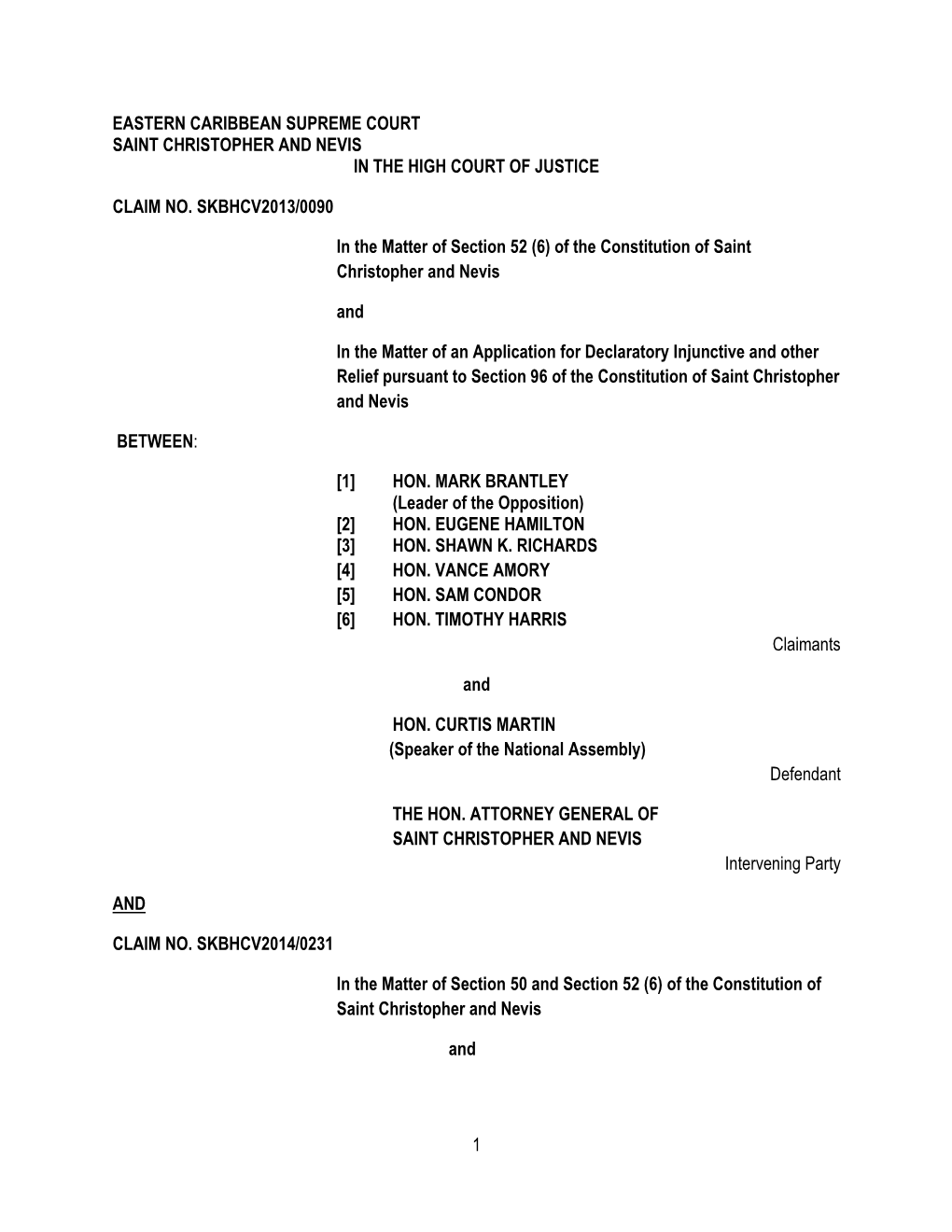

1 Eastern Caribbean Supreme Court Saint Christopher

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Statistical Digest

Past trends and Present position up to 2018 Basic Statistics NEVIS STATISTICAL DIGEST The Nevis Statistical Digest 2019 ©The Department of Statistics, Nevis All rights reserved. Published by the Department of Statistics Designed by Mentrice Warner-Arthurton The Department of Statistics TDC Building Island Main Road, Charlestown, Nevis Email: [email protected] Telephone: 1 (869) 469 5521 Ext 2168/2169 Fax: 1 (869) 469 0336 ____________ Disclaimer: While all care has been taken to produce accurate figures based on available data, the Department of Statistics does not accept any liability for any omission from such forecasts nor any loss or damage arising from the use of, or reliance on the information contained within this publication. The information presented in this publication does not reflect the opinion of the Department of Statistics. i Mission Statement To prepare meaningful, timely, accurate and reliable data, for purpose of decision making and macro-economic policy formulation; in an effort to stimulate economic development efforts by attracting new industry and investment to Nevis. That the statistics we publish are of the highest quality possible; That the general public will be confident that the information that they provide us with are secure; That the importance of the department will be recognized. “Another mistaken notion connected with the law of large numbers is the idea that an event is more or less likely to occur because it has or has not happened recently. The idea that the odds of an event with a fixed probability -

March 20, 2020

Page:1 The St.Kitts Nevis Observer - Friday March 20th, 2020 NEWS Page:2 The St.Kitts Nevis Observer - Friday March 20th, 2020 NEWS Grant fires back “My hands are clean.” By Loshaun Dixon Investment Programme. wanted. “It is a lot of He later filed a suitpolitics. on I have been Tourism Minister Dec 22, 2017 accus- very circumspect about Lindsay Grant has hit ing Grant and Powell of the matter. All I am tell- back against the naysay- breaching their fiduciary ing my constituents and ers spreading rumours duty and acted fraudu- the people of St. Kitts about him and his law lently in dealing with the and Nevis. I did not take partner Jonel Powell fol- purchase and sought a nobody’s money. I don’t lowing a recent judge- court order seeking the have anyone’s money.” ment that is forcing him return of the money after to appear before a legal he said the lawyers did Grant recalled that he tribunal, an action which not pay out the purchase