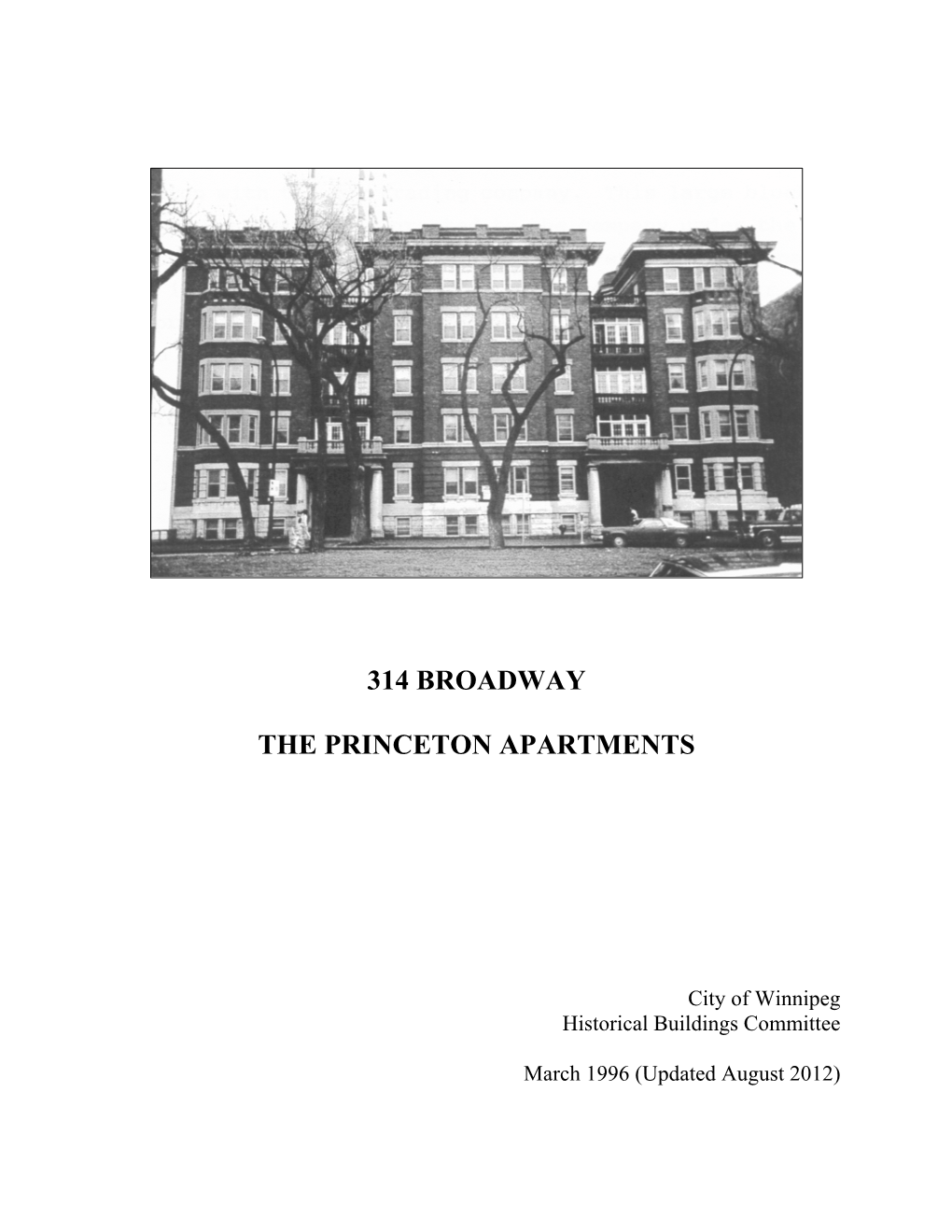

314 Broadway

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

20 Bus Time Schedule & Line Route

20 bus time schedule & line map 20 Academy-Watt View In Website Mode The 20 bus line (Academy-Watt) has 6 routes. For regular weekdays, their operation hours are: (1) Airport Terminal: 12:03 AM - 11:25 PM (2) Downtown: 6:22 PM - 7:03 PM (3) Fort & Portage: 12:20 AM - 12:56 AM (4) Henderson: 5:38 PM - 7:03 PM (5) Portage & Tylehurst: 12:25 AM - 12:52 AM (6) Watt & Leighton: 5:21 AM - 11:44 PM Use the Moovit App to ƒnd the closest 20 bus station near you and ƒnd out when is the next 20 bus arriving. Direction: Airport Terminal 20 bus Time Schedule 81 stops Airport Terminal Route Timetable: VIEW LINE SCHEDULE Sunday 7:07 AM - 5:43 PM Monday 5:22 AM - 11:25 PM Northbound Leighton at Leighton Loop Watt Street, Winnipeg Tuesday 12:03 AM - 11:25 PM Southbound Watt at Greene Wednesday 12:03 AM - 11:25 PM 495 Greene Ave, Winnipeg Thursday 12:03 AM - 11:25 PM Southbound Watt at Hazel Dell Friday 12:03 AM - 11:25 PM 495 Hazel Dell Ave, Winnipeg Saturday 12:03 AM - 11:57 PM Southbound Watt at Dunrobin 770 Watt St, Winnipeg Southbound Watt at Kimberly 722 Watt Street, Winnipeg 20 bus Info Direction: Airport Terminal Southbound Watt at Chelsea Stops: 81 496 Chelsea Ave, Winnipeg Trip Duration: 58 min Line Summary: Northbound Leighton at Leighton Southbound Watt at Sydney Loop, Southbound Watt at Greene, Southbound Watt 499 Sydney Ave, Winnipeg at Hazel Dell, Southbound Watt at Dunrobin, Southbound Watt at Kimberly, Southbound Watt at Southbound Watt at Neil Chelsea, Southbound Watt at Sydney, Southbound 635 Watt St, Winnipeg Watt at Neil, Southbound -

Directory – Indigenous Organizations in Manitoba

Indigenous Organizations in Manitoba A directory of groups and programs organized by or for First Nations, Inuit and Metis people Community Development Corporation Manual I 1 INDIGENOUS ORGANIZATIONS IN MANITOBA A Directory of Groups and Programs Organized by or for First Nations, Inuit and Metis People Compiled, edited and printed by Indigenous Inclusion Directorate Manitoba Education and Training and Indigenous Relations Manitoba Indigenous and Municipal Relations ________________________________________________________________ INTRODUCTION The directory of Indigenous organizations is designed as a useful reference and resource book to help people locate appropriate organizations and services. The directory also serves as a means of improving communications among people. The idea for the directory arose from the desire to make information about Indigenous organizations more available to the public. This directory was first published in 1975 and has grown from 16 pages in the first edition to more than 100 pages in the current edition. The directory reflects the vitality and diversity of Indigenous cultural traditions, organizations, and enterprises. The editorial committee has made every effort to present accurate and up-to-date listings, with fax numbers, email addresses and websites included whenever possible. If you see any errors or omissions, or if you have updated information on any of the programs and services included in this directory, please call, fax or write to the Indigenous Relations, using the contact information on the -

