Effectiveness of Weighted Blankets As an Intervention for Sleep Problems in Children with Autism”

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

ENO Directory Over 20 Years Ago We Pioneered the Hammock Counter-Culture

ENO Directory Over 20 years ago we pioneered the hammock counter-culture. Environmental Conservation As a hammock company, we know the importance of trees and so do our customers. Since then, we’ve ventured We believe that when given the chance, individuals will use their purchasing power from mountains to sea, to protect the planet, which is why we plant two trees in an area of need for every hammock sold. Additionally, we proudly pledge 1% of our annual sales to support from backyard to backcountry, nonprofit organisations focused on environmental solutions. and everywhere in between. — MEMBER — No matter your passion or pursuit, our tried-and-true products outfit Materials & Chemistry you with an all-access pass to We are committed to the journey of building more sustainable and responsibly made explore, connect and relax... products. This includes sourcing high-quality materials with post-consumer recycled content and bluesign® approved chemistry, as well as adopting safer ingredients for water repellents, colour dyes, and beyond. We have adopted the industry leading bluesign® Restricted Substances List (RSL) which provides a comprehensive system for managing chemical hazards, workplace safety, and environmental impacts during material production. To support our RSL, we have set up a testing program with an accredited third-party laboratory and have placed an emphasis on priority chemicals of concern established by the outdoor industry. We look forward to sharing our progress along the way. Hammocks 3 - 6 Social Responsibility We protect the welfare of our community and the planet from the beginning to the end Specialist Hammocks 7 - 9 of our product life cycle through a strict code of conduct, product repair and take- back programs. -

Winter 2018 Incoming President Nancy Ponzetti-Dyer and Say a Heartfelt Goodbye to Laurie Raymond

Autism Society of Maine 72 B Main St, Winthrop, ME 04364 Fall Autism INSIDE Call:Holiday 1-800-273-5200 Sale Holiday Crafts Conference Items can be seenPage 8 Page 6 and ordered from ASM’s online store: Page 5 www.asmonline.org Silicone Chew Necklaces *Includes Gift Box Folding Puzzle Tote Animals & Shapes- $9.00 Add 5.5% Sales Tax $16.00 Raindrops & Circles-$8.00 Let ME Keychain Keychain Silver Ribbon Silver Puzzle Keychain $5.00 $5.00 $10.00 $10.00 $6.00spread the word on Maine Lanyard AUTISM Stretchy Wristband Ceramic Mug $6.00 $4.00 $3.00 $11.00 Lapel Pin $5.00 Magnets Small $3.00 Large $5.00 Glass Charm Bracelet Glass Pendant Earrings 1 Charm Ribbon Earrings $10.00 $15.00 $8.00 $6.00 $6.00 Maine Autism Owl Charm Colored Heart Silver Beads Colored Beads Autism Charm Charm $3.00 $1.00 $1.00 $3.00 $3.00 Developmental Connections Milestones by Nancy Ponzetti-Dyer The Autism Society of Maine would like to introduce our Winter 2018 incoming President Nancy Ponzetti-Dyer and say a heartfelt goodbye to Laurie Raymond. representatives have pledged to Isn’t it wonderful that we are never too old to grow? I was make this a priority. worried about taking on this new role but Laurie Raymond kindly helped me to gradually take on responsibilities, Opportunities for secretary to VP, each change in its time. Because this is my first helping with some of our President’s corner message, of course I went to the internet to priorities for 2019 help with this important milestone. -

