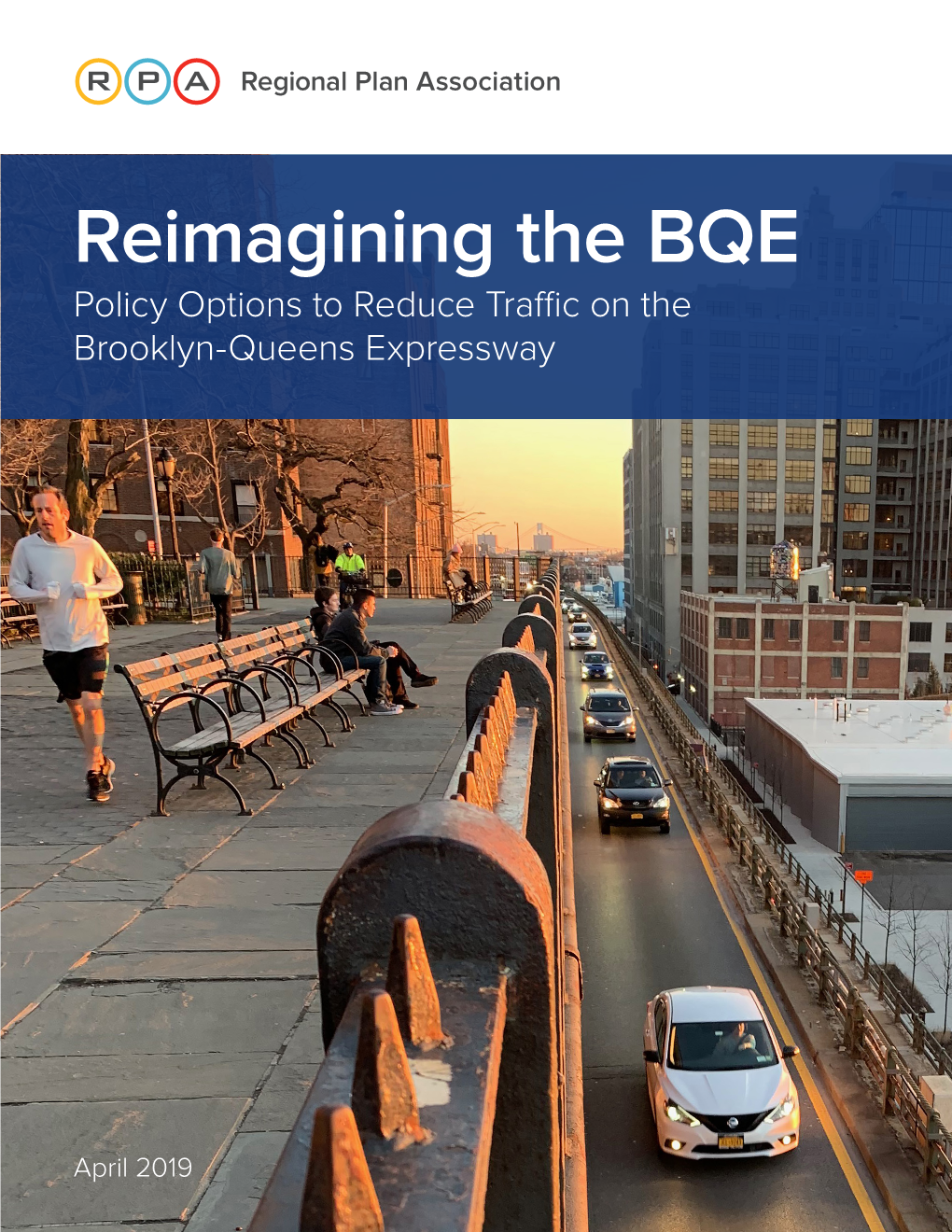

Reimagining the BQE Policy Options to Reduce Traffic on the Brooklyn-Queens Expressway

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Induced Demand: an Urban and Metropolitan Perspective