Municipal Officials Directory 2021

MANITOBA MUNICIPAL RELATIONS Municipal Officials Directory 21 Last updated: September 23, 2021 Email updates: [email protected] MINISTER OF MUNICIPAL RELATIONS Room 317 Legislative Building Winnipeg, Manitoba CANADA R3C 0V8 ,DPSOHDVHGWRSUHVHQWWKHXSGDWHGRQOLQHGRZQORDGDEOH0XQLFLSDO2IILFLDOV'LUHFWRU\7KLV IRUPDWSURYLGHVDOOXVHUVZLWKFRQWLQXDOO\XSGDWHGDFFXUDWHDQGUHOLDEOHLQIRUPDWLRQ$FRS\ FDQEHGRZQORDGHGIURPWKH3URYLQFH¶VZHEVLWHDWWKHIROORZLQJDGGUHVV KWWSZZZJRYPEFDLDFRQWDFWXVSXEVPRGSGI 7KH0XQLFLSDO2IILFLDOV'LUHFWRU\FRQWDLQVFRPSUHKHQVLYHFRQWDFWLQIRUPDWLRQIRUDOORI 0DQLWRED¶VPXQLFLSDOLWLHV,WSURYLGHVQDPHVRIDOOFRXQFLOPHPEHUVDQGFKLHI DGPLQLVWUDWLYHRIILFHUVWKHVFKHGXOHRIUHJXODUFRXQFLOPHHWLQJVDQGSRSXODWLRQV,WDOVR SURYLGHVWKHQDPHVDQGFRQWDFWLQIRUPDWLRQRIPXQLFLSDORUJDQL]DWLRQV0DQLWRED([HFXWLYH &RXQFLO0HPEHUVDQG0HPEHUVRIWKH/HJLVODWLYH$VVHPEO\RIILFLDOVRI0DQLWRED0XQLFLSDO 5HODWLRQVDQGRWKHUNH\SURYLQFLDOGHSDUWPHQWV ,HQFRXUDJH\RXWRFRQWDFWSURYLQFLDORIILFLDOVLI\RXKDYHDQ\TXHVWLRQVRUUHTXLUH LQIRUPDWLRQDERXWSURYLQFLDOSURJUDPVDQGVHUYLFHV ,ORRNIRUZDUGWRZRUNLQJLQSDUWQHUVKLSZLWKDOOPXQLFLSDOFRXQFLOVDQGPXQLFLSDO RUJDQL]DWLRQVDVZHZRUNWRJHWKHUWREXLOGVWURQJYLEUDQWDQGSURVSHURXVFRPPXQLWLHV DFURVV0DQLWRED +RQRXUDEOHDerek Johnson 0LQLVWHU TABLE OF CONTENTS MANITOBA EXECUTIVE COUNCIL IN ORDER OF PRECEDENCE ............................. 2 PROVINCE OF MANITOBA – DEPUTY MINISTERS ..................................................... 5 MEMBERS OF THE LEGISLATIVE ASSEMBLY ............................................................ 7 MUNICIPAL RELATIONS .............................................................................................. -

Gentrification in West Broadway?

Gentrification in West Broadway? Contested Space in a Winnipeg Inner City Neighbourhood By Jim Silver ISBN 0-88627-463-x May 2006 About the Author Jim Silver is a Professor of Politics at the University of Winnipeg, and a member of the Board of the Canadian Centre for Policy Alternatives. Acknowledgements For their various contributions to this project, I am grateful to Roger Barske, Nigel Basely, Ken Campbell, Paul Chorney, Matt Friesen, Linda Gould, Brian Grant, Rico John, Darren Lezubski, Jennifer Logan, John Loxley, Shauna MacKinnon, Brian Pannell, Boyd Poncelet, Bob Shere and Linda Williams. Thanks also to the University of Winnipeg for awarding a Major Research Grant that made research for this project possible. This report is available free of charge from the CCPA website at www.policyalternatives.ca. Printed copies may be ordered through the Manitoba Office for a $10 fee. CANADIAN CENTRE FOR POLICY ALTERNATIVES–MB 309-323 Portage Ave., Winnipeg, Manitoba, Canada R3B 2C1 PHONE (204) 927-3200 FAX (204) 927-3201 EMAIL [email protected] www.policyalternatives.ca/mb Contents 5 Introduction 7 1 Gentrification: A Brief Review of the Literature 12 2 The West Broadway Neighbourhood 18 3 The Dangers of Gentrification 20 4 Evidence of Gentrification in West Broadway 25 5 Why is Gentrification Occurring in West Broadway? 28 6 The Importance of Low-Income Rental Housing for West Broadway’s Future 31 7 Prospects for West Broadway 33 References GENTRIFicATION in WEST BROADWAY? Contested Space in a Winnipeg Inner City Neighbourhood By Jim Silver Since the mid-20th century, urban decline has rehabilitation of deteriorated but architecturally become almost ubiquitous in North American unique housing, stabilization of the population inner city neighbourhoods. -