Autism and New Media: Disability Between Technology and Society

1 Autism and new media: Disability between technology and society Amit Pinchevski (lead author) Department of Communication and Journalism, The Hebrew University of Jerusalem, Israel John Durham Peters Department of Communication Studies, University of Iowa, USA Abstract This paper explores the elective affinities between autism and new media. Autistic Spectrum Disorder (ASD) provides a uniquely apt case for considering the conceptual link between mental disability and media technology. Tracing the history of the disorder through its various media connections and connotations, we propose a narrative of the transition from impaired sociability in person to fluent social media by network. New media introduce new affordances for people with ASD: The Internet provides habitat free of the burdens of face-to-face encounters; high-tech industry fares well with the purported special abilities of those with Asperger’s syndrome; and digital technology offers a rich metaphorical depository for the condition as a whole. Running throughout is a gender bias that brings communication and technology into the fray of biology versus culture. Autism invites us to rethink our assumptions about communication in the digital age, accounting for both the pains and possibilities it entails. 2 Keywords: Autism (ASD), Asperger’s Syndrome, new media, disability studies, interaction and technology, computer-mediated communication, gender and technology Authors’ bios Amit Pinchevski is a senior lecturer in the Department of Communication and Journalism at the Hebrew University, Israel. He is the author of By Way of Interruption: Levinas and the Ethics of Communication (2005) and co-editor of Media Witnessing: Testimony in the Age of Mass Communication (with Paul Frosh, 2009) and Ethics of Media (with Nick Couldry and Mirca Madianou, 2013). -

Excessive Daytime Sleepiness in Children and Adolescents Across the Weight Spectrum

Excessive Daytime Sleepiness in Children and Adolescents across the Weight Spectrum by Lilach Kamer A thesis submitted in conformity with the requirements for the degree of Master of Science Institute of Medical Science University of Toronto © Copyright by Lilach Kamer 2011 Excessive Daytime Sleepiness in Children and Adolescents across the Weight Spectrum. Lilach Kamer Master of Science Institute of Medical Science University of Toronto 2011 Abstract A relationship between overweight and excessive daytime sleepiness (EDS) has been suggested in the adult population, and to a limited extent in the pediatric population. Daytime sleepiness can interfere with various components of daytime function. In light of the increase in the rates of pediatric overweight and obesity, the aim of this study was to investigate the relationship between weight and EDS in a pediatric population. Using a retrospective approach, data collected in a pediatric sleep clinic was analyzed. Objective measures of EDS were correlated with age, gender, body mass index percentile, and overnight sleep test recording variables. In males and in all children under the age of 13 years old, EDS was more common in those weighing above the normal range, EDS was present particularly during mid-morning hours. Additionally, weight above the normal range correlated with evidence of EDS after adjusting for measures of sleep pathologies. - ii - Acknowledgments First and foremost, I would like to thank my supervisor, Dr. Colin Shapiro for the opportunity to work and learn at the Youthdale Child and Adolescent Sleep Center, and for patiently developing my budding research skills. To the staff at the Youthdale Child and Adolescent Sleep Center, especially Dragana Jovanovic and Inna Voloh, for introducing me into the intricate world of pediatric sleep testing as well as Dora Zalai and Rose Lata for their patience, advice, dedication and willingness to accommodate my research needs…and for smiling while they do this. -

Abstract Use of a Pressure Vest to Reduce the Physiological Arousal

Abstract Use of a Pressure Vest to Reduce the Physiological Arousal of People with Profound Intellectual and Physical Disabilities During Routine Nail Care by Rebecca LaChappelle March, 2009 Director: Dr. Beth Velde PhD, OTR/L DEPARTMENT OF OCCUPATIONAL THERAPY This single subject ABAB study explored whether the use of a commercially available deep pressure vest would decrease physiological arousal in a male with profound mental retardation during nail care activities. Psychophysiological responses of electrodermal activity, skin temperature, electromyography, and heart rate were used as indicators of physiological arousal and recorded using the NeXus-10. Visual and statistical analysis revealed that the use of the deep pressure vest did not reduce physiological arousal during nail care. ©Copyright 2009 Rebecca LaChappelle Use of a Pressure Vest to Reduce the Physiological Arousal of People with Profound Intellectual and Physical Disabilities During Routine Nail Care A thesis Presented To The Faculty of the Department of Occupational Therapy East Carolina University In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Masters of Science of Occupational Therapy by Rebecca LaChappelle March, 2009 Use of a Pressure Vest to Reduce the Physiological Arousal of People with Profound Intellectual and Physical Disabilities During a Routine Grooming Activity by Rebecca LaChappelle APPROVED BY: DIRECTOR OF THESIS:__________________________________________________ Beth Velde, PhD, OTR/L COMMITTEE MEMBER:__________________________________________________ Carol Lust, EdD, OTR/L COMMITTEE MEMBER:__________________________________________________ David Loy, PhD, LRT/CTRS COMMITTEE MEMBER:__________________________________________________ Suzanne Hudson, PhD CHAIR OF THE DEPARTMENT OF OCCUPATIONAL THERAPY: ________________________________________________ Leonard Trujillo, PhD, OTR/L INTERIM DEAN OF THE GRADUATE SCHOOL: ________________________________________________ Paul Gemperline, PhD 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS LIST OF TABLES……………………………………………………………….. -

