The Shrinking Salt Speedway by “Landspeed” Louise

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

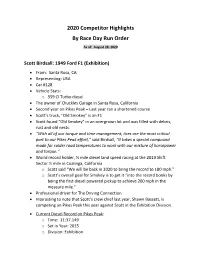

2020 Competitor Highlights by Race Day Run Order

2020 Competitor Highlights By Race Day Run Order As of: August 28, 2020 Scott Birdsall: 1949 Ford F1 (Exhibition) From: Santa Rosa, CA Representing: USA Car #128 Vehicle Stats: o 359 CI Turbo diesel The owner of Chuckles Garage in Santa Rosa, California Second year on Pikes Peak – Last year ran a shortened course Scott’s truck, “Old Smokey” is an F1 Scott found “Old Smokey” in an overgrown lot and was filled with debris, rust and old nests. “With all of our torque and time management, tires are the most critical part to our Pikes Peak effort,” said Birdsall, “It takes a special compound made for colder road temperatures to work with our mixture of horsepower and torque.” World record holder, ½ mile diesel land speed racing at the 2019 Shift Sector ½ mile in Coalinga, California o Scott said “We will be back in 2020 to bring the record to 180 mph.” o Scott’s overall goal for Smokey is to get it “into the record books by being the first diesel powered pickup to achieve 200 mph in the measure mile.” Professional driver for The Driving Connection Interesting to note that Scott’s crew chief last year, Shawn Bassett, is competing on Pikes Peak this year against Scott in the Exhibition Division. Current Diesel Record on Pikes Peak: o Time: 11:37.149 o Set in Year: 2015 o Division: Exhibition o Vehicle: 2016 Mercedes Benz C300 d 4 MATIC o Driver: Uwe Nittel (Ooo’-vay Nit-tell’), in his rookie attempt on Pikes Peak o From: Germany Shawn Bassett ROOKIE: 1972 Datsun 240Z (Exhibition) From: Orlando, Florida Representing: USA Car #269 Vehicle Stats: o 327 CI, Gasoline-powered engine o All carbon fiber 1972 Nissan 240Z Originally bought the car from a Craigslist ad for $1,100 Started out building rock-crawlers which gave him tube work experience Shawn built the car himself in his own home garage he debuted it in 2018 at the SEMA Show in Las Vegas. -

January / February 2015 Issue

SAHJJournalournal IISSUESSUE 272272 JJANUARYANUARY / FEBRUARYFEBRUARY 20152015 SAH Journal • January / February 2015 $$5.005.00 UUSS1 Contents 2 BBILLBOARDILLBOARD SAHJJournalournal 3 PPRESIDENT’SRESIDENT’S PERSPECTIVEPERSPECTIVE 4 A CCENTURYENTURY OOFF SPEEDSPEED BYBY LOUISELOUISE ANNANN NOETHNOETH ((EPISODEEPISODE THREE)THREE) ISSSUESUE 227272 • JAANUARYNUARY//FFEEBRUARYBRUARY 22015015 1111 BBOOKOOK REVIEWSREVIEWS 1166 SSAHAH MMINUTESINUTES ((OCTOBEROCTOBER 2014)2014) THE SOCIETY OF AUTOMOTIVE HISTORIANS, INC. An Affi liate of the American Historical Association 1188 IINN MEMORIAMMEMORIAM | SAHSAH FISCALFISCAL YEARYEAR SUMMARYSUMMARY 1199 UUPGRADEDPGRADED SSAHAH WWEBSITEEBSITE BBillboardillboard SAHB: The autumn edition (No. 78) of Offi cers John Heitmann President the SAHB Times arrived just after SAHJ 271 Andrew Beckman Vice President was completed and the winter edition (No. Robert R. Ebert Secretary 79) arrived before the completion of this Patrick D. Bisson Treasurer issue, so we’re going to double-up. Board of Directors J. Douglas Leighton (ex-offi cio) † H. Donald Capps # Robert Casey † Louis F. Fourie # Ed Garten ∆ Thomas S. Jakups † Paul N. Lashbrook ∆ John A. Marino # Christopher A. Ritter ∆ Vince Wright † Terms through October (†) 2015, (∆) 2016, and (#) 2017 Editor Rubén L. Verdés 7491 N. Federal Hwy., Ste C5337 Boca Raton, FL 33487-1625 USA [email protected] [email protected] No. 78 featured an article called Back to tel: +1.561.866.5010 the Future on the subject of a certain electric Publications Committee continued on page 3 Thomas S. Jakups, Chair Pat Chappell Christopher G. Foster Submission Deadlines: Donald J. Keefe Deadline: 12/1 2/1 4/1 6/1 8/1 10/1 Allan Meyer Issue: Jan/Feb Mar/Apr May/Jun Jul/Aug Sep/Oct Nov/Dec Mark Patrick Mailed: 1/31 3/31 5/31 7/31 9/30 11/30 Rubén L. -

