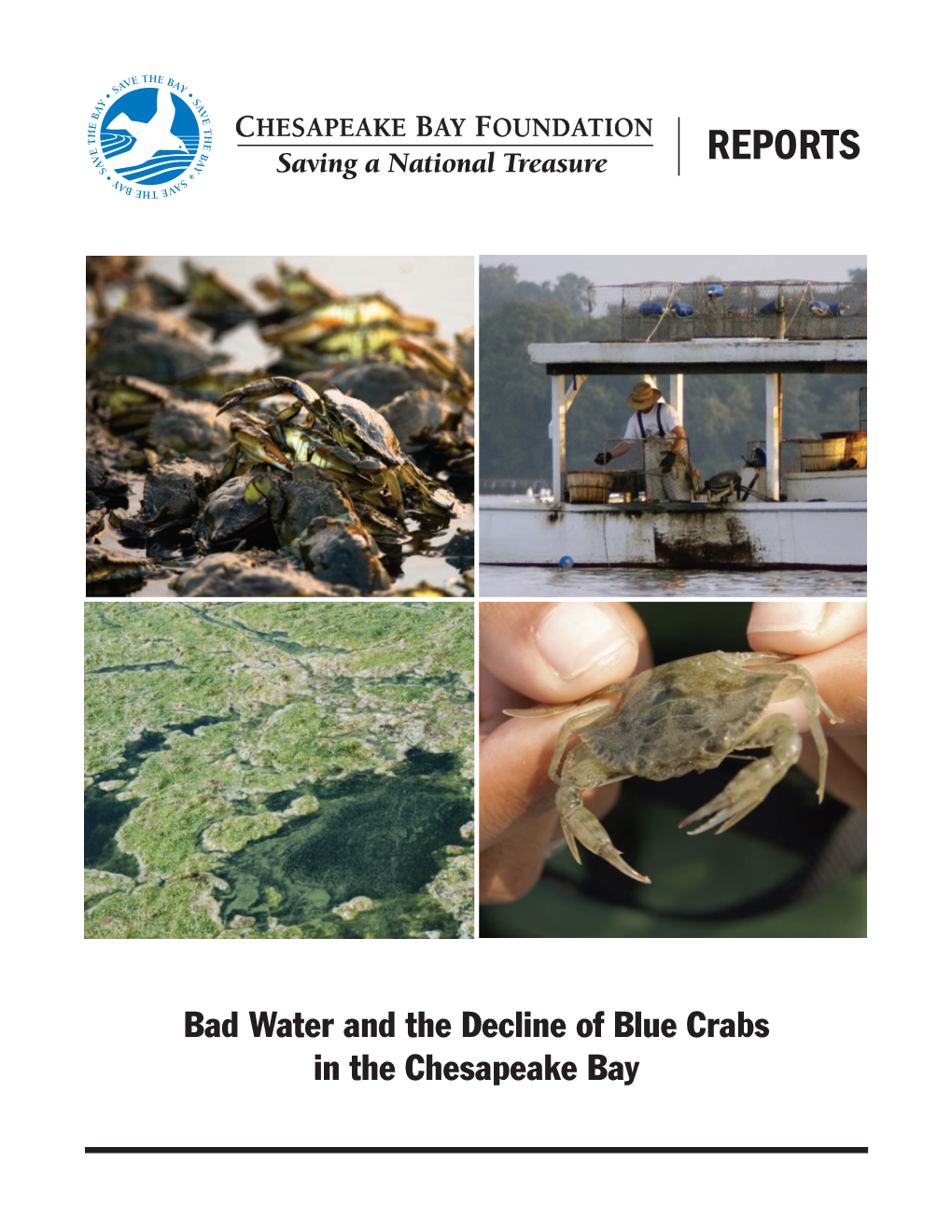

Bad Water and the Decline of Blue Crabs in the Chesapeake

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Tournament Rules Match Rules Net Run Rate

