollwitz 6/1/1940 ?/?/1940 Walker Art Center Exhibition Chronology Title Opening date Closing date Paintings by Greek Children 6/1/1940 ?/?/1940 Jewelry from 1940 B.C. to 1940 A.D. 6/27/1940 7/15/1940 Cameron Booth 7/1/1940 ?/?/1940 George Constant 7/1/1940 7/30/1940 Robert Brown 7/1/1940 ?/?/1940 Portraits of Indians and their Arts 7/15/1940 8/15/1940 Mac Le Sueur 9/1/1940 ?/?/1940 Paintings and their X-Rays 9/1/1940 10/15/1940 Paintings by Vincent Van Gogh 9/24/1940 10/14/1940 Walter Kuhlman 10/1/1940 ?/?/1940 Marsden Hartley 11/1/1940 11/30/1940 Clara Mairs 11/1/1940 ?/?/1940 Meet the Artist 11/1/1940 ?/?/1940 Unpopular Art 11/7/1940 12/29/1940 National Art Week 11/25/1940 12/5/1940 Art of the Nation 12/1/1940 12/31/1940 Anne Wright 1/1/1941 ?/?/1941 Walker Art Center Exhibition Chronology Title -

EXHIBITION Advisory

^ EXHIBITION Advisory Exhibition: Julie Mehretu On View: November 3, 2019–September 7, 2020 (BCAM, Level 1 and 3) Image captions on page 6 (Los Angeles—September 16, 2019) The Los Angeles County Museum of Art (LACMA) presents Julie Mehretu, a mid-career survey co-organized with the Whitney Museum of American Art. The exhibition unites nearly 40 works on paper with 35 paintings dating from 1996 to the present by Julie Mehretu (b. 1970, Addis Ababa, Ethiopia), along with a print by Rembrandt and a film on Mehretu by the artist Tacita Dean. The first-ever comprehensive survey of Mehretu’s career, the exhibition covers over two decades of her artistic evolution, revealing her early focus on drawing, mapping, and iconography and her more recent introduction of bold gestures, sweeps of saturated color, and figurative elements. Mehretu’s examination of the histories of art, architecture, and past civilizations intermingle with her interrogations into themes of migration, revolution, climate change, global capitalism, and technology in the contemporary moment. Her play with scale, as evident in her intimate drawings and large canvases and complex techniques in printmaking, will be explored in depth. Julie Mehretu is curated by Christine Y. Kim, curator of contemporary art at LACMA, with Rujeko Hockley, assistant curator at the Whitney Museum of American Art. Following its presentation at LACMA, the exhibition will travel to the High Museum of Art, Atlanta, GA (October 24, 2020–January 31, 2021); the Whitney Museum of American Art, New York, NY (March 19–August 8, 2021); and the Walker Art Center, Minneapolis, MN (October 16, 2021–March 6, 2022). -

List of Exhibitions Held at the Corcoran Gallery of Art from 1897 to 2014

National Gallery of Art, Washington February 14, 2018 Corcoran Gallery of Art Exhibition List 1897 – 2014 The National Gallery of Art assumed stewardship of a world-renowned collection of paintings, sculpture, decorative arts, prints, drawings, and photographs with the closing of the Corcoran Gallery of Art in late 2014. Many works from the Corcoran’s collection featured prominently in exhibitions held at that museum over its long history. To facilitate research on those and other objects included in Corcoran exhibitions, following is a list of all special exhibitions held at the Corcoran from 1897 until its closing in 2014. Exhibitions for which a catalog was produced are noted. Many catalogs may be found in the National Gallery of Art Library (nga.gov/research/library.html), the libraries at the George Washington University (library.gwu.edu/), or in the Corcoran Archives, now housed at the George Washington University (library.gwu.edu/scrc/corcoran-archives). Other materials documenting many of these exhibitions are also housed in the Corcoran Archives. Exhibition of Tapestries Belonging to Mr. Charles M. Ffoulke, of Washington, DC December 14, 1897 A catalog of the exhibition was produced. AIA Loan Exhibition April 11–28, 1898 A catalog of the exhibition was produced. Annual Exhibition of the Work by the Students of the Corcoran School of Art May 31–June 5, 1899 Exhibition of Paintings by the Artists of Washington, Held under the Auspices of a Committee of Ladies, of Which Mrs. John B. Henderson Was Chairman May 4–21, 1900 Annual Exhibition of the Work by the Students of the CorCoran SChool of Art May 30–June 4, 1900 Fifth Annual Exhibition of the Washington Water Color Club November 12–December 6, 1900 A catalog of the exhibition was produced. -

Curate Your Own Exhibition

Curate your own exhibition Secondary: (ages 11 – 14) Visual arts Students curate an exhibition on a theme of interest to them. The exhibition includes work by six artists, one of which is the student themselves. Students design the gallery collection, research artists working on similar ideas, and write statements describing the collection and each work within it. Ultimately, students connect the visual art world to their personal vision for an exhibition. Time allocation About 6 lesson periods Subject content Explore cultural and artistic context, traditions and art history Understand and appreciate the role of a curator Interpret ideas and reasoning behind artwork Develop technical skill in medium of their choice Creativity and This unit has a creativity and critical thinking focus: critical thinking Make connections between concepts in different artworks Generate unique ideas and create artworks that fit a theme Justify and reflect on expressive choices as a curator Other skills Communication Key words art history; curation; exhibition; inquiry; galleries Products and processes to assess Students demonstrate creativity by generating their own vision for an original engaging exhibition, selecting appropriate works, and creating their own piece of creative work to fit the theme. They justify their choices in discussions and presentations and articulate the reasoning behind the creation and inclusion of images in clear written statements. At the highest levels of achievement, they offer original, richly expressed, balanced, and appropriate explanations and demonstrate that they have carefully considered how art can be interpreted, and how artists work with concepts and themes. Author: Jillian Hogan/Boston College (United States). This work was developed for the OECD for the CERI project Fostering and assessing creativity and critical thinking skills. -

A Catalogue of the Collection of American Paintings in the Corcoran Gallery of Art

This page intentionally left blank This page intentionally left blank A Catalogue of the Collection of American Paintings in The Corcoran Gallery of Art Volume 2 Painters born from 1850 to 1910 This page intentionally left blank A Catalogue of the Collection of American Paintings in The Corcoran Gallery of Art Volume 2 Painters born from 1850 to 1910 by Dorothy W. Phillips Curator of Collections The Corcoran Gallery of Art, Washington D.G. 1973 Library of Congress Catalogue Card Number N 850. A 617 Designed by Graham Johnson/Lund Humphries Printed in Great Britain by Lund Humphries Contents Foreword by Roy Slade, Director vi Introduction by Hermann Warner Williams, Jr., Director Emeritus vii Acknowledgments ix Notes on the Catalogue x Catalogue i Index of titles and artists 199 This page intentionally left blank Foreword As Director of the Corcoran Gallery of Art, I am pleased that Volume II of the Catalogue of the American Paintings in the Corcoran Gallery of Art, which has been in preparation for some five years, has come to fruition in my tenure. The second volume deals with the paintings of artists born between 1850 and 1910. The documented catalogue of the Corcoran's American paintings carries forward the project, initiated by former Director Hermann Warner Williams, Jr., of providing a series of defini• tive publications of the Gallery's considerable collection of American art. The Gallery intends to continue with other volumes devoted to contemporary American painting, sculpture, drawings, watercolors and prints. In recent years the growing interest in and concern for American paint• ing has become apparent.