The Biology and Conservation of the Blue Crab, Callinectes Sapidus Rathbun By

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

National Monitoring Program for Biodiversity and Non-Indigenous Species in Egypt

UNITED NATIONS ENVIRONMENT PROGRAM MEDITERRANEAN ACTION PLAN REGIONAL ACTIVITY CENTRE FOR SPECIALLY PROTECTED AREAS National monitoring program for biodiversity and non-indigenous species in Egypt PROF. MOUSTAFA M. FOUDA April 2017 1 Study required and financed by: Regional Activity Centre for Specially Protected Areas Boulevard du Leader Yasser Arafat BP 337 1080 Tunis Cedex – Tunisie Responsible of the study: Mehdi Aissi, EcApMEDII Programme officer In charge of the study: Prof. Moustafa M. Fouda Mr. Mohamed Said Abdelwarith Mr. Mahmoud Fawzy Kamel Ministry of Environment, Egyptian Environmental Affairs Agency (EEAA) With the participation of: Name, qualification and original institution of all the participants in the study (field mission or participation of national institutions) 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS page Acknowledgements 4 Preamble 5 Chapter 1: Introduction 9 Chapter 2: Institutional and regulatory aspects 40 Chapter 3: Scientific Aspects 49 Chapter 4: Development of monitoring program 59 Chapter 5: Existing Monitoring Program in Egypt 91 1. Monitoring program for habitat mapping 103 2. Marine MAMMALS monitoring program 109 3. Marine Turtles Monitoring Program 115 4. Monitoring Program for Seabirds 118 5. Non-Indigenous Species Monitoring Program 123 Chapter 6: Implementation / Operational Plan 131 Selected References 133 Annexes 143 3 AKNOWLEGEMENTS We would like to thank RAC/ SPA and EU for providing financial and technical assistances to prepare this monitoring programme. The preparation of this programme was the result of several contacts and interviews with many stakeholders from Government, research institutions, NGOs and fishermen. The author would like to express thanks to all for their support. In addition; we would like to acknowledge all participants who attended the workshop and represented the following institutions: 1. -

A New Record of Callinectes Sapidus Rathbun, 1896 (Crustacea: Decapoda: Brachyura) from the Cantabrian Sea, Bay of Biscay, Spain

Aquatic Invasions (2006) Volume 1, Issue 3: 186-187 DOI 10.3391/ai.2006.1.3.14 © 2006 The Author(s) Journal compilation © 2006 REABIC (http://www.reabic.net) This is an Open Access article Short communication A new record of Callinectes sapidus Rathbun, 1896 (Crustacea: Decapoda: Brachyura) from the Cantabrian Sea, Bay of Biscay, Spain Jesús Cabal1*, Jose Antonio Pis Millán2 and Juan Carlos Arronte3 1Instituto Español de Oceanografía, Centro Oceanográfico de Gijón, Avenida Príncipe de Asturias 70, Bis. 33212, Gijón, Spain, E-mail: [email protected] 2Centro de Experimentación Pesquera, Avenida Príncipe de Asturias, s/n. 33212 Gijón, Spain, E-mail: [email protected] 3Departamento de Biología de Organismos y Sistemas (Zoología), Universidad de Oviedo, Calle Catedrático Rodrigo Uria, s/n. 33071 Oviedo, Spain, E-mail: [email protected] *Corresponding author Received 19 June 2006; accepted in revised form 24 July 2006 Abstract A single immature female specimen of the blue crab, Callinectes sapidus Rathbun, 1896 was collected on 22 September 2004 in a refrigeration pipe of the power station at Port of El Musel, Gijón, Northern Spain. This is the first record of this alien species from northern Spain. Key words: Callinectes sapidus, alien species, blue crab, Biscay Bay, Spain A single immature female specimen of the estua- immature as the size for mature females is rine blue crab, Callinectes sapidus Rathburn, between 120-170 mm, as indicated in studies of 1896 (Figure 1) was collected on 22 September the Chesapeake Bay (Cadman and Weinstein 2004 from the grille of the refrigeration pipe in a 1985). -

The First Recorded Occurrences of the Invasive Crab Callinectes Sapidus Rathbun, 1896 (Crustacea: Decapoda: Portunidae) in Coast

