Pacific People in Cannons Creek/Waitangirua: Movement and Attachment

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

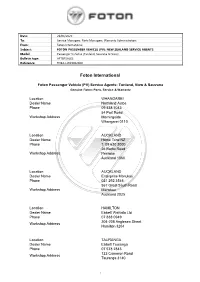

Foton International

Date: 23/06/2020 To: Service Managers, Parts Managers, Warranty Administrators From: Foton International Subject: FOTON PASSENGER VEHICLE (PV): NEW ZEALAND SERVICE AGENTS Model: Passenger Vehicles (Tunland, Sauvana & View) Bulletin type: AFTERSALES Reference: FDBA-LW23062020 Foton International Foton Passenger Vehicle (PV) Service Agents: Tunland, View & Sauvana Genuine Foton: Parts, Service & Warranty Location WHANGAREI Dealer Name Northland Autos Phone 09 438 7043 54 Port Road Workshop Address Morningside Whangarei 0110 Location AUCKLAND Dealer Name Home Tune NZ Phone T: 09 630 3000 26 Botha Road Workshop Address Penrose Auckland 1060 Location AUCKLAND Dealer Name Enterprise Manukau Phone 021 292 3546 567 Great South Road Workshop Address Manukau Auckland 2025 Location HAMILTON Dealer Name Ebbett Waikato Ltd Phone 07 838 0949 204-208 Anglesea Street Workshop Address Hamilton 3204 Location TAURANGA Dealer Name Ebbett Tauranga Phone 07 578 2843 123 Cameron Road Workshop Address Tauranga 3140 1 Location ROTORUA Dealer Name Grant Johnstone Motors Phone 07 349 2221 24-26 Fairy Springs Road Workshop Address Fairy Springs Rotorua 2104 Location TAUPO Dealer Name Central Motor Hub Phone 022 046 5269 79 Miro Street Workshop Address Tauhara Taupo 3330 Location GISBORNE Dealer Name Enterprise Motors Phone 06 867 8368 323 Gladstone Rd Workshop Address Gisborne 4010 Location HASTINGS Dealer Name The Car Company Phone 06 870 9951 909 Karamu Road North Workshop Address Hastings 4122 Location NEW PLYMOUTH Dealer Name Ross Graham Motors Ltd Phone 06 -

Porirua Harbour Intertidal Fine Scale Monitoring 2008/9

Wriggle coastalmanagement Porirua Harbour Intertidal Fine Scale Monitoring 2008/09 Prepared for Greater Wellington Regional Council June 2009 Porirua Harbour Intertidal Fine Scale Monitoring 2008/09 Prepared for Greater Wellington Regional Council By Barry Robertson and Leigh Stevens Cover Photo: Upper Pauatahanui Arm of Porirua Harbour from mouth of Pautahanui Stream. Wriggle Limited, PO Box 1622, Nelson 7040, Ph 0275 417 935, 021 417 936, www.wriggle.co.nz Wriggle coastalmanagement iii Contents Porirua Harbour 2009 - Executive Summary . vii 1. Introduction . 1 2. Methods . 4 3. Results and Discussion . 8 4. Conclusions . 15 5. Monitoring ���������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������� 15 6. Management ������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������ 15 8. References ���������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������� 16 Appendix 1. Details on Analytical Methods �������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������� 17 Appendix 2. 2009 Detailed Results . 17 Appendix 3. Infauna Characteristics . 23 List of Figures Figure 1. Location of sedimentation and fine scale monitoring -

The Native Land Court, Land Titles and Crown Land Purchasing in the Rohe Potae District, 1866 ‐ 1907

