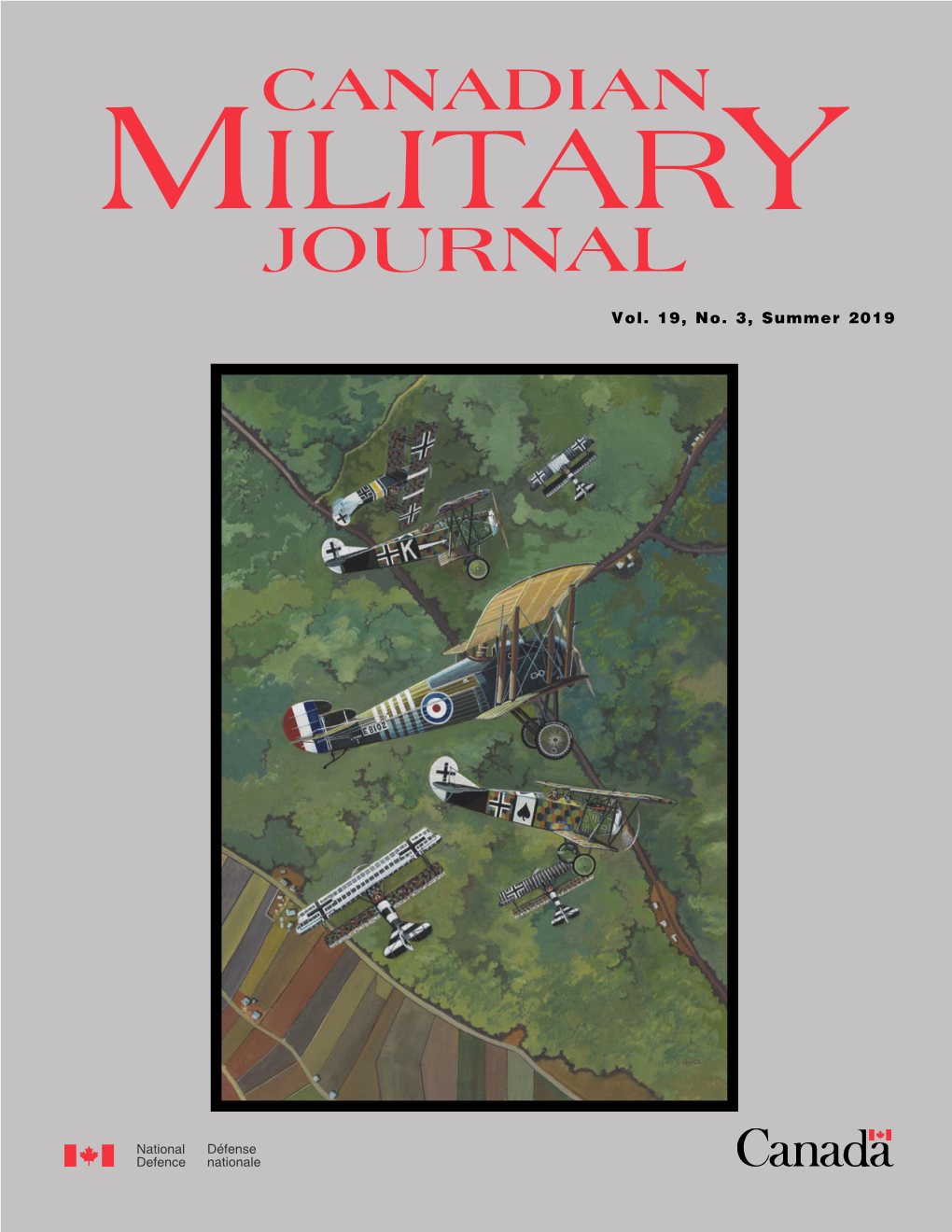

Canadian Military Journal

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Curling Canada • Ok Tire & Bkt Tires Continental Cup