Induced Demand: An Urban and Metropolitan Perspective Robert Cervero, Professor Department of City and Regional Planning University of California Berkeley, California E-Mail: [email protected] Paper prepared for Policy Forum: Working Together to Address Induced Demand U.S. Environmental Protection Agency Federal Highway Administration, U.S. Department of Transportation Eno Transportation Foundation, Incorporated March 2001 Second Revision Induced Demand: An Urban and Metropolitan Perspective Most studies of induced travel demand have been carried out at a fine to medium grain of analysis – either the project, corridor, county, or metropolitan levels. The focus has been on urban settings since cities and suburbs are where the politics of road investments most dramatically get played out. The problems assigned to induced demand – like the inability to stave off traffic congestion and curb air pollution – are quintessentially urban in nature. This paper reviews, assesses, and critiques the state-of-the-field in studying induced travel demand at metropolitan and sub-metropolitan grains of analysis. Its focus is on empirical and ex post examinations of the induced demand phenomenon as opposed to forecasts or simulations. A meta-analysis is conducted with an eye toward presenting an overall average elasticity estimate of induced demand effects based on the best, most reliable research to date. 1. URBAN HIGHWAYS AND TRAVEL: THE POLICY DEBATE Few contemporary issues in the urban transportation field have elicited such strong reactions and polarized political factions as claims of induced travel demand. Highway critics charge that road improvements provide only ephemeral relief – within a few year’s time, most facilities are back to square one, just as congested as they were prior to the investment. -

Annual Report Power Breakfasts

2017 Annual Report Power Breakfasts 2017’s Power Breakfast season included a diverse array of leaders from New York City and State, resulting in substantive and timely policy discussions. We welcomed the Governor, the Mayor, the Attorney General, and thought leaders on education, economics and transportation infrastructure. JANUARY 4, 2017 On January 4th, Governor Cuomo invited a panel including Department of Transportation Commissioner, Matthew Driscoll, President of the Metropolitan Transit Authority, Tom Prendergast, and Chairman of the Airport Master Plan Advisory Panel, Daniel Tishman, to present a plan to revamp the terminal, highways, and public transit leading to John F. Kennedy Airport. JANUARY 26, 2017 University Presidents Panel On January 26th leaders of some of New York City’s Universities convened to talk about the role of applied sciences in the future of higher education and how it will be used to cultivate the future work force. The panel was moderated by 1776’s Rachel Haot and included Lee C. Bollinger, President, Columbia University; Andrew Hamilton, President, New York University; Dan Huttenlocher, Dean and Vice Provost, Cornell Tech; Peretz Lavie, President, Technion - Israel Institute of Technology; and James B. Milliken, Chancellor, CUNY. MARCH 15, 2017 Budget Analysis Panel On March 15th, ABNY invited a panel of budget experts to discuss the potential impact of proposed federal policies on the New York City budget and overall economy. The panel was moderated by Maria Doulis, Vice President, Citizens Budget Commission; and the panelists included Dean Fuleihan, Director, Mayor’s Office of Management and Budget; Latonia McKinney, Director, NYC Council Finance Division; Preston Niblack, Deputy Comptroller, Office of City Comptroller; and Kenneth E. -

The Fundamental Law of Road Congestion: Evidence from US Cities

University of Pennsylvania ScholarlyCommons Real Estate Papers Wharton Faculty Research 10-2011 The Fundamental Law of Road Congestion: Evidence From US Cities Gilles Duranton University of Pennsylvania Matthew A. Turner Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.upenn.edu/real-estate_papers Part of the Economics Commons, and the Real Estate Commons Recommended Citation Duranton, G., & Turner, M. A. (2011). The Fundamental Law of Road Congestion: Evidence From US Cities. American Economic Review, 101 (6), 2616-2652. http://dx.doi.org/10.1257/aer.101.6.2616 This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. https://repository.upenn.edu/real-estate_papers/3 For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Fundamental Law of Road Congestion: Evidence From US Cities Abstract We investigate the effect of lane kilometers of roads on vehicle-kilometers traveled (VKT) in US cities. VKT increases proportionately to roadway lane kilometers for interstate highways and probably slightly less rapidly for other types of roads. The sources for this extra VKT are increases in driving by current residents, increases in commercial traffic, and migration. Increasing lane kilometers for one type of road diverts little traffic omfr other types of road. We find no evidence that the provision of public transportation affects VKT. We conclude that increased provision of roads or public transit is unlikely to relieve congestion. Disciplines Economics | Real Estate This journal article is available at ScholarlyCommons: https://repository.upenn.edu/real-estate_papers/3 American Economic Review 101 (October 2011): 2616–2652 http://www.aeaweb.org/articles.php?doi 10.1257/aer.101.6.2616 = The Fundamental Law of Road Congestion: Evidence from US Cities† By Gilles Duranton and Matthew A. -

