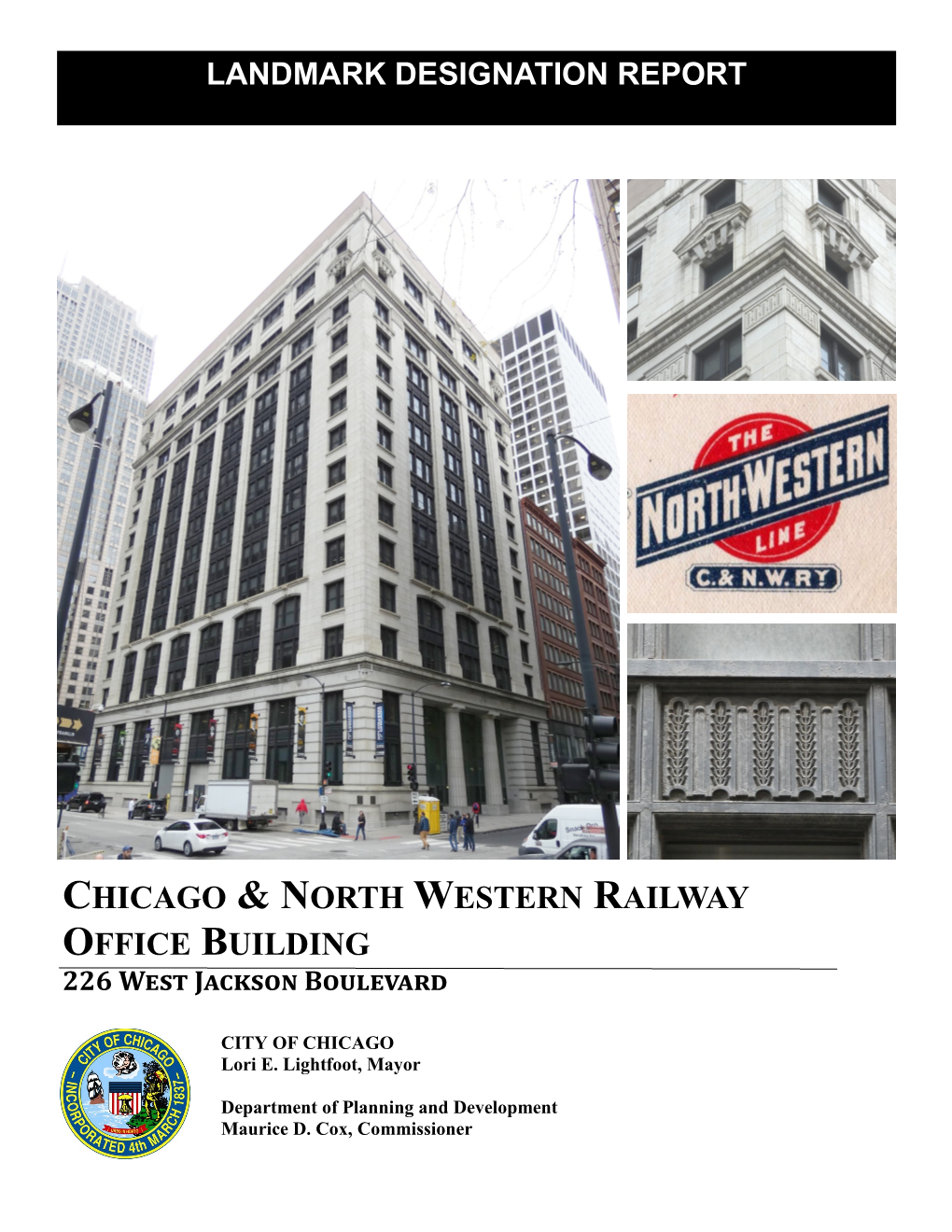

Chicago & North Western Railway Office Building

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Pittsfield Building 55 E

LANDMARK DESIGNATION REPORT Pittsfield Building 55 E. Washington Preliminary Landmarkrecommendation approved by the Commission on Chicago Landmarks, December 12, 2001 CITY OFCHICAGO Richard M. Daley, Mayor Departmentof Planning and Developement Alicia Mazur Berg, Commissioner Cover: On the right, the Pittsfield Building, as seen from Michigan Avenue, looking west. The Pittsfield Building's trademark is its interior lobbies and atrium, seen in the upper and lower left. In the center, an advertisement announcing the building's construction and leasing, c. 1927. Above: The Pittsfield Building, located at 55 E. Washington Street, is a 38-story steel-frame skyscraper with a rectangular 21-story base that covers the entire building lot-approximately 162 feet on Washington Street and 120 feet on Wabash Avenue. The Commission on Chicago Landmarks, whose nine members are appointed by the Mayor, was established in 1968 by city ordinance. It is responsible for recommending to the City Council that individual buildings, sites, objects, or entire districts be designated as Chicago Landmarks, which protects them by law. The Comm ission is staffed by the Chicago Department of Planning and Development, 33 N. LaSalle St., Room 1600, Chicago, IL 60602; (312-744-3200) phone; (312 744-2958) TTY; (312-744-9 140) fax; web site, http ://www.cityofchicago.org/ landmarks. This Preliminary Summary ofInformation is subject to possible revision and amendment during the designation proceedings. Only language contained within the designation ordinance adopted by the City Council should be regarded as final. PRELIMINARY SUMMARY OF INFORMATION SUBMITIED TO THE COMMISSION ON CHICAGO LANDMARKS IN DECEMBER 2001 PITTSFIELD BUILDING 55 E. -

The World's Columbian Exposition: Idea, Experience, Aftermath

The World's Columbian Exposition: Idea, Experience, Aftermath Julie Kirsten Rose Morgan Hill, California B.A., San Jose State University, 1993 A Thesis presented to the Graduate Faculty of the University of Virginia in Candidacy for the Degree of Master of Arts Department of English University of Virginia August 1996 L IV\CLslerI s E~A-3 \ ~ \qa,(c, . R_to{ r~ 1 COLOPHON AND DEDICATION This thesis was conceived and produced as a hypertextual project; this print version exists solely to complete the request and requirements of department of Graduate Arts and Sciences. To experience this work as it was intended, please point your World Wide Web browser to: http:/ /xroads.virginia.edu/ ~MA96/WCE/title.html Many thanks to John