Its Name, the Huntington Library, Art Collections

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

National Endowment for the Arts Annual Report 1990

National Endowment For The Arts Annual Report National Endowment For The Arts 1990 Annual Report National Endowment for the Arts Washington, D.C. Dear Mr. President: I have the honor to submit to you the Annual Report of the National Endowment for the Arts for the Fiscal Year ended September 30, 1990. Respectfully, Jc Frohnmayer Chairman The President The White House Washington, D.C. April 1991 CONTENTS Chairman’s Statement ............................................................5 The Agency and its Functions .............................................29 . The National Council on the Arts ........................................30 Programs Dance ........................................................................................ 32 Design Arts .............................................................................. 53 Expansion Arts .....................................................................66 ... Folk Arts .................................................................................. 92 Inter-Arts ..................................................................................103. Literature ..............................................................................121 .... Media Arts: Film/Radio/Television ..................................137 .. Museum ................................................................................155 .... Music ....................................................................................186 .... 236 ~O~eera-Musicalater ................................................................................ -

Movers & Shakers in American Ceramics

A Ceramics Monthly Handbook Movers & Shakers in American Ceramics: Defining Twentieth Century Ceramics A Collection of Articles from Ceramics Monthly Edited by Elaine M. Levin Movers & Shakers in American Ceramics: Defining Twentieth Century Ceramics Movers & Shakers in American Ceramics: Defining Twentieth Century Ceramics A Collection of Articles from Ceramics Monthly Edited by Elaine M. Levin Published by The American Ceramic Society 600 N. Cleveland Ave., Suite 210 Westerville, Ohio 43082 USA The American Ceramic Society 600 N. Cleveland Ave., Suite 210 Westerville, OH 43082 © 2003, 2011 by The American Ceramic Society, All rights reserved. ISBN: 1-57498-165-X (Paperback) ISBN: 978-1-57498-560-3 (PDF) No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, microfilming, recording or otherwise, without written permission from the publisher, except by a reviewer, who may quote brief passages in review. Authorization to photocopy for internal or personal use beyond the limits of Sections 107 and 108 of the U.S. Copyright Law is granted by The American Ceramic Society, provided that the appropriate fee is paid directly to the Copyright Clearance Center, Inc., 222 Rosewood Drive, Danvers, MA 01923 U.S.A., www.copyright.com. Prior to photocopying items for educational classroom use, please contact Copyright Clearance Center, Inc. This consent does not extend to copyright items for general distribution or for advertising or promotional purposes or to republishing items in whole or in part in any work in any format. Requests for special photocopying permission and reprint requests should be directed to Director, Publications, The American Ceramic Society, 600 N. -

Create a High Desert Cactus Garden

Care and Maintenance Located at The cactus garden will need very little maintenance TexasA&M AgriLife Research Center once established and little or no watering will be 1380 A&M Circle needed. Cacti will be able to survive on rainfall un- El Paso, TX 79927 less the area is experiencing an extended period of drought. A little supplemental water, however, will increase the rate of growth and can result in more attractive looking plants. Just be sure not to over GARDENING IN THE DESERT SOUTHWEST PUBLICATION SERIES water. Do not water cacti during the winter months. Cacti may be fertilized sparingly in the spring with a half-strength solution. A liquid bloom-boosting fertilizer is preferred. Create a High Desert Directions: From the West, Airport/Downtown El Paso on I-10: Take exit 34, Loop 375 / Americas Avenue, 8 miles Cactus Garden from Airway Blvd. This is the first exit after Zaragosa Road. Stay on Gateway East and go under Americas. Just past where traffic is merging onto Gateway East from Americas Avenue, turn right on A&M Circle at the green sign that says “Texas A&M Research Center”. From the East on I-10: Take exit 34, Loop 375 / Americas Avenue. This is the first exit after Eastlake Dr. Stay on Gateway West (the access road paralleling the freeway) and go under Americas Avenue. Immediately after that, bear right on the cloverleaf that takes you to Americas Ave- nue south. Cross the bridge and immediately take the exit for I- 10 east / Van Horn. You will be on Gateway East. -

Volunteers in Horticulture Annual Accomplishment Report of the University of Wisconsin Extension Master Gardener Program