Star Chef Preps Recipe to Address Jobs Crisis How Not to Save a B'klyn

INSIDE MLB’s FAN CAVE Social-media mavens score one for the game CRAIN’S® NEW YORK BUSINESS P. 25 VOL. XXX, NO. 18 WWW.CRAINSNEWYORK.COM MAY 5-11, 2014 PRICE: $3.00 NY’s new arts nexus Move over, Brooklyn: Queens is rising fast on city culture scene BY THERESA AGOVINO The Queens Theatre’s walls are lined with photos of the 1964-65 World’s Fair, a nod to the building’s genesis as part of the New York State Pavilion. Plays inspired by the World’s Fairs of 1939 and 1964— each held in Flushing Meadows Corona Park—are on tap for this summer. The theater’s managing director,Taryn Sacra- mone, is hoping nostalgia and curiosity about the fairs draw more people to the institution as she tries to raise its profile. STAGING A REVIVAL: Managing Director Taryn Momentum is on her side because Sacramone is seeking Queens is on a cultural roll. Ms. Sacramone’s new programming for See QUEENS on Page 23 the Queens Theatre. buck ennis How not to save a B’klyn hospital Star chef preps recipe Unions, activists, de Blasio fought to stop But the two opponents were in to address jobs crisis court on Friday only because com- LICH’s closure. Careful what you wish for munity groups, unions and politi- cians with little understanding of Each week, the French chef has Hospital in Cobble Hill, faced off New York’s complex health care in- So many restaurants, between 10 to 30 job openings in his BY BARBARA BENSON in a Brooklyn courtroom late last dustry have, for the past year, inject- too few workers; seven restaurants and catering busi- Friday. -

SCNY19 Smart Cities New York 2019

#SCNY19 Smart Cities New York 2019 MAY 13 AT CORNELL TECH MAY 14-15 AT PIER 36 For more information on the SCNY19 speakers please check: smartcitiesny.com/speakers 9:00 AM - 10:15 AM 12:15 PM - 1:45 PM 3:30 PM - 5:00 PM ROOM #161 ROOM #161 C40 CITIES ENCOURAGING CLIMATE ENLIGHTENED INFRASTRUCTURE ROOM #161 CITIES, SENSORS, AND SPATIAL INNOVATION IN THE PRIVATE SECTOR FOR SMARTER CITIES COMPUTING C40 Cities CNIguard RLAB ROOM #165 BUILD YOUR OWN SAFE SELF- ROOM #165 ROOM #165 DRIVING AI UNIVERSAL BASIC INCOME, LOCAL AGRICULTURE: PATHWAYS AlphaDrive SERVICES AND ASSETS - URBAN TO URBAN RESILIENCE IMPLICATIONS OF THE NEXT ERA WELLBEING Agritecture Consulting AND UBXs ROOM #061 NYCX MOONSHOTS: HOW NEW Demos Helsinki YORK CITY MAKES BIG BETS ON EMERGING ROOM #061 SMART INFRASTRUCTURE TECHNOLOGY OPPORTUNITY IDENTIFICATION ROOM #071 NYC Mayor’s Office of the Chief Technology Office PREPARING YOUR PEOPLE FOR THE Mott MacDonald Digital Ventures – Smart Infrastructure COMING OF THE ROBOTS Intelligent Community Forum ROOM #071 ROOM #071 INTERNATIONAL SMART CITY UNLOCKING THE POTENTIAL COLLABORATION: SCALING-UP IN AN OF THE CIRCULAR ECONOMY IN CITIES: 13TH MAY ROOM #091 KNOWLEDGE, CHALLENGES AND SOLUTIONS SUCCEEDING IN BUSINESS IN EMERGING ECOSYSTEM FROM AMSTERDAM AMERICA Kingdom of The Netherlands General Consulate of the Republic of Kosovo in New York Kingdom of The Netherlands Global Futures Group ROOM #091 Empire Global Ventures INCLUSION FOR ALL AND SMART ROOM #091 CITIES JOSEP LLUÍS SERT: FOOTPRINT ON K. Lisa Yang and Hock E. Tan Institute on Employment and Disability ROOSEVELT ISLAND and Jacobs Technion-Cornell Institute, Cornell Tech Farragut Fund for Catalan Culture in the U.S. -

