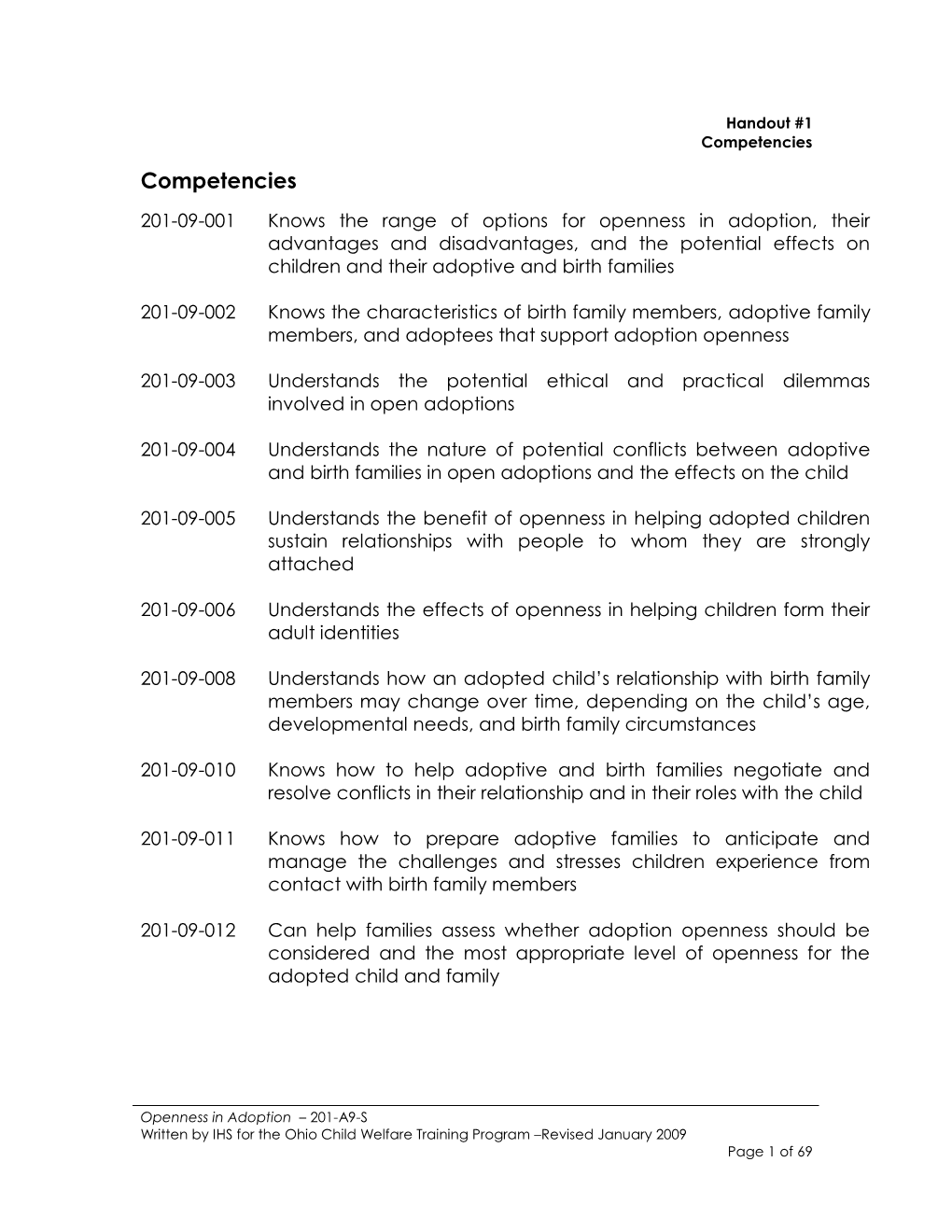

Competencies

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Separated at Adoption: Addressing the Challenges of Maintaining Sibling-Of-Origin Bonds in Post-Adoption Families

