Pontrelli Thesis Final1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

January to June 1915, Inclusive: Index to the One Hundredth Volume, Vol

DV. financial tillinurrt31 rk INCLUDING broni Bank & Quotation Section Railway & Industrial Section Electric Railway Section Railway Earnings Section Bankers' Convention Section State and City Section WEEKIN NEWSPAPER Representing the Industrial Interests of the United States. JANUARY TO JUNE, 1915, INCLUSIVE. VOLUME C 0 WILLIAM j DANA COMPANY, PUBLISHERS. FRONT, YINE & DEPEYSTER STS., NEW YORK. Digitized for FRASER http://fraser.stlouisfed.org/ Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis Copyrighted in 1915. according to Act of Coagresq. by WILLIAM 13, DANA COMPANY U office of Librarian of Congress. Washington D. C. Digitized for FRASER http://fraser.stlouisfed.org/ Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis JANUARY-JUNE, 1915.1 INDEX. LI t IN HEX TO THE ONE HUNDREDTH VOLUME. JANUARY 1 TO JUNE 30 1915. EDITORIAL AND COMMUNICATED ARTICLES. Page. Page. Page. B C Powers Sign Peace Treaty 1805 Bank Stock Sales__20, 116, 279, 370, 450, Brooklyn Trust Companies 590, 608 Acceptances, Arguments in Favor ot Use of 268 529, 602, 705, 785, 873, 953, 1050, 1141, Bryan, William J., Advice to Railroads_ __ 520 Adams, Charles Francis, Death of _ _1036, 1049 1227, 1320, 1409, 1481, 1647, 1723, 1806, Bryan, and Duty of German-Americans__2060 Administration and the Business Man_ _ _ _1547 1886, 1986, 2063, 2139 Bryan, William j., and Note to Germany.. _ 2059 Aeroplanes Not Considered War Vessels__ _ 526 Bank Stock Tax, N. Y. City Banks' Suit Bryan, William J., Resigns as Secretary of Africa. See Transvaal. for Return of 2063 State 1958, 1963, 1973, 1974 Agricultural Extension, Int. Harvester Bankers' Part in Nation's Development_ _ _2056 Building Operations First Quarter of 1915_ _ 1300 Co. -

Sonar and Lidar Investigation of Lineaments Offshore Between Central New England and the New England Seamounts, USA Ronald T

Document généré le 28 sept. 2021 20:15 Atlantic Geology Journal of the Atlantic Geoscience Society Revue de la Société Géoscientifique de l'Atlantique Sonar and LiDAR investigation of lineaments offshore between central New England and the New England seamounts, USA Ronald T. Marple et James D. Hurd, Jr. Volume 55, 2019 Résumé de l'article High-resolution multibeam echosounder (MBES) and light detection and URI : https://id.erudit.org/iderudit/1060415ar ranging (LiDAR) data, combined with regional gravity and aeromagnetic DOI : https://doi.org/10.4138/atlgeol.2019.002 anomaly maps of the western Gulf of Maine, reveal numerous lineaments between central New England and the New England seamounts. Most of these Aller au sommaire du numéro lineaments crosscut the NE-SWtrending accreted terranes, suggesting that they may be surface expressions of deep basement-rooted faults that have fractured upward through the overlying accreted terranes or may have formed by the Éditeur(s) upward push of magmas produced by the New England hotspot. The 1755 Cape Ann earthquake may have occurred on a fault associated with one of these Atlantic Geoscience Society lineaments. The MBES data also reveal a NW-SE-oriented scarp just offshore from Biddeford Pool, Maine (Biddeford Pool scarp), a 60-km-long, 20-km-wide ISSN Isles of Shoals lineament zone just offshore from southeastern New Hampshire, a 50-m-long zone of mostly low-lying, WNW-ESE-trending, 0843-5561 (imprimé) submerged ridge-like features and scarps east of Boston, Massachusetts, and a 1718-7885 (numérique) ~180-km-long, WNW-ESE-trending Olympus lineament zone that traverses the continental margin south of Georges Bank. -

SEISMIC DESIGN DECISION ANALYSIS Sponsored by National Science Foundation Research Applied to National Needs