CURLING CANADA • OK TIRE & BKT TIRES CONTINENTAL CUP, PRESENTED BY SERVICE EXPERTS HEATING, AIR CONDITIONING AND PLUMBING • MEDIA GUIDE 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS GENERAL INFORMATION BOARD OF GOVERNORS & NATIONAL STAFF 3 MEDIA INFORMATION 4 CURLING CANADA PHOTOGRAPHY GUIDELINES 5 TV NON-RIGHTS HOLDERS 6 EVENT INFORMATION FACT SHEET 7 SCHEDULE OF EVENTS 9 COMPETITION FORMAT & RULES 10 2020 OK TIRE & BKT TIRES CONTINENTAL CUP ANNOUNCEMENT 15 TEAMS & PLAYERS INFORMATION TEAM CANADA ROSTER 17 TEAM EUROPE ROSTER 17 PLAYER NICKNAMES 18 WOMEN’S PLAYER FACT SHEET 19 MEN’S PLAYER FACT SHEET 20 TEAM CANADA BIOS 21 TEAM CAREY 21 TEAM FLEURY 25 TEAM HOMAN 28 TEAM BOTTCHER 32 TEAM EPPING 35 TEAM KOE 39 TEAM CANADA COACH BIOS 43 TEAM EUROPE BIOS 46 TEAM HASSELBORG 46 TEAM MUIRHEAD 50 TEAM TIRINZONI 53 TEAM DE CRUZ 56 TEAM EDIN 59 TEAM MOUAT 63 TEAM EUROPE COACH BIOS 66 CURLING CANADA • OK TIRE & BKT TIRES CONTINENTAL CUP, PRESENTED BY SERVICE EXPERTS HEATING, AIR CONDITIONING AND PLUMBING • MEDIA GUIDE 2 BOARD OF GOVERNORS & NATIONAL STAFF CURLING CANADA 1660 Vimont Court Orléans, ON K4A 4J4 TEL: (613) 834-2076 FAX: (613) 834-0716 TOLL FREE: 1-800-550-2875 BOARD OF GOVERNORS John Shea, Chair Angela Hodgson, Governor Donna Krotz, Governor Amy Nixon, Governor George Cooke, Governor Cathy Dalziel, Governor Paul Addison, Governor Chana Martineau, Governor Sam Antila, Governor Mitch Minken, Governor NATIONAL STAFF Katherine Henderson, Chief Executive Officer Louise Sauvé, Administrative Assistant Bill Merklinger, Executive Director, Corporate Services Jacob Ewing, -

Chancellors Won't Be Denied After Magic

B2 n SPORTS THE BRANDON SUN n WEDNESDAY JANUARY 2 2019 » MIKE JONES TEAM OF THE YEAR WINNER Chancellors won’t be denied after magic run BY THOMAS FRIESEN It’s January, which means the Minnedosa Chancellors rugby team is kicking off its pre-season training. You read that right. If you wonder what it takes to become a provincial cham- pion, look no further than this group, which has taken home back-to-back high school pro- vincial titles in varsity girls’ 15s rugby. They also captured the Westman High School Rugby sevens crown with a 15-1 re- cord, playing as the Rivers Rams. The team was simply domi- nant all year and went unde- feated through the 15s season, beating the Dauphin Clippers in both the Westman High School Rugby final and the provincial title game. The group, which featured players from Minnedosa, Riv- ers, Erickson and Elton, is The Brandon Sun’s 45th an- nual Mike Jones team of the year, the first rugby squad to take home the award. The powerhouse squad was a three-plus-year project, and a testament to the work ethic The Minnedosa Chancellors rugby team have won back-to-back high school provincial titles in varsity girls’ 15s rugby. They are shown posing with the banner of the girls who first took to the at Crocus Plains in June. (Submitted) sport in Grade 9. Back then, head coach Kat Muirhead didn’t expect these PAST WINNERS titles to come the way they did. “I don’t think I thought un- 2018 — Minnedosa Chancellors/ 1997 — Neepawa Farmers, baseball defeated. -

