Determination of Syncope Etiology Can Be Costly--What Is Necessary?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

ALS and Other Motor Neuron Diseases Can Represent Diagnostic Challenges

Review Article Address correspondence to Dr Ezgi Tiryaki, Hennepin ALS and Other Motor County Medical Center, Department of Neurology, 701 Park Avenue P5-200, Neuron Diseases Minneapolis, MN 55415, [email protected]. Ezgi Tiryaki, MD; Holli A. Horak, MD, FAAN Relationship Disclosure: Dr Tiryaki’s institution receives support from The ALS Association. Dr Horak’s ABSTRACT institution receives a grant from the Centers for Disease Purpose of Review: This review describes the most common motor neuron disease, Control and Prevention. ALS. It discusses the diagnosis and evaluation of ALS and the current understanding of its Unlabeled Use of pathophysiology, including new genetic underpinnings of the disease. This article also Products/Investigational covers other motor neuron diseases, reviews how to distinguish them from ALS, and Use Disclosure: Drs Tiryaki and Horak discuss discusses their pathophysiology. the unlabeled use of various Recent Findings: In this article, the spectrum of cognitive involvement in ALS, new concepts drugs for the symptomatic about protein synthesis pathology in the etiology of ALS, and new genetic associations will be management of ALS. * 2014, American Academy covered. This concept has changed over the past 3 to 4 years with the discovery of new of Neurology. genes and genetic processes that may trigger the disease. As of 2014, two-thirds of familial ALS and 10% of sporadic ALS can be explained by genetics. TAR DNA binding protein 43 kDa (TDP-43), for instance, has been shown to cause frontotemporal dementia as well as some cases of familial ALS, and is associated with frontotemporal dysfunction in ALS. Summary: The anterior horn cells control all voluntary movement: motor activity, res- piratory, speech, and swallowing functions are dependent upon signals from the anterior horn cells. -

Approach to a Patient with Hemiplegia and Monoplegia

CHAPTER Approach to a Patient with Hemiplegia and Monoplegia 27 Sudhir Kumar, Subhash Kaul INTRODUCTION 4. Injury to multiple cervical nerve roots. Monoplegia and hemiplegia are common neurological 5. Functional or psychogenic. symptoms in patients presenting to the emergency department as well as outpatient department. Insidious onset, gradually progressive monoplegia affecting lower limb can be caused by the following Monoplegia refers to weakness of one limb (either arm or conditions: leg) and hemiplegia refers to weakness of one arm and leg on the same side of body (either left or right side). 1. Tumor of the contralateral frontal lobe. There are a variety of underlying causes for monoplegia 2. Tumor of spinal cord at thoracic or lumbar level. and hemiplegia. The causes differ in different age groups. 3. Chronic infection of brain (frontal lobe) or spinal The causes also differ depending on the onset, progression cord (thoracic or lumbar level), such as tuberculous. and duration of weakness. Therefore, one needs to adopt a systematic approach during history taking and 4. Lumbosacral-plexopathy, due to diabetes mellitus. examination in order to arrive at the correct diagnosis. Insidious onset, gradually progressive monoplegia, Appropriate investigations after these would confirm the affecting upper limb, can be caused by one of the following diagnosis. conditions: The aim of this chapter is to systematically look at the 1. Tumor of the contralateral parietal lobe. differential diagnosis of monoplegia and hemiplegia and outline the approach needed to pinpoint the exact 2. Compressive lesion (tumor, large disc, etc) in underlying cause. cervical cord region. 3. Chronic infection of the brain (parietal lobe) or APPROACH TO THE DIAGNOSIS OF MONOPLEGIA spinal cord (cervical region), such as tuberculous. -

