Ten Questions Concerning Air Fresheners and Indoor Built Environments

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Characterization of Air Freshener Emission: the Potential Health Effects

The Journal of Toxicological Sciences (J. Toxicol. Sci.) 535 Vol.40, No.5, 535-550, 2015 Review Characterization of air freshener emission: the potential health effects Sanghwa Kim1, 2,*, Seong-Ho Hong1,*, Choon-Keun Bong3 and Myung-Haing Cho1,2,4,5,6 1Laboratory of Toxicology, BK21 PLUS Program for Creative Veterinary Science Research, Research Institute for Veterinary Science and College of Veterinary Medicine, Seoul National University, Seoul 151-742, Korea 2Graduate Group of Tumor Biology, Seoul National University, Seoul 151-742, Korea 3Green Solus, Seoul 172-775, Korea 4Graduate School of Convergence Science and Technology, Seoul National University, Suwon 443-270, Korea 5Advanced Institute of Convergence Technology, Seoul National University, Suwon 443-270, Korea 6Institute of GreenBio Science Technology, Seoul National University, Pyeongchang-gun, Gangwon-do, 232-916, Korea (Received March 30, 2015; Accepted June 3, 2015) ABSTRACT — Air freshener could be one of the multiple sources that release volatile organic com- pounds (VOCs) into the indoor environment. The use of these products may be associated with an increase in the measured level of terpene, such as xylene and other volatile air freshener components, including aldehydes, and esters. Air freshener is usually used indoors, and thus some compounds emit- ted from air freshener may have potentially harmful health impacts, including sensory irritation, respira- tory symptoms, and dysfunction of the lungs. The constituents of air fresheners can react with ozone to produce secondary pollutants such as formaldehyde, secondary organic aerosol (SOA), oxidative product, and ultrafine particles. These pollutants then adversely affect human health, in many ways such as dam- age to the central nervous system, alteration of hormone levels, etc. -

Opinion on Air Fresheners, SCHER Plenary, 27 January 2006

EUROPEAN COMMISSION HEALTH & CONSUMER PROTECTION DIRECTORATE-GENERAL Directorate C - Public Health and Risk Assessment C7 - Risk assessment SCIENTIFIC COMMITTEE ON HEALTH AND ENVIRONMENTAL RISKS SCHER Opinion on the report “Emission of chemicals by air fresheners Tests on 74 consumer products sold in Europe” (BEUC report January 2005) Adopted by the SCHER during the 9th plenary of 27 January 2006 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. BACKGROUND......................................................................................................... 3 2. TERMS OF REFERENCE.......................................................................................... 3 3. GENERAL COMMENTS........................................................................................... 4 4. SPECIFIC COMMENTS............................................................................................ 5 4.1. Exposure assessment......................................................................................... 5 4.1.1. The BEUC study ................................................................................. 5 4.1.2. VOCs................................................................................................... 5 4.1.3. Allergens ............................................................................................. 6 4.1.4. Benzene ............................................................................................... 6 4.1.5. Formaldehyde...................................................................................... 6 4.1.6. Terpenes -

2004-06-24 Chapter 7 California Consumer Products Regulations and Method 310 and Adoption of a Proposed Airborne

VII. HEALTH RISK AND NEEDS ASSESSMENT FOR THE AIRBORNE TOXIC CONTROL MEASURE FOR PARA-DICHLOROBENZENE SOLID AIR FRESHENERS AND TOILET/URINAL CARE PRODUCTS A. INTRODUCTION Para-dichlorobenzene (PDCB) is a chlorinated benzene compound designated by the International Agency for Research on Cancer to be possibly carcinogenic to humans (Group 2B). It is also a California Toxic Air Contaminant (TAC) and a federal Hazardous Air Pollutant. Humans are substantially exposed to this compound by breathing indoor air. The compound is widely used primarily as the air freshener in toilet and urinal deodorant blocks and also as the main ingredient in mothballs. Breath, blood, urine and even breast milk samples and adipose tissue from most persons in the United States show measurable levels of PDCB, which is indicative of its widespread use (see Subsection H.5. Body Burden). The U.S. Consumer Product Safety Commission and the U.S. EPA recommend that where possible, PDCB, and items to be protected against moths, should be placed in trunks or other containers that can be stored in areas that are separately ventilated from the home, such as attics and detached garages (CPSC-U.S. EPA, 2004). The Air Resources Board has followed the use of PDCB in air fresheners since 1991. At the time, PDCB toilet/urinal blocks were essentially the only urinal deodorizer available. While we recognized at the time that PDCB was a possible human carcinogen, little in the way of viable alternatives existed. Staff decided at the time to provide an exemption for PDCB air fresheners that were at least 98 percent pure, with the intention of following the health effects literature and watching for the availability of alternatives. -