Wai 898 #A79 The Native Land Court, land titles and Crown land purchasing in the Rohe Potae district, 1866 ‐ 1907 A report for the Te Rohe Potae district inquiry (Wai 898) Paul Husbands James Stuart Mitchell November 2011 ii Contents Introduction ........................................................................................................................................... 1 Report summary .................................................................................................................................. 1 The Statements of Claim ..................................................................................................................... 3 The report and the Te Rohe Potae district inquiry .............................................................................. 5 The research questions ........................................................................................................................ 6 Relationship to other reports in the casebook ..................................................................................... 8 The Native Land Court and previous Tribunal inquiries .................................................................. 10 Sources .............................................................................................................................................. 10 The report’s chapters ......................................................................................................................... 20 Terminology ..................................................................................................................................... -

REFEREES the Following Are Amongst Those Who Have Acted As Referees During the Production of Volumes 1 to 25 of the New Zealand Journal of Forestry Science

105 REFEREES The following are amongst those who have acted as referees during the production of Volumes 1 to 25 of the New Zealand Journal of Forestry Science. Unfortunately, there are no records listing those who assisted with the first few volumes. Aber, J. (University of Wisconsin, Madison) AboEl-Nil, M. (King Feisal University, Saudi Arabia) Adams, J.A. (Lincoln University, Canterbury) Adams, M. (University of Melbourne, Victoria) Agren, G. (Swedish University of Agricultural Science, Uppsala) Aitken-Christie, J. (NZ FRI, Rotorua) Allbrook, R. (University of Waikato, Hamilton) Allen, J.D. (University of Canterbury, Christchurch) Allen, R. (NZ FRI, Christchurch) Allison, B.J. (Tokoroa) Allison, R.W. (NZ FRI, Rotorua) Alma, P.J. (NZ FRI, Rotorua) Amerson, H.V. (North Carolina State University, Raleigh) Anderson, J.A. (NZ FRI, Rotorua) Andrew, LA. (NZ FRI, Rotorua) Andrew, LA. (Telstra, Brisbane) Armitage, I. (NZ Forest Service) Attiwill, P.M. (University of Melbourne, Victoria) Bachelor, C.L. (NZ FRI, Christchurch) Bacon, G. (Queensland Dept of Forestry, Brisbane) Bagnall, R. (NZ Forest Service, Nelson) Bain, J. (NZ FRI, Rotorua) Baker, T.G. (University of Melbourne, Victoria) Ball, P.R. (Palmerston North) Ballard, R. (NZ FRI, Rotorua) Bannister, M.H. (NZ FRI, Rotorua) Baradat, Ph. (Bordeaux) Barr, C. (Ministry of Forestry, Rotorua) Bartram, D, (Ministry of Forestry, Kaikohe) Bassett, C. (Ngaio, Wellington) Bassett, C. (NZ FRI, Rotorua) Bathgate, J.L. (Ministry of Forestry, Rotorua) Bathgate, J.L. (NZ Forest Service, Wellington) Baxter, R. (Sittingbourne Research Centre, Kent) Beath, T. (ANM Ltd, Tumut) Beauregard, R. (NZ FRI, Rotorua) New Zealand Journal of Forestry Science 28(1): 105-119 (1998) 106 New Zealand Journal of Forestry Science 28(1) Beekhuis, J. -

Prospectus.2021

2021 PROSPECTUS Contents Explanation 1 Tuia Overview 2 Rangatahi Selection 3 Selection Process 4 Mayoral/Mentor and Rangatahi Expectations 6 Community Contribution 7 Examples 8 Rangatahi Stories 9 Bronson’s story 9 Maui’s story 11 Puawai’s story 12 Tuia Timeframes 14 Key Contacts 15 Participating Mayors 2011-2020 16 Explanation Tōia mai ngā tāonga a ngā mātua tīpuna. Tuia i runga, tuia i raro, tuia i roto, tuia i waho, tuia te here tāngata. Ka rongo te pō, ka rongo te ao. Tuia ngā rangatahi puta noa i te motu kia pupū ake te mana Māori. Ko te kotahitanga te waka e kawe nei te oranga mō ngā whānau, mō ngā hapū, mō ngā iwi. Poipoia te rangatahi, ka puta, ka ora. The name ‘Tuia’ is derived from a tauparapara (Māori proverbial saying) that is hundreds of years old. This saying recognises and explains the potential that lies within meaningful connections to: the past, present and future; to self; and to people, place and environment. The word ‘Tuia’ means to weave and when people are woven together well, their collective contribution has a greater positive impact on community. We as a rangatahi (youth) leadership programme look to embody this by connecting young Māori from across Aotearoa/New Zealand - connecting passions, aspirations and dreams of rangatahi to serve our communities well. 1 Tuia Overview Tuia is an intentional, long-term, intergenerational approach to develop and enhance the way in which rangatahi Māori contribute to communities throughout New Zealand. We look to build a network for rangatahi to help support them in their contribution to their communities. -