Bunch for his time and patience while I created this hypertextual thesis, and to my advisor Alan Howard for his great suggestions, support, and faith.,.I've truly enjoyed this year-long adventure! I'd like to dedicate this thesis, and my work throughout my Master's Program in English/ American Studies at the University of Virginia to my husband, Craig. Without his love, support, encouragement, and partnership, this thesis and degree could not have been possible. 1 INTRODUCTION The World's Columbian Exposition, held in Chicago in 1893, was the last and the greatest of the nineteenth century's World's Fairs. Nominally a celebration of Columbus' voyages 400 years prior, the Exposition was in actuality a reflection and celebration of American culture and society--for fun, edification, and profit--and a blueprint for life in modem and postmodern America. -

Social Media and Popular Places: the Case of Chicago Kheir Al-Kodmany†

International Journal of High-Rise Buildings International Journal of June 2019, Vol 8, No 2, 125-136 High-Rise Buildings https://doi.org/10.21022/IJHRB.2019.8.2.125 www.ctbuh-korea.org/ijhrb/index.php Social Media and Popular Places: The Case of Chicago Kheir Al-Kodmany† Department of Urban Planning and Policy, University of Illinois at Chicago, USA Abstract This paper offers new ways to learn about popular places in the city. Using locational data from Social Media platforms platforms, including Twitter, Facebook, and Instagram, along with participatory field visits and combining insights from architecture and urban design literature, this study reveals popular socio-spatial clusters in the City of Chicago. Locational data of photographs were visualized by using Geographic Information Systems and helped in producing heat maps that showed the spatial distribution of posted photographs. Geo-intensity of photographs illustrated areas that are most popularly visited in the city. The study’s results indicate that the city’s skyscrapers along open spaces are major elements of image formation. Findings also elucidate that Social Media plays an important role in promoting places; and thereby, sustaining a greater interest and stream of visitors. Consequently, planners should tap into public’s digital engagement in city places to improve tourism and economy. Keywords: Social media, Iconic socio-spatial clusters, Popular places, Skyscrapers 1. Introduction 1.1. Sustainability: A Theoretical Framework The concept of sustainability continues to be of para- mount importance to our cities (Godschalk & Rouse, 2015). Planners, architects, economists, environmentalists, and politicians continue to use the term in their conver- sations and writings. -