Effective Strategies for Congestion Management

EFFECTIVE PRACTICES FOR CONGESTION MANAGEMENT: FINAL REPORT Requested by: American Association of State Highway and Transportation Officials (AASHTO) Prepared by: Cambridge Systematics, Inc. Cambridge, MA Resource Systems Group, Inc. Burlington, VT November 2008 The information contained in this report was prepared as part of NCHRP Project 20-24(63), National Cooperative Highway Research Program, Transportation Research Board. Acknowledgements This study was requested by the American Association of State Highway and Transportation Officials (AASHTO), and conducted as part of National Cooperative Highway Research Program (NCHRP) Project 20-24. The NCHRP is supported by annual voluntary contributions from the state Departments of Transportation (DOTs). Project 20-24 is intended to fund studies of interest to the leadership of AASHTO and its member DOTs. Christopher Porter of Cambridge Systematics was the lead author of the report, working with John Suhrbier of Cambridge Systematics and Peter Plumeau and Erica Campbell of Resource Systems Group. The work was guided by a task group chaired by Constance Sorrell which included Daniela Bremmer, Mara Campbell, Ken De Crescenzo, Eric Kalivoda, Ronald Kirby, Sheila Moore, Michael Morris, Janet Oakley, Gerald Ross, Steve Simmons, Dick Smith, Kevin Thibault, Mary Lynn Tischer, and Robert Zerrillo. The project was managed by Andrew C. Lemer, Ph. D., NCHRP Senior Program Officer. Disclaimer The opinions and conclusions expressed or implied are those of the research agency that performed the research and are not necessarily those of the Trans- portation Research Board or its sponsors. The information contained in this document was taken directly from the submission of the author(s). This docu- ment is not a report of the Transportation Research Board or of the National Research Council. -

Long Island Sound Waterborne Transportation Plan Task 2 – Baseline Data for Transportation Plan Development

Long Island Sound Waterborne Transportation Plan Task 2 – Baseline Data for Transportation Plan Development final memorandum prepared for New York Metropolitan Transportation Council Greater Bridgeport Regional Planning Agency South Western Regional Planning Agency prepared by Cambridge Systematics, Inc. with Eng-Wong Taub & Associates Howard/Stein-Hudson Associates, Inc. Gruzen Samton Architects, Planners & Int. Designers HydroQual Inc. M.G. McLaren, PC Management and Transportation Associates, Inc. STV, Inc. September 30, 2003 www.camsys.com final technical memorandum Long Island Sound Waterborne Transportation Plan Task 2 – Baseline Data for Transportation Plan Development prepared for New York Metropolitan Transportation Council Greater Bridgeport Regional Planning Agency South Western Regional Planning Agency prepared by Cambridge Systematics, Inc. 4445 Willard Avenue, Suite 300 Chevy Chase, Maryland 20815 with Eng-Wong Taub & Associates Howard/Stein-Hudson Associates, Inc. Gruzen Samton Architects, Planners & Int. Designers HydroQual Inc. M.G. McLaren, PC Management and Transportation Associates, Inc. STV, Inc. September 30, 2003 Long Island Sound Waterborne Transportation Plan Technical Memorandum for Task 2 Table of Contents 1.0 Introduction.................................................................................................................... 1-1 1.1 Purpose and Need.................................................................................................. 1-1 1.2 The National Policy Imperative .......................................................................... -