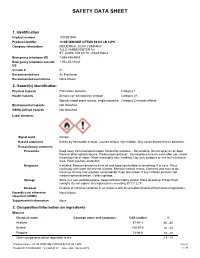

Safety Data Sheet

SAFETY DATA SHEET 1. Identification Product number 1000003949 Product identifier 10 OZ WINCIDE CITRUS S4103 LB 12PK Company information INDUSTRIAL SOAP COMPANY 722 S VANDEVENTER AV ST. LOUIS, MO 63110 United States Emergency telephone US 1-866-836-8855 Emergency telephone outside 1-952-852-4646 US Version # 01 Recommended use Air Freshener Recommended restrictions None known. 2. Hazard(s) identification Physical hazards Flammable aerosols Category 1 Health hazards Serious eye damage/eye irritation Category 2A Specific target organ toxicity, single exposure Category 3 narcotic effects Environmental hazards Not classified. OSHA defined hazards Not classified. Label elements Signal word Danger Hazard statement Extremely flammable aerosol. Causes serious eye irritation. May cause drowsiness or dizziness. Precautionary statement Prevention Keep away from heat/sparks/open flames/hot surfaces. - No smoking. Do not spray on an open flame or other ignition source. Pressurized container: Do not pierce or burn, even after use. Avoid breathing mist or vapor. Wash thoroughly after handling. Use only outdoors or in a well-ventilated area. Wear eye/face protection. Response If inhaled: Remove person to fresh air and keep comfortable for breathing. If in eyes: Rinse cautiously with water for several minutes. Remove contact lenses, if present and easy to do. Continue rinsing. Call a poison center/doctor if you feel unwell. If eye irritation persists: Get medical advice/attention. Collect spillage. Storage Store in a well-ventilated place. Keep container tightly closed. Store locked up. Protect from sunlight. Do not expose to temperatures exceeding 50°C/122°F. Disposal Dispose of contents/container in accordance with local/regional/national/international regulations. -

Fresh Thinking from Timemist®

Proof 2 10/27/10 2011 OP132 NP144 Flow: Sec 3 pg 1 Spreads with OP133 NP145 NON-PRICED VERSION Fresh Thinking From TimeMist® Quality. Coverage. Reliability. TimeMist® fragrances include natural, essential oils and only the highest-quality ingredients. We work with the finest oil vendors in the world to make sure that we are delivering the best product in the industry. Manufacturing TimeMist® products in the USA ensures that each fragrance measures up to the high standards of excellence we set. For over 25 years, the TimeMist® name has been synonymous with fresh thinking. TimeMist® invented the metered air freshening and air sanitizing categories and is the number one selling metered dispenser in the world. TimeMist is a registered trademark of Waterbury Companies, Inc. LS11_144_NP.indd 999 10/27/10 9:03:29 AM Proof 1 9/23/10 2011 OP133 NP145 Flow: Sec 3 pg 2 Spreads with OP132 NP144 NON-PRICED VERSION not priced 2009 LAGASSE 2_1 OP 82 CM/PM Sect 02_OdorControl Deodorizers Metered Dispensers & Refills Urinal & Bowl Odor Control LS11_145_NP.indd 111 9/23/10 8:48:02 AM Proof 1 11/2/10 Lagasse Supplier 2011 OP140 NP146 Flow: Sec 3 pg 17 Spreads with OP139 NP147 NON-PRICED VERSION Fan Dispensers & Gel Packs Sebreeze® AUTOMATIC ODOR CONTROL SYSTEMS • Long-lasting effective odor control for restrooms, hospitals, nursing homes and commercial buildings. Deodorizers Choose from two attractive dispenser units. Adjustable Fan Dispenser RCP 5114 CRE and Portable Fan Dispenser RCP 9C90 WHI dispense fragrance for 24-hour odor control. Each unit holds a battery-operated fragrance cassette (sold separately) for consistent fragrance release over a 30-day period. -