was the only politician could ban him from price. in St. Kitts and Nevis to practicing law if found declare he and his fam- guilty of professional A fiery Grant in a gov- ily’s assets. “I am the misconduct. ernment townhall lashed only man in the history out against claims that of politics in this country “You have been hearing a lot on the radio and social media. I think politics is bigger than my personal matters. When people bang my name all over the place I have to come to the defense of my good name.” Grant and Powell have have been made over to put down my assets, been ordered to appear the airwaves regarding my wife’s assets and before a disciplinary tri- the matter. -

![Tuesday 23Rd September, 2014] [10:00 A.M.] List No](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/3183/tuesday-23rd-september-2014-10-00-a-m-list-no-1163183.webp)

Tuesday 23Rd September, 2014] [10:00 A.M.] List No

IN THE COURT OF APPEAL OF THE EASTERN CARIBBEAN SUPREME COURT CHAMBER HEARING [TUESDAY 23RD SEPTEMBER, 2014] [10:00 A.M.] LIST NO. 1- THOM, JA ANTIGUA AND BARBUDA [1] Robert Allen Stanford v [ANUHCVAP2014/0013] Stanford International Bank Limited (In Liquidation) et al Leave of appeal Video-conference before Blenman, JA @ 10 a.m. [2] John Faris v Lego Developments Ltd. [ANUHCVAP2014/0022] Stay of Execution [3] Vernon Quinland jr. v Karen Harris-Quinland [ANUHCVAP2014/0023] Notice of appeal be dismissed [4] Montpellier Farm Ltd. V Antigua Commercial Bank [ANUHCVAP2011/0007] Extension of time to file and serve skeleton arguments/relief from sanctions [5] Franciscus Petrus Vingerhoedt (Also Known as Frans Vingerhoedt) v Stanford International Bank Limited (In Liquidation) .. [ANUHCVAP2014/0030] Leave to appeal and stay of proceedings [6] Antigua Real Estates Limited v Rupert Kenlock [ANUHCVAP2010/0046] Attorney be removed from record COMMONWEALTH OF DOMINICA [7] Remy Lawrence trading as Rejens Services v Willem Nico aka Wilco Brouwer [DOMHCVAP2014/0014] Stay of Execution/Extension of time to comply with Court Order [8] Peter Lander v Fenty LaRocque [DOMHCVAP2014/0016] Leave to Appeal/Stay of proceedings [9] Steven Joseph v The State [DOMHCVAP2014/0003] Leave to Appeal [10] Paul Joseph v The Bank of Nova Scotia [DOMHCVAP2014/0017] Leave to appeal/Stay of proceedings [11] Glenworth O.N. Emanuel v Stephen K.M. Isidore [DOMHCVAP2014/0018] Leave to Appeal 1 [12] Levie Maximea v The Chief of Police et al [DOMHCVAP2013/0019] Extension of time to file submissions GRENADA [13] Hassan Hadeed v Nahla Hadeed [GDAHCVAP2014/0012] Leave to appeal [14] Damien Gangadeen v Sheldon Straker [GDAHCVAP2014/0016] Stay of Execution and Stay of Proceedings [15] Mable Phillips . -