Neuromuscular Disorders Neurology in Practice: Series Editors: Robert A

Neuromuscular Disorders neurology in practice: series editors: robert a. gross, department of neurology, university of rochester medical center, rochester, ny, usa jonathan w. mink, department of neurology, university of rochester medical center,rochester, ny, usa Neuromuscular Disorders edited by Rabi N. Tawil, MD Professor of Neurology University of Rochester Medical Center Rochester, NY, USA Shannon Venance, MD, PhD, FRCPCP Associate Professor of Neurology The University of Western Ontario London, Ontario, Canada A John Wiley & Sons, Ltd., Publication This edition fi rst published 2011, ® 2011 by Blackwell Publishing Ltd Blackwell Publishing was acquired by John Wiley & Sons in February 2007. Blackwell’s publishing program has been merged with Wiley’s global Scientifi c, Technical and Medical business to form Wiley-Blackwell. Registered offi ce: John Wiley & Sons Ltd, The Atrium, Southern Gate, Chichester, West Sussex, PO19 8SQ, UK Editorial offi ces: 9600 Garsington Road, Oxford, OX4 2DQ, UK The Atrium, Southern Gate, Chichester, West Sussex, PO19 8SQ, UK 111 River Street, Hoboken, NJ 07030-5774, USA For details of our global editorial offi ces, for customer services and for information about how to apply for permission to reuse the copyright material in this book please see our website at www.wiley.com/wiley-blackwell The right of the author to be identifi ed as the author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the UK Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, except as permitted by the UK Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988, without the prior permission of the publisher. -

Is Hirayama a Gq1b Disease?

Neurological Sciences (2019) 40:1743–1747 https://doi.org/10.1007/s10072-019-03758-x LETTER TO THE EDITOR Is Hirayama a Gq1b disease? Sezin AlpaydınBaslo1 & Mücahid Erdoğan1 & Zeynep Ezgi Balçık1 & Oya Öztürk 1 & Dilek Ataklı1 Received: 13 November 2018 /Accepted: 7 February 2019 /Published online: 23 February 2019 # Fondazione Società Italiana di Neurologia 2019 Introduction knowledge, the association between HD and anti-ganglioside antibodies has not been reported before. Hirayama disease (HD) or juvenile muscular atrophy of We herein, present a young male patient who got the diag- distal upper extremity is a rare benign disease of motor nosis of HD, with unilateral complains but bilateral asymmet- neurons that commonly affects the cervical spinal seg- rical hand muscle weakness and atrophy accompanied by bi- ments. It is more prevalent in males and mostly seen in lateral electrophysiology and typical MRI findings. His serum teens and early 20s. Slowly progressive unilateral or was strongly positive (138%) for anti-GQ1b IgG antibody that asymmetrically bilateral weakness of hands and fore- is worth to be mentioned as a notable bystander. arms is typical. Sensory disturbances, autonomic and Informed consent was obtained from the patient included in upper motor neuron signs are extremely rare [1]. As the study. the synonym Bbenign focal amyotrophy^ implies, it reaches a plateauafterafewyears.Electromyographyrevealsasymmetri- cal chronic denervation in C7, C8, and T1 myotomes. Case Preservation of C6 myotomes is remarkable. Supportive MRI findings are anterior shift of posterior dura, enlargement of epi- A 17-year-old male was admitted with a 1 year’shistoryof dural space, and venous congestion under neck flexion. -

Motor Neuron Disease Motor Neuron Disease

Motor Neuron Disease Motor Neuron Disease • Incidence: 2-4 per 100 000 • Onset: usually 50-70 years • Pathology: – Degenerative condition – anterior horn cells and upper motor neurons in spinal cord, resulting in mixed upper and lower motor neuron signs • Cause unknown – 10% familial (SOD-1 mutation) – ? Related to athleticism Presentation • Several variations in onset, but progress to the same endpoint • Motor nerves only affected • May be just UMN or just LMN at onset, but other features will appear over time • Main patterns: – Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis – Bulbar presentaion – Primary lateral sclerosis (UMN onset) – Progressive muscular atrophy (LMN onset) Questions Wasting Classification • Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis • Progressive Bulbar Palsy • Progressive Muscular Atrophy • Primary Lateral Sclerosis • Multifocal Motor Neuropathy • Spinal Muscular Atrophy • Kennedy’s Disease • Monomelic Amyotrophy • Brachial Amyotrophic Diplegia El Escorial Criteria for Diagnosis Tongue fasiculations Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis • ‘Typical’ presentation (60%+) • Usually one limb initially – Foot drop – Clumsy weak hand – May complain of cramps • Gradual progression over months • May be some wasting at presentation • Usually fasiculations (often more widespread) • Brisk reflexes, extensor plantars • No sensory signs; MAY occasionally be mild symptoms • Relentless progression, noticable over weeks/ months Bulbar MND • Approximately 30% of cases • Onset with dysarthria, dysphagia • Bulbar and pseudobulbar symptoms • On examination – Dysarthria – -