Tournament Rules - Only employees nominated by member AMCs holding valid employment card shall be allowed to participate. - Organizing committee is providing all teams with 15 color kits. No one will be allowed to wear any other kit. Extra kits (on request) would cost PKR 2,000 per kit. Teams may give names of maximum 18 players. - The tournament will consist of 12 teams in total, divided in 2 groups with each team playing 5 group matches. - At the end of the league matches, top 2 teams from each group will qualify for the semi-finals. - Points shall be awarded on the following system: win/walkover (3pts), tie/washout (1pt), lost (0pts). - In case the points are equal, the team with better net run rate (NRR) will qualify for the semi- finals (the formula is given below). - The reporting time for the morning match will be 9:00am sharp (toss at 9:15am and match would start at 9:30am) and for the afternoon match the reporting time will be 1:00pm sharp (toss at 1:15pm and match would start at 1:30pm). - Walkover will be awarded in the event if a team (minimum of 7 players) fails to appear within 30 minutes of the scheduled time of the allotted time. - In the case of a tie in a knockout match, the result will be decided by a super-over. - The team's captain will have the responsibility of maintaining discipline and healthy atmosphere during the matches, any grievances should be brought to committee's notice by the captain only. -

THE ECONOMIC EFFECTS of a DECLINING POPULATION by FRANCOIS LAFITTE Itstroduction I5-64) Will Grow Older

THE ECONOMIC EFFECTS OF A DECLINING POPULATION By FRANCOIS LAFITTE Itstroduction I5-64) will grow older. Between I89I and AWELL-CONCEIVED population I937 its average age rose by 24 years, from policy cannot be elaborated unless 34-3 to 36-9 years. In the coming forty the most careful and objective assess- years Glass's projections suggest a further ment of the consequences of present popula- ageing of between 3j and 6 years. Wil this. tion trends is first attempted. If we wish to affect the productivity of the worker ad- modify the British demographic situation versely ? We do not know, but, since the' we have to know why it needs modifying, whole trend of industrial technique is away and in what direction it should be guided. from types of work involving great physical The consequences of differential fertility strength, I doubt whether any possible and mortality are the main concern of deterioration of productivity due to ageing eugenists, and less attention has been of the working population could not be made devoted to the possible effects of changes in up for by improvements in health and work- age composition and total numbers. The ing conditions. In any case, productivity present article is limited to a discussion of per operative employed in Britain rose by the latter in relation to Britain's economic 7 per cent in I924-30 and by at least 20 per future, and is written in lieu of a review of cent in I930-35, whilst in the U.S.A. physical W. B. Reddaway's The Economics of a output per man-hour in industry rose by 27 Declining Population (I939)*, the first sys- per cent in I929-35. -

Who Fears and Who Welcomes Population Decline?

Demographic Research a free, expedited, online journal of peer-reviewed research and commentary in the population sciences published by the Max Planck Institute for Demographic Research Konrad-Zuse Str. 1, D-18057 Rostock · GERMANY www.demographic-research.org DEMOGRAPHIC RESEARCH VOLUME 25, ARTICLE 13, PAGES 437-464 PUBLISHED 12 AUGUST 2011 http://www.demographic-research.org/Volumes/Vol25/13/ DOI: 10.4054/DemRes.2011.25.13 Research Article Who fears and who welcomes population decline? Hendrik P. van Dalen Kène Henkens © 2011 Hendrik P. van Dalen & Kène Henkens. This open-access work is published under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial License 2.0 Germany, which permits use, reproduction & distribution in any medium for non-commercial purposes, provided the original author(s) and source are given credit. See http:// creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/2.0/de/ Table of Contents 1 Introduction 438 2 Population decline: Stylized facts and forecasts 440 3 Population decline and theory 444 3.1 Negative consequences of decline 444 3.2 Positive consequences of decline 447 3.3 The tension between immigration and population decline 448 4 Data and method 449 5 Explaining population size preferences 451 6 Conclusion and discussion 457 7 Acknowledgements 459 References 460 Appendix: Properties of scale variables 463 Demographic Research: Volume 25, Article 13 Research Article Who fears and who welcomes population decline? Hendrik P. van Dalen1 Kène Henkens2 Abstract European countries are experiencing population decline, and the tacit assumption in most analyses is that this decline may have detrimental effects on welfare. In this paper, we use a survey conducted in the Netherlands to find out whether population decline is always met with fear. -

