Behavioral and Physiological Effects of Deep Pressure on Children with Autism: a Pilot Study Evaluating the Efficacy of Grandin's Hug Machine

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Winter 2018 Incoming President Nancy Ponzetti-Dyer and Say a Heartfelt Goodbye to Laurie Raymond

Autism Society of Maine 72 B Main St, Winthrop, ME 04364 Fall Autism INSIDE Call:Holiday 1-800-273-5200 Sale Holiday Crafts Conference Items can be seenPage 8 Page 6 and ordered from ASM’s online store: Page 5 www.asmonline.org Silicone Chew Necklaces *Includes Gift Box Folding Puzzle Tote Animals & Shapes- $9.00 Add 5.5% Sales Tax $16.00 Raindrops & Circles-$8.00 Let ME Keychain Keychain Silver Ribbon Silver Puzzle Keychain $5.00 $5.00 $10.00 $10.00 $6.00spread the word on Maine Lanyard AUTISM Stretchy Wristband Ceramic Mug $6.00 $4.00 $3.00 $11.00 Lapel Pin $5.00 Magnets Small $3.00 Large $5.00 Glass Charm Bracelet Glass Pendant Earrings 1 Charm Ribbon Earrings $10.00 $15.00 $8.00 $6.00 $6.00 Maine Autism Owl Charm Colored Heart Silver Beads Colored Beads Autism Charm Charm $3.00 $1.00 $1.00 $3.00 $3.00 Developmental Connections Milestones by Nancy Ponzetti-Dyer The Autism Society of Maine would like to introduce our Winter 2018 incoming President Nancy Ponzetti-Dyer and say a heartfelt goodbye to Laurie Raymond. representatives have pledged to Isn’t it wonderful that we are never too old to grow? I was make this a priority. worried about taking on this new role but Laurie Raymond kindly helped me to gradually take on responsibilities, Opportunities for secretary to VP, each change in its time. Because this is my first helping with some of our President’s corner message, of course I went to the internet to priorities for 2019 help with this important milestone. -

Autism and New Media: Disability Between Technology and Society

1 Autism and new media: Disability between technology and society Amit Pinchevski (lead author) Department of Communication and Journalism, The Hebrew University of Jerusalem, Israel John Durham Peters Department of Communication Studies, University of Iowa, USA Abstract This paper explores the elective affinities between autism and new media. Autistic Spectrum Disorder (ASD) provides a uniquely apt case for considering the conceptual link between mental disability and media technology. Tracing the history of the disorder through its various media connections and connotations, we propose a narrative of the transition from impaired sociability in person to fluent social media by network. New media introduce new affordances for people with ASD: The Internet provides habitat free of the burdens of face-to-face encounters; high-tech industry fares well with the purported special abilities of those with Asperger’s syndrome; and digital technology offers a rich metaphorical depository for the condition as a whole. Running throughout is a gender bias that brings communication and technology into the fray of biology versus culture. Autism invites us to rethink our assumptions about communication in the digital age, accounting for both the pains and possibilities it entails. 2 Keywords: Autism (ASD), Asperger’s Syndrome, new media, disability studies, interaction and technology, computer-mediated communication, gender and technology Authors’ bios Amit Pinchevski is a senior lecturer in the Department of Communication and Journalism at the Hebrew University, Israel. He is the author of By Way of Interruption: Levinas and the Ethics of Communication (2005) and co-editor of Media Witnessing: Testimony in the Age of Mass Communication (with Paul Frosh, 2009) and Ethics of Media (with Nick Couldry and Mirca Madianou, 2013). -