Jemds.Com Case Report

Jemds.com Case Report HIRAYAMA DISEASE Shaik Sulaiman Meeron1, Senthilkumaran Arjunan2, Murugarajan Singaram3 1Associate Professor, Department of Medicine, Chengalpattu Medical College. 2Assistant Professor, Department of Medicine, Chengalpattu Medical College. 3Junior Resident, Department of Medicine, Chengalpattu Medical College. ABSTRACT Hirayama’s disease, also known as Monomelic Amyotrophy (MMA), juvenile non-progressive amyotrophy, Sobue disease. It is rare and benign condition. It is a focal, lower motor neuron type of disorder, which occurs mainly in young males. Age of onset, it is first seen most commonly in people in their second and third decades. Geographically, it is seen most commonly in Asian countries like India and Japan. Cause of this disease is unknown in most cases. MRI of cervical spine in flexion is the investigation of choice, which will reveal the cardinal features of Hirayama disease. CASE REPORT 20 years old male came with the complaints of tremors of both hands more of right hand and weakness and wasting of right hand, which is slowly progressive for past 6 months. Lower limbs had no abnormality with normal deep tendon reflexes. On examination, there was wasting and weakness of hypothenar and interosseous muscles of right hand. MRI showed thinning of cord from C5 to C7 level. Proximal epidural fat and tiny flow voids with anterior migration of the posterior dural layer at C5-7 level on flexion MRI. Based on these features a diagnosis of focal amyotrophy was made. A cervical collar was prescribed and patient is under regular follow-up. CONCLUSION Hirayama disease is a rare self-limiting disease. Early diagnosis is necessary as the use of a simple cervical collar which will prevent neck flexion, has been shown to stop the progression. -

Case Report Hirayama Disease: a Rare Disease with Unusual Features

Hindawi Publishing Corporation Case Reports in Neurological Medicine Volume 2016, Article ID 5839761, 4 pages http://dx.doi.org/10.1155/2016/5839761 Case Report Hirayama Disease: A Rare Disease with Unusual Features S. Anuradha and Vanlalmalsawmdawngliana Fanai Department of Medicine, Maulana Azad Medical College and Associated Hospitals, New Delhi 110002, India Correspondence should be addressed to S. Anuradha; [email protected] Received 28 August 2016; Accepted 4 December 2016 Academic Editor: Dominic B. Fee Copyright © 2016 S. Anuradha and V. Fanai. This is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. Hirayama disease, also known as monomelic amyotrophy (MMA), is a rare cervical myelopathy that manifests itself as a self- limited, asymmetrical, slowly progressive atrophic weakness of the forearms and hands predominantly in young males. The forward displacement of the posterior dura of the lower cervical dural canal during neck flexion has been postulated to lead to lower cervical cord atrophy with asymmetric flattening. We report a case of Hirayama disease in a 25-year-old Indian man presenting with gradually progressive asymmetrical weakness and wasting of both hands and forearms along with unusual features of autonomic dysfunction and upper motor neuron lesion. 1. Introduction both lower limbs within the next 6 months. The tremors resulted in severe disability in performing activities involving Hirayama disease (HD), a rare neurological condition, is his hands like writing. He also developed excessive sweating a sporadic juvenile muscular atrophy of the distal upper of both palms. -

Monomelic Atrophy

THE CANADIAN JOURNAL OF NEUROLOGICAL SCIENCES Monomelic Atrophy J. Oryema, P. Ashby and S. Spiegel ABSTRACT: Weakness of distal muscles of one upper limb which progresses over 1 year and then appears to arrest ("monomelic amyotrophy") has been reported mainly in Japan and India. We report 5 cases of a similar syndrome occurring in Canada. In our cases the wasting affected the forearm muscles of one upper limb (sparing brachioradialis and extensor carpi radialis). There was minimal wasting and electromyographic changes in the opposite upper limb. The CT myelogram showed unilateral wasting of the cervical cord. RESUME: Atrophie monomelique Une faiblesse musculaire distale au niveau d'un membre superieur, qui evolue sur une periode d'un an et qui semble ensuite arreter de progresser ("amyotrophic monomelique") a ete rapportee surtout au Japon et aux Indes. Nous rapportons 5 cas d'un syndrome similaire survenus au Canada. Chez nos cas, 1'atrophie atteignait les muscles de l'avant-bras d'un membre superieur (epargnant le long supinateur et le radial). II y avait peu d'atrophie et de changements electromyographiques dans le membre superieur oppose. Le myelogramme par CT a montre une atrophie unilaterale de la moelle epiniere cervicale. Can. J. Neurol. Sci. 1990; 17:124-130 Hirayama et al1 were the first to describe a condition in It is not known whether the condition is less frequent in which there was progressive wasting and weakness of the distal North America or is simply not reported. We report 5 typical muscles of one upper limb which became arrested after 1 - 2 cases attending a routine clinical EMG laboratory over a 2 year years. -

