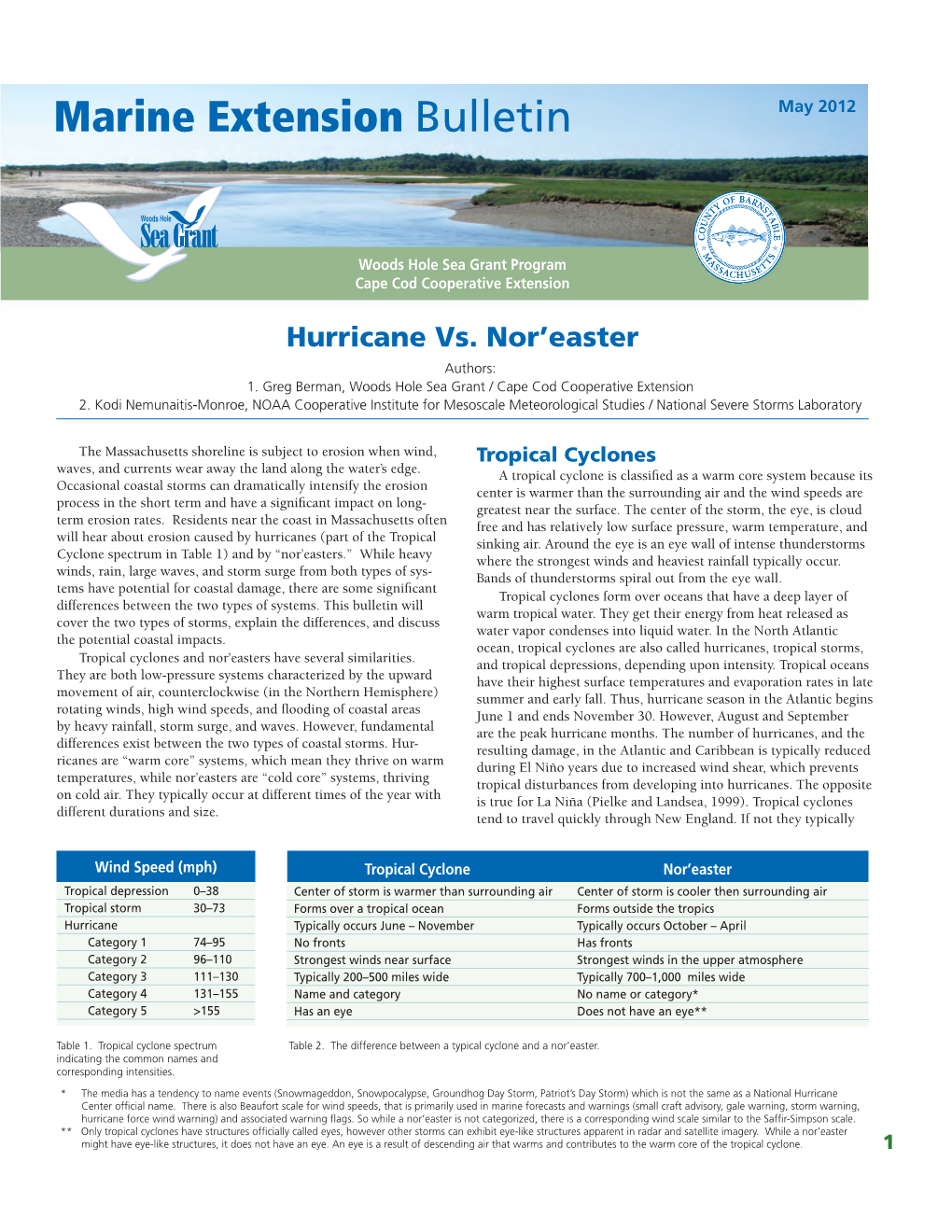

Hurricane Vs. Nor'easter

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Flood Mitigation and Sea Level Rise Adaptation for Kiawah Island: a Report