SEISMIC DESIGN DECISION ANALYSIS Sponsored by National Science Foundation Research Applied to National Needs (RANN) Grant GI-27955 Report No. 32 SEISMIC DESIGN DECISIONS FOR THE COMMONWEALTH OF MASSACHUSETTS STATE BUILDING CODE by Frederick Krimgold June 1977 Publication No. MIT-CE R77-27 Order No. 575 Any opinions, findings, conclusions or recommendations expressed in this publication are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of the National Science Foundation. 50272 -101 REPORT DOCUMENTATION II~.REPORT NO. PAGE NSFjRA-770895 -----~ 4. Title and Subtitle S. Report Date Seismic Design Decisions for the Commonwealth of Massachusetts ~_June 1977 State Building Code (Seismic Design Decision Analysis Report 32 6. ·--~------~-·4 ~-------------------------------------------------------------7. Author(s) 8. .-~~---~-----------.-1Performing Organization Rept. No. F. Krim~old No. 32 9. Performing Organization Name and Address 10. Project/Task/Work Unit No. Massachusetts Institute of Technology _~_ MJT -CER77 -27 -- School of Engineering 11. Contract(C) or Grant(G) No_ Department of Civil Engineering (C) Cambridge, Massachusetts 02139 (G) GI27955 , _.. ~ .. -' . '- - 12. Sponsoring Organization Name and Address 13. Type of Report & Period Covered Engineering and Applied Science (EAS) National Science Foundation --~.. ~----~----.--- - _.- - -- 1800 G Street, N.W. 14. !-__Washington,---..:~_=-- D.C.______________________________ 20550 ~=_k-. • ••- -. .-.. ..- - ..• . - 15. Supplementary Notes Order No. 575 1-___________________________________________ -

"Testimony Concerning Seismology." Certificate of Svc Encl. Related Correspondence

- . _ % zevcp .. m o 4 . _ h < coCKETED .- utm0 .. - 'g ,7 FEB 191981 > . ^ ' Off:e of the Seestwy Docketing & Ser. fee / 4 Er:n:h E 4 g Public Service Company cf New Hampshire Seabrook Station Units 1 and 2 Docket Nos. 50-443 and 50-444 - Testimony Concerning Seismology by Richard J. Holt f for L , Public Service Company of New Hampshire . i . L. .j. .. 0 a . e 810saco7Ja __- - _ _ . % - Contents . - Page ' List of Figures and Table i . '- Comparison of the. Probability of the occurrence of an Earthquake Intensity on Rock Versus Soil 1 ,- ; - ; Linearity and Upper Limit of the Type Curves Shown by i Dr. Chinnery 2 Linearity of Curve 2 Regional Upper-Limit 4 , Definition of the SSE at Seabrook 5 . I Raferences 8 !. ' Figures 9 : i ' Table 1 21 Appendix 1 Excerpts rrom Earthquake Reports Al-1 , Appendix 2 Modified Mercalli Scale A2-1 ' Appendix 3 The New Madrid Earthquake A3-1 ,_ ! 4 e w $ y - a'-y--r - --gr++ y w r = &---*- y eav- --e-n-r - . - , -, Figures Page Figure 1 Increase of Intensity with Longitudinal 9 s Wave Velocity Figure 2 Probability of Intensity on Rock for 10 Region of Boston-New Hampshire Figure 3 Chinnery Curve for Mississippi Valley 11 1840-1969 Figure 4 Mississippi Valley with all 1811-1812 12 New Madrid Earthquakes Included .. Figure 5 Tarr (1977) Charleston, South Carolina 13 and South Carolina Earthquakes 1754-1975 Figure 5A Seismicity of the Charleston-Summerville 14 Area 15 i' Figure 5B Seismicity of the South Carolina Area -I ' Figure 6 La Malbaie Area Earthquakes 16 Figure 7 Linear and Quadratic Fit to Chinnery 17 Zones A & B , Figure 8 Chinnery Boston-New Hampshire Area Normal- 18 { 12cd to 1,000 km2 , Figure 9 Response Spectral Plot for Each Component 19 | of Strong Motion . -