Clearing the Air

September 2007 NRDC Issue Paper Clearing the Air Hidden Hazards of Air Fresheners Authors Alison Cohen Natural Resources Defense Council Sarah Janssen, M.D., Ph.D., M.P.H. Natural Resources Defense Council Gina Solomon, M.D., M.P.H. Natural Resources Defense Council Clearing the Air: Hidden Hazards of Air Fresheners About NRDC The Natural Resources Defense Council is an international nonprofit environmental organization with more than 1.2 million members and online activists. Since 1970, our lawyers, scientists, and other environmental specialists have worked to protect the world’s natural resources, public health, and the environment. NRDC has offices in New York City, Washington, D.C., Los Angeles, San Francisco, Chicago, and Beijing. Visit us at www.nrdc.org. Acknowledgments The authors would like to thank Mark Valentini, Ph.D., Laboratory Director, Analytical Sciences, Inc., Petaluma, California, for doing the analysis of the samples, and Maria Minjares, Miriam Rotkin-Ellman, and Suzanne Vyborney for assistance with the project. We would also like to thank Tom Roush for his support of NRDC’s Science Center, which contributed heavily to this investigation and analysis. NRDC Director of Communications: Phil Gutis NRDC Marketing and Operations Director: Alexandra Kennaugh NRDC Publications Manager: Lisa Goffredi NRDC Publications Editor: Anthony Clark Production: Jon Prinsky Copyright 2007 by the Natural Resources Defense Council. For additional copies of this report, send $5.00 plus $3.95 shipping and handling to NRDC Reports Department, 40 West 20th Street, New York, NY 10011. California residents must add 7.5% sales tax. Please make checks payable to NRDC in U.S. -

Ultra-Fine Particles and Gaseous Volatile Organic Compound Exposures from the Reaction of Ozone and Car-Air Freshener During Metropolis Travel

Environ. Eng. Res. Vol. 12, No. 2, pp. 72~80, 2007 Korean Society of Environmental Engineers ULTRA-FINE PARTICLES AND GASEOUS VOLATILE ORGANIC COMPOUND EXPOSURES FROM THE REACTION OF OZONE AND CAR-AIR FRESHENER DURING METROPOLIS TRAVEL Rheo B. Lamorena1, Su-Mi Park2, Gwi-Nam Bae2, and Woojin Lee1,† 1Dept. of Civil and Environmental Engineering, Korea Advanced Institute of Science and Technology, 373-1 Daejon, Korea 2Environment and Process Technology, Korea Institute of Science and Technology, 130-650 Seoul, Korea (received June 2007, accepted May 2007) Abstract:Experiments were conducted to identify the emissions from the car air freshener and to identify the formation of ultra-fine particles and secondary gaseous compounds during the ozone-initiated oxidations with emitted VOCs. The identified primary constituents emitted from the car air freshener in this study were -pinene, -pinene, -cymene and limonene. Formation of ultra-fine particles (4.4 - 160 nm) was observed when ozone was injected into the chamber containing emitted monoterpenes from the air freshener. Particle number concentrations, particle mass concentrations, and surface concentrations were measured in time dependent experiments to describe the particle formation and growth within the chamber. The irritating secondary gaseous products formed during the ozone-initiated reactions include formaldehyde, acetaldehyde, acrolein, acetone, and propionaldehyde. Ozone concentration (50 and 100 ppb) and temperature (30 and 40 °C) significantly affect the formation of particles and gaseous products during the ozone-initiated reactions. The results obtained in this study provided an insight on the potential exposure of particles and irritating secondary products formed during the ozone-initiated reaction to passengers in confined spaces. -

Catalytic Air Freshening Diffusers Based on Isopropyl Alcohol - a Major Source of Acetone Indoors