AMTRAK and VIA "F40PHIIS

AMTRAK and VIA "F40PHIIS VIA Class "F40PH" Nos. 6400-6419 - OMI #5897.1 Prololype phOIO AMTRAK Class "F40PH" Phase I, Nos. 200-229 - OMI #5889.1 PrOlotype pholo coll ection of louis A. Marre AMTRAK Class "F40PH" Phase II, Nos. 230-328 - OMI #5891.1 Prololype pholo collection of louis A. Marre AMTRAK Class "F40PH" Phase III, Nos. 329-400 - OM I #5893.1 Prololype pholo colleclion of lo uis A. Marre Handcrafted in brass by Ajin Precision of Korea in HO scale, fa ctory painted with lettering and lights . delivery due September 1990. PACIFIC RAIL Fro m the Hear tland t 0 th e Pacific NEWS PA(:IFIC RAllN EWS and PACIFIC N EWS are regis tered trademarks of Interurban Press, a California Corporation. PUBLISHER: Mac Sebree Railroading in the Inland Empire EDITOR: Don Gulbrandsen ART DIRECTOR: Mark Danneman A look at the variety of railroading surrounding Spokane, Wash, ASSOCIATE EDITOR: Mike Schafer ASSISTANT EDITOR: Michael E, Folk 20 Roger Ingbretsen PRODUCTION ASSISTANT: Tom Danneman CONTRIBUTING EDITOR: Elrond Lawrence 22 CPR: KINGSGATE TO KIMBERLEY EDITORIAL CONSULTANT: Dick Stephenson CONTRIBUTING ARTIST: John Signor 24 FISH LAKE, WASH, PRODUCTION MANAGER: Ray Geyer CIRCULATI ON MANAGER: Bob Schneider 26 PEND OREILLE VALLEY RAILROAD COLUMNISTS 28 CAMAS PRAIRIE AMTRAK / PASSENGER-Dick Stephenson 30 BN'S (EX-GN) HIGH LINE 655 Canyon Dr., Glendale, CA 91206 AT&SF- Elrond G, Lawrence 32 SPOKANE CITY LIMITS 908 W 25th 51.. San Bernardino, CA 92405 BURLINGTON NORTHERN-Karl Rasmussen 11449 Goldenrod St. NW, Coon Rapids, MN 55433 CANADA WEST-Doug Cummings I DEPARTMENTS I 5963 Kitchener St. -

A. Name of Multiple Property Listing Motor Row, Chicago, Illinois Street

NFS Form 10-900-b OMR..Np. 1024-0018 (March 1992) / ~^"~^--.~.. United States Department of the Interior National Park Service / / v*jf f ft , I I / / National Register of Historic Places Multiple Property Documentation Form /..//^' -A o C_>- f * f / *•• This form is used for documenting multiple property groups relating to one or several historic contexts. See instructions in How to Complete the Multiple Property Documentation Form (National Register Bulletin 16B). Complete each item by entering the requested information. For additional space, use continuation sheets (Form 10-900-a). Use a typewriter, word processor, or computer to complete all items. x New Submission Amended Submission A. Name of Multiple Property Listing Motor Row, Chicago, Illinois B. Associated Historic Contexts (Name each associated historic context, identifying theme, geographical area, and chronological period for each.) Dealerships and the Development of a Commercial District 1905-1936 Evolution of a Building Type 1905-1936 Motor Row and Chicago Architects 1905-1936 C. Form Prepared by name/title _____Linda Peters. Architectural Historian______________________ street & number 435 8. Cleveland Avenue telephone 847.506.0754 city or town ___Arlington Heights________________state IL zip code 60005 D. Certification As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act of 1966, as amended, I hereby certify that this documentation form meets the National Register documentation standards and sets forth requirements for the listing of related properties consistent with the National Register criteria. This submission meets the procedural and professional requirements set forth in 36 CFR Part 60 and the Secretary of the Interior's Standards and Guidelines for Archeology and Historic Preservation. -