Scholarly Commons @ UNLV Boyd Law Scholarly Works Faculty Scholarship Winter 2015 Separated at Adoption: Addressing the Challenges of Maintaining Sibling-of-Origin Bonds in Post-adoption Families Rebecca L. Scharf University of Nevada, Las Vegas -- William S. Boyd School of Law Follow this and additional works at: https://scholars.law.unlv.edu/facpub Part of the Constitutional Law Commons, Family Law Commons, Juvenile Law Commons, and the Law and Psychology Commons Recommended Citation Scharf, Rebecca L., "Separated at Adoption: Addressing the Challenges of Maintaining Sibling-of-Origin Bonds in Post-adoption Families" (2015). Scholarly Works. 928. https://scholars.law.unlv.edu/facpub/928 This Article is brought to you by the Scholarly Commons @ UNLV Boyd Law, an institutional repository administered by the Wiener-Rogers Law Library at the William S. Boyd School of Law. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Separated at Adoption: Addressing the Challenges of Maintaining Sibling-of-Origin Bonds in Post- adoption Families REBECCA L. SCHARF* *Associate Professor of Law, William S. Boyd School of Law, University of Nevada, Las Vegas. B.A., Brandeis University, 1988. J.D., Harvard Law School, 1991. Thank you to Dean Dan Hamilton and the administration of the William S. Boyd School of Law for its tremendous support. Thanks as well to Mary Berkheiser, Jennifer Carr, Nancy Rapoport, and Karen Sneddon. I would also like to thank participants in the Rocky Mountain Junior Scholars Forum for their feedback on early drafts. 84 Winter 2015 SeparatedAt Adoption 85 I. Introduction Throughout the United States, for thousands of children languishing in foster care, adoption can seem like an unattainable fantasy; for the lucky few who are adopted, however, reality sets in when they first learn that their adoption has an unimaginable consequence. -

Issues in Adoption in Ireland

The Economic and Social Research Institute ISSUES IN ADOPTION IN IRELAND HAROLD j. ABRAMSON BROADSHEET NO. 93 JUL If, 1984 THE ECONOMIC AND SOCIAL RESEARCH INSTITUTE COUNCIL, 1983- 1984 *T. K. WHITAKER, M.SC.(ECON.), D.ECON., SC., LL.D., President of the Institute. *P. LYNCH. M.A., M.R.I.A., Chairman of the Council. R. D. C. BLACK, PH.D., Professor, Deportment of Economics, The Queen’s Univer.~ity, Belfast. °SEAN CROM I EN, B.A., Second Secretary, Department of b’inance. G. DEAN, M.D., F.R.C.P., Director, Medico-Social Research Board. N.J. GIBSON, B.SC.(ECON), PH.D., Professor, Department of Economics, New University of ULster. Coleraine. PATRICK A. HALL, B.E., M.S., DIP.STAT., Director of Research, In.ltitute of Public Administration. *W. A. HONOHAN, M.A., F.[.A. *KIERAN A. KENNEDY, M.ECON.SC., B.PHIL., PH.D., Director of the Institute. MICHAEL J. KILLEEN, B.A., B.COMM., LL.D., Chairman, Irish Distillers Group. T. P. L[NEHAN, B.E.,’ B.SC., Director, Central Statistics Office. *D. F. McALEESE, B.COMM., M.A., M.ECON.SC., PH.D., Whately Professor of Political Economy, Trinity College, Dublin. CHARLES McCARTHY, PH.D., B.L., Professor of lmtustrial Relations, "l~nity College, Dublin. *EUGENE McCARTHY, M.SC.(ECON.), D.ECON.SC., Director, Federated Union of Employers. JOHN j. McKAY, B.SC., D.P.A., B.COMM., M.ECON.SC., Chief Executive Officer. Co. Cavan Vocational Education Committee. *J. F. MEENAN, M.A., B.L. *D. NEVIN, General Secretary, Irish Congress of Trade Unio~ts. -