BioInvasions Records (2018) Volume 7, Issue 2: 191–196 Open Access DOI: https://doi.org/10.3391/bir.2018.7.2.12 © 2018 The Author(s). Journal compilation © 2018 REABIC Rapid Communication The first recorded occurrences of the invasive crab Callinectes sapidus Rathbun, 1896 (Crustacea: Decapoda: Portunidae) in coastal lagoons of the Balearic Islands (Spain) Lluc Garcia1, Samuel Pinya1,2,*, Victor Colomar3, Tomàs París3, Miquel Puig3, Maties Rebassa4 and Joan Mayol4 1Museu Balear de Ciències Naturals, Carretera Palma-Port de Sóller, km 30. P.O. Box 55. Sóller 07100, Balearic Islands, Spain 2Interdisciplinary Ecology Group, University of the Balearic Islands, Ctra. Valldemossa km 7,5, 07122 Palma, Balearic Islands, Spain 3Consorci per a la Recuperació de Fauna de les Illes Balears (COFIB), Ctra Sineu km 15.400, Santa Eugènia 07142, Balearic Islands, Spain 4Direcció General d’Espais Naturals i Biodiversitat, Conselleria de Medi Ambient Agricultura i Pesca, Gremi de Corredors, 10, Polígon Son Rossinyol, Palma 07009, Balearic Islands, Spain *Corresponding author E-mail: [email protected] Received: 26 September 2017 / Accepted: 31 January 2018 / Published online: 5 February 2018 Handling editor: Thomas Therriault Abstract The introduction of species is a major threat to biodiversity conservation. Island biodiversity is especially sensitive to the arrival of new species, and species introductions are one of the major concerns of conservation management policies. Here, we report for the first time the arrival of Callinectes sapidus, a new potentially invasive crab species from the East coast of America to the Balearic Islands (Spain). It appeared simultaneously in both Mallorca and Menorca islands. Nine different records of 20 individuals were documented in six different localities, suggesting an initial colonization process of the territory. -

Physiological and Biochemical Responses to Hypoxia in the Blue Crab, Callinectes Sapidus Rathbun, the Lesser Blue Crab, Callinec

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses Graduate School 1993 Physiological and Biochemical Responses to Hypoxia in the Blue Crab, Callinectes Sapidus Rathbun, the Lesser Blue Crab, Callinectes Similis Williams, and the Southern Oyster Drill, Stramonita Haemastoma Linnaeus. Tapash Das Louisiana State University and Agricultural & Mechanical College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses Recommended Citation Das, Tapash, "Physiological and Biochemical Responses to Hypoxia in the Blue Crab, Callinectes Sapidus Rathbun, the Lesser Blue Crab, Callinectes Similis Williams, and the Southern Oyster Drill, Stramonita Haemastoma Linnaeus." (1993). LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses. 5625. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses/5625 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses by an authorized administrator of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. -

THE SWIMMING CRABS of the GENUS CALLINECTES (DECAPODA: PORTUNIDAE) L! •• ' ' ' •'

A-G>. \KJ>\\if THE SWIMMING CRABS OF THE GENUS CALLINECTES (DECAPODA: PORTUNIDAE) l! •• ' ' ' •' AUSTIN B. WILLIAMS1 F: * * ABSTRACT The genus Callinectes and its 14 species are reevaluated. Keys to identification, descriptions of species, ranges of variation for selected characters, larval distribution, and the fossil record as well as problems in identification are discussed. Confined almost exclusively to shallow coastal waters, the genus has apparently radiated both northward and southward from a center in the Atlantic Neotropical coastal region as well as into the eastern tropical Pacific through continuous connections prior to elevation of the Panamanian isthmus in the Pliocene epoch and along tropical West Africa. Eleven species occur in the Atlantic, three in the Pacific. Callinectes marginatus spans the eastern and western tropical Atlantic. Callinectes sapidus, with the broadest latitudinal distribution among all the species (Nova Scotia to Argentina), has also been introduced in Europe. All species show close similarity and great individual variation. Both migration and genetic continuity appear to be assisted by transport of larvae in currents. Distributional patterns parallel those of many organisms, especially members of the decapod crustacean genus Penaeus which occupy similar habitats. The blue crab, Callinectes sapidus Rathbun, a sta- we have in England." A similar record is ple commodity in fisheries of eastern and southern Marcgrave's account in 1648 (Lemos de Castro, United States, is almost a commonplace object of 1962) of a South American Callinectes [= danae fisheries and marine biological research, but its Smith (1869)], one of the common portunids used taxonomic status has been questionable for a long for food. -