Canadian Teams Open Universiade Curling Competition Monday in Almaty

Canadian teams open Universiade curling competition Monday in Almaty Jan 26, 2017 Canada’s reigning Canadian university curling champions will take aim at gold next week when the 2017 Winter Universiade curling competition gets underway Monday at the Almaty Arena in Almaty, Kazakhstan. Two-time World Junior Women’s Champion Kelsey Rocque will skip the Canadian women’s team from the University of Alberta in Edmonton, while Aaron Squires will be at the helm of the Canadian men’s team from the Wilfrid Laurier University Golden Hawks in Waterloo, Ont. Those teams won the right to represent Canada at the Winter Universiade by winning the gold medals at the 2016 CIS-Curling Canada Canadian University Curling Championships last March in Kelowna, B.C. Team Rocque (vice-skip Danielle Schmiemann, second Taylor McDonald, lead Taylore Theroux and coach Garry Coderre) will get things going in the 10-team women’s round robin on Monday at 9 a.m. local time (10 p.m. EST Sunday night) against China. Rocque won gold at the 2014 and 2015 World Juniors with different lineups; McDonald was a member of the 2014 team while Schmiemann won gold with Rocque a year later. Squires’ men’s team — the team is rounded out by vice-skip Richard Krell, second Spencer Nuttall, lead Fraser Reid and coach Jim Waite — will play the host country team from Kazakhstan in its opening game in the 10-team men’s competition on Monday at 2 p.m. local time (3 a.m. EST). At this point, only Canada’s team lineups are public knowledge; countries aren’t required to submit their official lineups until the team meeting on Saturday. -

Media Reportанаstatistical Report for Draw 3

Canadian Curling Association Men 2011 Canada Cup of Curling Presented by St. Eugene Cranbrook Rec Plex, Cranbrook, BC Media Report Statistical Report for Draw 3 Game Scores for Draw 3 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 TOTAL B Team McEwen 0 0 0 2 0 0 0 X X X 2 12:09 Team Stoughton *2 0 1 0 1 1 2 X X X 7 11:18 C Team Howard 1 0 1 0 0 3 0 0 2 0 7 03:04 Team Laycock *0 2 0 2 1 0 0 3 0 1 9 01:00 D Team Koe 0 2 0 2 0 1 0 0 1 1 7 02:07 Team Martin *1 0 2 0 2 0 2 1 0 0 8 03:16 *last rock advantage Team Standings After 3 Draw(s) Future Games Team Wins Losses 4 5 6 Team Martin 2 0 JAC HOW Team Stoughton 2 0 LAY KOE Team Laycock 1 1 STO MCE Team Koe 1 1 JAC STO Team Howard 1 1 MCE MAR Team McEwen 0 2 HOW LAY Team Jacobs 0 2 MAR KOE Draw Draw 4: 12/01 9:00 Draw 5: 12/01 14:00 Draw 6: 12/01 19:00 Times Attendance Draw 3: 0 Total: 0 Scoring and Percentages Summary for Draw 3 Draw 3 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 TOTAL B Team McEwen 0 0 0 2 0 0 0 X X X 2 12:09 Team Stoughton *2 0 1 0 1 1 2 X X X 7 11:18 MCE #SH PTS PCT STO #SH PTS PCT 1 Denni Neufeld 14 49 88 1 Steve Gould 14 56 100 2 Matt Wozniak 14 45 80 2 Reid Carruthers 14 43 77 © COPYRIGHT 2009 CANADIAN CURLING ASSOCIATION. -

Friends Search for Sladjana

Minister to hear foster concerns GNWT says Diane Thom will meet with foster care coalition representatives Online first at NNSL.com Where the future of NWT squash can shine Volume 48 Issue 85 WEDNESDAY, JANUARY 22, 2020 75 CENTS ($1 outside city) Friends search for Sladjana At your service News RCMP boss Alt North A member of the Yellowknife Community supports Foundation's Odd Job Squad installs a billboard is the bearing missing Sladjana Petrovic's face officer Monday. The signs are funded by Yellowknife 'unofficial Centre MLA Julie Green, Val Braden and Crime who drew Stoppers. "People have volunteered to help in opposition' anyway they can," says Green. weapon Photo courtesy of YKCF $1.00 outside Yellowknife Publication mail Contract #40012157 "We can't thank Overlander Sports enough for this machine." 7 71605 00100 5 – Rodney Taparti, recreation coordinator in Naurjaat, NT, which is receiving a used skate sharpener, page 3. 2 YElloWKNIFER, Wednesday, January 22, 2020 news YElloWKNIFER, Wednesday, January 22, 2020 3 Did we get it wrong? Yellowknifer is committed to getting facts and names right. With that goes a commitment to acknow- ledge mistakes and run corrections. If you spot an error in Yellowknifer, call 873-4031 and ask to speak to an editor, or email [email protected]. We'll get a correction or clarification in as soon as we can. NEws Briefs Theft reported at Sam’s Monkey Tree Pub Police are investigating a reported break-in and theft at Sam’s Monkey Tree Pub. Yellowknife RCMP received a report about a break and enter at the Range Lake Road res- taurant and bar just before 11 a.m. -