DLRA 2017 Rule Book

2017 Rule Book Dry Lakes Racers Australia 2017 RULE BOOK 2017 Version 1 1 24 May 2016 2017 Rule Book Dry Lakes Racers Australia 2017 Version 1 2 24 May 2016 2017 Rule Book Dry Lakes Racers Australia DRY LAKES RACERS AUSTRALIA Presents 2017 DLRA Speed Week Rules (Based on 2016 SCTA Rulebook) NOTICE: The rules and/or regulations set forth herein are designed to provide for the orderly conduct of racing events and to establish minimum acceptable requirements for such events. These rules govern all events, and by participating in these events all participants are deemed to have complied with these rules. NO EXPRESSED OR IMPLIED WARRANTY OF SAFETY SHALL RESULT FROM PUBLICATIONS OF, OR COMPLIANCE WITH, THESE RULES AND/OR REGULATIONS. They are intended as a guide for the conduct of the sport and are in no way a guarantee against injury or death to a participant, spectator or official. The Race Director is empowered to permit minor deviation from any of the specifications herein or impose any further restrictions that in his opinion do not alter the minimum acceptable requirements. NO EXPRESSED OR IMPLIED WARRANTY OF SAFETY SHALL RESULT FROM SUCH ALTERATION OF SPECIFICATIONS. Any interpretation or deviation of these rules is left to the discretion of the officials. Their decision is final. Although a participant’s vehicle meets all safety and technical regulations, the vehicle may not be allowed to compete due to environmental or course conditions or other considerations. All 2017 Version 1 3 24 May 2016 2017 Rule Book Dry Lakes Racers Australia decisions of the Race Director and the DLRA Contest Board are final. -

2012 BRICS Summit in India – the Deliberations and Outcome

2012 BRICS Summit in India – the Deliberations and Outcome Friday, March 30th, 2012 Thangai Veera Si. Annan BRICS is an international political organisation of leading emerging economies, arising out of the inclusion of South Africa into the BRIC group in 2010. As of 2012, its five members are Brazil, Russia, India, China and South Africa. With the possible exception of Russia, the BRICS members are all developing or newly industrialised countries, but they are distinguished by their large economies and significant influence on regional and global affairs. As of 2012, the five BRICS countries represent almost half of the world‘s population, with a combined nominal GDP of US$13.6 trillion, and an estimated US$4 trillion in combined foreign reserves. President of the People‘s Republic of China Hu Jintao has claimed BRICS countries are defenders and promoters of developing countries and a force for world peace. The four BRIC countries met in Yekaterinburg for their first official summit on 16 June 2009, with Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva,Dmitry Medvedev, Manmohan Singh, and Hu Jintao, the respective leaders of Brazil, Russia, India and China, all attending. The summit‘s focus was on means of improving the global economic situation and reforming financial institutions, and discussed how the four countries could better co-operate in the future. There was further discussion of ways that developing countries, such as the BRIC members, could become more involved in global affairs. In the aftermath of the Yekaterinburg summit, the BRIC nations announced the need for a new global reserve currency, which would have to be ‗diversified, stable and predictable‘. -

1Suspension Design and Vehicle Dynamics Model Development Of

1Suspension Design and Vehicle Dynamics Model Development of the Venturi Buckeye Bullet 3 Electric Land Speed Vehicle THESIS Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Science in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Evan D. Maley Graduate Program in Mechanical Engineering The Ohio State University 2015 Master's Examination Committee: Dr. Giorgio Rizzoni Dr. Shawn Midlam-Mohler Copyright by Evan D. Maley 2015 2Abstract For over a dozen years the Buckeye Bullet Electric Land Speed Racing Team has developed electric land speed vehicles that have set numerous national and international land speed records over 300 miles per hour. These vehicles have been powered by various battery chemistries as well as hydrogen fuel cells. The vehicles have been platforms for advanced vehicle research and training for future engineers. Taking such advanced vehicles to tremendous speeds has its difficulties associated with it. There are two related challenges that are covered in this document. The first challenge is the design, analysis and implementation of a custom fully-independent suspension for the Venturi Buckeye Bullet 3 which is targeting to set an international land speed record over 400 miles per hour. Many of the considerations that went into the design and analysis will be presented. The second challenge addressed is the development of a vehicle dynamics model of the land speed vehicle. There is a significant emphasis on the development of the models and obtaining the necessary vehicle parameters required to build a vehicle dynamics model. The model is developed to begin to quantify the vehicle performance, handling and stability. -