PLIMMERTON FARM SUBMISSION | K BEAMSLEY Page 1

PLIMMERTON FARM – PLAN CHANGE PROPOSAL Supporting Documentation View from Submitters Property Karla and Trevor Beamsley 24 Motuhara Road Plimmerton PLIMMERTON FARM SUBMISSION | K BEAMSLEY Page 1 1. INTRODUCTION The village of Plimmerton is a northern suburb of Porirua, and is surrounded to the North and East by farmland. It represents the edge of existing residential dwellings. Generally existing homes are stand-alone dwellings on lots greater than 500m² in size. Most residents within Plimmerton and Camborne either commute into Wellington city or work from home. The demand for housing in this area is from professional couples or families looking for 3 – 4 bedroom family homes on a section with space for kids to run around in, not medium or high density three-storey buildings and apartments, this is reflected in the TPG report to PCC (Dec 2019). Medium density style townhouses, or apartments would be totally out of character of the surrounding residential areas, and would present a stark contrast to the remaining rural areas which bound the site. The Plimmerton Farm site is not located close to areas of high employment, nor is it close to local amenities like the main shopping areas of Porirua. The site is also not located within an area currently supported by existing infrastructure. Much of the infrastructure in the area is aging, and requires repair or upgrade to support existing demands. Therefore, the idea that Plimmerton Farm would provide homes in a location close to employment, amenities and infrastructure1 is simply incorrect in terms of a 10-year time frame. Areas where this would be true include the currently developing areas of Aotea, Whitby, Kenepuru, and Porirua East. -

Porirua Stream Walkway

Porirua Stream Walkway Route Analysis & Definition Study Cover Image: The valley floor of Tawa, with the bridge at McLellan Street in the foreground, 1906 Tawa - Enterprise and Endeavour by Ken Cassells, 1988 Porirua Stream Walkway – Route Analysis & Definition Study Porirua Stream Walkway Scoping Report & Implementation Strategy Prepared By Opus International Consultants Limited Noelia Martinez Wellington Office Graduate Civil Engineer Level 9, Majestic Centre, 100 Willis Street PO Box 12 003, Wellington 6144, Reviewed By New Zealand Roger Burra Senior Transport Planner Telephone: +64 4 471 7000 Facsimile: +64 4 471 7770 Released By Bruce Curtain Date: 24 March 2009 Principal Urban Designer Reference: 460535.00 Status: FINAL Rev 02 © Opus International Consultants Limited 2008 March 2008 3 Wellington City Council Reference: 460535.00 Status: FINAL Rev 02 Parks & Gardens Porirua Stream Walkway – Route Analysis & Definition Study March 2008 i Wellington City Council Reference: 460535.00 Status: FINAL Rev 02 Parks & Gardens Porirua Stream Walkway – Route Analysis & Definition Study Contents 1 Introduction APPENDIX A – Option Details ..........................................................................................35 1.1 Project Objectives.........................................................................................................3 1.2 Policy Context ...............................................................................................................4 APPENDIX B – Earthworks Comments ...........................................................................43 -