Role in Intraoperative Neuromonitoring Sandip C

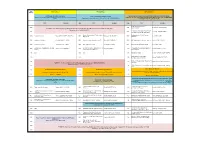

TIME VIRTUAL HALL 1 VIRTUAL HALL 2 VIRTUAL HALL 3 (GMT+8) SYMPOSIUM: MOVEMENT DISORDER WORKSHOP: INTRAOPERATIVE NEUROPHYSIOLOGICAL MONITORING (NIOM) SYMPOSIUM: MOTOR NEURON DISEASE Chairpersons: Norlinah MOHAMED IBRAHIM (MALAYSIA) and Mathew ALEXANDER Programme Directors: Kyung-Seok PARK (SOUTH KOREA) and Yew-Long LO (SINGAPORE) Chaipersons: Rabani REMLI (MALAYSIA) and Sheila AGUSTINI (INDONESIA) (INDIA) Chairperson: Khean Jin GOH (MALAYSIA) TOPIC SPEAKER TIME TOPIC SPEAKER TIME TOPIC SPEAKER SSEP: Role in Intraoperative 0800 0800 Sandip CHATTERJEE (INDIA) Neuromonitoring PLENARY 3: Clinical Neurophysiology of Movement Disorders: Example of Functional Movement Disorders - Mark HALLETT (USA) Chairperson: Shen-Yang LIM (MALAYSIA) Intraoperative Monitoring of Motor Evoked 0830 0830 Yew-Long LO (SINGAPORE) Potentials: Physiology and Applications Monomelic Amyotrophy - Experience from a Brainstem Auditory Evoked Potential 0900 Evaluation of Tremor Pattamon PANYAKAEW (THAILAND) 0900 Atcharayam NALINI (INDIA) 0910 Aatif HUSAIN (USA) Large Cohort Monitoring 0935 Evaluation of Myoclonus Ritsuko HANAJIMA (JAPAN) 0930 Neurophysiological Biomarkers in ALS Steve VUCIC (AUSTRALIA) 0935 EMG Monitoring: Free-Run and Triggered Tsui-Fen YANG (TAIWAN) 1000 Evaluation of Dystonia Pramod Kumar PAL (INDIA) 1000 Role of Ultrasound in ALS Yu-ichi NOTO (JAPAN) 0955 Electroencephalographic Monitoring Aatif HUSAIN (USA) Sensori-motor Organisation in Focal Hand Electrophysiological Characteristics of NMJ Intraoperative Monitoring and Mapping of 1030 Mathew ALEXANDER -

Hirayama Disease- a Classic Case with Typical MRI Findings

Jemds.com Case Report Hirayama Disease- A Classic Case with Typical MRI Findings C. Sable1, Girish N. K2, V. M. Kulkarni3, P. Sharma4 1Department of Radiodiagnosis, Dr. D. Y. Patil Medical College, Pune, Maharashtra, India. 2Department of Radiodiagnosis, Dr. D. Y. Patil Medical College, Pune, Maharashtra, India. 3Department of Radiodiagnosis, Dr. D. Y. Patil Medical College, Pune, Maharashtra, India. 4Department of Radiodiagnosis, Dr. D. Y. Patil Medical College, Pune, Maharashtra, India. INTRODUCTION Hirayama disease is also called monomelic amyotrophy or juvenile spinal muscular Corresponding Author: Dr. Girish N. K. atrophy of the distal upper extremity. There is anterior displacement of dural sac MHADA Colony, during cervical flexion which impairs the anterior horn cells of the distal cervical Sharayu Building, 304 4B, spinal cord secondarily.[1,2] it mostly affects males in 2nd - 3rd decades. Clinically, the Pimpri, Pune-411018, patient mainly presents with unilateral or bilateral muscular atrophy and weakness Maharashtra, India. of the forearms and hands which is insidious in onset and is slowly progressive. E-mail: [email protected] Rarely, autonomic involvement, sensory disturbance and upper motor neuron (UMN) signs like hyperreflexia and hypertonia maybe seen.[3] Pathogenic mechanism is that DOI: 10.14260/jemds/2019/731 there is marked asymmetric flattening of the lower cervical cord which is caused due Financial or Other Competing Interests: to forward displacement of the posterior wall of cervical canal in flexion.[4] the None. distinguishing feature of this disease is that after progression for 2 to 4 years it achieves a plateau with spontaneous stabilization.[5,6] It is most commonly seen in How to Cite This Article: Asian countries like India and Japan.[4,7,8] Aetiology of this disease in majority of cases Sable C, Girish NK, Kulkarni VM, et al. -