US MAPS from Sketches by Theodore R

The Morristown Morris Township Library North Jersey History and Genealogy Center: Inventory of Maps and Surveys CALL NO. TITLE DATE SCALE SIZE DETAILS COPY NO. US MAPS From sketches by Theodore R. Davis; US-1-1 Bird's-eye view of Philadelphia 1872 Not given 32 x 23'' Copy 1 removed from Harper's Weekly 2/21/92. Sold by Tho. Basset in Fleet Street and US-1-2 A map of New England and New York 1650(?) 1" = 30 mi. 17"x21" Richard Chiswell in St. Paul's church Copy 1 Copy 2 yard. Text on reverse of Copy 1. A new and accurate map of the province of New York By J. Bew, Peter MasterRow. London. and part of the Jerseys, New England and Canada, US-1-3 1780 Not given 15"x11" Published as the Act Directs Oct 31st Copy 1 showing the scenes of our military operations during 1780. Original cloth backed. the present war; also the new erect state of Vermont New Netherlands, with a view of New Amsterdam (now US-1-4 1656 Not given 12" x 7" By A. Vander Donck. Copy 1 New York) Patroonships, manors and seigniories in New York US-1-5 [Rhode Island and Massachusetts] recognized the Order 1932 1" = 20 mi. 12"x8" By Max Mayer. Copy 1 of Colonial Lords of Manors United States, territories and insular possessions: Compiled from official surveys…Harry showing the extent of public surveys, Indian, military US-1-6 1899 Not given Not noted King, c.e. -- U.S. Dept of the Interior, Copy 1 and forest reservations, rail roads, canals and other General Land Office. -

New Madrid Seismic Zone: Overview of Earthquake Hazard and Magnitude Assessment Based on Fragility of Historic Structures

U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development Office of Policy Development and Research NEW MADRID SEISMIC ZONE: OVERVIEW OF EARTHQUAKE HAZARD AND MAGNITUDE ASSESSMENT BASED ON FRAGILITY OF HISTORIC STRUCTURES May 2003 PATH (Partnership for Advancing Technology in Housing) is a new private/public effort to develop, demonstrate, and gain widespread market acceptance for the “Next Generation” of American housing. Through the use of new or innovative technologies, the goal of PATH is to improve the quality, durability, environmental efficiency, and affordability of tomorrow’s homes. PATH is managed and supported by the Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD). In addition, all Federal Agencies that engage in housing research and technology development are PATH Partners, including the Departments of Energy and Commerce, as well as the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) and the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA). State and local governments and other participants from the public sector are also partners in PATH. Product manufacturers, home builders, insurance companies, and lenders represent private industry in the PATH Partnership. To learn more about PATH, please contact: 451 7th Street, SW Washington, DC 20410 202-708-5873 (fax) e-mail: [email protected] website: www.pathnet.org Visit PD&R's Web Site www.huduser.org to find this report and others sponsored by HUD's Office of Policy Development and Research (PD&R). Other services of HUD USER, PD&R's Research Information Service, include listservs; special interest, bimonthly publications (best practices, significant studies from other sources); access to public use databases; and hotline 1-800-245-2691 for help accessing the information you need. -

Liquefaction Susceptibility Mapping in Boston, Massachusetts

Liquefaction Susceptibility Mapping in Boston, Massachusetts CHARLES M. BRANKMAN1 William Lettis & Associates, Inc., 1777 Botelho Drive, Suite 262, Walnut Creek, CA 94596 LAURIE G. BAISE Department of Civil and Environmental Engineering, Tufts University, 113 Anderson Hall, Medford, MA 02155 Key Terms: Liquefaction, Seismic Hazards, Engineer- area, and it will assist in characterizing seismic ing Geology, Geotechnical, Surficial Geology hazards, mitigating risks, and providing information for urban planning and emergency response. ABSTRACT INTRODUCTION The Boston, Massachusetts, metropolitan area has Boston, Massachusetts, is located in a region of experienced several historic earthquakes of about moderate historic seismicity, where several historical magnitude 6.0. A compilation of surficial geologic events of about M6.0 have occurred (e.g., 1727, 1755). maps of the Boston, Massachusetts, metropolitan area The possibility therefore exists for the generation of and geotechnical analyses of Quaternary sedimentary earthquake-induced liquefaction of near-surface sedi- deposits using nearly 3,000 geotechnical borehole logs ments in the Boston area. In this paper, we present reveal varying levels of susceptibility of these units to results of a study to assess the liquefaction suscepti- earthquake-induced liquefaction, given the generally bility of natural sediments and areas of artificial fill in accepted design earthquake for the region (M6.0 with the Boston metropolitan area, with the aim of 0.12g Peak Ground Acceleration (PGA)). The majority characterizing liquefaction hazard and providing of the boreholes are located within the extensive information to local communities for improved downtown artificial fill units, but they also allow planning and mitigation strategies. The primary goal characterization of the natural deposits outside the of the study was to develop liquefaction susceptibility downtown area. -