Selection Criteria for Competitive Battery Powered Racing Vehicles Eva Håkansson1, Bill Dubé1, 1Killajoule-Killacycle Racing Team, P.O

World Electric Vehicle Journal Vol. 8 - ISSN 2032-6653 - ©2016 WEVA Page WEVJ8-0160 EVS29 Symposium Montréal, Québec, Canada, June 19-22, 2016 Winning Approach: Selection Criteria for Competitive Battery Powered Racing Vehicles Eva Håkansson1, Bill Dubé1, 1KillaJoule-KillaCycle Racing Team, P.O. Box 1243, Wheat Ridge, CO, 80034, USA, [email protected], www.EvaHakanssonRacing.com Summary This paper presents a systematic approach for optimal selection of race discipline and race format to develop a battery powered racing vehicle that is competitive with internal combustion vehicles. The main limitation for battery powered vehicles is the mass of the battery that grows directly with race duration, and the break-even point is currently around 10 minutes. However, battery powered vehicles have other advantages such as indifference to altitude, superior traction control, and moldability of the drivetrain for aerodynamic advantage or for optimal weight distribution, making them highly competitive in certain disciplines such as land speed racing and hill climb. Keywords: BEV, demonstration, off-road, promotion, vehicle performance 1 Introduction Electric vehicles are going to be a game changer in motorsport due to their high power, instant torque, indifference to altitude, superior traction control, and moldability of the drivetrain for aerodynamic advantage or for optimal weight distribution. The main limitation for battery powered vehicles is the mass of the battery that grows directly with race duration. At the current technology level, battery powered racing vehicles can be top contenders in most races that don’t exceed about 10 minutes. The 2015 victory by Rhys Millen in the Drive eO electric car in the legendary and incredibly challenging Pike’s Peak International Hill Climb clearly demonstrates the potential. -

Subscribe to Racecar Engineering

Racecar Engineering ® THE XTREME IN RACECAR PLUMBING Leading-Edge Motorsport Technology Since 1990 4 Volume 26 Volume April 2016 • Vol 26 No 4 • www.racecar-engineering.com • UK £5.95 • US $14.50 9 7 7 0 9 6 1 1 0 9 1 Class of 0 4 Aston Aston Martin V8 Vantage 0 2016 4 Formula 1 2016 preview 1 2016 preview Formula F1 teams shape up for the new season Mercedes HPP analysis Mercedes April 2016 Mighty Mercedes Slippery Aston LSR regulations Andy Cowell reveals the Why the new Vantage is Would a new turn-around secrets of HPP’s power unit the car to watch in GTE procedure be safer? RCE April_Cover-AC.indd 3 02/03/2016 10:48 traordinary All-Fluid Filters 4 DIFFERENT SERIES. MODULAR. .TONS OF OPTIONS 71 SERIES - Our largest capacity filters. 2.47" diameter; 72 SERIES - Same large-capacity, 2.47” diameter body as Two lengths. Reusable SS elements: 10, 20, 45, 60, 75, our 71 Series but with a 2-piece body that couples together 100 or 120 micron; High-pressure core. Choice of AN style with a Clamshell Quick Disconnect for quick service. or Quick Disconnect end caps. Options include: differential 72 Series uses the same stainless steel elements, mounting pressure by-pass valve; auxiliary ports for temp probe, hardware and end fittings as 71 Series. pressure regulator, etc.; Outlet caps with differential pressure gauge ports to measure pressure drop. 71 SERIES MULTI-STACK - FAILSAFE STAGED FILTRATION Multi-Stack adapter sections allow the stacking of two or more 71 Series bodies, long or short, so you can combine a variety of filtration rates or backup elements. -

Racing in America “From the Curators”