2011 Volunteers in Horticulture Annual Accomplishment Report of the University of Wisconsin Extension Master Gardener Program 1 The Wisconsin Master Gardener Program is administered from: The Master Gardener Program Offi ce Department of Horticulture, Room 481 University of Wisconsin Madison, WI 53706 Program Coordinator — Susan Mahr (608) 265-4504, [email protected] Interim Program Assistant — Mike Maddox (608) 265-4536, [email protected] A full copy of this report is available on the WIMGA website at wimastergardener.org 2 Table of Contents Program Highlights for 2011 . .5 Executive Summary . .6 Community Impacts in 2011 . .8 Special Report: Educating the Next Generation of Gardeners . 11 Statistical Report . .15 Local Association Narrative Reports . .17 Adams County Master Gardeners . 18 Ashland-Bayfi eld County Master Gardeners . 19 Barron County Master Gardeners . 20 Bluff Country Master Gardeners (La Crosse Co.) . 21 Calumet County Master Gardeners . 22 Chippewa Valley Master Gardeners . 23 Clark County Master Gardeners . 24 Columbia County Master Gardeners . 25 Crawford Co. Master Gardeners . 26 Dodge County Master Gardeners . 27 Door County Master Gardeners . 28 Dunn County Master Gardeners . 29 Eau Claire Area Master Gardeners (Eau Claire Co.) . 30 Fond du Lac County Master Gardeners . 31 Glacial Gardeners (Florence Co.) . 32 Grant County Master Gardeners . 33 Iowa County Master Gardeners . 34 Jackson County Master Gardeners . 35 Jefferson County Master Gardeners . 36 Juneau County Master Gardeners . 37 Lafayette County Master Gardeners . 38 Lake Superior Master Gardeners . 39 Madison Area Master Gardeners (Dane Co.) . 40 Manitowoc County Master Gardeners . 41 Master Gardeners of the North (Oneida Co.) . 42 North Central Wisconsin Master Gardeners (Marathon & Lincoln Cos.) . -

Annual Report 2013-2014

The Museum of Fine Arts, Houston Arts, Fine of Museum The μ˙ μ˙ μ˙ The Museum of Fine Arts, Houston annual report 2013–2014 THE MUSEUM OF FINE ARTS, HOUSTON, WARMLY THANKS THE 1,183 DOCENTS, VOLUNTEERS, AND MEMBERS OF THE MUSEUM’S GUILD FOR THEIR EXTRAORDINARY DEDICATION AND COMMITMENT. ANNUAL REPORT ANNUAL 2013–2014 Cover: GIUSEPPE PENONE Italian, born 1947 Albero folgorato (Thunderstuck Tree), 2012 Bronze with gold leaf 433 1/16 x 96 3/4 x 79 in. (1100 x 245.7 x 200.7 cm) Museum purchase funded by the Caroline Wiess Law Accessions Endowment Fund 2014.728 While arboreal imagery has dominated Giuseppe Penone’s sculptures across his career, monumental bronzes of storm- blasted trees have only recently appeared as major themes in his work. Albero folgorato (Thunderstuck Tree), 2012, is the culmination of this series. Cast in bronze from a willow that had been struck by lightning, it both captures a moment in time and stands fixed as a profoundly evocative and timeless monument. ALG Opposite: LYONEL FEININGER American, 1871–1956 Self-Portrait, 1915 Oil on canvas 39 1/2 x 31 1/2 in. (100.3 x 80 cm) Museum purchase funded by the Caroline Wiess Law Accessions Endowment Fund 2014.756 Lyonel Feininger’s 1915 self-portrait unites the psychological urgency of German Expressionism with the formal structures of Cubism to reveal the artist’s profound isolation as a man in self-imposed exile, an American of German descent, who found himself an alien enemy living in Germany at the outbreak of World War I. -