The Art and Science of Data-Driven Journalism

The Art and Science of Data-driven Journalism Executive Summary Journalists have been using data in their stories for as long as the profession has existed. A revolution in computing in the 20th century created opportunities for data integration into investigations, as journalists began to bring technology into their work. In the 21st century, a revolution in connectivity is leading the media toward new horizons. The Internet, cloud computing, agile development, mobile devices, and open source software have transformed the practice of journalism, leading to the emergence of a new term: data journalism. Although journalists have been using data in their stories for as long as they have been engaged in reporting, data journalism is more than traditional journalism with more data. Decades after early pioneers successfully applied computer-assisted reporting and social science to investigative journalism, journalists are creating news apps and interactive features that help people understand data, explore it, and act upon the insights derived from it. New business models are emerging in which data is a raw material for profit, impact, and insight, co-created with an audience that was formerly reduced to passive consumption. Journalists around the world are grappling with the excitement and the challenge of telling compelling stories by harnessing the vast quantity of data that our increasingly networked lives, devices, businesses, and governments produce every day. While the potential of data journalism is immense, the pitfalls and challenges to its adoption throughout the media are similarly significant, from digital literacy to competition for scarce resources in newsrooms. Global threats to press freedom, digital security, and limited access to data create difficult working conditions for journalists in many countries. -

8-25-20 MTA Transcript

NEW YORK STATE LEGISLATURE JOINT PUBLIC HEARING SENATE STANDING COMMITTEE ON TRANSPORTATION SENATE STANDING COMMITTEE ON CORPORATIONS, AUTHORITIES & COMMISSIONS ASSEMBLY STANDING COMMITTEE ON CORPORATIONS, AUTHORITIES & COMMISSIONS IMPACT OF COVID-19 ON THE METROPOLITAN TRANSPORTATION AUTHORITY August 25, 2020 10:00 a.m. - 3:30 p.m. Page 2 Joint Hearing Impact of COVID-19 on MTA, 8-25-20 SENATORS PRESENT: SENATOR LEROY COMRIE, Chair, Senate Standing Committee on Corporations, Authorities and Commissions SENATOR TIM KENNEDY, Chair, Senate Standing Committee on Transportation SENATOR TODD KAMINSKY SENATOR GUSTAVO RIVERA SENATOR ANNA KAPLAN SENATOR JESSICA RAMOS SENATOR ANDREW GOUNARDES SENATOR LUIS SEPULVEDA SENATOR THOMAS O’MARA SENATOR JOHN LIU SENATOR BRAD HOYLMAN SENATOR SHELLEY MAYER SENATOR MICHAEL RANZENHOFER SENATOR SUE SERINO Geneva Worldwide, Inc. 256 West 38t h Street, 10t h Floor, New York, NY 10018 Page 3 Joint Hearing Impact of COVID-19 on MTA, 8-25-20 ASSEMBLY MEMBERS PRESENT: ASSEMBLY MEMBER AMY PAULIN, Chair, Assembly Standing Committee on Corporations, Authorities and Commissions ASSEMBLY MEMBER KENNETH BLANKENBUSH ASSEMBLY MEMBER CHARLES FALL ASSEMBLY MEMBER NILY ROZIC ASSEMBLY MEMBER SANDRA GALEF ASSEMBLY MEMBER STEVEN OTIS ASSEMBLY MEMBER RON KIM ASSEMBLY MEMBER STACEY PHEFFER AMATO ASSEMBLY MEMBER VIVIAN COOK ASSEMBLY MEMBER DAVID BUCHWALD ASSEMBLY MEMBER PHILLIP PALMESANO ASSEMBLY MEMBER ROBERT CARROLL ASSEMBLY MEMBER REBECCA SEAWRIGHT ASSEMBLY MEMBER CARMEN DE LA ROSA ASSEMBLY MEMBER YUH-LINE NIOU Geneva Worldwide, -