ELECTORAL OBSERVATION MISSION FINAL REPORT General

ELECTORAL OBSERVATION MISSION FINAL REPORT GENERAL ELECTIONS THE FEDERATION OF SAINT KITTS AND NEVIS FEBRUARY 16, 2015 Secretariat for Political Affairs (SPA) Department of Electoral Cooperation and Observation (DECO) Electoral Observation Missions (EOMs) Organization of American States (OAS) ELECTORAL OBSERVATION MISSION FINAL REPORT ELECTORAL OBSERVATION MISSION FINAL REPORT General Elections in Saint Kitts and Nevis February 16, 2015 General Secretariat Organization of American States (SG/OAS) Luis Almagro1 Secretary General Nestor Méndez Assistant Secretary General Francisco Guerrero Secretary for Political Affaires Gerardo de Icaza Director Department for Electoral Cooperation and Observation 1 Secretary General, Luis Almagro and Assistant Secretary General, Nestor Méndez assumed office in May and July 2015, respectively. OAS Cataloging-in-Publication Data TABLE OF CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY . 7 CHAPTER I. INTRODUCTION 8 A. ELECTORAL OBSERVATION MISSIONS OF THE ORGANIZATION OF AMERICAN STATES (OAS/EOMS) 8 B. ORGANIZATION AND DEPLOYMEN OF THE MISSION 8 CHAPTER II. POLITICAL SYSTEM AND ELECTORAL ORGANIZATION 10 A. POLITICAL BACKGROUND 10 B. ELECTORAL LEGISLATION 12 C. ELECTORAL AUTHORITIES 15 CHAPTER III. MISSION ACTIVITIES AND OBSERVATIONS 17 A. PRE-ELECTORAL PERIOD 17 B. ELECTION DAY 25 C. POST-ELECTORAL PERIOD 26 CHAPTER IV. CONCLUSIONS 28 CHAPTER V. RECOMMENDATIONS 29 APPENDICES 32 ACRONYMS Organization of American States (OAS) Electoral Observation Missions (EOMs) OAS Electoral Observation Mission (OAS/EOM) Department for Electoral -

IN the Ldgh COURT of JUSTICE ST. CHRISTOPHER and NEVIS NEVIS CIRCUI)' A.D

IN THE lDGH COURT OF JUSTICE ST. CHRISTOPHER AND NEVIS NEVIS CIRCUI)' A.D. 2012 Claim No. NEVHCV201110130 In the Matter ofSection 3,12,15,18,20, (3),33,34,36,96,101(4) and 104 ofthe Constitution ofSaint Christopher and Nevis And In the matter ofthe National Assembly Elections Act Chap. 2:01 And In the Matter ofthe Nevis Island Assembly Electionfor the Constituency ofNevis 2 (parish ofSt. John) held on the 11th July, 2011. Between I Mark Brantley Petitioner And Hensley Daniel Leroy Benjamin (the Supervisor ofElections) Bernadette LaWrence (Registration Officer for the Constituency ofSt. John) Kelvin Daly (Returning Officer) Joseph Parry Premier ofNevis) Myrna Walwyn (Member, Electoral Commission) William The Attorney General ofSaint Christopher and Nevis for 1 Anthony Astaphan S. C. Sylvester Anthony for 2nd 3rd and4lh Respondents, I Arudranauth Gossai Oral Martin for 51h Respondent I Dennis Marchant for (lh, l' and ffh Respondents. John Tyne for Attorney General I JUDGMENT I On the 4th day of July, 2011 the Nevis Island Assembly elections were held. The Petitioner Mark Brantley, the Deputy Political Leader of the Concerned Citizens Movement (CCM) was a candidate for I the constituency of Nevis 2, Parish of St. John. The first Respondent, Hensley Daniel, a member of the Nevis Reformation Party (NRP) was also a candidate for the constituency ofNevis.2 Parish of S1. John. results of the elections were declared on the day by the fourth named respondent, the Returning Officer. Hensley Daniel, the first named Respondent, received 1,358 votes and the Petitioner received 1,344 votes. Hensley Daniel was, accordingly declared duly elected to the Nevis Island Assembly for the constituency of Nevis 2, Parish of St. -