Aerosol and Air Quality Research, 14: 177–184, 2014 Copyright © Taiwan Association for Aerosol Research ISSN: 1680-8584 print / 2071-1409 online doi: 10.4209/aaqr.2013.02.0051 Catalytic Air Freshening Diffusers Based on Isopropyl Alcohol - A Major Source of Acetone Indoors Otmar Geiss*, Carmen Del Cacho, Josefa Barrero-Moreno European Commission, Joint Research Centre, Institute for Health and Consumer Protection, Via E.Fermi 2749, 21027 Ispra (Va), Italy ABSTRACT Air fresheners are used in indoor environments for perfuming the ambience and/or masking unpleasant smells. There are several types of air fresheners on the market including those belonging to the family of catalytic diffusers. The fuel of these devices is frequently 2-methylpropanol, which, while operating, is oxidised to acetone. The acetone emission of a catalytic diffuser was measured for two fragrances under controlled laboratory conditions as well as in a private household. Emission rates were 530 mg/h and 660 mg/h respectively. Acetone concentrations of approximately 700 µg/m3 were measured in a private household three hours after the diffuser was extinguished. Besides isopropyl alcohol, one of the two fragrances contained 2-methylpropanol as a fuel component, which is oxidised to 2-methylpropanal. The emission rate for 2-methylpropanal was 11 mg/h. Catalytic diffusers containing isopropyl alcohol as fuel were identified as being a major indoor source of acetone. Although not a legal requirement, the secondary formation of acetone should be included in product information along with a list of product constituents. As an alternative, a less easily oxidisable solvent could be used. Keywords: Catalytic diffuser; Air freshener; Acetone, 2-Methylpropanal; IAQ. -

Air Pollution Control Regulation No. 31 Control of Volatile Organic Compounds from Consumer Products

STATE OF RHODE ISLAND AND PROVIDENCE PLANTATIONS DEPARTMENT OF ENVIRONMENTAL MANAGEMENT OFFICE OF AIR RESOURCES AIR POLLUTION CONTROL REGULATION NO. 31 CONTROL OF VOLATILE ORGANIC COMPOUNDS FROM CONSUMER PRODUCTS TABLE OF CONTENTS 31.1 Definitions...............................................................................................................1 31.2 Applicability and Exemptions...............................................................................28 31.3 VOC Content Limits..............................................................................................30 31.4 Labeling Requirements..........................................................................................40 31.5 Reporting Requirements........................................................................................41 31.6 Test Methods..........................................................................................................43 31.7 General Provisions.................................................................................................45 RI Regulation No. 31 - Page i RHODE ISLAND DEPARTMENT OF ENVIRONMENTAL MANAGEMENT OFFICE OF AIR RESOURCES AIR POLLUTION CONTROL REGULATION NO. 31 CONTROL OF VOLATILE ORGANIC COMPOUNDS FROM CONSUMER PRODUCTS 31. Control of Volatile Organic Compounds from Consumer Products 31.1 Definitions Unless otherwise expressly defined in this section, the terms used in this regulation shall be defined by reference to the Air Pollution Control General Definitions Regulation. As used in these -

Exposure to Volatile Organic Compounds and Effect on Neurobehavioral Function. Abhijeet Jagannath Bhanegaonkar East Tennessee State University

East Tennessee State University Digital Commons @ East Tennessee State University Electronic Theses and Dissertations Student Works 8-2005 Exposure to Volatile Organic Compounds and Effect on Neurobehavioral Function. Abhijeet Jagannath Bhanegaonkar East Tennessee State University Follow this and additional works at: https://dc.etsu.edu/etd Part of the Public Health Commons Recommended Citation Bhanegaonkar, Abhijeet Jagannath, "Exposure to Volatile Organic Compounds and Effect on Neurobehavioral Function." (2005). Electronic Theses and Dissertations. Paper 1053. https://dc.etsu.edu/etd/1053 This Thesis - Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Works at Digital Commons @ East Tennessee State University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ East Tennessee State University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Exposure to Volatile Organic Compounds and Effect on Neurobehavioral Function A thesis presented to the faculty of the Department of Public Health East Tennessee State University In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Master of Public Health in Health Administration by Abhijeet J. Bhanegaonkar August 2005 Dr. Tiejian Wu, Committee Chair Dr. Joanne Walker Flowers, Committee Member Dr. Mary Beth Hogan, Committee Member Keywords: Volatile Organic Compounds, Exposure, and Neurobehavioral effects ABSTRACT Exposure to Volatile Organic Compounds and Effect on Neurobehavioral Function by Abhijeet Bhanegaonkar Data of 1338 respondents from the Priority Toxicant Reference Range Study were analyzed to examine exposure to volatile organic compounds (VOCs). Self-reported contact to chemical products and blood concentrations of specific chemicals were analyzed. Neurobehavioral function was assessed by simple reaction time test (SRTT), symbol digit substitution test (SDST), and serial digit learning test (SDLT). -