Porirua City / [email protected] / P

SEPTEMBER 2018 PORIRUA CITY WWW.INTEREST.CO.NZ / [email protected] / P. 09 3609670 PORIRUA CITY HOME LOAN AFFORDABILITY REPORT September 2018 Home loan affordability is a measure of the proportion of take-home pay that is needed to make the mortgage payment for a typical household. If that is less than 40%, then a mortgage is considered ‘affordable’. The following are typical assessments for households at three stages of home ownership. FIRST HOME BUYERS 25-29 YOUNG FAMILY 30-34 OLDER FAMILY 35-39 First home buyers earn a medi- Young family buyers earn medi- Older family buyers earn medi- an income for their age group, an incomes in their age bracket, an incomes in their age brack- and buy a first quartile house and buy a median house in et, and buy a median house in in their area. Both parties work their area. One partner works their area. Both partners work full-time. half-time. full-time. Mortgage payment as a Mortgage payment as a Mortgage payment as a percentage of the take home pay percentage of the take home pay percentage of the take home pay Take Home Septem- 33.1% Take Home Septem- 30.9% Take Home Septem- 21.0% Pay ber 18 Pay ber 18 Pay $1,588.95 ber 18 Septem- 28.5% $1,398.29 Septem- 33.5% $1,943.93 per Week per Week per Week Septem- 20.1% ber 17 ber 17 ber 17 Septem- 24.0% Septem- 28.5% Septem- 17.1% ber 16 ber 16 ber 16 This report estimates how affordable it would be for a couple This report estimates how affordable it would be for a couple This report estimates how affordable it would be for a couple where both are aged 25–29 and are working full time, to buy a with a young family to move up the property ladder and buy their who are both aged 35-39 and working full time, to move up the home at the lower quartile price in Porirua City. -

1 Decision of the Otorohanga District Licensing Committee

OTOROHANGA DISTRICT LICENSING COMMITTEE Application 018-0013 IN THE MATTER of the Sale and Supply of Alcohol Act 2012 AND of an application by IN THE MATTER J & J Clark Limited trading as Kawhia General Store for the renewal of an off-licence pursuant to section 127 of the Act OTOROHANGA DISTRICT LICENSING COMMITTEE Chairperson: Mrs S Grayson Members: Cr R Johnson, Mr R Murphy HEARING at the Te Awamutu Fire Station Hall on 7 July 2017 APPEARANCES Mrs J Clark, director of J & J Clark Limited - Applicant Mr R Davies, counsel for J & J Clark Limited Miss N Petersen, Medical Officer of Health Mr K Tutty, Licensing Inspector Sergeant J Kernohan, Police HEARING at the Waipa District Council Chambers on 6 April 2018 APPEARANCES Mrs J Clark, director of J & J Clark Limited – Applicant Mr J Clark, director of J & J Clark Limited - Applicant Mr R Davies, counsel for J & J Clark Limited Mrs N Zeier, Medical Officer of Health Mrs M Fernandez, Licensing Inspector DECISION OF THE OTOROHANGA DISTRICT LICENSING COMMITTEE 1. The off-licence 018/OFF/006/15 in respect of the premises situated at 29 Jervois Street, Kawhia and known as Kawhia General Store is renewed for a further period of 3 years. The licence may issue upon payment of the annual fee. 1 2. The present conditions of the licence are replaced as follows (a) Alcohol may be sold or delivered on Monday to Sunday, from 8.00am to 8.00pm. (b) No alcohol may be sold on the premises on Good Friday, Easter Sunday, Christmas Day, or before 1.00pm on Anzac Day. -