Friday March 26Th, 2021 NEWS Page:1

Page:1 The St.Kitts Nevis Observer - Friday March 26th, 2021 NEWS Page:2 The St.Kitts Nevis Observer - Friday March 26th, 2021 LOCALNEWS NEWS St. Kitts welcomes ‘One Year Off’ film crew Several members of the Federal Cabi- net with cast of the movie ‘One Year Off’ By Loshaun Dixon reopening and eventually and Philippe Martinez hospitality and creative as a nation.” medium-term plans for beyond a pandemic, it for choosing St. Kitts industries.” the industry in St. Kitts With filming set to com- will do so with confidence and Nevis to make their He said the filming of this and Nevis. mence next month in St. as one of the few places in films, and making the He said the opportunities movie will inspire careers Kitts and Nevis on the the world recognized for Federation their “home created with the making in the film industry here “When I sat down with film “One Year Off”, offi- exemplary management away from home.” of these will help young in St. Kitts and Nevis. Mark Brantley and cials of MSR Media have of COVID-19. people reach their full Timothy Harris, the films claimed the opportunity “Today we thank you for potential. “It will inject interest and we brought with us in- could lead to future op- “We are confident that taking this story of a very curiosity in the global cluded 50 crew members, portunities for a broader what you will find in St. successfully managed “Mr Martinez, I recall community, putting St. and on top of that, we film industry in St. -

CCM 2010 Manifesto

Concerned Citizens Movement Manifesto 2010 ALL THREE FOR WE LEADERSHIP YOU CAN TRUST CONCERNED CITIZENS MOVEMENT Memorializing The Life and Times of The Hon Malcolm Guishard Although we have had a by-election to fill the vacancy in St. Paul’s/St. John’s Constituency – Nevis 9, following the untimely passing of the Hon. Earl Malcolm Guishard on 12th June 2007, and the Concerned Citizens Movement was successful in retaining the seat, these are the first general elections since the death of our beloved stalwart. Much has been said about the life and times of the Hon. Malcolm Guishard or “Guish” as he was affectionately known. Notwithstanding all that has been said, much more needs to be said. The Concerned Citizens Movement is eternally grateful for the contribution he has made. His political savvy, coupled with his wellspring of energy and verve were dispensed selflessly and our Party, our beloved island of Nevis and indeed the Federation of St. Kitts/Nevis have been the beneficiaries. The Hon. Malcolm Guishard served the Concerned Citizens Movement for twenty (20) years. He served the people of Nevis in government for fourteen (14) years. He represented the Constituency of St. John’s in the Nevis Island Assembly for fourteen years. He represented the Constituency of St. Paul’s/St. John’s in the Federal Assembly for fourteen (14) years and the people of St. Kitts and Nevis for four (4) years as Leader of the Opposition in the Federal Parliament. There is perhaps no other who has consistently, passionately and vociferously championed the need for Nevis to have its own independent government than the Hon. -

Saint Kitts and Nevis 2018 Human Rights Report

SAINT KITTS AND NEVIS 2018 HUMAN RIGHTS REPORT EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Saint Kitts and Nevis is a multiparty parliamentary democracy and federation. Queen Elizabeth II is the head of state. The governor general is the queen’s representative in the country and certifies all legislation on her behalf. The constitution provides the smaller island of Nevis considerable self-government under a premier. In the 2015 national elections, Team Unity, a coalition of three opposition parties, won seven of the 11 elected seats in the legislature. Team Unity leader Timothy Harris was elected prime minister. Independent observers from the Organization of the American States (OAS) concluded the election was generally free and fair but called for electoral reform, noting procedural difficulties in the election process resulted in the slow transmission of results. Civilian authorities maintained effective control over the security forces. Human rights issues included child abuse and criminalization of same-sex activity between men, although the law was not enforced during the year. The government took steps to prosecute and convict officials who committed abuses, but some cases remained unresolved. Section 1. Respect for the Integrity of the Person, Including Freedom from: a. Arbitrary Deprivation of Life and Other Unlawful or Politically Motivated Killings There were no reports that the government or its agents committed arbitrary or unlawful killings. b. Disappearance There were no reports of disappearances by or on behalf of government authorities. c. Torture and Other Cruel, Inhuman, or Degrading Treatment or Punishment SAINT KITTS AND NEVIS 2 The constitution prohibits such practices, and there were no reports that government officials employed them. -