For Individuals With

ASSISTIVE TECHNOLOGY FOR INDIVIDU A LS WITH COGNITIVE IMP A IRMENTS A Handbook for Idahoans with Cognitive Impairments and the People Who Care for Them Promoting greater access to technology for ASSISTIVE TECHNOLOGYIdahoans FOR INDIVIDU withA LS WITHcognitive COGNITIVE IimpairmentsMP A IRMENTS 1 Acknowledgements A number of people need to be thanked for their assistance in making this handbook a reality. First, a big thank you goes to the staff of the Idaho Assistive Technology Project for their help in conceptualizing, editing, and proof-reading the handbook. A special thank you to the North Dakota Interagency Program for Assistive Technology (IPAT), and especially to Judy Lee, for allowing the use of their materials related to assistive technology and people with cogni- tive disabilities. A special thank you also goes to Edmund Frank LoPresti, Alex Mihailidis, and Ned Kirsch for allowing the use of their materials connected to assistive technology and cognitive rehabilitation. Illustrations by Sarah Moore, Martha Perske, and Sue House Design by Jane Fredrickson Statement of Purpose This handbook is designed as a guide for individuals, families, and professionals in Idaho who are involved with persons who experience cognitive disabilities. The application of assistive technology for meeting the needs of individuals with cognitive disabilities is still in its infancy in Idaho. This handbook was developed to increase knowledge and expertise about the use of assistive technology for this population. The handbook also provides information about how to locate funding for needed devices and lists a broad array of resources related to this topic. The handbook is designed to provide information that can be used by persons of all ages. -

Temple Grandin Professeure De Zootechnie Et De Sciences Animales

TEMPLE GRANDIN PROFESSEURE DE ZOOTECHNIE ET DE SCIENCES ANIMALES Mary Temple Grandin, dite Temple Grandin, née le 29 août 1947 à Boston, est une femme autiste, professeure de zootechnie et de sciences animales à l'université d'État du Colorado, docteure et spécialiste de renommée internationale dans cette même discipline. Elle monte en 1980 une entreprise d’ingénierie et de conseils sur les conditions d'élevage des animaux de rente, qui fait d’elle une experte en conception d'équipements pour le bétail. En 2012, près de la moitié des abattoirs à bovins d'Amérique du Nord sont équipés du matériel qu'elle a conçu ; depuis les années 1980 jusqu'en 2016, elle a collaboré à environ 200 articles de recherche. Temple Grandin a été diagnostiquée avec des « dommages cérébraux » à l'âge de deux ans, et n'a pas parlé avant l'âge de trois ans et demi. Une intervention précoce lui a permis de progresser, de suivre sa scolarité jusqu'en doctorat, puis de vivre de son métier. Elle est également connue pour être la première personne autiste à avoir témoigné de son expérience de vie dans des autobiographies, Ma vie d'autiste en 1986 et Penser en images en 1995. Elle fait régulièrement appel à des techniques de scanographie, qui ont révélé le fonctionnement et la structure particulière de son cerveau spécialisé dans la pensée visuelle, une recherche publiée dans l'ouvrage Dans le cerveau des autistes, en 2013. Elle s’implique pour la défense du bien-être animal, plaidant pour une meilleure prise en compte de la souffrance animale pendant l'élevage et l'abattage, s’opposant en particulier à l'élevage en batterie. -

Effectiveness of Touch Therapy in Decreasing Self-Stimulatory and Off-Task Behavior in Children with Autism" (2005)

