28 by 2028 Critique Final Edit

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Gateway District SPECIFIC PLAN

CITY OF SOUTH GATE Gateway District FACT SHEET SPECIFIC PLAN Upcoming Opportunities for Community CITY OF SOUTH GATE Participation South Gate’s collaboration with business and residential communities is of paramount importance to the development of the Specific Plan. The City will host three community meetings between January and Fall 2016. 1 Community Meeting 1: Project Initiation Meeting Wednesday, January 27, 2016 Gateway The focus of the initial meeting is to increase project awareness, provide interested residents and business groups information about the Specific Plan’s purpose, study goals and timeline, and to gather feedback on the TOD vision for South Gate. 2 Community Workshop 2: Project Specific Workshop Spring/Summer 2016 The second meeting will be a workshop where the information gathered from the first meeting, as well District as technical work, will be shared. Participants will provide feedback and input on preliminary land use and design scenarios, including public access and open space. Information gathered from the SPECIFIC PLAN workshop will help define the Specific Plan’s goals and policies, and will be used to develop the Public Review Draft Specific Plan. Community Meeting 3: Public Review Draft Specific Plan 3 Summer/Fall 2016 The third meeting will provide the community an opportunity to review and comment on the Public Review Draft Specific Plan. Participants will have the chance to review key components of the Specific Plan, such as site design concepts, proposed land uses, pedestrian- and transit-oriented concepts, and strategies for public access and open space. Comments will be documented and be responded to in the Final Gateway Specific Plan. -

City Council Agenda Report

CITY COUNCIL AGENDA REPORT MEETING DATE: 4/12/2021 ITEM NO: 15 TO: Mayor and Members of the City Council SUBJECT: Approval of a Letter to the Los Angeles County Metropolitan Transportation Authority in Support of Federal Funding for the West Santa Ana Branch Light Rail Project FROM: Karen Lee, Management Analyst REVIEWED AND APPROVED BY: Melissa Burke, Administrative Manager HongDao Nguyen, City Attorney William Rawlings, City Manager RECOMMENDATION: Staff recommends that the City Council authorize the Mayor to sign, and direct staff to submit, the attached letter to the Los Angeles County Metropolitan Transportation Authority. BACKGROUND: The West Santa Ana Branch (WSAB) light rail line is a substantial public works and transportation project that will have a permanent impact on the region. This project will have tremendous impact on the City as the City’s planned station location in the Downtown will be the line’s terminus. The Los Angeles County Metropolitan Transportation Authority (Metro) is overseeing this project. During the January 12, 2021 meeting of the WSAB City Manager Technical Advisory Committee, and the board meeting of the Orangeline Development Authority/Eco-Rapid Transit on January 13, 2021, Metro staff reported that it intends to lobby for federal funding for the WSAB project to help pay the estimated cost of $6.3 to $6.5 billion in 2018 dollars based on 5% design level plus the addition of project revisions. The project costs will be updated this month based on the 15% design level. 1 ANALYSIS: Metro has requested that cities along the WSAB corridor provide letters in support of the WSAB project and Metro’s efforts to pursue federal funding for this project. -