New Perspectives on Tibetan Fertility and Population Decline Author(S): Melvyn C

New Perspectives on Tibetan Fertility and Population Decline Author(s): Melvyn C. Goldstein Source: American Ethnologist, Vol. 8, No. 4 (Nov., 1981), pp. 721-738 Published by: Blackwell Publishing on behalf of the American Anthropological Association Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/643961 Accessed: 11/10/2010 09:36 Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use, available at http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp. JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use provides, in part, that unless you have obtained prior permission, you may not download an entire issue of a journal or multiple copies of articles, and you may use content in the JSTOR archive only for your personal, non-commercial use. Please contact the publisher regarding any further use of this work. Publisher contact information may be obtained at http://www.jstor.org/action/showPublisher?publisherCode=black. Each copy of any part of a JSTOR transmission must contain the same copyright notice that appears on the screen or printed page of such transmission. JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. Blackwell Publishing and American Anthropological Association are collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to American Ethnologist. http://www.jstor.org new perspectives on Tibetan fertility and population decline MELVYN C. -

Causes of Urban Shrinkage: an Overview of European Cities Stephen Platt

Causes of Urban Shrinkage: an overview of European cities Stephen Platt Reference: Platt S (2004) Causes of Urban Shrinkage: an overview of European cities. COST CIRES Conference, University of Amsterdam 16-18 February COST CIRES Conference, University of Amsterdam 16-18 February Causes of Urban Shrinkage: an overview of European cities Stephen Platt A number of interrelated factors contribute to or trigger urban shrinkage in European cities. In general there are three principal widespread structural causes of urban decline – economic, social and demographic change. Climate change may also come to play an increasingly role in migration, but to date environmental factors are not a significant cause of shrinkage. Secondary outcomes, for example the migration of young or highly skilled individuals, poorer service provision, regional specialisation or house price differentials, may exacerbate or contribute to further shrinkage. What might be considered a leading factor, however, and what is merely a consequence will depend on the particular case. There is also a scalar dimension at work. Economic restructuring is a global phenomenon and occurs all over the western world. Lower fertility is wide spread all over Europe, but suburbanisation is regional phenomenon. Interestingly the degree of shrinkage varies between cities in the same region and so cannot solely be explained by such macro factors as de- industrialisation and lower fertility. Local characteristics, for example policy initiatives, blurred property rights in the centre of some Eastern European cities, may also contribute to these different levels of shrinkage. Finally, a distinction should be made between the causes of shrinkage for different types and sizes of settlements. -

Evolution of Test Cricket in Last Six Decades a Univariate Time Series Analysis

Evolution of Test Cricket in Last Six Decades A Univariate Time Series Analysis Mayank Nagpal Sumit Mishra 1 Introduction We intend to analyse the structural changes in the average annual run-rate, i.e., how many runs are scored in each over, a measure of how much bat dominates the ball or how aggressively teams bat. Test cricket is the traditional format of the game. It is considered to be a snail-form of the game when we compare it with newer versions of the game, viz, ODI and T20 .A test cricket match lasting 5 days is apparently a lot less exciting for some than an ODI which lasts for eight hours or a T20 match which is matter of two-three hours. The general view is that with the advent of new technology, pitches that are more batsmen-friendly and craving for result in each game, the average run rate seems to have increased. Some analysts attribute this change to the emergence of newer formats and other innovations in the game. The question we are trying to answer is about whether these factors like those mentioned below had any significant impact on the game. The events whose effect we like to capture are: • Advent of One Day International(ODI):With dying popularity of test cricket matches during 1960s,a tournament called Gillette Cup was played in 1963 in England. The cup had sixty- five overs a side matches. This tourney was a knockout one and it became quite popular and laid foundation for a sleeker format of the game known as ODI-fifty overs a side game. -

The Malthusian Economy

The Malthusian Economy Economics 210a January 18, 2012 • Clark’s point of departure is the observation that the average person was no better off in 1800 than in 100,000 BC. – As Clark puts it on p.1. of his book, “Life expectancy was no higher in 1800 than for hunter-gatherers.” – Something changed after that of course. But this is for later in the course….. 2 • Clark’s point of departure is the observation that the average person was no better off in 1800 than in 100,000 BC. – How could he possibly know this? 3 Various forms of evidence, but first and foremost that on heights • There is little sign in modern populations of any genetically determined differences in potential stature, except for some rare groups such as the pygmies of Central Africa. • But nutrition does influence height. • In addition to the direct impact of nutrition on human development, episodes of ill health during growth phases can stop growth, and the body catches up only partially later on. And nutrition is an important determinant of childhood health. • As Clark puts it, “stature, a measure of both the quality of diet and of children’s exposure to disease, was [as high or] higher in the Stone Age than in 1800.” – This is a pretty striking observation. How are we to understand it? 4 The standard framework for doing so is the Malthusian model • Thomas Robert Malthus was born into a wealthy family in 1766, educated at Cambridge, and became a professor at Cambridge and eventually an Anglican parson. • His students referred to him as Pop Malthus (“Pop” for population). -