Flood Mitigation and Sea Level Rise Adaptation for Kiawah Island: A Report Story and photographs by Jack Kotz unny day or nuisance flooding is a relatively new term for most of us. As we described in the Winter/Spring 2018 issue of Naturally Kiawah, it refers to temporary flooding of low-lying areas in the absence of any precipitation or storm impacts, usually occurring during new or full moons. The higher than usual tides during these lunar periods are called “spring Stides.” Several times a year, when the new or full moon is closest to the Earth (at its perigee), the gravitational force is even greater. This causes a “king tide” or a “perigean spring tide” that often results in nuisance flooding. 16 The problem for Charleston and other coastal cities, as annual flooding. He estimates that in the next 50 years flooding well as Kiawah Island, is that the number of nuisance floods will be experienced by 15 percent of the buildings in the area. is increasing. In the 1970s there were only about two days On Kiawah, we experienced 16–20 inches of rainfall over a each year with nuisance floods in Charleston, whereas in 2015 four-day period in the 2015 rain event, and at least 42 percent Charleston had 38 days of tidal flooding, and in 2016 there of the land area of the Island was flooded. During Hurricane were 50 days of flooding. It is predicted there could be as Matthew in 2016, the storm tide was 3.5 feet above MHHW many as 180 days of flooding per year in the 2040s. -

The 17-Year Cycle & Energy II

© ITTC - INSIIDE Track Report The 17-Year Cycle & Energy II May 2008 “...Let us run with patience the race that is set before us.” Hebrews 12:1 by Eric S. Hadik The 17-Year Cycle & Energy II An INSIIDE Track Report “When you hear May 2008 - The last week has 17-Year Cycle & Energy II of wars and revolu- seen major reinforcements of the tions, do not be fright- 17-Year Cycle. On May 1st, a INSIIDE Track Report ened. These things major volcanic eruption in Chile must happen first, occurred, reinforcing the escalating C ONTENTS ...‘Nation will rise earth-disturbance cycles projected against nation, and Atmospheric Energy........................1 kingdom against king- for 2008. More recently, a 6.8 dom. magnitude earthquake rocked Jan- The Perfect Storm............................1 pan, just 100 miles from Tokyo. As There will be great stated in the May 7th Alert: Culmination of ‘Energy’ II.................6 earthquakes, famines & pestilences in vari- “Though these events are sig- ous places and fearful nificant, they are not of the magni- events and great signs tude that would make me believe from heaven. they have fulfilled the potential for ...There will be signs in the sun, moon and stars. On the earth, major earth disturbances in this nations will be in anguish and perplexity at the roaring and tossing of period.” the sea. Men will faint from terror, apprehensive of what is coming on the world for the heavenly bodies will be shaken.” So, more is expected. Luke 21: 9-11, 20, 25-26 Atmospheric Energy (New Int’l Vers. -

Basics of Tide & Tide Forecasting

Basics of tide & tide forecasting K. Srinivas Ocean State Forecast Lab (ISG) INCOIS, Hyderabad E-mail: [email protected] Phone: 040-23886057 040-23895017 Time and TIDE wait for none !!! Tides are an important physical forcing on the ocean particularly the coastal and estuarine seas ! Tide is the periodic rise and fall of a body of water due to gravitational interactions between the sun, moon and Earth Different positions of the sun and moon create two different types of tides: spring tides and neap tides Residual force is the difference between the gravitational force and centrifugal force They are very important for a proper understanding of : physics, chemistry, biology and geology of the coastal and estuarine waters The same location in the High Tide Low Tide Bay of Fundy at low and high tide. The maximum tidal range is approximately 17m The tidal range is the vertical difference between the low tide and the succeeding high tide. High Tide April 20, 2001 Low Tide September 30, 2002 Tidal extremes - The Bay of Fundy Vegetation is green, and water ranges from dark blue (deeper water) to light purple (shallow water) Tides at Halls Harbour on Nova Scotia's Bay of Fundy. This is a time lapse of the tidal rise and fall over a period of six and a half hours. There are two high tides every 25 hours. Presence of tide The most obvious indication of the presence of tide at any location (coastal or deep sea) is a characteristic, sinusoidal oscillation in the water level/ pressure records, containing either two main cycles per day (semidiurnal tides), one cycle per day (diurnal tides), or a combination of the two (mixed tides). -