Callinectes Sapidus) Dredged from Chesapeake Bay

Diseases, Parasites, and Symbionts of Blue Crabs (Callinectes sapidus) Dredged from Chesapeake Bay Gretchen A. Messick Journal of Crustacean Biology, Vol. 18, No. 3. (Aug., 1998), pp. 533-548. Stable URL: http://links.jstor.org/sici?sici=0278-0372%28199808%2918%3A3%3C533%3ADPASOB%3E2.0.CO%3B2-I Journal of Crustacean Biology is currently published by The Crustacean Society. Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use, available at http://www.jstor.org/about/terms.html. JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use provides, in part, that unless you have obtained prior permission, you may not download an entire issue of a journal or multiple copies of articles, and you may use content in the JSTOR archive only for your personal, non-commercial use. Please contact the publisher regarding any further use of this work. Publisher contact information may be obtained at http://www.jstor.org/journals/crustsoc.html. Each copy of any part of a JSTOR transmission must contain the same copyright notice that appears on the screen or printed page of such transmission. The JSTOR Archive is a trusted digital repository providing for long-term preservation and access to leading academic journals and scholarly literature from around the world. The Archive is supported by libraries, scholarly societies, publishers, and foundations. It is an initiative of JSTOR, a not-for-profit organization with a mission to help the scholarly community take advantage of advances in technology. For more information regarding JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. http://www.jstor.org Tue Dec 4 16:44:38 2007 JOURNAL OF CRUSTACEAN BIOLOGY, 18(3): 533-548, 1998 DISEASES, PARASITES, AND SYMBIONTS OF BLUE CRABS (CALLINECTES SAPIDUS) DREDGED FROM CHESAPEAKE BAY Gretchen A. -

Composition Systematics in the Exoskeleton of the American Lobster, Homarus Americanus and Implications for Malacostraca

feart-07-00069 April 3, 2019 Time: 21:28 # 1 ORIGINAL RESEARCH published: 05 April 2019 doi: 10.3389/feart.2019.00069 Composition Systematics in the Exoskeleton of the American Lobster, Homarus americanus and Implications for Malacostraca Sebastian T. Mergelsberg*, Robert N. Ulrich, Shuhai Xiao and Patricia M. Dove Department of Geosciences, Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University, Blacksburg, VA, United States Studies of biominerals from the exoskeletons of lobsters and other crustaceans report chemical heterogeneities across disparate body parts that have prevented the development of composition-based environmental proxy models. Anecdotal evidence, however, suggests underlying composition systematics may exist in the mineral component of this biocomposite material. We test this idea by designing a protocol Edited by: to separately extract the mineral [amorphous calcium carbonate (ACC) plus calcite] and Aleksey Sadekov, The University of Western Australia, organic (chitin plus protein) fractions of the exoskeleton. The fractions were analyzed Australia by ICP-OES and other wet chemistry methods to quantify Mg, Ca, and P contents of Reviewed by: the bulk, mineral, and organic matrix. Applying this approach to the exoskeleton for Bronwen Cribb, The University of Queensland, seven body parts of the American lobster, Homarus americanus, we characterize the Australia chemical composition of each fraction. The measurements confirm that Mg, P, and Ca Shmuel Bentov, concentrations in lobster exoskeletons are highly variable. However, the ratios of Mg/Ca Ben-Gurion University of the Negev, Israel and P/Ca in the mineral fraction are constant for all parts, except the chelae (claws), *Correspondence: which are offset to higher values. By normalizing concentrations to obtain P/Ca and Sebastian T. -

The Arrival of the American Blue Crab, Callinectes Sapidus Rathbun, 1896 (Decapoda: Brachyura: Portunidae), in the Gulf of Lions (Mediterranean Sea)

