22/Apr 02-1/88/04/14 Address by Prime Minister Mr Lee Kuan

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The King's Nation: a Study of the Emergence and Development of Nation and Nationalism in Thailand

THE KING’S NATION: A STUDY OF THE EMERGENCE AND DEVELOPMENT OF NATION AND NATIONALISM IN THAILAND Andreas Sturm Presented for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy of the University of London (London School of Economics and Political Science) 2006 UMI Number: U215429 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Dissertation Publishing UMI U215429 Published by ProQuest LLC 2014. Copyright in the Dissertation held by the Author. Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. ProQuest LLC 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 I Declaration I hereby declare that the thesis, submitted in partial fulfillment o f the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy and entitled ‘The King’s Nation: A Study of the Emergence and Development of Nation and Nationalism in Thailand’, represents my own work and has not been previously submitted to this or any other institution for any degree, diploma or other qualification. Andreas Sturm 2 VV Abstract This thesis presents an overview over the history of the concepts ofnation and nationalism in Thailand. Based on the ethno-symbolist approach to the study of nationalism, this thesis proposes to see the Thai nation as a result of a long process, reflecting the three-phases-model (ethnie , pre-modem and modem nation) for the potential development of a nation as outlined by Anthony Smith. -

Download This Case As A

CSJ‐ 08 ‐ 0006.0 Settle or fight? Far Eastern Economic Review and Singapore In the summer of 2006, Hugo Restall—editor-in-chief of the monthly Far Eastern Economic Review (FEER)--published an article about a marginalized member of the political opposition in Singapore. The piece asserted that the Singapore government had a remarkable record of winning libel suits, which suggested a deliberate effort to neutralize opponents and subdue the press. Restall hypothesized that instances of corruption were going unreported because the incentive to investigate them was outweighed by the threat of an unwinnable libel suit. Singapore’s ruling family reacted swiftly. Lawyers for Prime Minister Lee Hsien Loong and his father Lee Kuan Yew, the founder of modern Singapore, asserted that the article amounted to an accusation against their clients of personal incompetence and corruption. In a series of letters, the Lees’ counsel demanded a printed apology, removal of the offending article from FEER’s website, and compensation for damages. The magazine maintained that Restall’s piece was not libelous; nonetheless, it offered to take mitigating action short of the three demands. But the Lees remained adamant. Then, in a move whose timing defied coincidence, the government Ministry of Information, Communications and the Arts informed FEER that henceforth it would be subject to new, and onerous, regulations. These actions were not without precedent. Singapore was an authoritarian, if prosperous, country. The Lee family--which claimed that the country’s ruling precepts were rooted in Confucianism, a philosophy that vested power in an enlightened ruler—tolerated no criticism. The Lees had been in charge for decades. -

Reporting Asia the Asian 'Way' - Issues and Constraints

Asia Pacific Media ducatE or Issue 9 Article 13 7-2000 Reporting Asia the Asian 'way' - issues and constraints K. Seneviratne Ngee Ann Polytechnic, Singapore Follow this and additional works at: https://ro.uow.edu.au/apme Recommended Citation Seneviratne, K., Reporting Asia the Asian 'way' - issues and constraints, Asia Pacific Media Educator, 9, 2000, 170-180. Available at:https://ro.uow.edu.au/apme/vol1/iss9/13 Research Online is the open access institutional repository for the University of Wollongong. For further information contact the UOW Library: [email protected] KALINGA SENEVIRATNE: Reporting Asia ... Reporting Asia The Asian ‘Way’ - Issues And Constraints There is a growing debate in South East Asia regarding Asian perspectives in news reporting. This has been triggered by the aftermath of the Asian financial crisis. Commentators and politicians in the region have claimed that Western media reporting has played a role in undermining their economies. There is a strong feeling that their negative reporting of the region impacted on the loss of investor confidence There are also counter moves to establish an ‘Asian Media’, where the voices of the Asian people will be heard much louder and clearer. This paper attempts to look at some of the issues underlining these moves and how such an indigenous media could develop and what bottlenecks may lie ahead. Kalinga Seneviratne Ngee Ann Polytechnic, Singapore “Objectivity is a sense of no view, I don’t think that is possible. I think a completely objective story or a completely objective publication will be a boring one to read. -

