Damage to Records in Darwin Caused by Cyclone Tracy

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

In the Aftermath of Cyclone Yasi: AIR Damage Survey Observations

AIRCURRENTS By IN THE AFTERMATH OF CYCLONE YaSI: AIR DAMAGE SURVEY OBSERVATIONS EDITOR’S NOTE: In the days following Yasi’s landfall, AIR’s post-disaster survey team visited areas in Queensland affected by the storm. This article 03.2011 presents their findings. By Dr. Kyle Butler and Dr. Vineet Jain Edited by Virginia Foley INTRODUCTION Severe Cyclone Yasi began as a westward-moving depression In addition to the intense winds, Yasi brought 200-300 off Fiji that rapidly developed into a tropical storm before millimeters of precipitation in a 24 hour period and a storm dawn on January 30, 2011. Hours later, Yasi blew across the surge as high as five meters near Mission Beach. northern islands of Vanuatu, continuing to grow in intensity and size and prompting the evacuation of more than 30,000 residents in Queensland, Australia. By February 2 (local time), the storm had achieved Category 5 status on the Australian cyclone scale (a strong Category 4 on the Saffir-Simpson scale). At its greatest extent, the storm spanned 650 kilometers. By the next day, it became clear that Yasi would spare central Queensland, which had been devastated by heavy flooding in December. But there was little else in the way of good news. Yasi made landfall on the northeast coast of Queensland on February 3 between Innisfail and Cardwell with recorded gusts of 185 km/h. Satellite-derived sustained Figure 1. Satellite-derived 10-minute sustained wind speeds in knots just after wind speeds of 200 km/h were estimated near the center Cyclone Yasi made landfall. -

Cyclone Tracey-Key Findings.Pdf

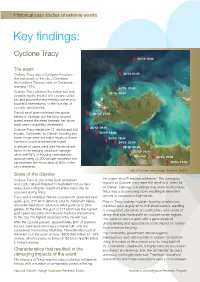

Historical case studies of extreme events Key findings: Cyclone Tracy 22/12-15:30 The event Cyclone Tracy was a Category 4 cyclone 22/12-21:00 that laid waste to the city of Darwin in the Northern Territory early on Christmas morning 1974. 23/12- 01:30 Cyclone Tracy showed the nation just how 23/12- 09:00 devastating the impact of a cyclone could be, and awoke the engineering community, local and international, to the true risk of cyclonic wind storms. Tracy’s small size minimised the spatial 23/12- 21:00 extent of damage, but her slow forward speed meant the areas beneath her storm track were completely devastated. 24/12- 09:00 Cyclone Tracy resulted in 71 deaths and 650 injuries. Fortunately for Darwin, flooding and 24/12- 13:00 storm surge were not major issues or these 24/12- 18:30 numbers could have been far higher. 24/12- 21:00 In almost all cases wind was the dominant 25/12- 00:30 factor in the ensuing structural damage, 25/12- 03:00 which left 94% of housing uninhabitable, Darwin approximately 40,000 people homeless and 25/12- 09:00 necessitated the evacuation of 80% of the 25/12- 12:00 city’s residents. Path of Cyclone Tracy. Image: Matthew Mason Scale of the disaster Cyclone Tracy is one of the most prominent the region since European settlement. The damaging and costly natural disasters in Australia’s history. Very impacts of Cyclone Tracy were the result of a ‘direct hit’ rarely does a disaster impact an entire major city, as on Darwin. -

Cyclone Tracy Report 1975

DEPARTMENT OF HOUSING AND CONSTRUCTION REPORT ON CYCLONE “TRACY” - Effect On Buildings - DECEMBER 1974 Volume 1 BY GEORGE R WALKER SENIOR LECTURER DEPARTMENT OF ENGINEERING JAMES COOK UNIVERSITY OF NORTH QUEENSLAND MARCH 1975 CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS INTRODUCTION Chapter 1 SUMMARY Chapter 2 CHARACTERISTICS OF CYCLONE “TRACY” Chapter 3 GENERAL PATTERN OF DAMAGE Chapter 4 STRUCTURAL BEHAVIOUR Chapter 5 IMPLICATIONS OF DISASTER Chapter 6 BIBLIOGRAPHY 2 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS In assembling this report the writer was helped by many people to whom he is deeply grateful. The writer would like to particularly acknowledge the support of Professor D. H. Trollope, Pro-Vice-Chancellor and Professor of Civil Engineering at the James Cook University of North Queensland whose initiative and encouragement in the development of tropical cyclone studies at this University following cyclone “Althea” in December, 1971, has been a primary factor in the writer’s own involvement in this work. The ready and willing co-operation of the Director of the Department of Housing and Construction in Darwin, Mr G. Redmond, and his staff, in particular the Principal Structural Engineer, Mr J. Gamble, is gratefully acknowledged. Much assistance was also gained from members of the Department’s Darwin Reconstruction Study Group. The willing co- operation of Mr D. Green of the Northern Territory Housing Commission was also appreciated. A great deal of assistance was gained in the actual investigation of the damage from others similarly engaged. In particular the writer would like to express his thanks for the assistance of Mr K. Baker and Mr Nicholls and other members of staff of Halpern Glick Pty. -