5.4.5 Earthquake

SECTION 5.4.5: RISK ASSESSMENT – EARTHQUAKE 5.4.5 EARTHQUAKE This section provides a profile and vulnerability assessment for the earthquake hazard. HAZARD PROFILE This section provides profile information including description, extent, location, previous occurrences and losses and the probability of future occurrences. Description An earthquake is the sudden movement of the Earth’s surface caused by the release of stress accumulated within or along the edge of the Earth’s tectonic plates, a volcanic eruption, or by a manmade explosion (Federal Emergency Management Agency [FEMA], 2001; Shedlock and Pakiser, 1997). Most earthquakes occur at the boundaries where the Earth’s tectonic plates meet (faults); however, less than 10 percent of earthquakes occur within plate interiors. New York is in an area where plate interior-related earthquakes occur. As plates continue to move and plate boundaries change over geologic time, weakened boundary regions become part of the interiors of the plates. These zones of weakness within the continents can cause earthquakes in response to stresses that originate at the edges of the plate or in the deeper crust (Shedlock and Pakiser, 1997). The location of an earthquake is commonly described by its focal depth and the geographic position of its epicenter. The focal depth of an earthquake is the depth from the Earth’s surface to the region where an earthquake’s energy originates (the focus or hypocenter). The epicenter of an earthquake is the point on the Earth’s surface directly above the hypocenter (Shedlock and Pakiser, 1997). Earthquakes usually occur without warning and their effects can impact areas of great distance from the epicenter (FEMA, 2001). -

Response to Request for Additional Information, RAI No. 43, Vibratory Ground Motion

Nuclear Development 244 Chestnut Street, Salem, NJ 08079 0 PSEG Power LLC ND-2012-0039 July 19, 2012 U.S. Nuclear Regulatory Commission ATTN: Document Control Desk Washington, DC 20555-0001 Subject: PSEG Early Site Permit Application Docket No. 52-043 Response to Request for Additional Information, RAI No. 43, Vibratory Ground Motion References: 1) PSEG Power, LLC letter to USNRC, Application for Early Site Permit for the PSEG Site, dated May 25, 2010 2) RAI No. 43, SRP Section: 02.05.02 - Vibratory Ground Motion, dated December 12, 2011 (eRAI 6162) 3) PSEG Power, LLC Letter No. ND-2012-0002 to USNRC, Response to Request for Additional Information, RAI No. 43, Vibratory Ground Motion, dated January 10, 2012 4) PSEG Power, LLC Letter No. ND-2012-0006 to USNRC, Response to Request for Additional Information, RAI No. 43, Vibratory Ground Motion, dated January 25, 2012 5) PSEG Power, LLC Letter No. ND-2012-0009 to USNRC, Response to Request for Additional Information, RAI No. 43, Vibratory Ground Motion, dated February 9, 2012 6) PSEG Power, LLC Letter No. ND-2012-0018 to USNRC, Response to Request for Additional Information, RAI No. 43, Vibratory Ground Motion, dated March 15, 2012 U. S. Nuclear Regulatory 2 7/19/12 Commission The purpose of this letter is to respond to the request for additional information (RAI) identified in Reference 2 above. This RAI addresses Vibratory Ground Motion, as described in Subsection 2.5.2 of the Site Safety Analysis Report (SSAR), as submitted in Part 2 of the PSEG Site Early Site Permit Application, Revision 0. -

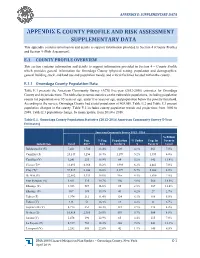

Appendix E – Supplementary Data

APPENDIX E: SUPPLEMENTARY DATA COUNTY PROFILE AND RISK ASSESSMENT SUPPLEMENTARY DATA This appendix contains information and details to support information provided in Section 4 (County Profile) and Section 5 (Risk Assessment). E.1 COUNTY PROFILE OVERVIEW This section contains information and details to support information provided in Section 4 – County Profile which provides general information for Onondaga County (physical setting, population and demographics, general building stock, and land use and population trends) and critical facilities located within the county. E.1.1 Onondaga County Population Data Table E.1 presents the American Community Survey (ACS) five-year (2012-2016) estimates for Onondaga County and its jurisdictions. The table also presents statistics on the vulnerable populations, including population counts for population over 65 years of age, under five years of age, and population below the poverty threshold. According to the survey, Onondaga County had a total population of 468,050. Table E.2 and Table E.3 present population changes in the county. Table E.2 includes county population trends and projections from 1800 to 2040. Table E.3 population change, by municipality, from 2010 to 2016. Table E.1. Onondaga County Population Statistics (2012-2016 American Community Survey 5-Year Estimates) American Community Survey 2012 - 2016 % Below Pop. % Pop. Population % Under Pop. In Poverty Jurisdiction Total 65+* 65+ Under 5 5 Poverty Level Baldwinsville (V) 7,461 1,746 23.4% 303 4.1% 563 7.5% Camillus (T) 23,149 4,256 -