Garden Views

GARDEN VIEWS UCCE Riverside County Master Gardener Program Newsletter October 2017 University of California Cooperative Extension - Riverside County 21150 Box Springs Road, #202 Moreno Valley, CA 92557-8781 (951) 683-6491 x231 81077 Indio Blvd., Suite H Indio, CA 92201 (760) 342-6437 Website www.ucanr.edu/sites/RiversideMG Email [email protected] [email protected] In This Issue Queen of the Grow Lab, Linda Zummo ........................................... 1 Low-Cost, Desert Day-Trips for Garden Lovers: Trip Number One .. 2 UCR’S 35th Fall Plant Sale .............. 4 La Gran Fiesta ................................. 4 2017-2018 Gold Miners ................. 5 WMWD Garden Committee ........... 6 Fall Kick-Off Social .......................... 7 University of California Riverside Botanic Gardens ........................... 10 Queen of the Grow Lab, Linda Zummo Janet’s Jottings ............................. 10 Linda Zummo has done an excellent job as the Coordinator. Her Editor’s Remarks .......................... 11 personal efforts make Grow Lab an important learning environment. Preparation for the plant sales can be an overwhelming task, but Linda has a great team to share the load. The income from Grow Lab sales contributes much of our annual budget. We all owe a great round of applause and a sincere Thank You to Linda and her team of Master Gardener Volunteers. 1 of 11 GARDEN VIEWS October 2017 The Teddy bear cactus garden in Joshua Tree National Park along Low-Cost, Desert Day-Trips the route to Cottonwood. for Garden Lovers: Trip Number One by Ron Jemmerson, DAB Chair Have you ever entertained an out-of-town guest and Cacti, in particular barrel cacti, become more run out of low-cost things to do? Consider a day trip in pronounced on the low mountains as you wind your the Southern California deserts. -

At Long Last Love Press Release

At Long Last Love: Fiber Sculpture Gets Its Due October 2014 It looks as if 2014 will be the year that contemporary fiber art finally gets the recognition and respect it deserves. For us, it kicked off at the Whitney Biennial in May which gave pride of place to Sheila Hicks’ massive cascade, Pillar of Inquiry/Supple Column. Last month saw the opening of the influential Thread Lines, at The Drawing Center in New York featuring work by 16 artists who sew, stitch and weave. Now at the Institute of Contemporary Art in Boston, the development of ab- straction and dimensionality in fiber art from the mid-twentieth centu- ry through to the present is examined in Fiber: Sculpture 1960–present from October 1st through January 4, 2015. The exhibition features 50 works by 34 artists, who crisscross generations, nationalities, processes and aesthetics. It is accompanied by an attractive companion volume, Fiber: Sculpture 1960-present available at browngrotta.com. There are some standout works in the exhibition — we were thrilled Fiber: Sculpture 1960 — present opening photo by Tom Grotta to see Naomi Kobayashi’s Ito wa Ito (1980) and Elsi Giauque’s Spatial Element (1989), on loan from European museums, in person after ad- miring them in photographs. Anne Wilson’s Blonde is exceptional and Ritzi Jacobi and Françoise Grossen are represented by strong works, too, White Exotica (1978, created with Peter Jacobi) and Inchworm, respectively. Fiber: Sculpture 1960–present aims to create a sculp- tural dialogue, an art dialogue — not one about craft, ICA Mannion Family Senior Curator Jenelle Porter explained in an opening-night conversation with Glenn Adamson, Director, Museum of Arts and Design. -

CACTUS CHRONICLE Party

Volume 81 Issue 6 Holiday CACTUS CHRONICLE Party Mission Statement: CSSA Affiliate The Los Angeles Cactus and Succulent Society (LACSS) cultivates the study and enjoy- ment of cacti and succulent plants through educational programs and activities that promote Next Meeting the hobby within a community of fellow enthusiasts and among the greater public. Thursday June 4th, 2015 Program: Madagascar: The Island of the Big Trees 16633 Magnolia Blvd. Presented by Guillermo Rivera Encino, CA 91356 Doors Open at 6:15 pm This presentation will cover a recent jour- Meeting begins at ney to the western and southern part of 7:00pm the Island of Madagascar. The island is not only rich in endemism (plants that are only found in this place), but also with ani- Refreshments mals that are unique to this environment. Lemurs and Chameleons are almost ex- clusively found in Madagascar. Among the plants, the genus Adansonia is perhaps N-R the most common, but plenty of Aloes, Eu- phorbias, Didiereas, Alluaudias, and Pachypodiums can be found as well. Born in Argentina, he is owner of South Editor America Nature Tours (formerly Cactus Phyllis Frieze Expeditions). For the past 12 years his frieze.phyllis@ company has been dedicated to the or- yahoo.com ganization of tours to such locations as- South America (Chile, Argentina, Brazil, Peru, Colombia, Bolivia, Ecuador), Mexico and South Africa, with emphasis on plant habitats (bromeliads, cacti, and orchids), and birding. Guillermo is a former re- searcher at the University of Cordoba, Ar- gentina. He has a BS degree in Biology Visit Us on the web from the University in Cordoba and an MS www.LAcactus.com. -