Oei Office of Extraordinary Innovation

Tab 9 INNOVATION Defining the Problem Problem: Mobility in Los Angeles County is not working Thesis: We need to do things very differently to reduce Single Occupancy Vehicle (SOV) use Proposed solutions: Set a course, accelerate projects, and try new stuff 2 “We have to have stretch goals that area realistic” 3 ROLE OF METRO STRATEGIC PLAN • Foundation that aligns all plans, programs, and services to achieve a common vision • Establishes mission, vision, and goals to be adopted by other plans (e.g. Long Range Transportation Plan, NextGen Bus Study, etc.) • Sets principles for making decisions and conducting business 4 STRATEGIC MOBILITY: SUPPLY • Increase capacity for non-SOV modes • Improve quality of existing transit system Common Interest 5 STRATEGIC MOBILITY: DEMAND • Manage demand • Pricing beyond transit fares • CongestionCommon pricingInterest • Regulate TNCs 6 “This is a really innovative idea but we can’t do it. It’s never been done before” 7 MicroTransit Pilot Can Metro increase customer satisfaction & attract new riders? > A cross between a pooled ride and a shuttle bus > Meets increasing expectation for convenience > Expands FMLM solutions > Flexible and seamless o Integrated with transit system o Serves non-linear travel On Demand | Dynamically Routed Data Driven | Corner to Corner 8 “If we improve our service more people will use it and we can’t afford that.” 9 Mobility on Demand Partner with a transportation network company to provide better and more equitable access to 3 pilot transit stations “We could have thought of that on our own.” 11 Unsolicited Proposals: Background In February 2016, Metro opened its doors to the private sector, at an Industry> Pledged our Forumcommitment. -

Coalition Politics and the Expansion of L.A.'S Transit System

Coalition Politics and the Expansion of L.A.’s Transit System By David Luberoff Los Angeles Mayor Antonio Villaraigosa (center) celebrating the passage of Measure R in November 2008 with (from left to right): Tracy Rafter, Jerry Givens, Metro Board Member Richard Katz, Matt Raymond, Metro Board Member and County Supervisor Zev Yaroslavsky, Assemblyman Mike Feuer, Denny Zane, David Fleming, and Terence O’Day. This case was written by David Luberoff, Lecturer on Sociology at Harvard University, for the project on “Transforming Urban Transport – the Role of Political Leadership,” at Harvard’s Graduate School of Design (GSD), with financing from the Volvo Research and Educational Foundations (VREF). Alan Altshuler, Distinguished Service Professor at Harvard emeritus, provided counsel and editing assistance. The author is responsible for the facts and the accuracy of the information in the case, which does not necessarily reflect the views of VREF or GSD. © 2016 The President and Fellows of Harvard College. Draft: May 2016; Do Not Quote, Cite or Distribute Without Permission. Coalition Politics and the Expansion of LA’s Transit System Page 2 Table of Contents Overview ................................................................................................................................... 1 Context: Development and Transportation in Los Angeles ...................................................... 4 Getting the MTA Back on Track .............................................................................................. 8 Creating -

S&W Levitt VRA Counsel

Proposal to the Citizens Redistricting Commission Voting Rights Act Counsel Response to Request for Information for Legal Services January 29, 2021 STRUMWASSER ~ WOOCHER LLP PROFESSOR JUSTIN LEVITT Justin Levitt Strumwasser & Woocher LLP Burns 335 10940 Wilshire Boulevard, Suite 2000 919 Albany Street Los Angeles, California 90024 Los Angeles, California 90015 (310) 576-1233 (213) 736-7417 TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. Personnel Proposed for Engagement ............................................................................................... 1 Fredric D. Woocher ............................................................................................................................. 1 Professor Justin Levitt ......................................................................................................................... 2 Michael J. Strumwasser ........................................................................................................................ 2 Andrea Sheridan Ordin ....................................................................................................................... 3 Dale K. Larson ..................................................................................................................................... 3 Salvador E. Pérez ................................................................................................................................. 4 2a. About Strumwasser & Woocher LLP .............................................................................................. -