Ithaca College Digital Commons @ IC Ithaca College Theses 2005 Effectiveness of touch therapy in decreasing self- stimulatory and off-task behavior in children with autism Neva Fisher Ithaca College Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.ithaca.edu/ic_theses Part of the Occupational Therapy Commons Recommended Citation Fisher, Neva, "Effectiveness of touch therapy in decreasing self-stimulatory and off-task behavior in children with autism" (2005). Ithaca College Theses. Paper 88. This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by Digital Commons @ IC. It has been accepted for inclusion in Ithaca College Theses by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ IC. i {1", il.r,,'-'.,i/ ii'n" ;rr Eftctiveness ofTouch Therapy in Decreasing Self-stimulatory Behavior and oGtask Behavior in Children with Autism A Masters Thesis presentd to the Facutty ofthe Graduate Program in Occupational Therapy Ithaca College In partial fulfillment'ofthe rt4-irirements for the degree Masters of.Scidnce by Neva Fisher December 2005 Ithaca College School of Hehlth Sciences and Human Performance lthaca, New York CERTIFICATE OF APPROVAL This is to certify that the Thesis of \ Neva Fisher i. Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science in the'Department of Occupational Therapy, School of Health Sciences and Human Performance at Ithaca College has been approved. Committee Members: Candidate: Chair,Graduate Program in Occupational Thcrapy: Dean of Gradr"rate Studies: 一 ダ ‘ r 、 Abstract Objective: This single-zubject ABA studj'evalirirrdd the effectiveness ofproviding proprioceptive rnput tlroughtouch therapy to reduce the incidence of self-stimrrlatory and off-task behavior in a seven year-old cbild ri,ith autisnr Metbod: The baseline phase consisted of four days ofobservation ofthe child in his classroom for fifteen minutes. -

Effectiveness of Weighted Blankets As an Intervention for Sleep Problems in Children with Autism”

EFFECTIVENESS OF WEIGHTED BLANKETS AS AN INTERVENTION FOR SLEEP PROBLEMS IN CHILDREN WITH AUTISM Thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of a Master of Science in Child and Family Psychology at the University of Canterbury by Jane Charleson University of Canterbury 2014 2 Contents List of Tables ................................................................................................................. 6 List of Figures ................................................................................................................ 7 Acknowledgements ........................................................................................................ 8 Abstract .......................................................................................................................... 9 Chapter 1 Introduction ................................................................................................. 10 Definition of autism spectrum disorder ................................................................... 11 Development of sleep in children ............................................................................ 12 Assessment of sleep ................................................................................................. 14 Definition of sleep problems .................................................................................... 16 Prevalence and nature of sleep problems in children with autism ........................... 18 Development and maintenance of sleep problems in children with autism ............ -

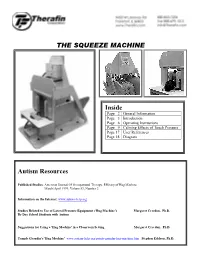

Squeeze Machine Indepth Information

THE SQUEEZE MACHINE Inside Page 2 General Information Page 3 Introduction Page 6 Operating Instructions Page 9 Calming Effects of Touch Pressure Page 17 User References Page 18 Diagram Autism Resources Published Studies: American Journal Of Occupational Therapy, Efficacy of Hug Machine March/April 1999, Volume53, Number 2 Information on the Internet: www.autism-help.org Studies Related to Use of Lateral Pressure Equipment ('Hug Machine') Margaret Creedon, Ph.D. By Day School Students with Autism Suggestions for Using a 'Hug Machine' in a Classroom Setting Margaret Creedon, Ph.D. Temple Grandin's 'Hug Machine' www.autism-help.org/points-grandin-hug-machine.htm Stephen Edelson, Ph.D. Squeeze Machine Page 2 Questions and Answers Q How Big Is It? Crated for shipment, the machine is 65" tall, 65" long and 54" wide. Uncrated, it is 60" tall, 60" long, and 32" wide. Crated, the complete system with compressor weighs almost 350 pounds. Q Who Can Use It? The Squeeze Machine can be used by most people because it is adjustable in a number of ways. The machine has a series of slots and holes to allow approximately fourteen inches of adjustment in width at the base of the pads. There are also slots to adjust the headrest height... slides to adjust for differing head widths... and the hand control center is adjustable from side to side and from front to back. One set of pads is included, which will accommodate either children or adults. Q What Is It Made Of? The basic structure is constructed from thirteen-ply 3/4" birch plywood. -