Historical Snapshot of Porirua

HISTORICAL SNAPSHOT OF PORIRUA This report details the history of Porirua in order to inform the development of a ‘decolonised city’. It explains the processes which have led to present day Porirua City being as it is today. It begins by explaining the city’s origins and its first settlers, describing not only the first people to discover and settle in Porirua, but also the migration of Ngāti Toa and how they became mana whenua of the area. This report discusses the many theories on the origin and meaning behind the name Porirua, before moving on to discuss the marae establishments of the past and present. A large section of this report concerns itself with the impact that colonisation had on Porirua and its people. These impacts are physically repre- sented in the city’s current urban form and the fifth section of this report looks at how this development took place. The report then looks at how legislation has impacted on Ngāti Toa’s ability to retain their land and their recent response to this legislation. The final section of this report looks at the historical impact of religion, particularly the impact of Mormonism on Māori communities. Please note that this document was prepared using a number of sources and may differ from Ngati Toa Rangatira accounts. MĀORI SETTLEMENT The site where both the Porirua and Pauatahanui inlets meet is called Paremata Point and this area has been occupied by a range of iwi and hapū since at least 1450AD (Stodart, 1993). Paremata Point was known for its abundant natural resources (Stodart, 1993). -

Porirua City / [email protected] / P

APRIL 2020 PORIRUA CITY WWW.INTEREST.CO.NZ / [email protected] / P. 09 3609670 PORIRUA CITY HOME LOAN AFFORDABILITY REPORT April 2020 Home loan affordability is a measure of the proportion of take-home pay that is needed to make the mortgage payment for a typical household. If that is less than 40%, then a mortgage is considered ‘affordable’. The following are typical assessments for households at three stages of home ownership. FIRST HOME BUYERS 25-29 YOUNG FAMILY 30-34 OLDER FAMILY 35-39 First home buyers earn a medi- Young family buyers earn medi- Older family buyers earn medi- an income for their age group, an incomes in their age bracket, an incomes in their age brack- and buy a first quartile house and buy a median house in et, and buy a median house in in their area. Both parties work their area. One partner works their area. Both partners work full-time. half-time. full-time. Mortgage payment as a Mortgage payment as a Mortgage payment as a percentage of the take home pay percentage of the take home pay percentage of the take home pay Take Home Take Home Take Home April 20 36.1% April 20 21.8% April 20 13.7% Pay Pay Pay $1,648.44 April 19 27.9% $1,446.82 April 19 28.2% $2,013.47 April 19 17.8% per Week per Week per Week April 18 27.6% April 18 24.6% April 18 18.0% This report estimates how affordable it would be for a couple This report estimates how affordable it would be for a couple This report estimates how affordable it would be for a couple where both are aged 25–29 and are working full time, to buy a with a young family to move up the property ladder and buy their who are both aged 35-39 and working full time, to move up the home at the lower quartile price in Porirua City. -

Porirua – Our Place, Our Future, Our Challenge Let's Kōrero

COPYRIGHT © You are free to copy, distribute and adapt the work, as long as you attribute the work to Porirua City Council. Published March 2021. Porirua City Council 16 Cobham Court PO Box 50218 Porirua 5240 This document is available on our website poriruacity.govt.nz Porirua – our place, our future, our challenge Let’s kōrero Consultation Document for the proposed Long-term Plan 2021-51 Message from Ngāti Toa Rangatira E te iwi e noho nei i te riu o Porirua, tēnā koutou katoa The development of the city's Long-term Plan 2021-2051 will bring changes to our city that we will be proud of. Between now and 2051 we will see Porirua transform into a vibrant and exciting place to be for residents and people who choose to work here. We are blessed with hills, waterways, Te Mana o Kupe bushwalks and two magnificent harbours, Porirua and Pāuatahanui, as well as rich histories all anchored by Te Matahourua, the anchor left here by Kupe. As a challenge to all of us – we must look after our environment and look after each other, especially our tamariki and rangatahi. Nou te rourou, naku te rourou ka ora ai te Iwi With your contribution, and my contribution the people will thrive Taku Parai Chairman, Te Rūnanga o Ngāti Toa Rangatira 2 Consultation Document for the proposed LTP 2021-51 Contents Mai i tō Koutou Koromatua 4 From your Mayor Executive summary 8 Rates 10 The challenges for our city 11 Your views 16 Investment in the 3 waters – drinking water, wastewater 17 & stormwater 1.