The Age Natural Disaster Posters

The Age Natural Disaster Posters Wild Weather Student Activities Wild Weather 1. Search for an image on the Internet showing damage caused by either cyclone Yasi or cyclone Tracy and insert it in your work. Using this image, complete the Thinking Routine: See—Think— Wonder using the table below. What do you see? What do you think about? What does it make you wonder? 2. World faces growing wild weather threat a. How many people have lost their lives from weather and climate-related events in the last 60 years? b. What is the NatCatService? c. What does the NatCatService show over the past 30 years? d. What is the IDMC? e. Create a line graph to show the number of people forced from their homes because of sudden, natural disasters. f. According to experts why are these disasters getting worse? g. As human impact on the environment grows, what effect will this have on the weather? h. Between 1991 and 2005 which regions of the world were most affected by natural disasters? i. Historically, what has been the worst of Australia’s natural disasters? 3. Go to http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Global_tropical_cyclone_tracks-edit2.jpg and copy the world map of tropical cyclones into your work. Use the PQE approach to describe the spatial distribution of world tropical cyclones. This is as follows: a. P – describe the general pattern shown on the map. b. Q – use appropriate examples and statistics to quantify the pattern. c. E – identifying any exceptions to the general pattern. 4. Some of the worst Question starts a. -

Knowing Maintenance Vulnerabilities to Enhance Building Resilience

Knowing maintenance vulnerabilities to enhance building resilience Lam Pham & Ekambaram Palaneeswaran Swinburne University of Technology, Australia Rodney Stewart Griffith University, Australia 7th International Conference on Building Resilience: Using scientific knowledge to inform policy and practice in disaster risk reduction (ICBR2017) Bangkok, Thailand, 27-29 November 2017 1 Resilient buildings: Informing maintenance for long-term sustainability SBEnrc Project 1.53 2 Project participants Chair: Graeme Newton Research team Swinburne University of Technology Griffith University Industry partners BGC Residential Queensland Dept. of Housing and Public Works Western Australia Government (various depts.) NSW Land and Housing Corporation An overview • Project 1.53 – Resilient Buildings is about what we can do to improve resilience of buildings under extreme events • Extreme events are limited to high winds, flash floods and bushfires • Buildings are limited to state-owned assets (residential and non-residential) • Purpose of project: develop recommendations to assist the departments with policy formulation • Research methods include: – Focused literature review and benchmarking studies – Brainstorming meetings and research workshops with research team & industry partners – e.g. to receive suggestions and feedbacks from what we have done so far Australia – in general • 6th largest country (7617930 Sq. KM) – 34218 KM coast line – 6 states • Population: 25 million (approx.) – 6th highest per capita GDP – 2nd highest HCD index – 9th largest -

Tropical Cyclone Larry – Damage to Buildings in Innisfail Area Executive Summary

CYCLONE TESTING STATION Tropical Cyclone Larry Damage to buildings in the Innisfail area Report: TR51 September, 2006 Cyclone Testing Station School of Engineering James Cook University Queensland, 4811 Phone: 07 4781 4340 Fax: 07 4775 1184 Front Cover Satellite Image Sourced from the Bureau of Meteorology <www.bom.gov.au> CYCLONE TESTING STATION SCHOOL of ENGINEERING JAMES COOK UNIVERSITY TECHNICAL REPORT NO. 51 Tropical Cyclone Larry Damage to buildings in the Innisfail area September 2006 Authors: D. Henderson1, J. Ginger1, C. Leitch1, G. Boughton2, and D. Falck2 1 Cyclone Testing Station, James Cook University, Townsville 2 TimberED Services, Perth © Cyclone Testing Station, James Cook University Henderson, D. J. (David James), 1967-. Tropical Cyclone Larry – Damage to buildings in the Innisfail area Bibliography. ISBN 0 86443 776 5 ISSN 0158-8338 1. Cyclone Larry 2006 2. Buildings – Natural disaster effects 3. Wind damage I. Ginger, John David (1959-) II. Leitch, Campbell (1952-) III Boughton, Geoffrey Neville (1954-) IV Falck, Debbie Joyce (1961-) V James Cook University. Cyclone Testing Station. VI. Title. (Series : Technical Report (James Cook University. Cyclone Testing Station); no. 51). LIMITATIONS OF THE REPORT The Cyclone Testing Station (CTS) has taken all reasonable steps and due care to ensure that the information contained herein is correct at the time of publication. CTS expressly exclude all liability for loss, damage or other consequences that may result from the application of this report. This report may not be published except in full unless publication of an abstract includes a statement directing the reader to the full report. Cyclone Testing Station Report TR51 Tropical Cyclone Larry – Damage to Buildings in Innisfail area Executive Summary Tropical Cyclone Larry made landfall on 20th March 2006 near the town of Innisfail and caused damage to a number of buildings in Innisfail and the surrounding district. -