SOPA 2013 Awards Brochure

About the SOPA Awards for Editorial Excellence The SOPA Awards for Editorial Excellence were established in 1999 as a tribute to editorial excellence in both traditional and new media, and were designed to encourage editorial vitality throughout the region. The awards cover a broad range of categories reflecting Asia’s diverse geo-political environment and vibrant editorial scene. Central to the SOPA Awards’ ongoing success is the high caliber of international judges who preside over the award entries. The SOPA Awards have consistently secured judges from many of the region’s leading newspapers as well as consumer and trade magazines and academics from prestigious universities – a reflection of the stature of the awards. Judges ensure that entries are analyzed and selected according to a demanding set of criteria. The SOPA Awards are coordinated by a committee of publishing professionals from the business and editorial sectors. These dedicated individuals volunteer their time throughout the year to ensure the awards’ rules, judges, entries, event, sponsorships and promotions all come together smoothly. The SOPA Awards set a valuable benchmark for the industry, and have become news items in their own right, generating media coverage and attention not only across the Asia-Pacific region, but also on the global arena. Corporate Support Sponsorship is always essential to maintain the sustainability and the growth of the Awards. SOPA is grateful for receiving generous support from different sectors in the society. The SOPA 2013 Awards for Editorial Excellence is supported by Invest Hong Kong - Gold Sponsor, and Hong Kong High Technology Limited as the Silver Sponsor. -

Download/File Ce8c32197b28a5d438136a3bd8252b7c.Pdf> (Accessed 17 April 2018)

Bibliography ABC News. “Car Bomb Attack outside Busy Pattani Supermarket in Thailand Injures at Least 60”. 10 May 2017 <http://www.abc.net.au/news/2017-05-10/ car-bomb-attack-outside-thailand-supermarket-injures-60/8512732> (accessed 6 December 2017). Abdul Hadi Awang. “PAS Condemns Bombing of Supermarket in Southern Thailand”. Buletin Online, 12 May 2017 <http://buletinonline.net/v7/index. php/pas-condemns-bombing-supermarket-southern-thailand/> (accessed 6 December 2017). Abu Hafez Al-Hakim (pseud.). “The Peace Talk Resumes?” Deep South Watch, 4 December 2014 <https://www.deepsouthwatch.org/node/6485> (accessed 6 December 2017). ———. “What is MARA Patani?” Deep South Watch, 26 May 2015 <https://www. deepsouthwatch.org/en/node/7211> (accessed 6 December 2017). ———. “Dissecting the T-O-R”. Deep South Watch, 19 May 2016 <https://www. deepsouthwatch.org/node/8733> (accessed 6 December 2017). Aim Sinpeng. “Party-Movement Coalition in Thailand’s Political Conflict (2005– 2011)”. In Contemporary Socio-Cultural and Political Perspectives on Thailand, edited by Pranee Liamputtong, pp. 157–68. Dordrecht: Springer, 2013a. ———. “State Repression in Cyberspace: The Case of Thailand”. Asian Politics & Policy 5, no. 3 (July 2013b): 421–40. ———. “The Power of Political Movement and the Collapse of Democracy in Thailand”. Doctoral dissertation, University of British Columbia, 2013c. Akhom Detthongkhum. Hua chueak wua chon [The knot of the fighting bull]. Bangkok: Thailand Research Fund, 2000. Akin Rabibhadana. “The Organization of Thai Society in the Early Bangkok Period, 1728–1873”. Southeast Asia Program Data Paper Series, no. 74. Ithaca: Southeast Asia Program, Cornell University, 1969. Al Jazeera America. “Thai Opposition to Boycott 2014 Election”. -