Contemporary DIY Four Poster Bed

Contemporary DIY Four Poster Bed Here are a few housekeeping items before you start that will make this project even easier to tackle. First, this bed needs to be assembled in the space in the bedroom it will be in. The assembled parts are larger than a doorway. I stained and waxed my wood pieces before assembling. Since the wood was already finished, I placed a heavy moving blanket on the floor to protect the wood from scratches. Time to complete: 2-3 days Lumber: 2 - 1” x 2” x 8ft poplar 16 - 1” x 3” x 6ft poplar 2 – 2” x 2” x 6ft poplar 6 - 1” x 6” x 6ft maple 3 – 2” x 2” x8ft maple 2 – 2” x 3” x 8ft maple 2 – 2” x 6” x 6ft maple 4 – 3” x 3” x 8ft maple Materials: Pocket screws 1 ¼ Pocket screws 2 ” Wood screws 1 ¼ ” Wood screws 1 ½ “ Wood glue Sand paper Stain or paint to finish Cut List: Maple 4 - 3” x 3” at 78 ¾” bed posts 2 - 2” x 2” at 60 ½“ top rails 2 - 2” x 6” at 60 ½” footboard and lower headboard planks 6 – 1” x 6” at 60 ½” headboard planks 2 – 2” x 2” at 80 ½” upper rails 2 – 2” x 4” at 80 ½” lower side rails Poplar 2 – 1’ x 2’ at 80 ½” slat cleat 1 – 2’ x 2’ at 80 ½” center support 1 – 2” x 2” at 9 ¼” center support legs 16 – 1” x 3” at 60 ½” slats Preparation Cut, sand and finish all of the maple pieces. -

For Individuals With

ASSISTIVE TECHNOLOGY FOR INDIVIDU A LS WITH COGNITIVE IMP A IRMENTS A Handbook for Idahoans with Cognitive Impairments and the People Who Care for Them Promoting greater access to technology for ASSISTIVE TECHNOLOGYIdahoans FOR INDIVIDU withA LS WITHcognitive COGNITIVE IimpairmentsMP A IRMENTS 1 Acknowledgements A number of people need to be thanked for their assistance in making this handbook a reality. First, a big thank you goes to the staff of the Idaho Assistive Technology Project for their help in conceptualizing, editing, and proof-reading the handbook. A special thank you to the North Dakota Interagency Program for Assistive Technology (IPAT), and especially to Judy Lee, for allowing the use of their materials related to assistive technology and people with cogni- tive disabilities. A special thank you also goes to Edmund Frank LoPresti, Alex Mihailidis, and Ned Kirsch for allowing the use of their materials connected to assistive technology and cognitive rehabilitation. Illustrations by Sarah Moore, Martha Perske, and Sue House Design by Jane Fredrickson Statement of Purpose This handbook is designed as a guide for individuals, families, and professionals in Idaho who are involved with persons who experience cognitive disabilities. The application of assistive technology for meeting the needs of individuals with cognitive disabilities is still in its infancy in Idaho. This handbook was developed to increase knowledge and expertise about the use of assistive technology for this population. The handbook also provides information about how to locate funding for needed devices and lists a broad array of resources related to this topic. The handbook is designed to provide information that can be used by persons of all ages. -