2017 Manitoba's Local Produce Guide – Winnipeg

WINNIPEG 8 PERIMETER HWY 101 FARMERS’ MARKETS 117 98 Bronx Park Community Centre 204 100 Saturday Evan Comstock 204-510-7667 WINNIPEG ST 59 113 [email protected] LEILA AVE ST HWY www.bronxpark.ca CHIEF PEGUIS TRAIL 120 June 3 - September 30 INKSTER BLVD McPHILLIPS 9:00 a.m. to 2:00 p.m. BLVD 720 Henderson Hwy, main parking lot MAIN 101 99 Downtown Winnipeg Biz Thursday HENDERSON Susan Ainley204-958-4626 98 [email protected] 104 NOTRE DAME AVE www.facebook.com/dtwpgfarmersmkt Sturgeon 103 LAGIMODIERE June - September - outdoors NAIRN AVE October - May 2018 - indoors Creek REGENT AVE 112 10:00 a.m. to 3:00 p.m. RUE 105 106 MB Hydro Place Plaza, Graham Avenue at DUGALD RD 15 KING EDWARD ST 99 Edmonton Street, 360 Portage Avenue PORTAGE 114102 107 ARCHIBALD 100 East St. Paul Saturday AVE 115 119 Tyne Mills 204-668-8336 1 OSBORNE ST 118 [email protected] LAGIMODIERE CORYDON AVE 108 www.eaststpaul.com ROBLIN 111 BLVD June 17 - October 7 110 GRANT AVE 10:00 am - 2:00 pm BLVD The Market is located at 302 Hoddinott Rd in AVE WILKES East St. Paul, located adjacent to the East St. 1 Paul Arena and Curling Club. BLVDST ANNE’S RD KENASTON HWY 101 FortWhyte Farms Tuesday GRANDIN LAGIMODIERE FortWhyte Farms 204-895-2373 ST BISHOP RD MARY’S [email protected] 101 www.fortwhytefarms.com 59 July 4 - October 3 116 ST 12:00 p.m. to 6:00 p.m. BLVD PEMBINA (only until 5:00 pm starting In September) 100 Located in south west of Winnipeg at FortWhyte Alive - find us in the Farm buildings with the McGILLIVRAY red tin roof Oak WAVERLEY Bluff 109 102 Good Food Club Mini Market PERIMETER HWY Ailene Deller or Kelly Frazer 121 Farmers’ Market 204-774-7201 ext 6 [email protected] Pre-picked Market Stand www.westbroadway.mb.ca/good-food-club October - mid June every second Wednesday 3:00 p.m. -

