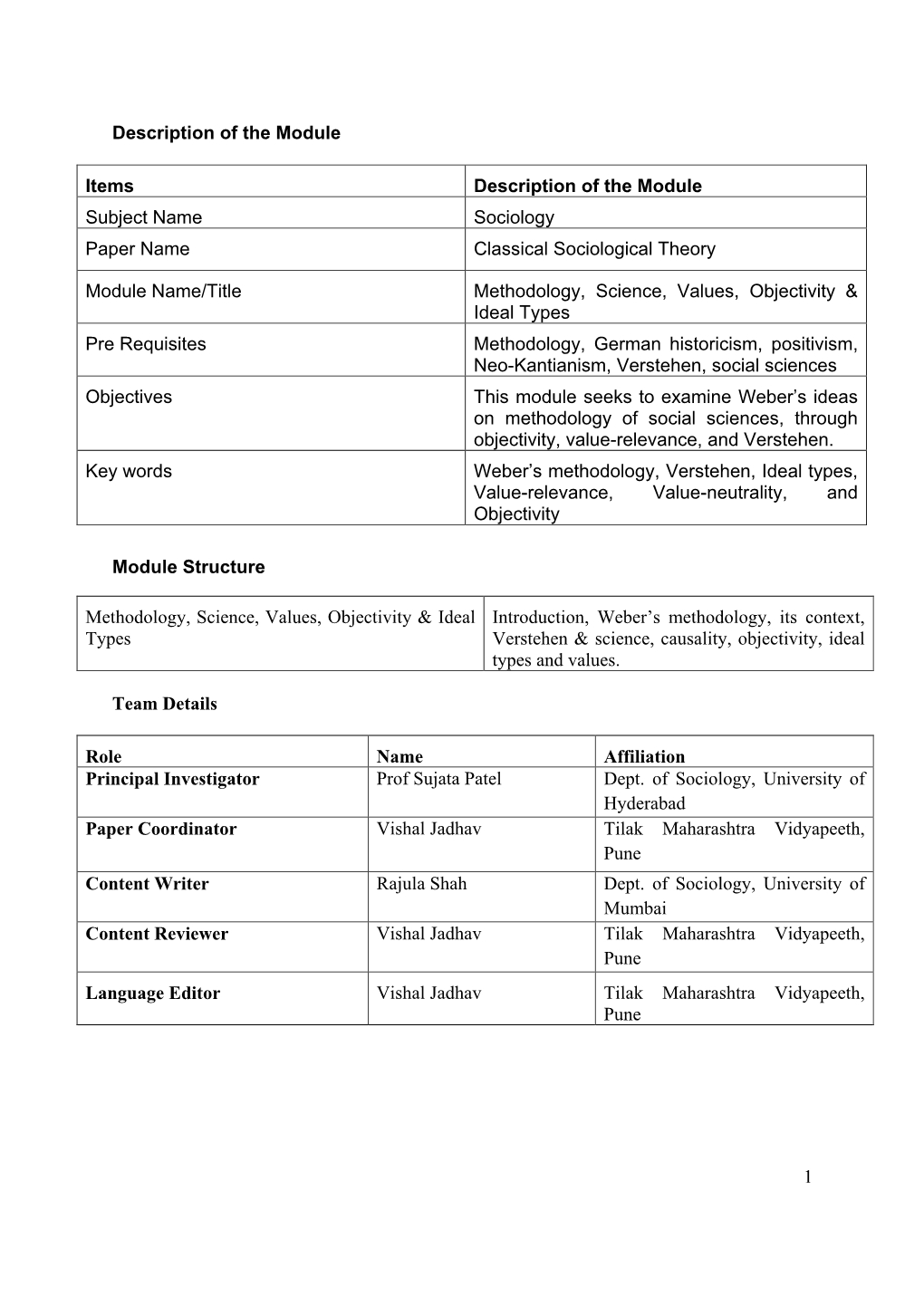

1 Description of the Module Items Description of the Module Subject

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Charismatic Leadership and Democratization : a Weberian Perspective 1