Historical Legacies and Problems of Democratization in Thailand

Successful Transition, Failed Consolidation: Historical legacies and Problems of Democratization in Thailand Inaugural-Dissertation zur Erlangung der Doktorwürde der Philosophischen Fakultät der Albert-Ludwigs-Universität Freiburg i. Br. vorgelegt von Chaiwatt Mansrisuk aus Bangkok, Thailand SS 2017 Erstgutachter: Prof. Dr. Jürgen Rüland Zweitgutachter: Prof. Dr. Andreas Mehler Vorsitzender des Promotionsausschusses Der Gemeinsamen Kommission der Philologischen, Philosophischen und Wirtschafts- und Verhaltenswissenschaftlichen Fakultät: Prof. Dr. Joachim Grage Datum der Fachprüfung im Promotionsfach: 11.07.2017 Acknowledgements This dissertation which was a product of my long and complicated journey would not be complete without the generosity of and support from numerous people and institutions. First and foremost, I am indebted to Thailand's Commission on Higher Education for granting me a scholarship to pursue my study in Germany between 2009 and 2013. I also would like to thank the German Academic Exchange Service (DAAD) for financially supporting me to attend German language courses at Goethe Institutes in Bangkok and Mannheim before enrolling in a doctoral study at the University of Freiburg. At the University of Freiburg, I would like to express my deepest gratitude to my supervisor, Professor Dr. Jürgen Rüland. I am extremely grateful for the time and effort he has dedicated to inspiringly and patiently supervising my dissertation, and kindly providing me assistance whenever I needed it. I also wish to thank Paruedee Nguitragool for her kind assistance throughout the period of my stay in Freiburg. I am fortunate to pursue my doctoral study at the Political Science Department and the Southeast Asia Program where I was privileged from support, fascinating ideas and friendship. -

繆炎璋 Ng Kai Chung 伍啓忠

DO MERGERS NECESSARILY CREATE VALUE FOR SHAREHOLDERS? A CASE STUDY OF THE MEGA-MERGER OF PACIFIC CENTURY CYBERWORKS AND CABLE & WIRELESS HKT by MAO YIM CHEUNG 繆炎璋 NG KAI CHUNG 伍啓忠 MBA PROJECT REPORT Presented to The Graduate School In Partial Fulfilment of the Requirements for the Degree of MASTER OF BUSINESS ADMINISTRATION TWO-YEAR MBA PROGRAMME THE CHINESE UNIVERSITY OF HONG KONG May 2001 The Chinese University of Hong Kong holds the copyright of this project. Any person(s) intending to use a part or whole of the materials in the project in a proposed publication must seek copyright relaease from the Dean of the Graduate School. jhf 统系馆 iQur^i) ~~university i^j NS^BRARY SYSTFMyW APPROVAL Name: Mao Yim-Cheung (John) Ng Kai-Chung (Cyrus) Degree: Master of Business Administration Title of Project: Do Mergers Necessarily Create Value for Shareholders? A Case Study of the Mega-Merger of Pacific Century Cyber Works and Cable & Wireless HKT Name of Supervisor: 刚( Signature of Supervisor: Date Approved: 丨: f�\ i ABSTRACT When the dust settles on 2000 and the financial markets look back over the year, one company will be seen to have dominated the headlines: Pacific Century CyberWorks (PCCW). The corporation outmaneuvered state-controlled Singapore Telecom and media magnate Rupert Murdoch in a brief but epic battle to acquire Cable & Wireless HKT (HKT). Through bank loans and share placement, Richard Li Tzar-kai (the second son of Hong Kong Tycoon Li Ka-shing) finally succeeded in mustering as much as $38.1 billion in a buyout of Hong Kong's oldest telecommunications company (among the HSI-constituent blue chips). -

Restraining Arbitrary Power in Thailand: the Sociological Approach in Examining the Rule of Law