Extra-End-2016-2017

2016 - 2017 The official publica T ion of T he season of champions chelsea carey team Koe achieves life-long dream brushing aside hits its stride The conTroversy EE17_Cover.indd 1 2016-09-15 10:46 AM 2016 - 2017 The official publica T ion of T he season of champions 2017 Editor a q&a with curling canada’s tim hortons Brier 38 Laurie Payne katherine henderson 5 Alberta’s Kevin Koe wins seven straight Managing editor to capture his third title in seven years Al Cameron acknowledgments 6 ford world women’s 42 Art director curling canada Skip Binia Feltscher claims Otto Pierre Board of governors 7 Switzerland’s third straight gold medal Production director season of champions contacts 9 world men’s 44 Marylou Morris Team Canada’s Kevin Koe team koe hits its stride 10 ends gold-medal dry spell Printer In only their second year together St. Joseph Printing they’re the best in the world a salute to champions 46 by Con Griwkowsky Here’s to the teams that won Cover photography 2016 national and world titles Canada’s world men’s champions on the rocks 13 by Richard Gray and Céline Stucki, WCF Under-18 championships will fill a gap from the hack Photography in our system to develop young curlers to the Broadcast Booth 48 Michael Burns by Al Cameron Olympic silver medallist Cheryl Bernard is finding her voice as a TSN colour analyst Scotties Tournament of Hearts ford hot shots 14 by George Johnson photography Big prizes for winners Andrew Klaver in individual skills contests in the news 52 Congrats to annual award winners National sponsorship sales director let’s get more kids curling! 17 and Hall of Fame inductees David Beesley New donor-funded program Chief executive officer builds on the success of Rocks & Rings the ma cup 56 Katherine Henderson A new ranking system generates Brushing aside the controversy 18 greater interest among curling fans The wild-west era of brooms is over thanks, in part, to an off-season sweeping summit comBining education and curling 57 Extra End magazine is published by by Don Landry Scholarships help further athletic Curling Canada. -

Winkler Voice 020818.Indd

Automotive Glass Chip Repairs PRIMER SALE ON NOW Tinting Farm Equipment SuperSpec latex drywall primer Auto Accessories NOW ONLY $ 204-325-8387 150C Foxfi re Trail Winkler, MB (204)325-4012 79.99 per 5 gal. pail 600 Centennial St., Winkler, MB Winkler Morden VOLUME 9 EDITION 6 THURSDAY, FEBRUARY 8, 2017 VVLocally ownedoiceoice & operated - Dedicated to serving our communities Off to the Brier PHOTO BY RICK HIEBERT/VOICE Reid Carruthers, Braeden Moskowy, Derek Samagalski, and Colin Hodgson had a perfect week at the 2018 Viterra Championships in Winkler, going 6-0 heading into the fi nal game against Team McEwen and then winning the championship fi nal 7-6 to earn the right to represent Manitoba at the national men’s curling championships in Regina next month. See inside for more Viterra coverage. news > sports > opinion > community > people > entertainment > events > classifi eds > careers > everything you need to know 2 The Winkler Morden Voice Thursday, February 8, 2018 Carruthers defeats McEwen in Viterra championship fi nal By Ashleigh Viveiros time we had mentioned in the meet- ing that we might see him,” said Car- The 2018 Viterra Provincial Men’s ruthers, whose team had been fl aw- Curling Championship ended with a less with six wins heading into the clash of the titans. fi nal. Team McEwen, meanwhile, The top-seeded Mike McEwen and skipped by third B.J. Neufeld for Reid Carruthers faced off at the fi nals much of the week, had conceded to in Winkler Sunday afternoon. Carruthers 7-3 in the 1-2 qualifi er be- After falling to McEwen in the cham- fore beating out Team J.T. -