AMERICAN ADOPTION CONGRESS 32Nd Annual National Conference Registration and Information Book

Registration and Information Book AMERICAN ADOPTION CONGRESS 32nd Annual National conference Many Faces Of Adoption Wednesday, April 13 – Sunday, April 17, 2011 The Florida Hotel and Conference Center Orlando, Florida Wednesday, April 13 - Sunday, April 17, 2011 the florida hotel and conference center orlando, florida et a jump on spring and join us in Orlando for Gthe 32nd Annual AAC Conference, Many Faces of Adoption. April is a lovely time in Central Florida, with temperatures in the low 80s, sunshine and low humidity. The conference will include a unique blend of keynotes, workshops, film, performance and celebration. We hope you can join us. n Wednesday, April 13, 2011 we are offering special Oadmission to the Universal Orlando theme parks. The Islands of Adventure offers exciting roller coasters, 3D entertainment, and the new Wizarding World of cinemas, CityWalk is also host to a variety of concerts Harry Potter. At the Universal Studio Florida you will and special events throughout the year. The conference go behind the scenes, beyond the screen, and jump right opens on Wednesday evening with Making the Most of into the action of your favorite movies at the number one the Conference Experience, followed by a performance movie and TV based theme park in the world. You can of BLANK by Brain Stanton. reserve your ticket when you register for the conference. Not into theme parks? You can take our bus to Universal he Florida Hotel and Conference Center is located CityWalk, for dinner and shopping. As popular with locals Twithin the Florida Mall, with many dining options as it is with visitors, this 30-acre entertainment complex at all price points within close walking distance. -

OPEN VS. CLOSED ADOPTION Social Work and Jewish Law Perspectives

OPEN VS. CLOSED ADOPTION Social Work and Jewish Law Perspectives MOSHE A. BLEICH, MSW, CSW Social Worker, Madeleine Borg Community Services, Jewish Board of Family and Childrens Services, New York Adoption involves a process of severing ties with a biological family and creating new ones with an adopting family. Closed adoption is designed to eradicate those ties completely and to allow a child to live as if he or she were the natural child of the adoptive parent Open adoption prevents that suppression of the original ties. Adopted children are increasingly seeking access to their genealogical history. Jewish tradition does not sanction the suppression of parental identity. The result is a strong bias in favor of open adoption. Religious teaching governing conduct between men and women underscores the distinction between natural and adoptive families. For purposes of effective therapy, those cultural factors must be recognized in assessing problems and may also be harnessed in effecting a positive therapeutic outcome. OPEN VERSUS CLOSED ADOPTION legal rights equal to those of natural children. As a corollary, adoptive parents felt that they T^he institution of adoption, of voluntarily should exercise total control over the welfare A raising a child of other parents as one's of the adopted child and that the child's ties own, has existed since antiquity. In relatively to his biological parents should be severed. modern times, in the late nineteenth and early This line of argument complements Ryburn's twentieth centuries as adoption procedures analysis (1990, p. 21) that adoption legisla were developed in the United States, it be tion was designed to achieve a legal fiction, came common practice to seal adoption an attempt to extinguish all ties to birth records. -