City Council Agenda Report

CITY COUNCIL AGENDA REPORT MEETING DATE: 11/9/2020 ITEM NO: 7 TO: Mayor and Members of the City Council SUBJECT: Informational Report Regarding the 3% Local Contribution Required Under Measure M to Fund the West Santa Ana Branch Light Rail Line FROM: Karen Lee, Management Analyst REVIEWED AND APPROVED BY: Melissa Burke, Administrative Manager Christi Hogin, City Attorney William Rawlings, City Manager RECOMMENDATION: Staff recommends that the City Council receive and file the report. BACKGROUND: Los Angeles County voters approved Measure M on November 8, 2016, which implemented a permanent county-wide sales tax increase to fund projects to greatly expand the County’s public transit system, including new rail lines, roads, and related infrastructure. The Los Angeles County Metropolitan Transportation Authority (Metro) administers Measure M funds. Funding for the West Santa Ana Branch (WSAB) line is provided by Measure M. One of Measure M’s requirements is a local contribution by jurisdictions for constructing a rail project with a new station within their boundaries. The rationale for the contribution is that local jurisdictions receive a direct benefit due to the increased access to transit service that is above and beyond the project’s benefit to the County as a whole. The contribution amount is 3% of the project’s total costs at the 30% level of its final design. It is capped at this amount for local contribution purposes, even if the total project cost increases. This amount is then divided by the number of new rail stations constructed on the line. Jurisdictions located within a one-half mile area of the new station will proportionally share the costs based on each jurisdiction’s share of the area. -

1981 Caltrans Inventory of Pacific Electric Routes

1981 Inventory of PACIFIC ELECTRIC ROUTES I J..,. I ~ " HE 5428 . red by I58 ANGELES - DISTRICT 7 - PUBLIC TRANSPORTATION BRANCH rI P37 c.2 " ' archive 1981 INVENTORY OF PACIFIC ELECTRIC ROUTES • PREPARED BY CALIFORNIA DEPARTMENT OF TRANSPORTATION (CALTRANS) DISTRICT 07 PUBLIC TRANSPORTATION BRANCH FEBRUARY 1982 • TABLE OF CONTENTS PAGE I. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 1 Pacific Electric Railway Company Map 3a Inventory Map 3b II. NQR'I'HIRN AND EASTERN DISTRICTS 4 A. San Bernardino Line 6 B. Monrovia-Glendora Line 14 C. Alhambra-San Gabriel Line 19 D. Pasadena Short Line 21 E. Pasadena Oak Knoll Line 23 F. Sierra Madre Line 25 G. South Pasadena Line 27 H. North Lake Avenue Line 30 10 North Fair Oaks Avenue Line 31 J. East Colorado Street Line 32 K. Pomona-Upland Line 34 L. San Bernardino-Riverside Line 36 M. Riverside-Corona Line 41 III. WESTERN DISTRICT 45 A. Glendale-Burbank Line 47 B. Hollywood Line Segment via Hill Street 52 C. South Hollywood-Sherman Line 55 D. Subway Hollywood Line 58 i TABLE OF CONTENTS (Contd. ) -PAGE III. WESTERN DISTRICT (Conta. ) E. San Fernando valley Line 61 F. Hollywood-Venice Line 68 o. Venice Short Line 71 H. Santa Monica via Sawtelle Line 76 I. westgate Line 80 J. Santa Monica Air Line 84 K. Soldier's Home Branch Line 93 L. Redondo Beach-Del Rey Line 96 M. Inglewood Line 102 IV. SOUTHIRN DISTRICT 106 A. Long Beach Line 108 B. American Avenue-North Long Beach Line 116 c. Newport-Balboa Line 118 D. E1 Segundo Line 123 E. San Pedro via Dominguez Line 129 F. -

Metro Set to Begin Environmental Clearance Process for West Santa Ana Branch Rail Line Connecting Southeast L.A

Latest Measure R Transit Project Moving Forward Metro Set to Begin Environmental Clearance Process for West Santa Ana Branch Rail Line Connecting southeast L.A. County to the regional transit system moved one step closer to reality today when the Los Angeles County Metropolitan Transportation Authority (Metro) Board approved contracts to proceed with environmental work and community outreach for the West Santa Ana Branch Transit Corridor project to connect L.A. Union Station and Artesia via a new rail line. The Board approved contracts with Parsons Brinkerhoff, Inc. to complete the environmental clearance for the project and a contract with Arrellano Associates, LLC for community outreach. The Board also approved a funding agreement with the Gateway Cities Council of Governments to help the 13 cities along the project corridor participate in the study. The effort will be led by the Eco-Rapid Transit Joint Powers Authority, which was created to study rail transit in the corridor. The West Santa Ana Branch Transit Corridor travels through the cities of Artesia, Bell, Bellflower, Bell Gardens, Cudahy, Cerritos, Downey, Huntington Park, Lynwood, Los Angeles, Maywood, Paramount, South Gate and Vernon. During the environmental clearance phase, various rail alignments will be studied between Los Angeles Union Station and a southern terminus in Artesia. The preferred route will ultimately be approved by the Metro Board. “Connecting southeast L.A. County to the regional transit system is an important part of Metro’s broad vision for better regional mobility,” said John Fasana, Metro Board Chair and Duarte City Council Member. “But this milestone is particularly good news for the Gateway Cities communities. -