RESTRAINING ARBITRARY POWER IN THAILAND: THE SOCIOLOGICAL APPROACH IN EXAMINING THE RULE OF LAW PORNSAKOL PANIKABUTARA COOREY A THESIS SUBMITTED IN FULFILMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF JURIDICAL SCIENCE FACULTY OF LAW UNIVERSITY OF NEW SOUTH WALES APRIL 2010 PLEASE TYPE THE UNIVERSITY OF NEW SOUTH WALES Thesis/Dissertation Sheet Surname or Family name: COOREY First name: PORNSAKOL Other name/s: PANIKABUTARA Abbreviation for degree as given in the University calendar: SJD School: LAW Faculty: LAW Title: Restraining arbitrary power in Thailand: The sociological approach in examining the rule of law Abstract 350 words maximum: (PLEASE TYPE) The primary objective of this thesis is to develop and use a new framework to examine the existence of the rule of law in Thailand. Many writers believe that Thailand is a nation which lacks sufficient constraint on the exercise of arbitrary power. These writers often blame the judiciary and other key institutions for not curbing corruption and other forms of abuses of power. While each writer adopts a different approach in analysing the rule of law, their views are almost always taken out of context and do not tell the entire story. This is considered as inadequate, as these views often fail to appreciate the core sociological aspects of the rule of law. It is these core sociological aspects which are considered as essential to understanding the way the rule of law operates in Thailand. Without a proper understanding of the traditions and culture of Thailand, it is misguiding to simply transplant the classic view of the rule of law and compare its key institutions in an ad hoc way. -

Control of Advertisements and Sale of Tobacco (Foreign Newspapers)

Front Page SMOKING (CONTROL OF ADVERTISEMENTS AND SALE OF TOBACCO) ACT (CHAPTER 309, SECTION 7 (1)) SMOKING (CONTROL OF ADVERTISEMENTS AND SALE OF TOBACCO) (FOREIGN NEWSPAPERS) (CONSOLIDATION) NOTIFICATION History G.N. NO. S -> 1994 -> 2000REVISED 193/93 REVISEDEDITION EDITION N 3 N 2 Arrangement of Provisions 1 2 THE SCHEDULE Actual Provisions SMOKING (CONTROL OF ADVERTISEMENTS AND SALE OF TOBACCO) ACT (CHAPTER 309, SECTION 7 (1)) SMOKING (CONTROL OF ADVERTISEMENTS AND SALE OF TOBACCO) (FOREIGN NEWSPAPERS) (CONSOLIDATION) NOTIFICATION 1. This Notification may be cited as the Smoking (Control of Advertisements and Sale of Tobacco) (Foreign Newspapers) (Consolidation) Notification. 2. Part II of the Act shall apply to any advertisement relating to smoking contained in a newspaper specified in the Schedule which is printed or published outside Singapore and is brought into Singapore for sale, free distribution or personal use. THE SCHEDULE Name of Newspaper Name and Address of Publisher 1. Asian Business Far East Trade Press Limited, 2/F Kai Tak Commercial Building, 317 Des Voeux Road, Central Hong Kong. 2. Newsweek Newsweek Incorporation, 47/F, Bank of China Tower, 1 Garden Road, Central Hong Kong. 3. Time Magazine Time Incorporation Magazine Company, Time & Life Building, Rockefeller Centre, New York, NY 10020, USA. 4. World Executive Digest World Executive’s Digest Incorporation, 3/F, Garden Square Building, Greenbelt Drive, Legaspi Village, Makati, Metro, Manila, Philippines. 5. Yazhou Zhoukan Asiaweek Limited, 37/F, Citicorp Centre, 18 Whitfield Road, Causeway Bay, Hong Kong. 6. Asiaweek Asiaweek Limited, 37/F, Citicorp Centre, 18 Whitfield Road, Causeway Bay, Hong Kong. 7. Infant Times Infant Times Association, 28 Blackwood Drive, Mount Nasura, Armadale, Perth, Western Australia 6112. -