Winnipeg Transit Long Term Network Plan | Primary Network Diagram

Winnipeg Transit Long Term Network Plan | Primary Network Diagram Service Overview I PRIMARY NETWORK Seven Oaks A Rapid Lines H Service every 5-10 minutes B ADSUM AVE GARDEN CITY High Frequency, high capacity transit service with C transit-only right of way where neededto bypass W congestion and move more quickly across the city. CHIEF PEGUIS I Frequent Lines W H Service every 10-15 minutes J E Frequent bus service running along major streets to MCPHILLIPS ST LEILA AVE K travel downtown or across the city. BURROWS AVE U H R Direct Lines N MCGREGOR ST KING EDWARD ST KING EDWARD W Q Service every 10-20 minutes Regular bus service running along major streets to ST KEEWATIN SELKIRK AVE U travel downtown or across the city. SALTER ST MCLEOD AVE Diagram Not to Scale I MAIN ST HENDERSON HWY RED RIVER ST MCPHILLIPS COLLEGE F NOTRE DAME AVE U GATEWAY RD Concordia J H WILLIAM AVE Health U Sciences TALBOT AVE O B H PANET RD - MOLSON ST HIGGINS NAIRN AVE J KILDARE AVE P WELLINGTON AVE H Red River Airport KILDONAN DAY ST T College CITY HALL SARGENT AVE PLACE K N C PORTAGE & MAIN PEGUIS ST PROVENCHER BLVD REGENT AVE ELLICE AVE L DONALD BLVD LAGIMODIERE UNION University EDMONTON G ST. JAMES ST ST. of Winnipeg COLONY The DES MEURONS ST Forks SHERBROOK ST SHERBROOK SPENCE STRADBROOK DUGALD RD Saint Boniface HAMILTON AVE BROADWAY H MARION ST NESS AVE T BUCHANAN BLVD Q RIVER AVE Misericordia H ST ARCHIBALD HARKNESS M P H Grace POLO PARK MORAY PORTAGE AVE H Assiniboia J Downs RD MARY’S ST. -

194 Broadway – Manitoba Club

194 BROADWAY – MANITOBA CLUB City of Winnipeg Historical Buildings & Resources Committee Researcher: M. Peterson August 2017 This building embodies the following heritage values as described in the Historical Resources By-law, 55/2014 (consolidated update July 13, 2016): (a) Built in 1905 with several pre-World War I additions, the Manitoba Club was an important facility locating on one of the City’s early signature thoroughfares, Broadway; (b) It is associated with the Manitoba Club, Western Canada’s oldest private clubs, whose member role includes some of the City and region’s most influential citizens; (c) It is an excellent example of the Neo-Classical or Classical Revival style and was designed by local architect S. Frank Peters; (d) It is built of dark brick with stone accenting on a stone foundation, all typical of the era; (e) It is a conspicuous building within the downtown; and (f) The building’s exterior has suffered little alteration. 194 BROADWAY – MANITOBA CLUB One of Winnipeg’s earliest and most exclusive residential districts was known as the Hudson’s Bay Reserve, so named because of its long association with the fur trading company. This large block of land, 188 hectares, near Upper Fort Garry was granted to the company under the terms of the surrender of the Company’s land rights in Western Canada (Rupert’s Land) to the Government of Canada. The Reserve included the land west of the Red River as far as Colony Creek (present-day Osborne Street) and from the Assiniboine River north to Notre Dame Avenue (Plate 1). -

Citizen Budget Submission on Infrastructure

If you would increase or decrease infrastructure investments, what would you change? Responses Focus on prevention. It may make sense to close some roads if we expanded some others. Move rail lines out of Winnipeg and increase population density, encourage public transit I would invest more in developing Manitoba infrastructure, roads, bridge's, etc. I would employee more workers that have been reliant on EIA and assign them a mentor for specific projects. This would assist them in getting out of EIA and into the workforce. Leave it as is. The rapid transit is a billion dollar mistake. It should have never been approved. That money would be better invested in fixing areas in the city with a crumbling infrastructure. More interchanges across the province, less gravel shoulders on highways. increased spending on infrastructure leads to more jobs, better quality of life. Lets face it our roads and infrastructure are in a poor state. Re-directing funds allocated for new projects/development into maintaining and improving existing infrastructure is crucial at this point. Change in how the province obtain private contractors' services. There are a lot of waste in infrastructure. For example, a road that was just repaired last year, they dug up again and put a substandard patch, which makes driving crazy. No funding until we can afford it. Make highway 75 a real highway that isn't being torn up and re done every summer. Get it done right and if it has to be re done the next summer go after the company performing the shoddy work. -