12/2/20 Scots Wha Hae Newsletter

Newsletter • Volume 87, Number 1 • December 2, 2020 Email: [email protected] • Web: www.detroitcurlingclub.com Practice Ice Available! While regularly scheduled league play is paused, Michigan Department of Health CALENDAR and Human Services emailed us clarifying that under the current guidelines the ice may be used for practice. Only one athlete may be on the ice at a time, unless a Bonspiels & second athlete who is practicing is from the same household. Online signups for a Special Events 30-minute practice slots are available on a first-come, first serve basis. You can sign up for a slot here: https://signup.com/go/QWTjXad January 29–31, 2021 Groundhog Day Open We have a couple days and times available, but are looking for more volunteers to Bowling Green Curling Club at host the practice sessions. Board members, draw masters, rental instructors, USCA the Black Swamp Curling certified and SafeSport certified are all eligible. Please contact Stephanie Whitmore Center. $320 per team. 13 at [email protected] if you are interested in hosting a practice session. Keep spots still available ! a lookout on the SignUp page for more slots as more instructors sign up! Bowling Green Mixed Doubles Spiel *All future DCC bonpsiels have been postponed until April due to Covid-19 Several DCC members made a trip to the Black Swamp Curling Center in Bowling Green on the weekend of November 14th and 15th. Julie Benson and Bret Jackson precautions. Stay tuned for won the B event playing against Jeff Peplinski and his partner Lori Markham any new information and (Seattle). -

MEN - 2014 Home Hardware Canada Cup of Curling Camrose, Alberta

MEN - 2014 Home Hardware Canada Cup of Curling Camrose, Alberta TEAM AND PLAYER IDENTIFICATION 1 Team Cotter COT Vernon Curling Club Vernon, BC Player no. 1 - Rick Sawatsky normally throws lead rocks. Player no. 2 - Tyrel Griffith normally throws second rocks. Player no. 3 - Ryan Kuhn normally throws third rocks. Player no. 4 - Jim Cotter normally throws last rocks. Team Coach - Pat Ryan 2 Team Gushue GUS Bally Haly Golf & Curling Club St. John's, NL Player no. 1 - Geoff Walker normally throws lead rocks. Player no. 2 - Brett Gallant normally throws second rocks. Player no. 3 - Mark Nichols normally throws third rocks. Player no. 4 - Brad Gushue normally throws last rocks. 3 Team Howard HOW Penetanguishene Curling Club Penetanguishene, ON Player no. 1 - Craig Savill normally throws lead rocks. Player no. 2 - Jon Mead normally throws second rocks. Player no. 3 - Richard Hart normally throws third rocks.(LH) Player no. 4 - Glenn Howard normally throws last rocks. Team Coach - Rob Meakin 4 Team Jacobs JAC Soo Curlers Association Sault Ste. Marie, ON Player no. 1 - Ryan Harnden normally throws lead rocks. Player no. 2 - E.J. Harnden normally throws second rocks. Player no. 3 - Ryan Fry normally throws third rocks. Player no. 4 - Brad Jacobs normally throws last rocks. 5 Team Koe KOE The Glencoe Club Calgary, AB Player no. 1 - Ben Hebert normally throws lead rocks. Player no. 2 - Brent Laing normally throws second rocks. Player no. 3 - Marc Kennedy normally throws third rocks.(LH) Player no. 4 - Kevin Koe normally throws last rocks. Team Coach - John Dunn 6 Team McEwen MCE Fort Rouge Curling Club Winnipeg, MB Player no. -

150 Notable Manitoba Curling Teams

150 NOTABLE MANITOBA CURLING TEAMS In honour of Manitoba’s 150 th Anniversary, the Manitoba Curling Hall of Fame and Museum has undertaken to identify 150 teams which played a significant role in creating (in the early years) and extending (in more recent times) Manitoba’s reputation for competitive excellence in the world of curling. Our list acknowledges teams from all competitive sectors from the high-profile junior and men’s and women’s teams to less well-known teams at the mixed, senior, and masters levels and even outside the association realm in the deaf, police and postal championship realms. All of these successful teams played roles in establishing Manitoba’s well-deserved reputation. We also acknowledge recent successes in the new discipline of Mixed Doubles but this historical perspective is focussed on the traditional four-person game. INVITATION TO THE PUBLIC TO ADD TO THE LIST: A total of 150 teams were identified initially. Subsequently two missed teams have been added so the list now includes 152 teams. There are many other teams across Manitoba’s curling history which also belong on a listing of this nature. Manitoba curling fans are invited to suggest other teams for inclusion. In most cases, the teams are included on this list on the basis of the team’s on-ice success in a single outstanding year OR across a series of years. In the latter case, we have acknowledged that so long as three people remained on a team from a previous recorded success – then it was still the same team. -