A Study of Muslim Economic Thinking in the 11Th A.H

Munich Personal RePEc Archive A study of Muslim economic thinking in the 11th A.H. / 17th C.E. century Islahi, Abdul Azim Islamic Economics Institute, King Abdulaziz University, Jeddah, KSA 2009 Online at https://mpra.ub.uni-muenchen.de/75431/ MPRA Paper No. 75431, posted 06 Dec 2016 02:55 UTC Abdul Azim Islahi Islamic Economics Research Center King Abdulaziz University Scientific Publising Centre King Abdulaziz University P.O. Box 80200, Jeddah, 21589 Kingdom of Saudi Arabia FOREWORD There are numerous works on the history of Islamic economic thought. But almost all researches come to an end in 9th AH/15th CE century. We hardly find a reference to the economic ideas of Muslim scholars who lived in the 16th or 17th century, in works dealing with the history of Islamic economic thought. The period after the 9th/15th century remained largely unexplored. Dr. Islahi has ventured to investigate the periods after the 9th/15th century. He has already completed a study on Muslim economic thinking and institutions in the 10th/16th century (2009). In the mean time, he carried out the study on Muslim economic thinking during the 11th/17th century, which is now in your hand. As the author would like to note, it is only a sketch of the economic ideas in the period under study and a research initiative. It covers the sources available in Arabic, with a focus on the heartland of Islam. There is a need to explore Muslim economic ideas in works written in Persian, Turkish and other languages, as the importance of these languages increased in later periods. -

Your Decision: Suggestions for Birthmothers Considering an Adoption Plan Megan Lindsey

Your Decision: Suggestions for Birthmothers Considering an Adoption Plan Megan Lindsey Introduction Is Adoption For Me? Facing an unintended pregnancy has the There are many questions to consider when facing potential to leave women1 or couples frightened an unintended pregnancy. Below are some of and confused. If you are facing an unintended the different questions birthmothers ask about pregnancy, you deserve accurate information adoption, and some resources to help you better about all of your options, compassionate support, understand the adoption process as you consider and the space to make your own decisions. The whether it is the right option for you. information presented here is intended to help Whose Decision Is it to Make you understand the option of adoption, help an Adoption Plan? you consider whether adoption is for you, and provide some suggestions that will help to ensure The decision to make an adoption plan belongs a positive experience should you choose to make to you—the birthparents. While support systems an adoption plan. consisting of family members and friends can be helpful and important to help you think things What is Adoption? through, ultimately the decision belongs only to the birthparents. Both the birthmother and If you make an adoption plan, you are deciding birthfather have the right to be involved in this that someone else will parent your child after he important decision. Birthfathers have the right to or she is born. Adoption is the legal process by be notified if a child has been conceived and an which all parental rights and responsibilities are adoption plan is being made. -

Adoptions KEVIN W

Obtaining Information About Adoptions KEVIN W. DUNN COUNTY OFFICES MEDINA COUNTY Probate Court PROBATE COURT JUDGE 93 Public Square, Room 102 Medina, Ohio 44256 (330) 725-9703 Job and Family Services ADOPTIONS 232 Northland Drive ADOPTIONS Medina, Ohio 44256 (330) 722-9283 JUDGE KEVIN W. DUNN Medina County Bar Association MEDINA COUNTY PROBATE COURT 93 Public Square JUDGE Medina, Ohio 44256 (330) 725-9744 (for referral to an attorney who specializes Dear Friend— in adoption law) My policy is to fulfill the Probate Court PRIVATE AGENCIES duties efficiently and effectively. If you Private Adoption Agencies have any questions or you need more (licensed by the State of Ohio) information on a Probation Court STATE AGENCIES matter, please contact my office. Bureau of Vital Statistics We are here to serve you. I hope your Ohio Department of Health experience in my court is helpful and 246 North High Street informative. P.O. Box 15098 Medina County Probate Court Columbus, Ohio 43215-0098 Judge Kevin W. Dunn 93 Public Square Ohio Putative Father Registry Medina County Probate Court Medina, OH 44256 255 East Main Street, Third Floor Columbus, Ohio 43215 Phone: (330) 725-9703 Ohio Department of Human Services Monday—Friday 255 East Main Street 8:00 AM—4:30 PM Columbus, Ohio 43215 Check your telephone book if an address or telephone number is not listed above. ABOUT THIS PAMPHLET FREQUENTLY ASKED QUESTIONS This publication is designed as service to the public to provide an understanding of the duties and procedures of Who May Adopt? Must I Have an Attorney? 1. -