CDR Draft Provisional Programme

Distr. LIMITED LC/L. (CDR.5/1) 24 April 2018 Rev.16 ORIGINAL: ENGLISH Fifth meeting of the Caribbean Development Roundtable Promoting climate resilience and sustainable economic growth in the Caribbean. Gros Islet, 26 April 2018 PROVISIONAL PROGRAMME 0815 hrs – 0855 hrs Registration 0855 hrs – 0900 hrs Security briefing 0900 hrs – 0920 hrs Opening of the meeting Statement by Raúl Garcia Buchaca, Deputy Executive Secretary for Management and Programme Analysis, Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean (ECLAC) Statement by The Honourable Allen Michael Chastanet, Prime Minister of Saint Lucia, Minister for Finance, Economic Growth, Job Creation, External Affairs and the Public Service 0920 hrs – 1030 hrs Implementing the ECLAC debt swap initiative Presentation by Daniel Titleman, Director, Economic Development Division, ECLAC Plenary discussion 1030 hrs – 1100 hrs Official group photo and coffee break 1100 hrs – 1230 hrs Financing green investment for resilience building and structural transformation in the Caribbean Moderator: The Honourable Oliver Joseph, Minister for Trade, Industry and Cooperatives and CARICOM Affairs, Grenada Patrick McCaskie, Director, Research and Planning Unit, Ministry of Finance and Economic Affairs, Barbados Nirad Tewarie, Chief Executive Officer, American Chamber of Commerce of Trinidad and Tobago Diann Black-Layne, Chief Environment Officer, Antigua and Barbuda - 2 - 1230 hrs – 1400 hrs Lunch 1400 hrs – 1530 hrs Promoting fiscal responsibility and financial management within the context of the -

![Joseph Parry V Mark Brantley; Leroy Benjamin (The Supervisor of Elections) and Another V Mark Brantley; Hensley Daniel V Mark Brantley - [2012] ECSCJ No](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/1358/joseph-parry-v-mark-brantley-leroy-benjamin-the-supervisor-of-elections-and-another-v-mark-brantley-hensley-daniel-v-mark-brantley-2012-ecscj-no-4101358.webp)

Joseph Parry V Mark Brantley; Leroy Benjamin (The Supervisor of Elections) and Another V Mark Brantley; Hensley Daniel V Mark Brantley - [2012] ECSCJ No

Page 1 Eastern Caribbean Supreme Court Reports/ 2012 / St. Kitts and Nevis / Joseph Parry v Mark Brantley; Leroy Benjamin (The Supervisor of Elections) and another v Mark Brantley; Hensley Daniel v Mark Brantley - [2012] ECSCJ No. 233 [2012] ECSCJ No. 233 Joseph Parry v Mark Brantley; Leroy Benjamin (The Supervisor of Elections) and another v Mark Brantley; Hensley Daniel v Mark Brantley HCVAP 2012/003 HCVAP 2012/004 HCVAP 2012/005 EASTERN CARIBBEAN SUPREME COURT; COURT OF APPEAL; FEDERATION OF SAINT CHRISTOPHER AND NEVIS; NEVIS CIRCUIT Pereira, J.A., Baptiste, J.A., Mitchell, J.A. [Ag.] 5 July 2012, 6 July 2012 27 August 2012 Dr. Henry Browne, Mr. Oral Martin with him, for Mr. Joseph Parry and Mr. Hensley Daniel Mr. Anthony Astaphan, SC, Mr. Sylvester Anthony with him, instructed by Ms. Angela Sookoo of Sylvester Anthony & Associates for Mr. Leroy Benjamin and Ms. Bernadette Lawrence Mr. Douglas Mendes, SC, Mr. Dane Hamilton QC, Mr. Keithley Lake, Ms. Jean Dyer, Ms. Dahlia Joseph, and Mr. Brian Barnes with him for Mr. Mark Brantley Page 2 Election petition appeal - Whether Constitution establishes a special Constitutional Court - Whether Elections Act establishes a special Elections Court of limited jurisdiction - 203 registered voters removed from the Register - List of objections not published by Returning Officer as required by Regulations - Notice of objection not given to objectees - Notice of hearing of objection sent by registered post - Objectees not receiving notices within the 5 days minimum time required by the Regulations -