BioInvasions Records (2019) Volume 8, Issue 4: 876–881 CORRECTED PROOF Rapid Communication The arrival of the American blue crab, Callinectes sapidus Rathbun, 1896 (Decapoda: Brachyura: Portunidae), in the Gulf of Lions (Mediterranean Sea) Céline Labrune1,*, Elsa Amilhat2,3, Jean-Michel Amouroux1, Coraline Jabouin4, Alexandra Gigou4 and Pierre Noël5 1Sorbonne Universités, CNRS, Laboratoire d’Ecogéochimie des Environnements Benthiques, LECOB UMR8222, F-66650 Banyuls-sur-Mer, France 2Univ. Perpignan Via Domitia, Centre de Formation et de Recherche sur les Environnements Méditerranéens, UMR 5110, F 66860, Perpignan, France 3CNRS, Centre de Formation et de Recherche sur les Environnements Méditerranéens, UMR 5110, F 66860, Perpignan, France 4Parc naturel marin du golfe du Lion - Agence française pour la biodiversité “Le Nadar”, Hall C - 5 square Félix Nadar - 94300 Vincennes, France 5UMS 2006 AFB-CNRS-MNHN, “Patrimoine Naturel”, Muséum national d’Histoire naturelle, CP 48, F-75231 Paris cedex 05, France Author e-mails: [email protected] (CL), [email protected] (EA), [email protected] (JMA), [email protected] (CJ), [email protected] (AG), [email protected] (PN) *Corresponding author Citation: Labrune C, Amilhat E, Amouroux J-M, Jabouin C, Gigou A, Noël Abstract P (2019) The arrival of the American blue crab, Callinectes sapidus Rathbun, 1896 After reaching the Italian and Spanish coasts of the Western Mediterranean Sea, the (Decapoda: Brachyura: Portunidae), in the American blue crab Callinectes sapidus was finally observed on the French coasts. Gulf of Lions (Mediterranean Sea). To date, it has been caught in eleven lagoons and three sites of the French coast. -

Factors Affecting the Distribution and Abundance of the Blue Crab in Chesapeake Bay

W&M ScholarWorks VIMS Books and Book Chapters Virginia Institute of Marine Science 1987 Factors Affecting The Distribution And Abundance Of The Blue Crab In Chesapeake Bay W. A. Van Engel Virginia Institute of Marine Science Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wm.edu/vimsbooks Part of the Environmental Indicators and Impact Assessment Commons, and the Natural Resources and Conservation Commons Recommended Citation Van Engel, W. A., "Factors Affecting The Distribution And Abundance Of The Blue Crab In Chesapeake Bay" (1987). VIMS Books and Book Chapters. 94. https://scholarworks.wm.edu/vimsbooks/94 This Book Chapter is brought to you for free and open access by the Virginia Institute of Marine Science at W&M ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in VIMS Books and Book Chapters by an authorized administrator of W&M ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. CONTAIMJDINIAINJT PROBLEMS AINID MANAGEMIEINJT OF LOVING CIHIESAIPEAKE BAY RESOURCES EDITED BY SHYAMAL K. MAJUMDAR, Ph.D. Professor of Biology Lafayette College Easton, Pennsylvania 18042 LENWOOD W. HALL, Jr., M.S. Senior Staff Biologist The Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory Aquatic Ecology Section Shady Side, Maryland 20764 HERBERT M. AUSTIN, Ph.D. Professor of Marine Science The College of William and Mary Virginia Institute of Marine Science Gloucester Point, Virginia 23062 ~ ~ ---...;:....._~, LIBRARY "~~ ( of the i\ RGINIA INSTITUTE ; of 1/ MARINE SCIENCE ~ '/ .........._=-i__._.._-c:- ? Founded on April 18, 1924 A Publication of The Pennsylvania Academy of Science Contaminant Problems and Management of Living Chesapeake Bay Resources. Edited by S. K. Majumdar, L. -

New Mediterranean Biodiversity Records (July 2016) T

Collective Article Mediterranean Marine Science Indexed in WoS (Web of Science, ISI Thomson) and SCOPUS The journal is available on line at http://www.medit-mar-sc.net DOI: 10.12681/mms.1734 New Mediterranean Biodiversity Records (July 2016) T. DAILIANIS1,2, O. AKYOL3, N. BABALI4, M. BARICHE5, F. CROCETTA6, V. GEROVASILEIOU1,2, R. GHANEM7,8, M. GÖKOĞLU9, T. HASIOTIS2, A. IZQUIERDO-MUÑOZ10, D. JULIAN9, S. KATSANEVAKIS2, L. LIPEJ11, E. MANCINI12 , CH. MYTILINEOU6, K. OUNIFI BEN AMOR7,8, A. ÖZGÜL3, M. RAGKOUSIS2, E. RUBIO-PORTILLO13 , G. SERVELLO14 , M. SINI2, C. STAMOULI6, A. STERIOTI1, S. TEKER9, F. TIRALONGO12 and D. TRKOV11 1 Hellenic Centre for Marine Research, Institute of Marine Biology, Biotechnology, and Aquaculture, 71500 Heraklion Crete, Greece 2 University of the Aegean, Department of Marine Sciences, University Hill, 81100 Mytilene, Greece 3 Ege University, Faculty of Fisheries, 35440, Urla, Izmir, Turkey 4 National Research Center for the Developing of Fisheries and Aquaculture (CNRDPA), Algeria 5 American University of Beirut, Department of Biology, PO Box 11-0236, Beirut 1107 2020, Lebanon 6 Hellenic Centre for Marine Research, Institute of Marine Biological Resources and Inland Waters, 19013 Anavyssos, Greece 7 Département des Ressources Animales, Halieutiques et des Technologies Agroalimentaires, Institut National Agronomique de Tunisie, Université de Carthage, Tunis, Tunisia 8 Laboratoire de Biodiversité, Biotechnologies et Changements climatiques, Faculté des Sciences de Tunis, Université Tunis El Manar, Tunis, Tunisia -