Openness in International Adoption

Texas A&M University School of Law Texas A&M Law Scholarship Faculty Scholarship 3-2015 Openness in International Adoption Malinda L. Seymore Texas A&M University School of Law, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.tamu.edu/facscholar Part of the Family Law Commons, and the International Law Commons Recommended Citation Malinda L. Seymore, Openness in International Adoption, 46 Colum. Hum. Rts. L. Rev. 163 (2015). Available at: https://scholarship.law.tamu.edu/facscholar/707 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Texas A&M Law Scholarship. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty Scholarship by an authorized administrator of Texas A&M Law Scholarship. For more information, please contact [email protected]. OPENNESS IN INTERNATIONAL ADOPTION Malinda L. Seymore* ABSTRACT After a long history of secrecy in domestic adoption in the United States, there is a robust trend toward openness. That is, however, not the case with internationaladoption. The recent growth in international adoption has been spurred, at least in part, by the desire of adoptive parents to return to closed, confidential adoptions where the identity of the birth mother is secret and there is no ongoing contact with her. There is, however, an emergent interest in increased openness in internationaladoption, spurred by the success of domestic open adoptions, health concerns when an adoptee's genetic history is important, psychological issues relating to identity in adoptees, and concern that the international adoption might have been corrupt. International adoptive families who were once happy to avoid birth parent involvement have begun to seek them out. -

Download&File Srl= 4182&Sid=D28b7e0aaa719923304c1a0afe05a569

Samford University From the SelectedWorks of David M. Smolin Spring 2012 OF ORPHANS AND ADOPTION, PARENTS AND THE POOR, EXPLOITATION AND RESCUE: A SCRIPTURAL AND THEOLOGICAL CRITIQUE OF THE EVANGELICAL CHRISTIAN ADOPTION AND ORPHAN CARE MOVEMENT David M. Smolin Available at: http://works.bepress.com/david_smolin/10/ OF ORPHANS AND ADOPTION, PARENTS AND THE POOR, EXPLOITATION AND RESCUE: A SCRIPTURAL AND THEOLOGICAL CRITIQUE OF THE EVANGELICAL CHRISTIAN ADOPTION AND ORPHAN CARE MOVEMENT David M. Smolin* The evangelical Christian 1 movement within the United States has become mobilized and focused on adoption and orphan care as a Christian imperative and practice over the last several years. 2 This mobilization and practice has been accompanied by scriptural and the- ________________________ * Harwell G. Davis Professor of Constitutional Law; Director, Center for Biotechnology, Law, and Ethics, Cumberland Law School, Samford University. I want to thank Desiree Smolin and acknowledge her intellectual influence, as we have worked together in analyzing adoption. I also want to thank Laura Cunliffe, Hannah Garner, Peter Gong, Craig Lawrence, Brie Stanley, and Olivia Woodard for their research assistance, and Greg Laughlin, Mark Gignilliat, Ken Matthews, Becca McBride, Sydney Park, and Desiree Smolin for their review of and comments on prior drafts of this essay. I also want to thank Nathan Smolin for his assistance with Greek and Latin translation issues, and Doug Clapp for assistance with identifying classical sources. I also want to thank the many other individuals who shared their experiences and perspectives or otherwise commented on this article or topics related to this article, as well as those who attended my 2012 ASAC conference presentation related to this topic. -