UNIVERSITY of CALIFORNIA, IRVINE 50 Years To

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA, IRVINE 50 Years to the Wilshire Subway: The Political and Social Discourse Surrounding the Development of the Purple Line Extension THESIS submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS in Urban and Regional Planning by Olivia Harris Thesis Committee: Associate Professor Douglas Houston, Chair Assistant Professor Nicholas Marantz Associate Professor Walter Nicholls 2017 © 2017 Olivia Harris Table of Contents LIST OF FIGURES ................................................................................................................................... iii LIST OF TABLES ..................................................................................................................................... iv ACKNOWLEDGMENTS ........................................................................................................................... v ABSTRACT OF THE THESIS ................................................................................................................ vi 1. Introduction ....................................................................................................................................... 1 2. Background ......................................................................................................................................... 4 2.1 Megaprojects: Overview, History, and Urban Theory ....................................................... 4 2.1.1 Overview of Mega-projects ................................................................................................................ -

![ATN]Tha Lll]L]L](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/8835/atn-tha-lll-l-l-1818835.webp)

ATN]Tha Lll]L]L

RECEIVED Item No. 2 i\W 7 Z018 of CITYOFSOUTH GATE City South Gate WFICEOFTHECITYMANAGER3bpm CITY COUNCIL ATN]ThA Lll]L]L For the Regular Meeting of August 14, 2018 Orj4ating Deartment: ftZ4’ i7’frC1t Manager Department Director Joe Perez! SUBJECT: COMMENT LETTER FOR THE WEST SANTA ANA BRANCH TRANSIT CORRIDOR PROJECT PURPOSE: To submit comments and concerns to the Los Angeles County Metropolitan Transportation Authority (Metro) regarding potential impacts related to the West Santa Ana Branch Transit Corridor Project. Metro is receiving public input until August 24, 2018, which marks the end of their formal public comment period for a revised Notice of Preparation of a Draft Environmental Impact Statement (EIS)/Environmental Impact Report (EIR). RECOMMENDED ACTION: Authorize the Mayor to execute the comment letter regarding potential impacts related to the West Santa Branch Transit Corridor Project to the Los Angeles County Metropolitan Transportation Authority prior to August 24, 2018. FISCAL IMPACT: None. ANALYSIS: Metro is evaluating a new light rail transit line that would connect downtown Los Angeles to southeast LA County, serving the cities and communities of downtown Los Angeles, unincorporated Florence-Graham community of LA County, Vernon, Huntington Park, Bell, Cudahy, South Gate, Downey, Paramount, Bellflower and Artesia. The West Santa Ana Branch (WSAB) Transit Corridor Project is a 20-mile corridor that is undergoing an Environmental Impact Statement (EIS)/Environmental Impact Report (EIR) process to prepare the corridor for light rail use. The project’s name originates from the southern portion of the route south of the Metro Green Line that follows the old Pacific Electric streetcar alignment known as the West Santa Ana Branch Corridor. -