Fort Garry Campus Food Services

What’s Going On In Winnipeg? Folklorama Location: All Over Winnipeg! Telephone No.: (204) 982-6210 Folklorama is a 2 week multicultural festival celebrating the ethnic heritage of people who call Winnipeg home. It features 20 pavilions each week, with each pavilion showcasing the food, dance, music, dress and customs of a particular country. It’s an amazing time! Winnipeg Goldeyes Baseball Location: Canwest Park (1 Portage Avenue East) Telephone No.: (204) 982-2273 th th Watch the Winnipeg Goldeyes take on the Joliet JackHammers or Schaumburg Flyers in Northern League baseball action on August 6 to 9 . 1. Downtown & St. Boniface Portage Avenue Winnipeg Art Gallery Location: 300 Memorial Boulevard Telephone No.: (204) 786-6641 WAG, Manitoba’s premier gallery, features art from Canada and abroad. Current exhibitions include: Canada on Canvas: A Private Collection at The WAG, The Sterling Quality: Four Centuries of Silver, Allyson Mitchell: Ladies Sasquatch, Inuit Dolls of the Kivalliq and Joe Fafard. Broadway Dalnavert Museum Location: 61 Carlton Street Telephone No.: (204) 943-2835 Dalnavert Museum is the Victorian-era home of Sir Hugh John Macdonald, son of Sir John A. Macdonald, Canada’s first Prime Minister. Fort Garry Hotel Location: 222 Broadway Telephone No.: (204) 942-8251 Built in 1913, this château-style hotel is the ultimate in luxury. The hotel features a lavish health spa and decadent Sunday brunch. Manitoba Legislative Building Location: 450 Broadway Telephone No.: (204) 945-4243 The Manitoba Legislative Building, completed in 1920, is home to the Legislative Assembly of Manitoba and Manitoba’s famous Golden Boy. Upper Fort Garry Location: 212 Main Street (at the corner of Main Street and Broadway) Telephone No.: (204) 947-5073 Rebuilt in 1836, Upper Fort Garry – a Hudson’s Bay Company trading post – was the site of the Red River Resistance led by Louis Riel. -

Manitoba Designated Impacted Sites List

MANITOBA DESIGNATED IMPACTED SITES LIST Disclaimer This is a list is all sites that are currently designated as Impacted under the Contaminated Sites Remediation Act. A complete Environmental File Search is recommended to confirm all the information Manitoba Conservation and Climate maintains on a site. Sites listed here are also listed on List of all sites on file with The Contaminated/Impacted Sites Program. This list is found under the header Sites Lists on the Contaminated/Impacted Sites Program website at: https://www.gov.mb.ca/sd/waste_management/contaminated_sites/index.html As of April 6, 2021 MANITBA DESIGNATED IMPACTED SITES LIST File Site Name Address City/Town/RM Number 49792 MANITOBA HYDRO - POINTE DU BOIS 4.75 MILES WEST OF POINTE Alexander RAIL SPUR DU BOIS 54469 MANITOBA HYDRO - GREAT FALLS GS SE 35-17-11 E Alexander CONSTRUCTION DUMP 62524 SANDY BAY GAS BAR & CONVENIENCE HIGHWAY 50 AND MAIN Alonsa STORE ROAD 73453 IMPERIAL OIL BULK FACILITY 144 DEPOT STREET Alonsa 59283 WAIL INVESTMENTS LTD 207 CENTRE AVENUE Altona 62239 DOMO GASMART 273 CENTRE AVENUE EAST Altona 19433 ARBORG CO-OP - 328 MAIN ST 328 MAIN ST Arborg (FORMER BULK PLANT) 59619 IMPERIAL OIL BULK - ARBORG 441 MAIN ST Arborg 19516 ESSO BULK - ARNAUD NE 29-03-03 E, HWY 217 Arnaud 19491 LAKESIDE ESSO LTD 30 RAILWAY AVE Ashern 19505 IMPERIAL OIL RETAIL - ASHERN 13 HWY 6 Ashern (FORMER) 19676 FORMER PETRO-CANADA BULK PLANT, 109 3RD ST Beausejour BEAUSEJOUR 19986 ESSO BULK PLANT - BEAUSEJOUR 611 ATLANTIC AVE Beausejour (FORMER) 79905 RED LETTER VENTURES 733 PARK -