Temple Grandin Professeure De Zootechnie Et De Sciences Animales

TEMPLE GRANDIN PROFESSEURE DE ZOOTECHNIE ET DE SCIENCES ANIMALES Mary Temple Grandin, dite Temple Grandin, née le 29 août 1947 à Boston, est une femme autiste, professeure de zootechnie et de sciences animales à l'université d'État du Colorado, docteure et spécialiste de renommée internationale dans cette même discipline. Elle monte en 1980 une entreprise d’ingénierie et de conseils sur les conditions d'élevage des animaux de rente, qui fait d’elle une experte en conception d'équipements pour le bétail. En 2012, près de la moitié des abattoirs à bovins d'Amérique du Nord sont équipés du matériel qu'elle a conçu ; depuis les années 1980 jusqu'en 2016, elle a collaboré à environ 200 articles de recherche. Temple Grandin a été diagnostiquée avec des « dommages cérébraux » à l'âge de deux ans, et n'a pas parlé avant l'âge de trois ans et demi. Une intervention précoce lui a permis de progresser, de suivre sa scolarité jusqu'en doctorat, puis de vivre de son métier. Elle est également connue pour être la première personne autiste à avoir témoigné de son expérience de vie dans des autobiographies, Ma vie d'autiste en 1986 et Penser en images en 1995. Elle fait régulièrement appel à des techniques de scanographie, qui ont révélé le fonctionnement et la structure particulière de son cerveau spécialisé dans la pensée visuelle, une recherche publiée dans l'ouvrage Dans le cerveau des autistes, en 2013. Elle s’implique pour la défense du bien-être animal, plaidant pour une meilleure prise en compte de la souffrance animale pendant l'élevage et l'abattage, s’opposant en particulier à l'élevage en batterie. -

Sleeping While Awake Lant

CONSCIOUSNESS REDUX “It was literally true: I was going through life asleep. My body had no more feeling than a drowned corpse. My very existence, my life in the world, seemed like a hallucination. A strong wind would make me think my body was about to be blown to the end of the earth, to some land I had never seen or heard of, where my mind and body would separate forever.” —From Sleep, by Haruki Murakami, 1989 PHYSIOLOGY turn off—your mind remains hypervigi- Sleeping While Awake lant. You toss and turn but can’t find the blessed relief of sleep. The reasons for During microsleep, the entire brain nods off so briefly that we often don’t notice it. sleeplessness may be many, but the con- ) Now research shows that individual neurons in the brain can slumber, too, sequences are always the same: You are Koch fatigued the following day, you feel especially when we are sleep-deprived E ( sleepy, you nap. Attention wanders, your B CA We’ve all been there. You go to bed, reaction time slows, you have less cogni- C close your eyes, blanket your mind and tive-emotional control. Fortunately, BY CHRISTOF KOCH wait for consciousness to fade. A timeless fatigue is reversible and disappears after ); SEAN M Christof Koch is president interval later, you wake up, refreshed a night or two of solid sleep. and chief scientific officer at and ready to face the challenges of a new We spend about one third of our lives the Allen Institute for Brain day (note how you can never catch your- in a state of repose, defined by relative illustration Science in Seattle. -

Effectiveness of Touch Therapy in Decreasing Self-Stimulatory and Off-Task Behavior in Children with Autism" (2005)