A FORK in the ROAD a New Direction for Congestion Management in Sydney

A FORK IN THE ROAD A new direction for congestion management in Sydney COMMITTEE FOR SYDNEY ISSUES PAPER 12 APRIL 2016 INTRODUCTION The Committee for Sydney believes there is an urgent need for a better civic dialogue about transport options in Sydney. With notable exceptions,1 the current debate appears to be too polarised, ideological and mode-led, characterised more by heat than light. There is a need for a cooler, more evidence-based approach and a recognition that cities are complex and multi-faceted and no one transport mode will meet all needs. That approach brings challenges for government agencies and the community. For government agencies, it means having robust and transparent appraisal methods for selecting one transport mode or policy over another, and a respect for the concerns of communities affected by significant infrastructure projects. For communities, it means accepting necessary change when the broader public benefits have been shown. Addressing congestion must be part of this. But we must also not lose sight of the objective: reducing congestion means commuters in Sydney will spend less time stuck in traffic – and more time with family and contributing to our city. This has significant economic benefit for the city and for the community. In our view, Sydneysiders will support whatever transport mode or intervention is shown to be required to meet the city’s needs. But they will expect that the appraisal process used is mode-neutral, transparent and evidence-based, resulting in transport projects or interventions which deliver maximum public benefit and the best strategic outcomes for Sydney. -

Community Harlem News “Good News You Can Use”

Community Harlem News “Good News You Can Use” Vol. 13 No. 50 December 12 - 18, 2013 FREE The Harlem News Group, Inc. Connecting Harlem, Queens, Brooklyn and The South Bronx Steve Harvey and Judges Select Next Class of Disney Dreamers Academy Students page 10 . Jacob Soul Food Restaurant Gives Back - Free Dinners on Thanksgiving Day page 10 NELSON MANDELA - 1918-2013 Mayor Bloomberg Announces HE CHANGED OUR WORLD Country’s Largest Continuous Free page 17 Public WiFi Network Covering 95 City Community Calendar of Events page 8 Blocks in Harlem face/harlemnewsinc page 3 visit our website: www.harlemnewsgroup.com @harlemnewsinc Harlem News Group COMMUNITY HARLEM . QUEENS . BROOKLYN . BRONX Community HARLEM NEWS Community BROOKLYN NEWS Advertise Community BRONX NEWS Community Today QUEENS NEWS Free copies distributed in your community weekly “GOOD NEWS YOU CAN USE” IN THIS ISSUE: Community page 3 Editorial page 6 Real Estate page 7 Calendar page 8 Pat Stevenson Events page 9 A NOTE FROM THE PUBLISHER Holiday page 12 Health page 13 Good News You Can Use! Tribute page 17 The World mourns the death of Nel- Lifestyle page 19 Literary Corner page 20 son Mandela, while simultaneously celebrat- Urbanology page 21 ing his legacy. The Apollo marquee was Church page 22 scripted with his memory within hours of his Technology page 23 Classified page 24 passing. Peter Cooper spoke with individuals Crossword Puzzle page 26 who actually met Mr. Mandela and have had a Games/Horoscope page 27 relationship over the years in the tribute we present in this issue.. (see page 17) Publisher/Editor Pat Stevenson Film/Entertainment Roberto Johnson Since its opening in 2008, Jacobs A&E Editor Linda Armstrong Restaurant has graciously opened its doors Art & Cultural Stacey Ann Ellis Adams Report Audrey Adams and provided free dinners from its menu of Travel Editor Audrey Bernard more than 42 items on Thanksgiving day. -

Metropolitan Transportation Sustainability Advisory Workgroup

REPORT Metropolitan Transportation Sustainability Advisory Workgroup December 2018 Table of Contents Cover Letter .................................................................................................3 Executive Summary...................................................................................4 Introduction: The Transit Crisis...............................................................7 Recommendation on Governance Reform………… ...................9 Unsustainable Growth in Operating and Capital Costs ...................11 Recommendations on Cost and Operations ............................14 Recommendation on Intergovernmental Coordination ........20 Other Recommendations ..............................................................22 Sustainable Funding Options .................................................................25 Conclusion ...................................................................................................30 Appendices ..................................................................................................31 Metropolitan Transportation Sustainability Advisory Workgroup Report 2 December 18, 2018 Workgroup Members Hon. Michael Benedetto Hon. Fernando Ferrer Hon. Michael Gianaris Rhonda Herman Dear Governor Andrew Cuomo, Assembly Speaker Carl Heastie, Hon. Melissa Mark-Viverito Senate Majority Leader John Flanagan, Senate Majority Leader-elect Hon. Amy Paulin Andrea Stewart-Cousins, Assembly Minority Leader Brian Kolb, Sam Schwartz Mayor Bill de Blasio, NYC DOT Commissioner Polly