Reflection Very Long Range Global Population Scenarios to 2300 And

DEMOGRAPHIC RESEARCH VOLUME 28, ARTICLE 39, PAGES 1145-1166 PUBLISHED 30 MAY 2013 http://www.demographic-research.org/Volumes/Vol28/39/ DOI: 10.4054/DemRes.2013.28.39 Reflection Very long range global population scenarios to 2300 and the implications of sustained low fertility Stuart Basten Wolfgang Lutz Sergei Scherbov © 2013 Stuart Basten, Wolfgang Lutz & Sergei Scherbov. This open-access work is published under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial License 2.0 Germany, which permits use, reproduction & distribution in any medium for non-commercial purposes, provided the original author(s) and source are given credit. See http:// creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/2.0/de/ Table of Contents 1 Introduction 1146 2 Could global fertility levels fall to well below population 1147 replacement level? 3 Method 1151 4 Results 1152 5 Conclusions 1154 6 Acknowledgement 1156 References 1157 Appendix 1: Detailed results of alternative global population 1162 projections to 2300 Appendix 2: Input data, code and method of calculation 1165 Demographic Research: Volume 28, Article 39 Reflection Very long range global population scenarios to 2300 and the implications of sustained low fertility Stuart Basten1 Wolfgang Lutz2 Sergei Scherbov3 Abstract BACKGROUND Depending on whether the global level of fertility is assumed to converge to the current European TFR (~1.5) or that of Southeast Asia or Central America (~2.5), global population will either decline to 2.3-2.9 billion by 2200 or increase to 33-37 billion, if mortality continues to decline. Furthermore, sizeable human populations exist where the voluntarily chosen ideal family size is heavily concentrated around one child per woman with TFRs as low as 0.6-0.8. -

Wasted Catch: Unsolved Problems in U.S. Fisheries

© Brian Skerry WASTED CATCH: UNSOLVED PROBLEMS IN U.S. FISHERIES Authors: Amanda Keledjian, Gib Brogan, Beth Lowell, Jon Warrenchuk, Ben Enticknap, Geoff Shester, Michael Hirshfield and Dominique Cano-Stocco CORRECTION: This report referenced a bycatch rate of 40% as determined by Davies et al. 2009, however that calculation used a broader definition of bycatch than is standard. According to bycatch as defined in this report and elsewhere, the most recent analyses show a rate of approximately 10% (Zeller et al. 2017; FAO 2018). © Brian Skerry ACCORDING TO SOME ESTIMATES, GLOBAL BYCATCH MAY AMOUNT TO 40 PERCENT OF THE WORLD’S CATCH, TOTALING 63 BILLION POUNDS PER YEAR CORRECTION: This report referenced a bycatch rate of 40% as determined by Davies et al. 2009, however that calculation used a broader definition of bycatch than is standard. According to bycatch as defined in this report and elsewhere, the most recent analyses show a rate of approximately 10% (Zeller et al. 2017; FAO 2018). CONTENTS 05 Executive Summary 06 Quick Facts 06 What Is Bycatch? 08 Bycatch Is An Undocumented Problem 10 Bycatch Occurs Every Day In The U.S. 15 Notable Progress, But No Solution 26 Nine Dirty Fisheries 37 National Policies To Minimize Bycatch 39 Recommendations 39 Conclusion 40 Oceana Reducing Bycatch: A Timeline 42 References ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The authors would like to thank Jennifer Hueting and In-House Creative for graphic design and the following individuals for their contributions during the development and review of this report: Eric Bilsky, Dustin Cranor, Mike LeVine, Susan Murray, Jackie Savitz, Amelia Vorpahl, Sara Young and Beckie Zisser. -

One Day Limited Overs Cricket Matches Within the Province of Alberta Will Follow I.C.C