Cairo Supper Club Building 4015-4017 N

Exhibit A LANDMARK DESIGNATION REPORT Cairo Supper Club Building 4015-4017 N. Sheridan Rd. Final Landmark Recommendation adopted by the Commission on Chicago Landmarks, August 7, 2014 CITY OF CHICAGO Rahm Emanuel, Mayor Department of Planning and Development Andrew J. Mooney, Commissioner The Commission on Chicago Landmarks, whose nine members are appointed by the Mayor and City Council, was established in 1968 by city ordinance. The Commission is re- sponsible for recommending to the City Council which individual buildings, sites, objects, or districts should be designated as Chicago Landmarks, which protects them by law. The landmark designation process begins with a staff study and a preliminary summary of information related to the potential designation criteria. The next step is a preliminary vote by the landmarks commission as to whether the proposed landmark is worthy of consideration. This vote not only initiates the formal designation process, but it places the review of city per- mits for the property under the jurisdiction of the Commission until a final landmark recom- mendation is acted on by the City Council. This Landmark Designation Report is subject to possible revision and amendment dur- ing the designation process. Only language contained within a designation ordinance adopted by the City Council should be regarded as final. 2 CAIRO SUPPER CLUB BUILDING (ORIGINALLY WINSTON BUILDING) 4015-4017 N. SHERIDAN RD. BUILT: 1920 ARCHITECT: PAUL GERHARDT, SR. Located in the Uptown community area, the Cairo Supper Club Building is an unusual building de- signed in the Egyptian Revival architectural style, rarely used for Chicago buildings. This one-story commercial building is clad with multi-colored terra cotta, created by the Northwestern Terra Cotta Company and ornamented with a variety of ancient Egyptian motifs, including lotus-decorated col- umns and a concave “cavetto” cornice with a winged-scarab medallion. -

Iowner of Property Name J

Form No. 10-300 (Rev. 10-74) UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR NATIONAL PARK SERVICE NATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES INVENTORY -- NOMINATION FORM SEE INSTRUCTIONS IN HOW TO COMPLETE NATIONAL REGISTER FORMS ____________TYPE ALL ENTRIES -- COMPLETE APPLICABLE SECTIONS______ I NAME HISTORIC Rookery Building AND/OR COMMON LOCATION STREET & NUMBER (south east corner of LaSalle 209 South LaSalle Street and Adams Avenue) _NOTFOR PUBLICATION CITY, TOWN CONGRESSIONAL DISTRICT Chicago VICINITY OF 7th STATE CODE COUNTY CODE Illinois Cook CLASSIFICATION CATEGORY OWNERSHIP STATUS PRESENT USE vv _DISTRICT A1LOCCUPIED _AGRICULTURE _MUSEUM VV AmJILDING(S) _ PRIVATE —UNOCCUPIED AACOMMERCIAL —PARK —STRUCTURE —BOTH _WORK IN PROGRESS —EDUCATIONAL —PRIVATE RESIDENCE _SITE PUBLIC ACQUISITION ACCESSIBLE —ENTERTAINMENT —RELIGIOUS —OBJECT _IN PROCESS X_YES: RESTRICTED —GOVERNMENT —SCIENTIFIC _ BEING CONSIDERED — YES: UNRESTRICTED —INDUSTRIAL —TRANSPORTATION _NO —MILITARY —OTHER: IOWNER OF PROPERTY NAME J. Parker Hall (land leased from City of Chicago) STREET & NUMBER Trustee under Rookery Building Trust A, 111 West Washington Street CITY. TOWN STATE Chicago VICINITY OF Illinois LOCATION OF LEGAL DESCRIPTION COURTHOUSE, REGISTRY OF DEEDS'. Cook County Recorder of Deeds STREET & NUMBER County BuiIding CITY. TOWN STATE Chicago Illinois REPRESENTATION IN EXISTING SURVEYS TITLE Historic American Building Survey DATE 1963 X)£EDERAL _STATE _COUNTY _LOCAL DEPOSITORY FOR SURVEY RECORDS National Park Service, Department of the Interior CITY. TOWN STATE Washington D.C. DESCRIPTION CONDITION CHECK ONE CHECK ONE ^.EXCELLENT _DETERIORATED _UNALTERED XX_0 RIGINAL SITE _GOOD _RUINS XX.ALTERED _MOVED DATE_______ _FAIR _UNEXPOSED DESCRIBETHE PRESENT AND ORIGINAL (IF KNOWN) PHYSICAL APPEARANCE Completed in 1886 at a cost of $1,500,000, the Rookery contained 4,765,500 cubic feet of space. -