Adoption Overview

July 2013 ALSP Law Series ADOPTION OVERVIEW What is an Adoption? What is the Process of Adoption? Adoption is when someone other than the biological The adoption process varies depending on the type of parent of a child assumes legal responsibility for the adoption. So does the length of time that it takes. child. The adopted child is granted the same inheritance Typically, though, a private-agency adoption will move rights as a biological child. faster. Who May Be Adopted? The adoption process may include the following: Anyone. Even an adult can be adopted. But either the 1. Petition for Adoption: The person seeking parent or the adopted child must be an Arkansas resident the adoption must file a petition with the in order to adopt in Arkansas. clerk of the court. 2. Consent or Waiver of Consent: The adoption Who May Adopt? may be granted only if the natural mother and Generally, the following people may adopt someone father consent to it. But the court may decide else: their consent is not required. This could happen, • A husband and wife together although one or for example, if a court has terminated their both are minors. parental rights. It also could happen if the • An unmarried adult. parents have abandoned or not supported the • The unmarried father or mother of the individual child for more than 1 year. to be adopted. 3. Sworn Affidavit: The petitioner must file an affidavit detailing expenses or payments related • A married person without the other spouse joining as a petitioner. An adoption by a step- to the adoption. -

Evidence- Based Care Sheet

EVIDENCE- Open Adoption BASED CARE SHEET What We Know › Adoption is the permanent, legal transfer of parental rights and responsibilities from birth parents (BPs) to adoptive parents (APs), with the goal of ensuring that children whose BPs are unwilling or unable to care for them have a legal family to nurture and support them.(22,30) Adoption is also understood to be a lifelong process involving complex, dynamic relationships between children, their biological families, and their adoptive families that take place in the context of their communities and cultures(9,19) • Adoptions may be independent/private (i.e., BPs make voluntary adoption plans for their children, most often during infancy), through a public agency (i.e., state or county social service departments make adoption plans for children in foster care when BPs are unable to provide a safe home and their parental rights have been terminated), or intercountry (i.e., adoption of children from other countries)(1) › During much of the 20th century, adoption in many Western countries involved a high degree of confidentiality and secrecy, which was designed to protect those involved from the stigma associated with birth to unmarried women and with infertility, as well as to prevent BPs from intruding in the adoptive family. Over the past several decades, however, adoption practice has increasingly shifted toward more openness, both in the sharing of information with children and in the amount of contact between members of the adoption triad (i.e., BPs, APs, and adopted children)(29) -

NM's People of the Year

Ogo Mobility Device Artist Richard Bell Adoption Options life beyond wheels Wheeling Forward: NM’s People of the Year Alex Elegudin & Yannick Benjamin newmobility.com JAN 2018 $4 DO YOU HAVE A RELIABLE SOLUTION TO YOUR BOWEL PROGRAM? Use CEO-TWO® Laxative Suppositories as part of CEO-TWO works reliably within 30 minutes. These your bowel program. These unique CO2-releasing unique suppositories are even self-lubricating, suppositories allow you to control your bowel making their use as easy and convenient as possible. function and prevent constipation and related problems, such as autonomic dysreflexia. Regain • 3 year shelf life confidence in social and work situations by • Reduces bowel program time to under 30 minutes avoiding embarrassing accidents with CEO-TWO! • Water-soluble formula • Does not cause mucous leakage Many laxatives and suppositories are not reliable • Self-lubricating and are unpredictable. Having secondary bowel • No refrigeration necessary movements when you least expect it with such • Individually wrapped and easy to open products is not at all uncommon. • Unique tapered shape makes retention easier, providing satisfactory results every time ORDERING INFORMATION: Box of 2 suppositories ...............NDC #0283-0808-11 ORDER BY PHONE ORDER ONLINE Box of 6 suppositories ...............NDC #0283-0808-36 1-800-238-8542 www.amazon.com Box of 12 suppositories .............NDC #0283-0808-12 M-F: 8:00 a.m. – 4:30 p.m. ET Box of 54 suppositories .............NDC #0283-0808-54 LLC CEO-TWO is a registered trademark of Beutlich® Pharmaceuticals, LLC. CCA 469 1114 THE 4FRONT TM OF A NEW ERA “I have been using a wheelchair for 35 years now – all different types – and the 4Front is by far the most advanced, comfortable and maneuverable chair I have ever driven.” – Stewart Lundy “The most advanced, comfortable and maneuverable chair...ever!” Take the 4Front TM challenge and test drive one today.