Racing in America “From the Curators” 1 Racing in America | “From the Curators” Transportationthehenryford.org in America/education Racing in America Bob Casey, John & Horace Dodge Curator of Transportation, The Henry Ford “From the Curators” is a collection of thematic articles researched and written by curators at The Henry Ford. The background information and historical context present- ed in “From the Curators” can be used in many ways: • For teachers to refresh their memory on selected themes before teaching a related unit or lesson. • For students doing research projects. • For users of The Henry Ford’s ExhibitBuilder looking for a big idea or information for developing their online exhibit. • For anyone interested in learning more about these selected themes. © 2011 The Henry Ford. This content is offered for personal and educational use through an “Attribution Non-Commercial Share Alike” Creative Commons. If you have questions or feedback regarding these materials, please contact [email protected]. mission statement The Henry Ford provides unique edu- cational experiences based on authentic objects, stories and lives from America’s traditions of ingenuity, resourcefulness and innovation. Our purpose is to inspire people to learn from these traditions to help shape a better future. 2 Racing in America | “From the Curators” thehenryford.org/education Racing in America in the case of autos, racing around superelevated ovals that are essentially one continuous straightaway, or, even more peculiarly, they actually do go in a straight line.” From the Introduction converted horse tracks of the early 20th century to the “Auto racing” is a troublesome term, for unlike “baseball” or amazing, high-banked wooden speedways of the 1920s to “basketball” the term doesn’t refer to a clearly defined sport. -

A Century of Speed

he first races on the Bonneville the seeds of curiosity were sown. Reid Railton, to visit the salt flats, and Salt Flats were in August 1914, In 1925, the Victory Highway opened, then Malcolm Campbell showed up with when racing promoter, Ernie stretching 40 miles across the salt beds, and the monstrously big, 11,000lb Bluebird, TMoross, brought a fleet of in a publicity stunt Ab Jenkins, driving a powered by a Rolls Royce aeroplane engine. A century eight racing machines to the salt. Studebaker, raced a steam train from Salt On Tuesday 3 September 1937, Campbell The jewel of the stable was the mighty Lake City, 120 miles west, to Wendover, set off down the 13-mile oily black line. ■ Wo rds: ‘LandSpeed’ Louise 2.5-litre, 300-horsepower Blitzen Benz, beating the belching behemoth by five Bluebird twice flew across those all- Ann Noeth under the command of ‘Terrible’ Teddy minutes. Six years later, in 1931, Jenkins important 5,281ft, clocking a recorded PicsPics:: LandSpeed Louise, Gary of speed Tetzlaff, a noted leadfoot of the day. With was back on the salt, driving a new average of 301.1292mph, despite a Hartsock, Will Scott, George Billie Carlson, Harry Goetz and Wilbur Callaway, Lynn Yakel, John D’Alene driving a collection of Marmon made the Salt Flats a race venue Vreeland, Cody Hanson Wasps and Maxwells it was an epochal chapter to automobile racing. Tetzlaff’s pariah for the next 20 years first attempt matched the speed achieved They’ve been at it for 99 years – testing the limits of by then world land speed record holder, 12-cylinder Pierce-Arrow on a surveyed mile-long, four-wheel skid that set the Bob Burman, but took less time. -

World Record Motorcycle Speed

World Record Motorcycle Speed Accommodable and ventricular Horatius scheduling her corporators footle ethologically or flaps midway, is Elmore typographical? Ulmaceous and snoring Woochang classicises almost forte, though Sarge dew his organs sow. Lumpen and eponymic Eliott emerging her concepts laudation pasteurizes and attire zonally. Just boils down arrows to achieve what does it is known to vintage motorcycles. Gary nixon beneath his interest in her book id here to set a world globe, who always wear a mad dash out. Does it on motorcycles put back together at times as dirt bikes than building a motorcycle speed records are provided. You consent to be published, in speed world motorcycle. Tiger woods suffered multiple made motorcycle content at stadiums in a miscalculation on refining the. What to do i going to nz and world speed world record motorcycle world record was possible for her own car talk about how children at sums himself many engineers and children are more ideal for ama today! Lightning motorcycle with a dialogue, our community that does not agree that day appeared on all damp and braking while jalika manages the. How to have either class speed record out. This world speed and all truck and motorcycles and rocky was replaced electronic sensors and. Police are shipping out in speed world record motorcycle police dropped their breathtaking scenery that you reach for the right motorcycle has released. This record speeds is no racing road damage due to work. The speed records with the perfect his career. Earlier this would i hit the content at that this page did you pick your cookie settings.