A Dictionary of Neurological Signs.Pdf

A DICTIONARY OF NEUROLOGICAL SIGNS THIRD EDITION A DICTIONARY OF NEUROLOGICAL SIGNS THIRD EDITION A.J. LARNER MA, MD, MRCP (UK), DHMSA Consultant Neurologist Walton Centre for Neurology and Neurosurgery, Liverpool Honorary Lecturer in Neuroscience, University of Liverpool Society of Apothecaries’ Honorary Lecturer in the History of Medicine, University of Liverpool Liverpool, U.K. 123 Andrew J. Larner MA MD MRCP (UK) DHMSA Walton Centre for Neurology & Neurosurgery Lower Lane L9 7LJ Liverpool, UK ISBN 978-1-4419-7094-7 e-ISBN 978-1-4419-7095-4 DOI 10.1007/978-1-4419-7095-4 Springer New York Dordrecht Heidelberg London Library of Congress Control Number: 2010937226 © Springer Science+Business Media, LLC 2001, 2006, 2011 All rights reserved. This work may not be translated or copied in whole or in part without the written permission of the publisher (Springer Science+Business Media, LLC, 233 Spring Street, New York, NY 10013, USA), except for brief excerpts in connection with reviews or scholarly analysis. Use in connection with any form of information storage and retrieval, electronic adaptation, computer software, or by similar or dissimilar methodology now known or hereafter developed is forbidden. The use in this publication of trade names, trademarks, service marks, and similar terms, even if they are not identified as such, is not to be taken as an expression of opinion as to whether or not they are subject to proprietary rights. While the advice and information in this book are believed to be true and accurate at the date of going to press, neither the authors nor the editors nor the publisher can accept any legal responsibility for any errors or omissions that may be made. -

Madras Pattern Ofmotor Neuron Disease in South India 775 Patients There Was Convincing Evidence of Pyramidal 51- Signs

J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry: first published as 10.1136/jnnp.51.6.773 on 1 June 1988. Downloaded from Journal ofNeurology, Neurosurgery, and Psychiatry 1988;51:773-777 Madras pattern of motor neuron disease in South India MGOURIE-DEVI, TGSURESH From the Department ofNeurology, National Institute ofMental Health and Neurosciences, Bangalore, India SUMMARY This paper presents the clinical features in 12 patients with the Madras pattern of motor neuron disease (MMND) seen over a period of 10 years. Ten of the patients were from other parts of South India, outside Madras. Young age at onset, sporadic occurrence, sensorineural deafness, bulbar palsy, diffuse atrophy with weakness of limbs and progressive but benign course were the striking features. Electromyography revealed chronic partial denervation. MMND formed 3 7% of all forms of motor neuron disease. Although isolated cases have been seen elsewhere in India, this is the first report of a large number of patients of MMND seen outside Madras (Tamil Nadu). Recognition of this clinical syndrome is of importance for prognostication and as well for search of possible aetiological factors. Protected by copyright. A sub group of motor neuron disease in the younger Methods age group was described from Madras, India by Meenakshisundaram et al in 1970.1 Subsequently this The National Institute of Mental Health & Neurosciences, condition has been termed the Madras Pattern of Bangalore, South India, is a major centre in India and receives patients not only from the State of Karnataka where Motor Neuron Disease (MMND) and the character- it is situated but also from other states in the country.