February More on This Year's Scotties and Brier

The Hack & Back October Club Executive February More on this year’s Scotties and Brier News that Curling Canada has officially announced it is looking at 18- Club Executive team fields for the Tim Hortons Brier and Scotties Tournament of President Hearts this year was met with applause by teams that were worried Calum McGeachie about being left on the outside, looking in, at the Calgary bubble. “It president@ferguscurlingclub does appear to be great news,” Winnipeg skip Mike McEwen said Wednesday. “We’ll just have to wait a little longer for the official in- Vice-President vite in black and white. We’re amazed at the extent Curling Canada and TBA its partners have gone to identify the need for a small expansion.” In recent years, the Brier and Scotties have been played with 16-team Past-President fields, which include representation from 14 member associations, the Bonnie Talbot returning champion (Team Canada) and one wild-card team, which is determined by a wild-card game on the night before the event begins. Treasurer Because of the COVID-19 pandemic, the curling season in Canada has Steve Graham been completely disrupted, but Curling Canada has announced plans to play major championships in a bubble environment in Calgary, starting Secretary on Feb. 20. Deb Wilson Different thinking was needed to fill out the fields for those events because many provinces and territories have cancelled their provincial Club Directors championships and are naming last year’s winners as representatives. Dale Beirnes Curling Canada is now saying that all 14 provinces and territories will Richard Booy be represented — there was a concern that some wouldn’t be able to John Ferguson send teams — and each event’s Team Canada (skipped by Newfoundland Brian Gibbon and Labrador’s Brad Gushue, and Gimli, Man.’s Kerri Einarson) are Bob Grant ready to participate as well. -

Manitoba Honour Roll

Manitoba Honour Roll YEAR CLUB SKIP THIRD SECOND LEAD BRITISH CONSOLS TROPHY 1925 Granite Howard Wood Sr. Victor Wood John Erzinger Lionel Wood 1926 St. John’s George Sherwood Charlie Edge Lionel Tinling Rod Vincent 1927 Granite Jim Congalton Jack Campbell Bill Noble Dr. Bill Sharman 1928 Strathcona Gordon M. Hudson Sam Penwarden Ron Singbush Bill Grant 1929 Strathcona Gordon M. Hudson Don Rollo Ron Singbush Bill Grant 1930 Granite Howard Wood Sr. Jim Congalton Victor Wood Lionel Wood 1931 Strathcona Robert Gourley Ernie Pollard Arnold Lockerbie Ray Stewart 1932 Granite Jim Congalton Jack Campbell Bill Noble Harry Mawhinney 1933 Deer Lodge John Douglas James Welsh Alex Welsh Jock Reid 1934 Strathcona Leo Johnson Lorne Stewart Lincoln Johnson Marno Frederickson 1935 Killarney Roy Pritchard George Ellis Arthur Boyce Mark Teskey 1936 Strathcona Ken Watson Grant Watson Marvin Macintyre Charles Kerr 1937 Deer Lodge James Welsh Fred Smith Jock Reid Harry Monk 1938 Glenboro Ab Gowanlock Bung Cartmell Bill McKnight Tom McKnight 1939 Strathcona Ross Kennedy Wm. MacDonald Robert Hume Clare Wells 1940 Granite Howard Wood Sr. Ernie Pollard Howard Wood Jr. Roy Enman 1941 Strathcona Albert Wakefield Doug Adams Lionel Francis Winston Anders 1942 Strathcona Ken Watson Grant Watson Chas. Scrymgeour Jim Grant 1943 Strathcona Ken Watson Grant Watson Chas. Scrymgeour Lyle Dyker 1944 Strathcona Leo Johnson Harry Weremy Bob Noble Jack Price 1945 Granite Howard Wood Sr. Al Derrett Lionel Wood Verne Handford 1946 Strathcona Leo Johnson Harry Weremy Lincoln Johnson Bill McKnight 1947 Deer Lodge Jim Welsh Alex Welsh Jock Reid Harry Monk 1948 Granite George Sangster Bill Sangster George Anderson Bill Petrie 1949 Strathcona Ken Watson Grant Watson Lyle Dyker Charles Read 1950 Elmwood Dr.