Downtown Winnipeg BIZ Indoor Walkway

GETTING AROUND DOWNTOWN ALL THINGS DOWNTOWN YOUR GUIDE TO DOWNTOWN TRENDS DOWNTOWNWINNIPEGTRENDS.COM Downtown is the most walkable neighbourhood in the city, with a diverse assortment of amenities/ services and public transportation in close proximity. (1) 1 BIKE RACKS ON BROADWAY Locals and tourists rate Winnipeg’s downtown as the top destination for arts, culture and entertainment! 50+ Festivals that draw more than a million visits annually Largest naturally frozen river trail in the world FARMERS’ 2 MANYFEST 2015 3 MARKET Hundreds of restaurants that delight the appetites of foodies Explore Winnipeg’s history - both past and future - at more than 5 museums and galleries, including the newly built Canadian Museum for Human Rights 4 WINTER RIVER TRAIL (1) www.walkscore.com GETTING AROUND DOWNTOWN Winnipeg Transit & Downtown Spirit Free Shuttle Bus Downtown Parking Buses run from approximately 5am to 2am on weekdays/ City of Winnipeg Street Parking Meters Saturdays and approximately 5:30am to 1am on Sundays Saturdays: 2 hours complementary Info: 311 | www.winnipegtransit.com Sundays: free parking Monday-Friday: 5:30pm-8am: free parking Winnipeg Transit Info Booths Monday-Friday: 8am-5:30pm: $1-2/hour “W” Portage & Main Concourse “W” Millennium Library Downtown Parkades & Parking Lots Maximum costs range from $4-$14 during the day, Catch the Free Spirit! and $1-$8 for evening. (Jets game nights: up to $20) Zip around downtown for free on the Downtown Spirit Hourly rates are between $1-$5. free shuttle bus. Catch the Spirit at regular bus stops. Winnipeg Parking Authority Active Transportation 311 | www.theparkingstore.winnipeg.ca Or travel on foot or by bike to your downtown destination for fun, fitness and fresh air. -

Road Trip Guide2021 / Insertion Date: ? Dinos Uncovered/ CMYK / 7 X 9.5 in Problems Or Questions Email [email protected] WINNIPEG’S ORIGINAL DOWNTOWN

Use this guide to customize your own day trips or overnight stays as you explore every corner of Manitoba. You can also extend these trips to add on other Manitoba destinations that are ready to welcome you. Hit the road and remember that home is where the heart is. ↑ Spruce Woods Provincial Park Festival Memories While care has been taken in the creation of this publication, the information in this publication comes Manitoba is known for its incredible festivals and events. Festivals large and from sources outside of Travel Manitoba. Travel small can’t wait to welcome you back to dance to the music, eat tasty treats and Manitoba provides this publication as a public service and individuals should confirm any information with immerse yourself into local culture. We have not included any festivals or events the individual operator before acting on it. Travel in this guide, but check with your favourites to find out how to you can celebrate Manitoba, its directors and employees: with them this year. For the most up-to-date information on festivals and events 1. are not liable for damages, injury, losses or costs of happening in Manitoba, go to travelmanitoba.com/events. any kind, arising from the use of or reliance on any information in this publication; 2. make no representation, warranty or assurance, express or implied, in relation to the accuracy or Manitoba encompasses Treaty 1, 2, 3, 4 and 5 Territory and communities who are signatories to Treaties 6 currency of the information in this publication; and and 10. It is the original lands of the Anishinaabeg, Anish-Ininiwak, Dakota, Dene, Ininiwak and Nehethowuk 3.