February Spark 3

How to Build a Hug Written by Amy Guglielmo / Illustrated by Giselle Potter 96 pages / Grades 2 - 5 All grade levels will take something away from this real story about Temple Grandin, a celebrated scientist and autism advocate who inspires others to acknowledge and embrace what makes each person different and unique. C A T C H Context Arts Themes Create Heart Words Temple Grandin is Giselle Potter is a Embracing your Think about Author’s Note: “I use known around the celebrated children’s unique self. something you do not my mind to solve world for her work author, having like that everyone problems and invent and advocacy for illustrated numerous Finding ways to solve else you know does things - Temple awareness of autism. books. Her style is problems that work like. Try to recognize Grandin” Being a person with uniquely her own - a for you / alternate WHY you don’t like it. autism herself, bit of folk art, a bit solutions. Can you create/ Last page: “I’m into Temple has learned childlike and design/build hugging people how to use her own whimsical, yet always Accepting and something to let you now.” experiences to captivating. What is it tolerating other’s experience it in a way celebrate and about this artist, different learning and that would work for pgs 30-31: “It’s a acknowledge the whose work is a bit living styles. you? Celebrate this snuggle apparatus… ways in which she is different, that aligns part of you - don’t It’s a hug machine.” different from so nicely with the Creative thinking hide it! others, a skill we story of Temple could all learn from. -

Presenting Counter-Metaphors in the Study of the Discourse of Autism and Negotiations of Space in Literature and Visual Culture

In constant encounter with one’s environment: Presenting counter-metaphors in the study of the discourse of autism and negotiations of space in literature and visual culture MA thesis Hannah Ebben Radboud University Nijmegen Research Masters Historical, Literary and Cultural Studies: Art and Visual Culture Thesis supervisor: dr. László Munteán Second reader: dr. Mitzi Waltz Number of words: 29767 1 Table of contents Introduction 4 Autism as a discourse 4 Autism and spatial metaphors 6 No ‘autism’ without spaces 7 From ‘autos’ to ‘atopos’ 9 Thesis structure 12 Case Studies 13 What is the discourse of autism in Rain Man and Extremely Loud and Incredibly Close? 15 My approach of the discourse of autism in speech and culture 16 Deviating from existing literature on cultural representations of autism 20 The use of autism-related words in Rain Man and Extremely Loud and Incredibly Close 22 Indexes of deviance in Rain Man and Extremely Loud 25 Conclusions 30 How do YouTube videos made by people who identify with the label of autism represent and negotiate subjectivity in space? 32 Deviations from autos in YouTube-video’s 33 Atopos and YouTube videos 37 What is a counter-metaphor? 42 Conclusions 44 How can the atopos counter-metaphor be integrated as a theoretical concept in the study of space in film and literature? 45 Atopos and the ‘misfit’; strengths and restrictions 47 How are negotiations through urban space in London represented in the literary works on autism Born on a Blue Day and The Curious Incident of the Dog in the Night-Time? 51 How are affinities with animals within negotiations of space depicted in mediated personal accounts of Dawn Prince-Hughes and Temple Grandin? 55 Conclusions 61 2 Conclusions 63 References 66 Appendix: Figures 72 3 Introduction My Research Master thesis inquires the discourse of autism and negotiations of space in literature and visual culture. -

9781534410978 Cg How to Build a Hug.Pdf

A Curriculum Guide to Temple Grandin and Her Amazing Squeeze Machine How to Build a Hug by Amy Guglielmo and Jacqueline Tourville Illustrated by Giselle Potter HC: 9781534410978 • EB: 9781534410985 Ages 4–8; Grades P–3 • Atheneum BACKGROUND/SUMMARY As a young girl, Temple Grandin liked to design and make things. What she didn’t like were scratchy socks, high- pitched sounds, bright lights, and smelly perfumes. She was very sensitive to sounds, smells, and touch. Being hugged was so upsetting, she even avoided being hugged by her mother. Yet she did want to feel a real hug. She wondered what hugs were supposed to feel like. The solution to Temple’s problem came when she spent the summer at her aunt’s ranch in Arizona. There she saw a mysterious device called a squeeze chute that calmed a young cow by giving it a comforting squeeze. This sight sparked Temple’s idea to design and make her own hugging machine, which she used to comfort herself when she was nervous. By the time the machine finally broke, she found she no longer needed it. “I’m into hugging people now,” she declared. This book introduces readers to the early life of Temple Grandin, a well-known spokesperson for autism spectrum disorders (ASD). By using her abilities to think visually, draw, paint, design, and build things, Temple has pursued a career as an industry consultant, professor of animal science at Colorado State University, and author of ten books and hundreds of articles. As the authors of this book tell us, “Temple’s story is as unique as she is, and the legacy of her hug machine lives on.” It is one of her many accomplishments. -