Ontario Crafts Council Periodical Listing Compiled By: Caoimhe Morgan-Feir and Amy C

OCC Periodical Listing Compiled by: Caoimhe Morgan-Feir Amy C. Wallace Ontario Crafts Council Periodical Listing Compiled by: Caoimhe Morgan-Feir and Amy C. Wallace Compiled in: June to August 2010 Last Updated: 17-Aug-10 Periodical Year Season Vo. No. Article Title Author Last Author First Pages Keywords Abstract Craftsman 1976 April 1 1 In Celebration of pp. 1-10 Official opening, OCC headquarters, This article is a series of photographs and the Ontario Crafts Crossroads, Joan Chalmers, Thoma Ewen, blurbs detailing the official opening of the Council Tamara Jaworska, Dora de Pedery, Judith OCC, the Crossroads exhibition, and some Almond-Best, Stan Wellington, David behind the scenes with the Council. Reid, Karl Schantz, Sandra Dunn. Craftsman 1976 April 1 1 Hi Fibres '76 p. 12 Exhibition, sculptural works, textile forms, This article details Hi Fibres '76, an OCC Gallery, Deirdre Spencer, Handcraft exhibition of sculptural works and textile House, Lynda Gammon, Madeleine forms in the gallery of the Ontario Crafts Chisholm, Charlotte Trende, Setsuko Council throughout February. Piroche, Bob Polinsky, Evelyn Roth, Charlotte Schneider, Phyllis gerhardt, Dianne Jillings, Joyce Cosgrove, Sue Proom, Margery Powel, Miriam McCarrell, Robert Held. Craftsman 1976 April 1 2 Communications pp. 1-6 First conference, structures and This article discusses the initial Weekend programs, Alan Gregson, delegates. conference of the OCC, in which the structure of the organization, the programs, and the affiliates benefits were discussed. Page 1 of 153 OCC Periodical Listing Compiled by: Caoimhe Morgan-Feir Amy C. Wallace Periodical Year Season Vo. No. Article Title Author Last Author First Pages Keywords Abstract Craftsman 1976 April 1 2 The Affiliates of pp. -

Charles Glass…In His Own Words INTRODUCTION by VIRGINIA HAYES

LOTUSLAND NEWSLETTER FOR MEMBERS ◆ VOLUME 18 NO. 2 ◆ SPRING 2009 Charles Glass…In His Own Words INTRODUCTION BY VIRGINIA HAYES HARLES GLASS came to work at Lotusland with his business partner C Robert Foster in 1973. Foster soon decided to go back to his other work as a cactus and succulent specialist, and Glass continued on as the director of the garden until 1983. During his tenure, the original succulent garden was renovated and many new specimens added, the cacti and euphorbias were reorganized and replanted along the main driveway, and the aloe garden was totally revamped with impressive boulders and many more species of aloes. His largest project was the design and installation of the cycad garden, but he was also instrumental in adding azaleas to the Japanese garden, renovating the upper bromeliad garden and creating the lower bromeliad garden as well as all of the myriad tasks necessary to maintain the property. Glass was dedicated to Madame SYLVESTER Walska and her vision for Lotusland. Ten years before his death in 1998, he wrote ARTHUR ARTHUR of his experiences with her and in the Glass (FAR RIGHT) and Madame Walska (CENTER) escort visitors through the garden on this rare public tour garden. With this issue of the Newsletter in 1978. for Members, we begin a series of excerpts from his unpublished memoir with the IN THIS ISSUE working title of Experiences of 12 Years as Director of Lotusland: The Fabulous Estate Charles Glass…In His Own Words 1 Summer Solstice Twilight Tour 10 of Mme. Ganna Walska. Director’s Letter 3 Volunteer Profile: Alan Johnston 11 LotusFest! 4 Captivated by Nature’s Wonders HAD MANY TIMES thought of Mother’s Day Tea and Tour 11 writing of my experiences with New to the Collections 5 IMme. -