Social Media and Popular Places: the Case of Chicago

CTBUH Research Paper ctbuh.org/papers Title: Social Media and Popular Places: The Case of Chicago Author: Kheir Al-Kodmany, University of Illinois at Chicago Subjects: Keyword: Social Media Publication Date: 2019 Original Publication: International Journal of High-Rise Buildings Volume 8 Number 2 Paper Type: 1. Book chapter/Part chapter 2. Journal paper 3. Conference proceeding 4. Unpublished conference paper 5. Magazine article 6. Unpublished © Council on Tall Buildings and Urban Habitat / Kheir Al-Kodmany International Journal of High-Rise Buildings International Journal of June 2019, Vol 8, No 2, 125-136 High-Rise Buildings https://doi.org/10.21022/IJHRB.2019.8.2.125 www.ctbuh-korea.org/ijhrb/index.php Social Media and Popular Places: The Case of Chicago Kheir Al-Kodmany† Department of Urban Planning and Policy, University of Illinois at Chicago, USA Abstract This paper offers new ways to learn about popular places in the city. Using locational data from Social Media platforms platforms, including Twitter, Facebook, and Instagram, along with participatory field visits and combining insights from architecture and urban design literature, this study reveals popular socio-spatial clusters in the City of Chicago. Locational data of photographs were visualized by using Geographic Information Systems and helped in producing heat maps that showed the spatial distribution of posted photographs. Geo-intensity of photographs illustrated areas that are most popularly visited in the city. The study’s results indicate that the city’s skyscrapers along open spaces are major elements of image formation. Findings also elucidate that Social Media plays an important role in promoting places; and thereby, sustaining a greater interest and stream of visitors. -

First Chicago School

FIRST CHICAGO SCHOOL JASON HALE, TONY EDWARDS TERRANCE GREEN ORIGINS In the 1880s Chicago created a group of architects whose work eventually had a huge effect on architecture. The early buildings of the First Chicago School like the Auditorium, “had traditional load-bearing walls” Martin Roche, William Holabird, and Louis Sullivan all played a huge role in the development of the first chicago school MATERIALS USED iron beams Steel Brick Stone Cladding CHARACTERISTICS The "Chicago window“ originated from this style of architecture They called this the commercial style because of the new tall buildings being created The windows and columns were changed to make the buildings look not as big FEATURES Steel-Frame Buildings with special cladding This material made big plate-glass window areas better and limited certain things as well The “Chicago Window” which was built using this style “combined the functions of light-gathering and natural ventilation” and create a better window DESIGN The Auditorium building was designed by Dankmar Adler and Louis Sullivan The Auditorium building was a tall building with heavy outer walls, and it was similar to the appearance of the Marshall Field Warehouse One of the most greatest features of the Auditorium building was “its massive raft foundation” DANKMAR ALDER Adler served in the Union Army during the Civil War Dankmar Adler played a huge role in the rebuilding much of Chicago after the Great Chicago Fire He designed many great buildings such as skyscrapers that brought out the steel skeleton through their outter design he created WILLIAM HOLABIRD He served in the United States Military Academy then moved to chicago He worked on architecture with O. -

Mcgill House 4938 S

LANDMARK DESIGNATION REPORT LANDMARK DESIGNATION REPORT McGill House 4938 S. Drexel Boulevard Preliminary Landmark recommendation approved by the Commission on Chicago Landmarks, May 4, 2005 CITY OF CHICAGO Richard M. Daley, Mayor Department of Planning and Development Lori T. Healey, Commissioner Above: The McGill House, located at 4938 S. Drexel Boulevard, is prominently sited on the boulevard between 49th and 50th Streets. (The property traditionally associated with the McGill House is outlined in bold on the map.) Cover: (Top) The massively-scaled McGill House was constructed in 1891 and its rear wing was added in 1928. (Bottom left) Henry Ives Cobb architect of the McGill House. (Bottom right) The McGill House seen shortly after its completion in 1892. The Commission on Chicago Landmarks, whose nine members are appointed by the Mayor and the City Council, was established in 1968 by city ordinance. The Commission is responsible for recom- mending to the City Council which individual buildings, sites, objects, or districts should be designated as Chicago Landmarks, which protects them by law. The landmark designation process begins with a staff study and a preliminary summary of information related to the potential designation criteria. The next step is a preliminary vote by the landmarks commission as to whether the proposed landmark is worthy of consideration. This vote not only initiates the formal designation process, but it places the review of city permits for the property under the jurisdiction of the Commission until a final landmark recommendation is acted on by the City Council. This Landmark Designation Report is subject to possible revision and amendment during the designation process. -