Childhood Autism and Benefits of Different Therapy Types

CHILDHOOD AUTISM AND BENEFITS OF DIFFERENT THERAPY TYPES by Amy L. Hanson A SENIOR THESIS m GENERAL STUDIES Submitted to the General Studies Council in the College of Arts and Sciences at Texas Tech University in Partial fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of BACHELOR OF GENERAL STUDIES Approved 'JSROf:ESSOR JOYCE ARTERBURN Department of Exercise and Sports Sciences Chairperson of Thesis Corum ittee PROfESSOR LAURA BORCHARDT Department of Exercise and Sports Sciences PROFESSOR VINCE LEMBO Department of Psychology Tarrant County College Accepted PROFESSoR MitHAEL SCHOENECKE Director of General Studies AUGUST 2001 -"fl ~oot ACKNO~EDGEMENTS tlO·IJ C , ;;._.. I would like to thank my thesis committee, Professors Joyce Arterburn, Laura Borschardt, and Vincent Lambo, and Director of General Studies. Michael Schoenecke. for all their support, enthusiasm, and kindness. Without their understanding and belief in me, I could not have completed my thesis. In addition to my committee and director. I also want to acknowledge my family and friends who continually supported me with their understanding and fellowship during the period in which this thesis was written . .. 11 TABLE OF CONTENTS .. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ·························································································· 11 CHAPTER I. INTRODUCTION TO AUTISM I Disordered Language . .. 3 Social Impairment . .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. 4 Social Awkwardness . .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. . -

The Six Hug Commandments: Design and Evaluation of a Human-Sized Hugging Robot with Visual and Haptic Perception

The Six Hug Commandments: Design and Evaluation of a Human-Sized Hugging Robot with Visual and Haptic Perception Alexis E. Block Sammy Christen Roger Gassert MPI-IS and ETH Zürich ETH Zürich ETH Zürich Stuttgart, Germany Zürich, Switzerland Zürich, Switzerland Otmar Hilliges Katherine J. Kuchenbecker ETH Zürich MPI for Intelligent Systems Zürich, Switzerland Stuttgart, Germany ABSTRACT Receiving a hug is one of the best ways to feel socially supported, and the lack of social touch can have severe negative effects on an individual’s well-being. Based on previous research both within and outside of HRI, we propose six tenets (“commandments”) of natural and enjoyable robotic hugging: a hugging robot should be soft, be warm, be human sized, visually perceive its user, adjust its embrace to the user’s size and position, and reliably release when the user wants to end the hug. Prior work validated the first two tenets, and the final four are new. We followed all six tenets to create anew robotic platform, HuggieBot 2.0, that has a soft, warm, inflated body (HuggieChest) and uses visual and haptic sensing to deliver closed- loop hugging. We first verified the outward appeal of this platform in comparison to the previous PR2-based HuggieBot 1.0 via an on- line video-watching study involving 117 users. We then conducted an in-person experiment in which 32 users each exchanged eight hugs with HuggieBot 2.0, experiencing all combinations of visual hug initiation, haptic sizing, and haptic releasing. The results show Figure 1: A user hugging HuggieBot 2.0. that adding haptic reactivity definitively improves user perception a hugging robot, largely verifying our four new tenets and illumi- and anxiety, and increase the body’s levels of oxytocin, but it also nating several interesting opportunities for further improvement.