Unistar Nuclear Services, LLC

FSAR: Section 2.5 Geology, Seismology, and Geotechnical Engineering 2.5 GEOLOGY, SEISMOLOGY, AND GEOTECHNICAL ENGINEERING {This section presents information on the geological, seismological, and geotechnical engineering properties of the Nine Mile Point 3 Nuclear Power Plant (NMP3NPP) site. Section 2.5.1 describes basic geological and seismologic data, focusing on those data developed since the publication of the Final Safety Analysis Report (FSAR) for licensing Nine Mile Point (NMP) Unit 1 and Unit 2. Section 2.5.2 describes the vibratory ground motion at the site, including an updated seismicity catalog, description of seismic sources, and development of the Safe Shutdown Earthquake and Operating Basis Earthquake ground motions. Section 2.5.3 describes the potential for surface faulting in the site area, and Section 2.5.4 and Section 2.5.5 describe the stability of surface materials at the site. Appendix D of Regulatory Guide 1.165, “Geological, Seismological and Geophysical Investigations to Characterize Seismic Sources,” (NRC, 1997) provides guidance for the recommended level of investigation at different distances from a proposed site for a nuclear facility. The site region is that area within 200 mi (322 km) of the site location The site vicinity is that area within 25 mi (40 km) of the site location The site area is that area within 5 mi (8 km) of the site location The site is that area within 0.6 mi (1 km) of the site location These terms, site region, site vicinity, site area, and site, are used in Section 2.5.1 through Section 2.5.3 to describe these specific areas of investigation. -

United States Department of the Interior Geological Survey a Review of Earthquake Research Applications in the National Earthqua

UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR GEOLOGICAL SURVEY A REVIEW OF EARTHQUAKE RESEARCH APPLICATIONS IN THE NATIONAL EARTHQUAKE HAZARDS REDUCTION PROGRAM: 1977-1987 PROCEEDINGS OF CONFERENCE XLI SAN DIEGO, CALIFORNIA - JUNE 23-25, 1987 DENVER, COLORADO - SEPTEMBER 9-11, 1987 KNOXV1LLE, TENNESSEE - OCTOBER 20-22, 1987 SPONSORED BY THE U,S, GEOLOGICAL SURVEY, THE NATIONAL SCIENCE FOUNDATION, THE FEDERAL EMERGENCY MANAGEMENT AGENCY, AND THE NATJflMfiLJUREAU OF STANDARDS OPEN-FILE REPORT 88-15-A This report is preliminary and has not been edited or reviewed for conformity with U.S. Geological Survey publication standards and stratigraphic nomenclature. The views and conclusions contained in this document are those of the authors and should not be interpreted as necessarily representing the official policies, either expressed or implied, of the United States Government. Any use of trade names and trademarks in this publication is for descriptive purposes only and does not constitute endorsement by the U.S. Geological Survey. Reston, Virginia 1988 UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR GEOLOGICAL SURVEY A REVIEW OF EARTHQUAKE RESEARCH APPLICATIONS IN THE NATIONAL EARTHQUAKE HAZARDS REDUCTION PROGRAM: 1977-1987 PROCEEDINGS OF CONFERENCE XLI SAN DIEGO, CALIFORNIA - JUNE 23-25. 1987 DENVER. COLORADO - SEPTEMBER 9-11. 1987 KNOXVILLE, TENNESSEE - OCTOBER 20-22. 1987 SPONSORED BY THE U.S. GEOLOGICAL SURVEY, THE NATIONAL SCIENCE FOUNDATION. THE FEDERAL EMERGENCY MANAGEMENT AGENCY. AND THE NATIONAL BUREAU OF STANDARDS OPEN-FILE REPORT 88-13-A This report is preliminary and has not been edited or reviewed for conformity with U.S. Geological Survey publication standards and stratigraphic nomenclature. The views and conclusions contained in this document are those of the authors and should not be interpreted as necessarily representing the official policies, either expressed or implied, of the United States Government.