Textile Society of America Newsletter 27:2 — Fall 2015 Textile Society of America

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Textile Society of America Newsletters Textile Society of America Fall 2015 Textile Society of America Newsletter 27:2 — Fall 2015 Textile Society of America Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/tsanews Part of the Art and Design Commons Textile Society of America, "Textile Society of America Newsletter 27:2 — Fall 2015" (2015). Textile Society of America Newsletters. 71. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/tsanews/71 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Textile Society of America at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Textile Society of America Newsletters by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. VOLUME 27. NUMBER 2. FALL, 2015 Cover Image: Collaborative work by Pat Hickman and David Bacharach, Luminaria, 2015, steel, animal membrane, 17” x 23” x 21”, photo by George Potanovic, Jr. page 27 Fall 2015 1 Newsletter Team BOARD OF DIRECTORS Roxane Shaughnessy Editor-in-Chief: Wendy Weiss (TSA Board Member/Director of External Relations) President Designer and Editor: Tali Weinberg (Executive Director) [email protected] Member News Editor: Ellyane Hutchinson (Website Coordinator) International Report: Dominique Cardon (International Advisor to the Board) Vita Plume Vice President/President Elect Editorial Assistance: Roxane Shaughnessy (TSA President) and Vita Plume (Vice President) [email protected] Elena Phipps Our Mission Past President [email protected] The Textile Society of America is a 501(c)3 nonprofit that provides an international forum for the exchange and dissemination of textile knowledge from artistic, cultural, economic, historic, Maleyne Syracuse political, social, and technical perspectives. -

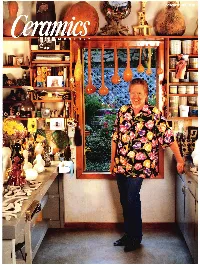

Adrian Saxe by Elaine Levin

October 1993 1 William Hunt.................................... Editor Ruth C. Butler ................Associate Editor Robert L. Creager..................... Art Director Kim Nagorski..... .............Assistant Editor Mary Rushley ............... Circulation Manager Mary E. Beaver ....Assistant Circulation Manager Connie Belcher .......Advertising Manager Spencer L. Davis .......................... Publisher Editorial, Advertising and Circulation Offices 1609 Northwest Boulevard Post Office Box 12448 Columbus, Ohio 43212 (614) 488-8236 FAX (614) 488-4561 Ceramics Monthly (ISSN 0009-0328) is pub lished monthly except July and August by Profes sional Publications, Inc., 1609 Northwest Bou levard, Columbus, Ohio 43212. Second Class postage paid at Columbus, Ohio. Subscription Rates: One year $22, two years $40, three years $55. Add $10 per year for subscriptions outside the U.S.A. In Canada, also add GST (registration number R123994618). Change of Address:Please give us four weeks advance notice. Send the magazine address label as well as your new address to: Ceramics Monthly, Circulation Offices, Post Office Box 12448, Columbus, Ohio 43212. Contributors: Manuscripts, announcements, news releases, photographs, color separations, color transparencies (including 35mm slides), graphic illustrations and digital TIFF or EPS im ages are welcome and will be considered for publication. Mail submissions to Ceramics Monthly, Post Office Box 12448, Columbus, Ohio 43212. We also accept unillustrated mate rials faxed to (614) 488-4561. Writing and Photographic Guidelines:A book let describing standards and procedures for sub mitting materials is available upon request. Indexing:An index of each year’s articles appears in the December issue. Additionally, Ceramics Monthly articles are indexed in the Art Index. Printed, on-line and CD-ROM (computer) index ing is available through Wilsonline, 950 Univer sity Avenue, Bronx, New York 10452; and from Information Access Company, 362 Lakeside Drive, Forest City, California 94404.