Atlantic Blue Crab Callinectes Sapidus

Supplemental Volume: Species of Conservation Concern SC SWAP 2015 Atlantic Blue Crab Callinectes sapidus Contributor (2013): Larry DeLancey (SCDNR) DESCRIPTION Taxonomy and Basic Description The Atlantic blue crab is a member of the family Portunidae, the swimming crabs, whose final segment (dactyl) of the fifth walking leg is flattened to a paddle-like appearance to enhance swimming ability. The family is of global economic importance, supporting large fisheries in the Americas and Asia. The Atlantic blue crab can be distinguished from the closely related lesser blue crab, Callinectes similis, by its larger adult size (>13 cm carapace width), red color on the chelipeds (claws), and the presence of two interorbital teeth of the frontal margin of the carapace compared to the two interorbital teeth present in C. sapidus. Callinectes sapidus also displays a more bluish-green color on the carapace, whereas C. similis is characterized by a more violet hue on the carapace and legs (Williams 1984). Spawning in C. sapidus occurs after the female undergoes a terminal molt and is impregnated by the male crab while she is in a “soft” state, prior to the exoskeleton hardening (Van Engel 1958). The females will carry the sperm internally until they deposit eggs that attach to setae on specialized pleopods, forming an egg mass (sponge). Several sponges can be produced from a single mating event (Hines et al. 2003). Figure 1 represents the cycle that follows. Mature females migrate close to or into the ocean prior to eggs hatching; in South Carolina, this occurs from March through early fall (Eldridge and Waltz 1977). -

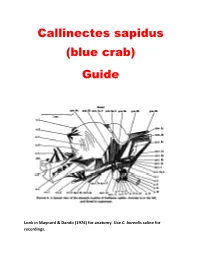

Callinectes Sapidus (Blue Crab) Guide

Callinectes sapidus (blue crab) Guide Look in Maynard & Dando (1974) for anatomy. Use C. borealis saline for recordings. Callinectes sapidus Intracellular Traces 004_102 LP lvn gpn vlvn PD lvn gpn vlvn Blue Crabs of the South Atlantic Bight Native and Occasional species of Callinectes (or, when isn’t a blue crab a blue crab?) Classification. Kingdom: Animalia Phylum: Arthropoda Subphylum: Crustacea Class: Malacostraca Subclass: Eumalacostraca Superorder: Eucarida Order: Decapoda Suborder: Pleocyemata Infraorder: Brachyura Superfamily: Portunoidea Family: Portunidae Genus: Callinectes Common name: Blue crab Physical characteristics: Callinectes species, like most portunids, have a pair of flat, oar shaped rear legs (pereopods) called swimmerets. Members of the genus have a flat broad carapace with a series of distinct lateral teeth along each frontal margin between the eyes and the large terminal spines at the widest part of the carapace. There are also 4-6 “frontal teeth” between the eyes; the number, shape, and relative length of these teeth are useful in distinguishing the different species. Often the crabs are olive green on the back of the carapace and white on the belly, with blue or red areas coloring parts of the forelimbs (chelipeds). Additional colors and pigment patterns can produce variations that are characteristic of different species (see below). Common local species: Callinectes sapidus, C. similis, C. ornatus (C. ornatus found mainly offshore) Occasionally occurring species: C. exasperatus, C. bocourti, C. larvatus Callinectes sapidus Callinectes sapidus, blue coloration caused by abnormal pigmentation Callinectes ornatus Callinectes ornatus, male (top) and immature female (bottom) Callinectes similis (immature) Callinectes bocourti Callinectes exasperatus Callinectes larvatus Diagnostic characteristic of species: In male crabs, the shape of the male gonopods (a pair of abdominal appendages that are modified for mating), may be viewed by lifting the abdomen from the underside of the crab.