Citizen Petition to EPA and CPSC Regarding Air Fresheners, September 15, 2007

September 19, 2007 Stephen Johnson, Administrator Environmental Protection Agency Ariel Rios Building 1200 Pennsylvania Avenue, NW Washington, D.C. 20460 Commissioner Thomas Moore U.S. Consumer Product Safety Commission 4330 East West Highway Bethesda, MD 20814 Re: Citizen Petition to EPA and CPSC Regarding Air Fresheners Dear Administrator Johnson and Commissioner Moore: Sierra Club, Alliance for Healthy Homes, the National Center for Healthy Housing, and the Natural Resources Defense Council (NRDC) petition the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) and the U.S. Consumer Product Safety Commission (CPSC) to undertake specific actions to assess fully the risk to the public from exposure to air fresheners and to take reasonable steps to reduce that risk. The petitioners are national organizations committed to protecting public health. Almost every American is exposed to air fresheners in some manner. Millions use air fresheners in their home. Outside their home, they are exposed in bathrooms where air fresheners are common. Many offices, retail stores, and restaurants use air fresheners as well. Often, the public is unaware of the nature, extent, and consequences of the exposure. American’s extensive exposure to air fresheners has grown more significant in recent years. According to a market research firm in New Jersey, total U.S. sales excluding home fragrance products such as incense and scented candles are expected to reach $1.72 billion – up 50 percent or $600 million since 2003.1 When incense is included, the U.S market was estimated at $2.9 billion in 20042 with market studies reporting further growth.3 1 Louise Story, “Sensing Opportunity in Dormitory Air,” New York Times, January 3, 2007, www.nytimes.com/2007/01/03/business/media/03fresh.html (July 26, 2007). -

Bunzl Catalog

Urinal Screens/Blocks URINAL SCREENS/BLOCKS A A. EXTRA DUTY URINAL SCREENS BIG D Cleans and deodorizes with every flush while protecting drain from debris. The cleaner/deodorizer block contains no acids or paradichlorobenzene. 22560689 689 1000 Flushes, Cherry 12/cs. 22560687 687 1000 Flushes, Cinnamon 12/cs. B B. MAGNUM URINAL SCREEN W/NON-PARA BLOCK BIG D For high-use areas. The design of this screen elevates the block to reduce contact with water. The larger block allows for discharge of more cleaners and deodorants with every flush. 100% water soluble. 22560644 644 2,500 Flushes, White Screen w/Blue Block 6/cs. C C. THE PEARL URINAL SCREEN BIG D Translucent in color with a clamshell-like design. Manufactured using a specially engineered copolymer that is impregnated with organic deodorizing compounds that are 200% stronger than traditional vinyl urinal screens. Anti-splash texture; preventing splash back and cross contamination of urine to other areas outside the restroom. Incredibly strong deodorizing D properties and VOC compliant in all 50 states. Translucent design allows total viewing of the drain to ensure it remains free-flowing. Collects debris before it clogs up the drain. 22560011 621 Melon Mist 60/cs. D. DEOD-O-SCREEN CCP E Vinyl urinal screen has 30 days of built-in deodorant. Universal shape fits most urinals. Disposable poly-glove included. Each screen is individually packaged. 27602164 1641 Blue (Floral) 72/cs. E. KLEEN-SCREEN URINAL SCREENS CCP 4 oz. enzymatic deodorant block contains surfactants and chelating agents to clean and deodorize for 30 days (up to 2,000 flushes).