1 “No Creditors' Winding up of International Business Companies

“No Creditors’ Winding Up of International Business Companies Formed in Nevis” Introduction The recent decision of the High Court in Nevis in the matter of Wang Ruiyun v. Gem Global Yield Fund Limited (Claim No. NEVHCV2011/0067) delivered by Mister Justice Redhead on 11 th November, 2011 emphatically states that there is no mechanism under Nevis law for a Creditor to wind up an international business company formed pursuant to the Nevis Business Corporation Ordinance 1984, as amended (“NBCO”). The Petition before the High Court in Nevis sought the winding up of a Nevis IBC by a judgment creditor which had obtained judgment against the IBC in the Hong Kong Courts. Efforts to conduct an oral examination of the directors of the company in Hong Kong proved futile as the directors were evading service. The Petitioner sued on the judgment debt in Nevis and obtained judgment in Nevis thereby converting the Hong Kong judgment to a Nevis judgment. Demands on the Company for payment proved futile. The debt was undisputed. The Judgment in Nevis had not been challenged and no payment had been made. The company had no known assets situate in Nevis. The issue then was solely one of enforcement and the Petitioner sought to wind up the Company and appoint liquidators on the basis that the Company was unable to pay its debts and or it was otherwise just and equitable for the Company to be wound up. Jurisdiction The jurisdiction of the Nevis High Court to order the winding up of a company incorporated under the provisions of the NBCO was the central question to be determined in the proceedings. -

![In the Court of Appeal of the Eastern Caribbean Supreme Court Saint Kitts and Nevis Preliminary Cause List [10Th to 14Th June, 2013]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/2718/in-the-court-of-appeal-of-the-eastern-caribbean-supreme-court-saint-kitts-and-nevis-preliminary-cause-list-10th-to-14th-june-2013-4552718.webp)

In the Court of Appeal of the Eastern Caribbean Supreme Court Saint Kitts and Nevis Preliminary Cause List [10Th to 14Th June, 2013]

IN THE COURT OF APPEAL OF THE EASTERN CARIBBEAN SUPREME COURT SAINT KITTS AND NEVIS PRELIMINARY CAUSE LIST [10TH TO 14TH JUNE, 2013] I. APPLICATIONS [1] Joseph Parry v Mark Brantley [Civ. App. No. 3, 4 & 5 of 2012] Bernadette Lawrence v Mark Brantley Hensley Daniel v Mark Brantley Review Costs Order [2] Kareem Vinton Ne’ Glasford v First Caribbean [Civ. Appeal No. 24 of 2012] International Bank (Barbados) Limited et al Leave to Appeal [3] West Indies Power (Nevis) Limited v Nevis Island [Civ. App. No. 3 of 2013] Administration Leave to Appeal II. HIGH COURT CRIMINAL APPEALS AGAINST SENTENCE [1] Talbert Warner v The Director of Public prosecutions [Crim. App. No. 20 of 2010] Embezzlement [1] The Director of Public Prosecutions v Kenrick Hendrickson [Civ. App. No. 2 of 2011] Indecent Assault III. HIGH COURT CRIMINAL APPEALS AGAINST CONVICTION [1] Louis Richards v The Director of Public Prosecutions [Crim. App. No. 30 of 2008] Murder [2] Kevin Jones v The Director of Public Prosecutions [Crim. App. No. 5 of 2010] Rape [3] Alexter Amory v The Director of Public Prosecutions [Crim. App. No. 13 of 2010] Armed Robbery Leon Phillip v The Director of Public Prosecutions [Crim. App. No. 15 of 2010] Armed Robbery Adjourned from last sitting IV. HIGH COURT CIVIL APPEALS [1] Hesketh Trevor Chapman v Nevis Cooperative Banking [Civ. App. No. 32 of 2003] Co. Ltd now called RBTT Bank (SKN) Limited [2] Leonora L. Walwyn v Eustace Archibald et al [Civ. App. No. 12 of 2010] [3] Steven G. Hites v Anguilla Business Services Ltd.