Civil Society Mobilisation After Cyclone Tracy, Darwin 1974

Environmental Hazards ISSN: (Print) (Online) Journal homepage: https://www.tandfonline.com/loi/tenh20 Civil society mobilisation after Cyclone Tracy, Darwin 1974 John Handmer & Pascale Maynard To cite this article: John Handmer & Pascale Maynard (2020): Civil society mobilisation after Cyclone Tracy, Darwin 1974, Environmental Hazards, DOI: 10.1080/17477891.2020.1838254 To link to this article: https://doi.org/10.1080/17477891.2020.1838254 View supplementary material Published online: 12 Nov 2020. Submit your article to this journal Article views: 6 View related articles View Crossmark data Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at https://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=tenh20 ENVIRONMENTAL HAZARDS https://doi.org/10.1080/17477891.2020.1838254 Civil society mobilisation after Cyclone Tracy, Darwin 1974 John Handmera,b and Pascale Maynardb aInternational Institute for Applied Systems Analysis (IIASA), Vienna, Austria; bSchool of Science, RMIT University, Melbourne, Australia ABSTRACT ARTICLE HISTORY Major disasters challenge or exceed the capacity of the official Received 20 July 2020 emergency management sector to provide needed rescue Accepted 6 October 2020 services, support and relief. Emergency services in most KEYWORDS jurisdictions do not have the surge capacity for unusual or Cyclone Tracy; Darwin, extreme events without drawing on other jurisdictions or local spontaneous volunteers; civil people from outside the formal emergency management society mobilisation; surge organisations. In such circumstances, those in the affected area capacity need to organise themselves and make maximum use of local resources to cope with the immediate aftermath of impact. To find the required surge capacity, this suggests a whole of society response with the official system working with the capacities of people, commerce and organisations outside the emergency sector. -

Scott, Terry 0.Pdf

62015.001.001.0288 INSURANCE THEIVES We own an investment property in Karratha and are sick and tired of being ripped off by scheming insurance companies. There has to be an investigation into colluding insurance companies and how they are ripping off home owners in the Pilbara? Every year our premium escalates, in the past 5 years our premium has increased 10 fold even though the value of our property is less than a third of its value 5 years ago. Come policy renewal date I ring around for quotes and look online only to be told that these insurance companies have to increase their premiums because of the many natural disasters on the eastern seaboard, ie; the recent devastating cyclones and floods like earlier this year or the regular furphy, the cost of rebuilding in the Northwest. Someone needs to tell these thieves that the boom is over in the Pilbara and home owners there should no longer be bailing out insurance companies who obviously collude in order to ask these outrageous premiums. I decided to do a bit of research and get some facts together and approach the federal and local member for Karratha and see what sort of reply I would get. But the more I looked into what insurance companies pay out for natural disasters the more confused I became because the sums just don’t add up! Firstly I thought I would get a quote for a property online with exactly the same specifications as ours in Karratha but in Innisfail, Queensland. This was ground zero, where over the past few years’ cyclones have flattened most of this township. -

Cyclone Tracy 30-Year Retrospective

Cyclone Tracy 30-Year Retrospective TM Risk Management Solutions C HARACTERISTICS Cyclone Tracy struck the city of Darwin on the northern coast of Australia early Christmas Day, 1974, causing immense devastation. Small and intense, Tracy’s recorded winds reached 217 km/hr (134 mph; strong category 3 on the 5-point Australian Bureau of Meteorology scale) before the anemometer at Darwin city airport failed at 3:10 am, still 50 minutes before the storm’s eye passed overhead. Satellite and damage observations suggest that Tracy’s winds topped 250 km/hr (155 mph), and the storm’s strength is generally described as a category 4. It was also the smallest tropical cyclone ever recorded in either hemisphere, with gale force winds at 125 km/hr (77 mph) extending just 50 km (31 miles) from the center; the eye was only about 12 km (7.5 miles) wide when it passed over Darwin. Remarkably, Tracy’s central pressure was estimated at a somewhat average 950 mb which is unusually low given the wind strength. Tracy formed on December 20 about 700 km (435 miles) north-northeast of Darwin. It intensified rapidly and became a named storm within 24 hours. Moving south-westwards, Tracy was expected to pass well to the north of Darwin, and ABC radio famously reported that it posed no threat to Australia’s mainland on December 22. Early on December 24, however, Tracy made a sudden change in direction steering directly toward land. It passed directly over Darwin between midnight and 7:00 am the next day with a slow forward speed of around 6 km/hr (less than 4 mph). -