Development of an Updated Coastal Marine Area Boundary for the Auckland Region

Development of an updated Coastal Marine Area boundary for the Auckland Region Prepared for Auckland Council July 2012 Authors/Contributors : Scott Stephens Sanjay Wadhwa For any information regarding this report please contact: Scott Stephens Coastal Scientist Coastal and Estuarine Processes +64-7-856 7026 [email protected] National Institute of Water & Atmospheric Research Ltd Gate 10, Silverdale Road Hillcrest, Hamilton 3216 PO Box 11115, Hillcrest Hamilton 3251 New Zealand Phone +64-7-856 7026 Fax +64-7-856 0151 NIWA Client Report No: HAM2012-111 Report date: July 2012 NIWA Project: ARC13233 © All rights reserved. This publication may not be reproduced or copied in any form without the permission of the copyright owner(s). Such permission is only to be given in accordance with the terms of the client’s contract with NIWA. This copyright extends to all forms of copying and any storage of material in any kind of information retrieval system. Whilst NIWA has used all reasonable endeavours to ensure that the information contained in this document is accurate, NIWA does not give any express or implied warranty as to the completeness of the information contained herein, or that it will be suitable for any purpose(s) other than those specifically contemplated during the Project or agreed by NIWA and the Client. Contents Executive summary .......................................................................................................................7 1 Introduction ........................................................................................................................9 -

Quincy Report

2019 GREATEST FLOOD RISK: HISTORICAL FLOOD EVENTS SEVERE WINTER • 9/1938 “The Great New England Hurricane” 10-17 inches of rain and 20-foot storm surge WEATHER COASTAL EROSION • 2/1978 “Blizzard of ’78” 30 inch snowfall, 30-foot waves off shore 24 RL claims COASTAL AND INLAND FLOODING • 10/1991 “Perfect Storm” 25 foot waves coincided with high tide 69 RL claims NOR’ EASTERS • 4/2010 “Nor’easter” 7 inches rain, coastal flooding and high tide. 52 RL claims • 1/2018 Nor’easter “Greyson” Peak winds coinciding with high tide broke Boston Harbor 1978 high tide record. • 3/2018- Nor’easters “Riley & Skylar” Blizzard, high wind and storm surge. FEMA DR-4372/ 4379 2) Identify Risk from “All Hazards” TOP NATURAL HAZARD RISKS FOR QUINCY image sample Coastal Flooding Flood Inland Flooding Storms and Tides Related Culvert Failures Storm Surge Sea Level Rise Climate Severe Snow and Blizzards Change Winter Extreme Precipitation Ice Storms Hurricanes Coastal Climatic Nor’easters Related Erosion & Shoreline Change Tropical Storm Tsunami Urban Fire Fire Earthquake Geologic Wildfire Landslides High Wind Severe Extreme Temperature (Heat and Cold Tornado Weather Drought Thunderstorm AREAS OF FLOODING CONCERNS FEMA REPETITIVE LOSS CLAIMS RL HOUGHS NECK GERMANTOWN RL FURNACE BROOK Identify extent & magnitude of flooding from tides, storm surge, and sea level rise… CLIMATE CHANGE FLOODING IMPACTS • Recommended approach for sea level rise estimates for projecting future coastal flooding risk in Quincy MA Sea Level Rise Time Period Projection² Likely Range³ (Feet) -

America's Perfect Storm

Policy Information Report America’s Perfect Storm Three Forces Changing Our Nation’s Future This.report.was.written.by: Irwin Kirsch, Henry Braun, and Kentaro Yamamoto of ETS, and Andrew Sum of Northeastern Table of Contents University. The.views.expressed.in.this.report. are.those.of.the.authors.and.do.not. necessarily.reflect.the.views.of.the. Preface....................................................................................................2 officers.and.trustees.of.Educational. Testing.Service. Acknowledgments..................................................................................2 Additional.copies.of.this.report.can. be.ordered.for.$15.(prepaid).from: Executive.Summary...............................................................................3 Policy.Information.Center. Introduction............................................................................................6 Mail.Stop.19-R. Educational.Testing.Service. A.Look.Backward...................................................................................8 Rosedale.Road. Princeton,.NJ.08541-0001. The.Three.Forces..................................................................................11 (609).734-5949. [email protected] The.Divergent.Skill.Distributions........................................................12 View.and.download.the.. The.Economy........................................................................................16 report.and.additional.materials.. at.ets.org/stormreport The.Demographic.Trends.....................................................................19 -

Section 4: Hazard Identification and Risk Assessments February 2016 Section 4: Hazard Identification and Risk Assessments