Cricket Alberta (CA) Playing Rules One day limited overs cricket matches within the Province of Alberta will follow I.C.C. rules, however, the following rules takes precedent: 1. Start of Match a. Matches shall start at the time set by the Executive of the respective League. b. If a team does not have 7 players present at the ground 15 minute prior to the scheduled match start, the other team shall be awarded the toss. c. If a team does not have 7 players present at the ground at the scheduled start time, it shall forfeit the match. The non-defaulting team shall be awarded a win. d. If a team delays the commencement of a match for any reason other than in 1(c), it shall be penalized by deducting 1 over from their batting quota for each 4 minutes of delay. 2. Length of Match a. All matches in the highest division of a league shall be 50 overs per team. For all other divisions, leagues have the right to adjust the number of overs. b. Both innings shall be completed on the same day. c. The break between innings shall be set by the leagues. d. A mandatory 5 minute water break is allowed per innings, but the break shall occur after one hour of playing time has elapsed. Other breaks may be given at the umpires’ discretion. e. No bowler shall bowl more than 1/5 of the number of overs allotted to each innings at the start of the first innings. 3. Time Limit a. -

Immigrant Population Decline Has Not Only Been Higher in the Past Twenty Years Than Any Other Year—It Is Even Higher in California (-6.2%) (See Table 1)

UC Merced Community and Labor Center Estimates Decline among US Immigrant Population Recent US Census Bureau data suggest the US immigrant population has experienced a sharp population decline (2.6%) since the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic. Figure 1. Change in US Immigrant Population, 2000-2020 Source: IPUMS-CPS Current Population Survey, Basic Monthly Survey, March-July 2000-2020 The UC Merced Community and Labor Center analyzed the US Census Bureau’s Current Population Survey- Basic Monthly Survey for 2000-2020.1 The decline in the US immigrant population in 2020 (-2.6%) is unprecedented in recent decades, even surpassing that during the Great Recession of 2008-2009 (-1.6%) (see figure 1). While some immigrants form the backbone of the workforce in essential industries such as agriculture or meatpacking, others have been displaced by the economic slowdown in service sector industries. A by the University of California Merced Community and Labor Center had found that California’s economic growth was among the slowest in the nation following the pandemic. Several of California’s industries had been hit particularly hard, such as the arts and entertainment, recreation, hotel and accommodations, and food services industries, where more than four in ten jobs were lost. 1 (The analysis was limited to the months that followed the onset of the pandemic, March to July). Table 1. Immigrant Population, US and California 2019-2020 2019 2020 Change Change % California 10,344,805 9,702,784 -642,021 -6.2% Non-California US 34,965,435 34,434,190 -531,246 -1.5% Total US 45,310,240 44,136,974 -1,173,266 -2.6% Source: IPUMS-CPS Current Population Survey, Basic Monthly Survey, March-July, 2000- 2020 The new analysis finds that immigrant population decline has not only been higher in the past twenty years than any other year—it is even higher in California (-6.2%) (see table 1). -

– the Game of Test Cricket Part 5

24 LIFE NEWSPAPERS IN EDUCATION sunshinecoastdaily.com.au Thursday, November 23, 2017 Catch this THE Baggy Green is the nickname given to the capeach 4 cricketer in the Aussie side wears on their head. A baggy PART green cap has been a part of the Australian test cricket NiE uniform since the early twentieth century. TERMS EQUIPMENT REQUIRED LIKE all sports, the game of cricket has its own set OTHER than the on field equipment of of rules. Knowing these HOWZAT stumps and bails, there are a few pieces of terms will help you equipment required to play the game. understand the game. ■ A ball average, bowling - The The ball used in cricket is a cork ball total of runs scored off a covered in leather, weighing between 155.9g bowler in the period to – THE GAME OF TEST and 163g. The two most common colours of which the average refers, cricket balls are red – used in Test cricket divided by the number of and First Class cricket, and white – used in wickets he took in that One Day matches. period. A proficient ■ A bat bowler will aim for an CRICKET Bats used in cricket are made of flat wood, average of less than 30. and connected to a conical handle. They are hat trick - Three wickets not allowed to be longer than 96.5cm and taken in successive TODAY the first ball will be bowled in the 2017/18 Test series have to be less than 10.8cm wide. While balls. A bowler who has there is no standard weight, most bats taken two successive between Australia and England at the Gabba cricket ground range between 1.2kg and 1.4kg.