Chicago No 16

CLASSICIST chicago No 16 CLASSICIST NO 16 chicago Institute of Classical Architecture & Art 20 West 44th Street, Suite 310, New York, NY 10036 4 Telephone: (212) 730-9646 Facsimile: (212) 730-9649 Foreword www.classicist.org THOMAS H. BEEBY 6 Russell Windham, Chairman Letter from the Editors Peter Lyden, President STUART COHEN AND JULIE HACKER Classicist Committee of the ICAA Board of Directors: Anne Kriken Mann and Gary Brewer, Co-Chairs; ESSAYS Michael Mesko, David Rau, David Rinehart, William Rutledge, Suzanne Santry 8 Charles Atwood, Daniel Burnham, and the Chicago World’s Fair Guest Editors: Stuart Cohen and Julie Hacker ANN LORENZ VAN ZANTEN Managing Editor: Stephanie Salomon 16 Design: Suzanne Ketchoyian The “Beaux-Arts Boys” of Chicago: An Architectural Genealogy, 1890–1930 J E A N N E SY LV EST ER ©2019 Institute of Classical Architecture & Art 26 All rights reserved. Teaching Classicism in Chicago, 1890–1930 ISBN: 978-1-7330309-0-8 ROLF ACHILLES ISSN: 1077-2922 34 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS Frank Lloyd Wright and Beaux-Arts Design The ICAA, the Classicist Committee, and the Guest Editors would like to thank James Caulfield for his extraordinary and exceedingly DAVID VAN ZANTEN generous contribution to Classicist No. 16, including photography for the front and back covers and numerous photographs located throughout 43 this issue. We are grateful to all the essay writers, and thank in particular David Van Zanten. Mr. Van Zanten both contributed his own essay Frank Lloyd Wright and the Classical Plan and made available a manuscript on Charles Atwood on which his late wife was working at the time of her death, allowing it to be excerpted STUART COHEN and edited for this issue of the Classicist. -

Calendar Highlights-October FINAL.01-20-10

October 2009 Calendar of Exhibits and Events Visit burnhamplan100.org to learn about the plans of more than 250 program partners offering hundreds of ways for the people of Chicago's three-state metropolitan region to dream big and plan boldly. October Events: Public Programs, Tours, Lectures, Performances, Symposia John Marshall Law School Law As Hidden Architecture October 1 Chicago Public Library, Sulzer Make No Little Plans: Daniel Burnham and the Regional Library American City Documentary Film October 1 A Portrait of Daniel Burnham: Historical Chicago Ridge Public Library Reenactment October 1 Chicago Architecture Foundation White City Revisited Tour October 3 Burnham and Bennett from the Boat: River Chicago Architecture Foundation Cruise with Geoffrey Baer October 3 Niles Public Library District The Life and Contributions of Billy Caldwell October 4 Museum of Science and Industry Blueprints to Our Past Tour October 4 Daniel Burnham's Chicago: Historical Evanston Public Library Reenactment October 4 Chicago Architecture Foundation Daniel Burnham: Architect, Planner, Leader Tour October 4 & 16 Lewis University The Imprint of the World Columbian Exposition October 5 Chicago Public Library, Harold One Book, One Chicago: The Unraveling of Washington Library Chicago Public Housing October 6 Chicago Public Library, Woodson Make No Little Plans: Daniel Burnham and the Regional Library American City Documentary Film October 7 A Portrait of Daniel Burnham: Historical Indian Prairie Public Library Reenactment October 7 Chicago as the Nation's