West Santa Ana Branch Transit Corridor Study

What is the GATEWAY DISTRICT? The Gateway District encompasses approximately 59 acres located at the north-east corner of Firestone Blvd and Atlantic Ave. It is: • The future site of the planned South Gate Transit Station along the West Santa Ana Branch Corridor Transit Line. • Identified to become a dense“transit village” designed to support a high-level of pedestrian activity. • Envisioned as a visual and functional transit gateway feature for the City of South Gate. • The optimal location for future transit- oriented development (TOD) to support the future transit station. CITY OF SOUTH GATE • Currently characterized by existing light- to heavy-industrialGatewa usesy and emerging retail uses.District Conceptual Sketch of the Gateway District SPECIFIC PLAN Fostoria Street Salt Lake Avenue South Gate City Limit Fostoria Street Wilcox Avenue Los Angeles River Angeles Los Patata Street River Angeles Los South Gate City Limit Patata Street Project Area Reisner Way Reisner Way Rayo Avenue Avenue Rayo Rayo Mason Street Patata Street Rayo Avenue Wilcox Avenue Wilcox Wilcox Avenue Atlantic AvenueWilcox Firestone Place Los Angeles River y t N a PLA Firestone Boulevard May Court Firestone Place Burke Avenue Burke Avenue E Dudlext Avenue Dudlext Avenue T Vossler Avenue w Vossler Avenue GA H T e SPECIFIC Map of the Gateway District Rayo Avenue Rayo Firestone Boulevard Avenue Rayo SOU t West Santa Ana Branch OF Patata Street Y Transit Corridor a Distric Rayo Avenue CIT G Southern Avenue Project Area Potential Station Location Mason Street Salt Lake -

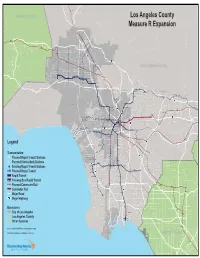

Los Angeles Equity Maps Large.Ai

S and Can yo ! Newhall n Placerita Canyon Sand C any on Ventura County ra Los Angeles County er Si Th e Ol d Measure R Expansion l el rn Bradl ey Exi Ya d t 3 xfor Ro S lk an Fe Po d Big rnan T ujung do Hubbar n a Cany yo on sn SylmarSan Fernando on Se a ga Can Moorpark un ay Canyon mp ! cl uj ch T ! Ta Ma le Gl Litt Lopez Ran enoak er xton on Pa ce s er e Port Pi Rinaldi l Cany rn age bo HWY 118 and ys K Os San Fernando Mission Br ! an Nu V Simi Valley x on Chatsworth Fo Chatsworth Wentworth eas Ar le ta Devonshire Ar Mount Gl le ! boa ta Chatsworth and e ah Bal da rn unl Ma lz rilla oodley bo S INTERSTATE W Ze per la Os el Rese 5 Plummer B Sant Plummer a Plummer Ves rra a e Manor ed Te Carlotta Lak lv Nordhoff Ar Laur l Nordhoff epu heldon ! le S on Orange S ny ta el una Ca Fo C La T INTERSTATE othill Lowel o an ! d 210 a e Orange Line Extension ot anford yo or cl n xf ose Northridge Br ani Tu Honolul enr v De S P yl ey Cir u ll Roscoe Roscoe a W Rosc ! ! oe enns ka Va ebb ent P et Gl sc rch Sun Valley enoak Fo Van Nuys re othi Ma Winn ll im a s Los Angeles County Canoga San Fernando BRT Corridors S an ! La C sh oodlake Saticoy ed i nd cle Fe lv er W ir la rnando C ne epu Naom Lank ys ey Sherman Way Sherman S Vi Verdugo ll ! Sherman Glendora Ridge Va t Sc Fo rs k ot an Nu n ott hi V k Ramp ll oo yo an Alta a Burbank/ Bob Hope Airport den Oa Vanowen enhu San Ber a t De Soto ks Canoga ! e hi yv ! Empi Can re re mp it at Fallbr ! Gl Victory Woodley el Fe Pl Ha Ta ctory enoaks ! Vi Woodm d r K Wh ! ! Victory nan enne oo Reseda Laur do d