Section 4: Hazard Identification and Risk Assessments February 2016 Section 4: Hazard Identification and Risk Assessments 2016 Plan Update changes: This section combines Sections 6 and 7 into one section. Where possible, the content has been updated to reflect the best data available. 4.1 Introduction During the 2016 Plan update many parts of the original County HMP were preserved. Where applicable, portions of the historical hazard data have been retained. This section addresses the specific requirements of the Interim Final Rule (IFR) and FEMA checklist requirements (Local Mitigation Plan Review Tool, October, 2011) with regard to hazards in the planning area. As required by federal planning guidelines, one of the key elements of the 2016 HMP update was to describe the events and effects of natural hazards on the County since the original version of the Plan was developed and adopted in 2010. In addition detailed risk assessments were completed for all hazards ranked high (hazards of concern) or medium by the 2016 Hazard Mitigation Planning Steering Committee (HMPSC). The term “planning area” is used frequently in this section. This term refers to the jurisdictional limits of Middlesex County. The Risk Assessment section addresses the potential future damages from hazards on Middlesex County and its citizens. 4.1.1 Summary Description of the County’s Vulnerability to Hazards The DMA 2000 legislation and related FEMA planning guidance require mitigation plans to include discussion of community vulnerability to natural hazards. Vulnerability is generally defined as the damage (including direct damages and loss of function) that would occur when various levels of hazards impact a structure, operation or population. -

MASARYK UNIVERSITY BRNO Diploma Thesis

MASARYK UNIVERSITY BRNO FACULTY OF EDUCATION Diploma thesis Brno 2018 Supervisor: Author: doc. Mgr. Martin Adam, Ph.D. Bc. Lukáš Opavský MASARYK UNIVERSITY BRNO FACULTY OF EDUCATION DEPARTMENT OF ENGLISH LANGUAGE AND LITERATURE Presentation Sentences in Wikipedia: FSP Analysis Diploma thesis Brno 2018 Supervisor: Author: doc. Mgr. Martin Adam, Ph.D. Bc. Lukáš Opavský Declaration I declare that I have worked on this thesis independently, using only the primary and secondary sources listed in the bibliography. I agree with the placing of this thesis in the library of the Faculty of Education at the Masaryk University and with the access for academic purposes. Brno, 30th March 2018 …………………………………………. Bc. Lukáš Opavský Acknowledgements I would like to thank my supervisor, doc. Mgr. Martin Adam, Ph.D. for his kind help and constant guidance throughout my work. Bc. Lukáš Opavský OPAVSKÝ, Lukáš. Presentation Sentences in Wikipedia: FSP Analysis; Diploma Thesis. Brno: Masaryk University, Faculty of Education, English Language and Literature Department, 2018. XX p. Supervisor: doc. Mgr. Martin Adam, Ph.D. Annotation The purpose of this thesis is an analysis of a corpus comprising of opening sentences of articles collected from the online encyclopaedia Wikipedia. Four different quality categories from Wikipedia were chosen, from the total amount of eight, to ensure gathering of a representative sample, for each category there are fifty sentences, the total amount of the sentences altogether is, therefore, two hundred. The sentences will be analysed according to the Firabsian theory of functional sentence perspective in order to discriminate differences both between the quality categories and also within the categories. -

Hazard Mitigation Plan

Source: Wikimedia Town of Savoy, MA HAZARD MITIGATION PLAN April 2021 Prepared by: westonandsampson.com SAVOY, MA Hazard Mitigation Plan TABLE OF CONTENTS Page 1.0 INTRODUCTION..........................................................................................................1-1 1.1 What is a Hazard Mitigation Plan?............................................................................1-1 1.2 Hazard Mitigation Planning in Savoy ........................................................................1-2 1.3 Planning Process Summary .....................................................................................1-3 1.3.1 Core Team ...........................................................................................................1-3 1.3.2 Stakeholder Involvement ......................................................................................1-5 1.3.3 Plan Layout ..........................................................................................................1-5 1.4 Planning Timeline.....................................................................................................1-5 2.0 HAZARD MITIGATION GOALS ...................................................................................2-6 3.0 COMMUNITY PROFILE, LAND USE, AND DEVELOPMENT TRENDS.......................3-1 3.1 Community Profile ....................................................................................................3-1 3.2 Land Use..................................................................................................................3-4 -

What Is High Tide Flooding?