The Role of the Nation-State: Evolution of STAR TV in China and India By

The role of the nation-state: Evolution of STAR TV in China and India By Yu-li Chang Assistant Professor Department of Communication Northern Illinois University E-mail: [email protected] Tel: (815)753-1711 Copyright © 2006 by Yu-li Chang Paper Submitted to the 6th Annual Global Fusion Conference Chicago, 2006 Abstract The purpose of this study is to examine the role of the nation-state by analyzing the evolution of STAR TV’s in India and China. STAR TV, the first pan-Asian satellite television, represents the global force; while the governments in India and China represent the local forces faced with challenges brought about by globalization. This study found that the nation-states in China and India still were forces that had to be dealt with. In China, the state continued to exercise tight control over foreign broadcasters in almost every aspect – be it content or distribution. In India, the global force seemed to have greater leverage in counteracting the state, but only in areas where the state was willing to compromise, such as allowing entertainment channels to be fully owned by foreign broadcasters. In areas where the government thought needed protection to ensure national security and identity, the state still exercised autonomy to formulate and implement policies restricting the global force. Author Bio The author earned her Ph.D. from the E.W. Scripps School of Journalism at Ohio University in 2000 and is now an assistant professor in the department of communication at Northern Illinois University. Her major research interest focuses on globalization of mass media, especially programming strategies of transnational satellite broadcasters in Asia and the implications of their programming strategies on theory building in the research field of globalization. -

Duncan Mccargo and Ukrist Pathmanand

Mc A fascinating insight into Thai politics in the lead-up to the Thaksin revolution c Since 1932, Thai politics has undergone numerous political ‘reforms’, often accompanied by constitutional revisions and shifts in the argo location of power. Following the events of May 1992, there were strong pressures from certain groups in Thai society for a fundamental overhaul of the political order, culminating in the drafting and promulgation of a new constitution in 1997. However, constitutional reform is only one small part of a wide r range of possible reforms, including that of the electoral system, education, the bureaucracy, health and welfare, the media – and even the military. Indeed, the economic crisis which engulfed efor Thailand in 1997 led to a widespread questioning of the country’s social and political structures. With the sudden end of rapid economic growth, the urgency of reform and adaptation to Thailand’s changing circumstances became vastly more acute. It was against M this background that the Thai parliament passed major changes to ing the electoral system in late 2000, just weeks before the January 2001 election. Reflecting on the twists and turns of reform in Thailand over the edited by years and with the first in-depth scholarly analysis of how successful Thai were the recent electoral reforms, this volume is a ‘must have’ for everyone interested in Thai politics and its impact on the wider Asian Duncan Mccargo political scene. “[a] timely book on the “new” Thai politics which certainly contributes a Poli great deal to -

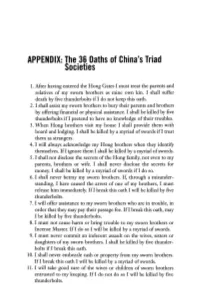

APPENDIX: the 36 Oaths of China's Triad Societies

APPENDIX: The 36 Oaths of China's Triad Societies 1. Mter having entered the Hong Gates I must treat the parents and relatives of my sworn brothers as mine own kin. I shall suffer death by five thunderbolts if I do not keep this oath. 2. I shall assist my sworn brothers to bury their parents and brothers by offering financial or physical assistance. I shall be killed by five thunderbolts if I pretend to have no knowledge of their troubles. 3. When Hong brothers visit my house I shall provide them with board and lodging. I shall be killed by a myriad of swords if I treat them as strangers. 4. I will always acknowledge my Hong brothers when they identify themselves. If I ignore them I shall be killed by a myriad of swords. 5. I shall not disclose the secrets of the Hong family, not even to my parents, brothers or wife. I shall never disclose the secrets for money. I shall be killed by a myriad of swords if I do so. 6. I shall never betray my sworn brothers. If, through a misunder standing, I have caused the arrest of one of my brothers, I must release him immediately. If I break this oath I will be killed by five thunderbolts. 7. I will offer assistance to my sworn brothers who are in trouble, in order that they may pay their passage fee. If I break this oath, may I be killed by five thunderbolts. 8. I must not cause harm or bring trouble to my sworn brothers or Incense Master.