Ithaca College Digital Commons @ IC Ithaca College Theses 2005 Effectiveness of touch therapy in decreasing self- stimulatory and off-task behavior in children with autism Neva Fisher Ithaca College Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.ithaca.edu/ic_theses Part of the Occupational Therapy Commons Recommended Citation Fisher, Neva, "Effectiveness of touch therapy in decreasing self-stimulatory and off-task behavior in children with autism" (2005). Ithaca College Theses. Paper 88. This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by Digital Commons @ IC. It has been accepted for inclusion in Ithaca College Theses by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ IC. i {1", il.r,,'-'.,i/ ii'n" ;rr Eftctiveness ofTouch Therapy in Decreasing Self-stimulatory Behavior and oGtask Behavior in Children with Autism A Masters Thesis presentd to the Facutty ofthe Graduate Program in Occupational Therapy Ithaca College In partial fulfillment'ofthe rt4-irirements for the degree Masters of.Scidnce by Neva Fisher December 2005 Ithaca College School of Hehlth Sciences and Human Performance lthaca, New York CERTIFICATE OF APPROVAL This is to certify that the Thesis of \ Neva Fisher i. Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science in the'Department of Occupational Therapy, School of Health Sciences and Human Performance at Ithaca College has been approved. Committee Members: Candidate: Chair,Graduate Program in Occupational Thcrapy: Dean of Gradr"rate Studies: 一 ダ ‘ r 、 Abstract Objective: This single-zubject ABA studj'evalirirrdd the effectiveness ofproviding proprioceptive rnput tlroughtouch therapy to reduce the incidence of self-stimrrlatory and off-task behavior in a seven year-old cbild ri,ith autisnr Metbod: The baseline phase consisted of four days ofobservation ofthe child in his classroom for fifteen minutes. -

Safe Sleep: Information for Parents

Safe Sleep: Information for Parents SIDS Crib The term SIDS, or sudden infant death syndrome, A crib can be a crib, bassinet, Pack-N-Play, is used to describe when babies die in their sleep play-yard, or playpen, but it should have a firm without any warning before their first birthday. In mattress and be covered with a well-fitted sheet the early 1990s, parents were told to stop putting only. It is very dangerous for babies to sleep on babies on their tummies to sleep. They were told to a sofa or armchair, because they can wiggle as put them on their backs or sides only. Later, they sleep and get trapped and be smothered. It experts said the side position wasn’t safe either, so is also not safe for them to sleep in a car seat, parents were told to put their babies only on their bouncy seat, swing, baby carrier, or sling, backs. because their neck can bend in ways that makes it hard for them to breathe. Today, we know that just putting babies on their backs to sleep is not enough to keep some of them There are some other very important things that from dying in their sleep. There are many other can help babies sleep safely: easy things parents can do to keep their babies safe Smoking—Keep babies away from people when they sleep. who smoke. We know that babies who are around people who smoke or babies born to Safe Sleep mothers who smoke have a higher risk of “ABC” is an easy way to remember how to make SIDS. -

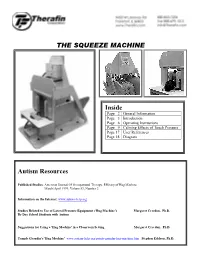

Squeeze Machine Indepth Information

THE SQUEEZE MACHINE Inside Page 2 General Information Page 3 Introduction Page 6 Operating Instructions Page 9 Calming Effects of Touch Pressure Page 17 User References Page 18 Diagram Autism Resources Published Studies: American Journal Of Occupational Therapy, Efficacy of Hug Machine March/April 1999, Volume53, Number 2 Information on the Internet: www.autism-help.org Studies Related to Use of Lateral Pressure Equipment ('Hug Machine') Margaret Creedon, Ph.D. By Day School Students with Autism Suggestions for Using a 'Hug Machine' in a Classroom Setting Margaret Creedon, Ph.D. Temple Grandin's 'Hug Machine' www.autism-help.org/points-grandin-hug-machine.htm Stephen Edelson, Ph.D. Squeeze Machine Page 2 Questions and Answers Q How Big Is It? Crated for shipment, the machine is 65" tall, 65" long and 54" wide. Uncrated, it is 60" tall, 60" long, and 32" wide. Crated, the complete system with compressor weighs almost 350 pounds. Q Who Can Use It? The Squeeze Machine can be used by most people because it is adjustable in a number of ways. The machine has a series of slots and holes to allow approximately fourteen inches of adjustment in width at the base of the pads. There are also slots to adjust the headrest height... slides to adjust for differing head widths... and the hand control center is adjustable from side to side and from front to back. One set of pads is included, which will accommodate either children or adults. Q What Is It Made Of? The basic structure is constructed from thirteen-ply 3/4" birch plywood.