https://oceanservice.noaa.gov/facts/high-tide-flooding.html%20 Examples of why Highway 80 going out to Tybee Islands floods and low-lying areas throughout Savannah where the coastal waters connect with elevations near 6 NAVD 1988. National Ocean ServiceNational Oceanic and Atmospheric AdministrationU.S. Department of Commerce SearchSearch National Ocean Service • HOMEHome 1. Facts 2. What is high tide flooding? What is high tide flooding? High tide flooding—flooding that leads to public inconveniences such as road closures — is increasingly common as coastal sea levels rise. High tide flooding events have increased around the U.S., but especially off the East Coast. To down load the image click on: | Download PDF As relative sea level increases, it no longer takes a strong storm or a hurricane to cause coastal flooding. Flooding now occurs with high tides in many locations due to climate- related sea level rise, land subsidence, and the loss of natural barriers. High tide flooding — which causes such public inconveniences as frequent road closures, overwhelmed storm drains and compromised infrastructure — has increased in the U.S. on average by about 50 percent since 20 years ago and 100 percent since 30 years ago. The effects of rising sea levels along most of the continental U.S. coastline are expected to become more noticeable and much more severe in the coming decades, likely more so than any other climate-change related factor. Any acceleration in sea level rise that is https://oceanservice.noaa.gov/facts/high-tide-flooding.html%20 predicted to occur this century will further intensify high tide flooding impacts over time, and will further reduce the time between flood events. -

INTERNAL DOCUMENT Tide, Surge and Still Water Levels at Chesil Beach. Graham Alcock. Institute of Oceanographic Sciences Bidston

INTERNAL DOCUMENT 2/0 Tide, Surge and Still Water Levels at Chesil Beach. Graham Alcock. Institute of Oceanographic Sciences Bidston Observatory Birkenhead. June 1984. [This document should not be cited in a published bibliography, and is supplied for the use of the recipient only]. INSTITUTE OF \ OCEANOGRAPHIC SCIENCES ''loi INSTITUTE OF OCEANOGRAPHIC SCIENCES Wormley, Godalming, Surrey GU8 5UB (042-879-4141) (Director: Dr. A. S. Laughton) Bidston Observatory, Crossway, Birkenhead, Taunton, Mersey side L43 7RA Somerset TA1 2DW (051-653-8633) (0823-86211) (Assistant Director: Dr. D. E. Cartwright) (Assistant Director: M.J. Tucker) \ Tide, Surge and Still Water Levels at Chesil Beach. Graham A1cock. Institute of Oceanographic Sciences Bidston Observatory Birkenhead. June 1984. Internal Document No. 210. "This information or advice is given in good faith and is believed to be correct, but no responsibility can be accepted by the Natural Environment Research Council for any consequential loss or damage arising from any use that is made of it." 1. Introduction C.H. Dobbie (CHD) are acting as Consulting Engineers on a project concerning shore processes and protection at Chesil Beach, in conjunction with the Department of Civil Engineering at Imperial College, Hydraulics Research Ltd., Wessex Water Authority and Ministry of Agriculture, Fisheries and Food. CHD need to supply HRS with estimates of still water level (i.e. tide + surge) during the flood events of 13 December 1978, 13 February 1979» 20 December 1983s and 26 January 1984. lOS were commissioned by CHD to provide and prepare a pressure gauge for deployment off of Chesil Beach, to process and analyse the record to yield tide and surge statistics, and to hindcast levels for the flood events. -

Tide 1 Tides Are the Rise and Fall of Sea Levels Caused by the Combined

Tide 1 Tide The Bay of Fundy at Hall's Harbour, The Bay of Fundy at Hall's Harbour, Nova Scotia during high tide Nova Scotia during low tide Tides are the rise and fall of sea levels caused by the combined effects of the gravitational forces exerted by the Moon and the Sun and the rotation of the Earth. Most places in the ocean usually experience two high tides and two low tides each day (semidiurnal tide), but some locations experience only one high and one low tide each day (diurnal tide). The times and amplitude of the tides at the coast are influenced by the alignment of the Sun and Moon, by the pattern of tides in the deep ocean (see figure 4) and by the shape of the coastline and near-shore bathymetry.[1] [2] [3] Most coastal areas experience two high and two low tides per day. The gravitational effect of the Moon on the surface of the Earth is the same when it is directly overhead as when it is directly underfoot. The Moon orbits the Earth in the same direction the Earth rotates on its axis, so it takes slightly more than a day—about 24 hours and 50 minutes—for the Moon to return to the same location in the sky. During this time, it has passed overhead once and underfoot once, so in many places the period of strongest tidal forcing is 12 hours and 25 minutes. The high tides do not necessarily occur when the Moon is overhead or underfoot, but the period of the forcing still determines the time between high tides.