MANAGING TROPICAL CYCLONE RISK DOWN UNDER by Dr

OCTOBER 2012 AIRCURRENTS: MANAGING TROPICAL CYCLONE RISK DOWN UNDER by Dr. Peter Sousounis and Robert Zalisk EDITOR’S NOTE: Thousands of kilometers of Australian coastline are susceptible to tropical cyclones. Using three historical events as examples—Tracy, Wanda, and Vance—Senior Principal Scientist Dr. Peter Sousounis and Senior Writer Robert Zalisk outline the country’s costly experience with tropical cyclones and show how the AIR Tropical Cyclone Model for Australia can help manage the risk. Australia’s unique geography makes it a magnet for tropical cyclones. A quick glance at a map (see Figure 1) shows the narrow THE ARTICLE: Uses three historical tropical east-west corridor between Indonesia and Papua New Guinea to cyclones to illustrate the wind, flood, and storm the north and Australia to the south into which pass storms from surge damage Australia suffers every year from tropical both the east and the west. In just the last five decades, more storms, identifies some specifically Australian conditions and than 500 tropical cyclones have formed in and passed through this circumstances captured by the AIR Tropical Cyclone Model for region. Australia, and demonstrates the value of using model simulations to stress test portfolios. Losses in Australia from tropical cyclones can be substantial and result from a combination of three storm-related hazards: wind, HIGHLIGHTS: AIR estimates that the occurrence of a storm similar storm surge, and precipitation-induced flooding. Severe Tropical to 2011’s Cyclone Yasi farther south, near Brisbane, would cost Cyclone Tracy1 in 1974, for example, caused nearly AUD 5 billion the insurance industry nearly AUD 4.3 billion. -

Report on Cyclone Tracy December 1974

INTRODUCTION The aim of this report is to present the results of investigation that have taken place since the preparation of the interim report (Australian Bureau of Meteorology 1975) and to incorporate wherever possible the findings of the initial report. Several investigations of various facets of Tracy by a number of organisations have highlighted uncertainties in defining basic parameters, particularly the wind field. New data and more refined techniques have enabled these parameters to be specified with greater confidence. The new data included higher quality satellite photographs, additional radar information, and the results of further aerial and ground surveys. Careful consistency checks have been undertaken. Also of particular assistance have been readings of a atmospheric pressure and rainfall taken by Bureau staff at Darwin airport during the passage of the eye. These readings were temporarily lost in the immediate aftermath of the cyclone. The eye of the storm passed directly over Darwin, where a major meteorological installation was located. This provided a rare opportunity for obtaining detailed measurements inside such a storm, particularly by radar. Unfortunately, as is often the case in the severe meteorological conditions associated with tropical cyclones, some of the instruments malfunctioned or were put out of action by power failures or the impact of flying debris. Nevertheless, considerable data have been collected and besides providing information for this report, are being used as a basis for further research. A chronology is presented at the commencement of the report to enable the reader to obtain a broad perspective of Tracy.* An examination is then made of the general synoptic background, isolating qualitatively a number of parameters considered to be important in the development of the cyclone. -

IWTCLP-4 T.0 ITS Report Leroux

Rapid changes in track, intensity, and structure at landfall Marie-Dominique Leroux, Kim Wood To cite this version: Marie-Dominique Leroux, Kim Wood. Rapid changes in track, intensity, and structure at landfall. FOURTH INTERNATIONAL WORKSHOP ON TROPICAL CYCLONE LANDFALL PROCESSES (IWTCLP-IV), World Meteorological Organization, Dec 2017, Macao, China. hal-01718304 HAL Id: hal-01718304 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-01718304 Submitted on 27 Feb 2018 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. WMO/CAS/WWW FOURTH INTERNATIONAL WORKSHOP ON TROPICAL CYCLONE LANDFALL PROCESSES Rapid changes in track, intensity, and structure at landfall Chair: Marie-Dominique Leroux Cellule Recherche Cyclones, Météo-France Direction Interrégionale pour l'Océan Indien 50 boulevard du Chaudron, 97490 Sainte-Clotilde Rapporteur: Kim Wood Department of Geosciences, Mississippi State University 108 Hilbun Hall, 355 Lee Blvd., Mississippi State, MS, USA Working Group Members: Nancy Baker (NRL-Monterey), Esperanza Cayanan (PAGASA), Difei Deng (UNSW-Canberra and IAP),