CHARISMATIC LEADERSHIP AND DEMOCRATIZATION : A WEBERIAN PERSPECTIVE 1 Michael Bernhar d Associate Professor of Political Science The Pennsylvania State University SUMMARY 2 In at least three cases of democratization in Eastern and Central Europe (ECE), charismati c leaders have played an important role in overthrowing the old regime and in shaping the pattern of new institutions . In addition to Lech Wa łęsa in Poland, Vaclav Havel of the Czech (and formerly Slovak) Republic, and Boris Yeltsin of Russia, can be classified as charismatic leaders with littl e controversy . While there are other charismatic leaders in the region, their commitments t o democracy are quite shaky, and thus they fall outside the scope of this paper . The greatest contribution to our understanding of charisma as a social force has been the wor k of Max Weber. His sociological writings on charisma serve as the point of departure for this paper . After surveying Weber's analysis of charisma, this study turns to what his writings tell us about th e relationship between charisma and democracy. It then addresses the question of the impact tha t democratization has on charismatic leadership and use this to interpret the political fortunes of Lec h Wałęsa, Vaclav Havel, and Boris Yeltsin . It concludes with a discussion of the role of charisma i n both democracy and dictatorship in the contemporary era . Despite their pivotal role in the demise of the communist regimes in their countries and thei r leadership during key phases of the democratization process, none of the three leaders have bee n fully successful in translating their visions for their respective countries into reality . -

Alfred Weber, Theory of the Location of Industries, 1909

UC Santa Barbara CSISS Classics Title Alfred Weber, Theory of the Location of Industries, 1909. CSISS Classics Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/1k3927t6 Author Fearon, David Publication Date 2002 eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California CSISS Classics - Alfred Weber: Theory of the Location of Industries, 1909 Alfred Weber: Theory of the Location of Industries, 1909 By David Fearon Background Alfred Weber (1868–1958), like his older brother Max Weber, started his academic career in Germany as an economist, then became a sociologist. While schooled at a time when European economics was emphasizing historical analysis, Weber was among those reintroducing theory and causal models to the field. He is best remembered, particularly in economics, regional science and operations research, for early models of industrial location (discussed below). When his work turned to sociology, however, Weber maintained a commitment to the "philosophy of history" traditions, developing theories for analyzing social change in Western civilization as a confluence of civilization (intellectual and technological), social processes (organizations) and culture (art, religion, and philosophy). He also published empirical and historical analyses of the growth and geographical distribution of cities and capitalism. Weber remained in Nazi Germany during the war, but was a leader in intellectual resistance. After the war his writings and teaching was influential both in and out of academic circles in promoting a philosophical and political recovery for the German people. Innovation With the publication of Über den Standort der Industrie (Theory of the Location of Industries) in 1909, Alfred Weber put forth the first developed general theory of industrial location [references here are to the 1929 translation of the 1909 book by Carl Friedrich]. -

Weber's Ideal Types and Idealization

Weber’s ideal types and idealization Juraj Halas Max Weber’s “ideal types” (its) have long drawn the attention of philosophers of science. Proponents of the Poznan School have formulated at least two different methodological reconstructions of Weber’s conception. One, by Izabella Nowakowa, views its as extreme elements of classifications and argues that the procedure employed in constructing its is but a special case of the method of idealization. Another, by Leszek Nowak, explicates ideal-typical statements as analytic statements which perform explanatory or heuristic functions. In this paper, I assess these reconstructions and confront them with Weber’s original writings. I show that both are inadequate and propose a new one, based on a revised conception of abstraction and idealization. I show that the heuristic function of its, as discussed by Weber, consists in their role in formulating contrastive explanations. This work was supported by the Slovak Research and Development Agency under the contract No. APVV-0149-12. Introduction Max Weber’s writings on “ideal types” (its) have been an important influence in the debates on the philosophy and methodology of social sciences and the hu- manities. In the context of the Poznan School of philosophy of science, at least two contributions to the reconstruction of its have emerged. Unlike Hempel, both emphasize the role of idealization. The historically prior approach is due to Leszek Nowak and was first formulated in English in his (1980). The second approach was presented by Izabella Nowakowa in (2007). This paper critically examines both contributions. In the first part, I briefly restate the accounts weber’s ideal types and idealization 2 and argue that neither of them adequately captures the intent of Weber’s con- ception. -

Current Trends in Theories of Religious Studies: a Clue to Proliferation of Religions Worldwide

Global Journal of Arts Humanities and Social Sciences Vol.2,No.7, pp. 27-46, September 2014 Published by European Centre for Research Training and Development UK (www.eajournals.org) CURRENT TRENDS IN THEORIES OF RELIGIOUS STUDIES: A CLUE TO PROLIFERATION OF RELIGIONS WORLDWIDE Nathaniel Aminorishe Ukuekpeyetan--Agbikimi -- Ph. D ABSTRACT: The thrust of this paper is to unveil the current trends in the theories of religious studies since 1970 till date and to show how they have led to proliferation of religious groups worldwide. The presupposition here is that there has been existing theories in comparison to happenings in contemporary times. The existing theories include: (1) theories of religion propounded for the primitive period, which have a leaning towards distinguishing between the sacred and the profane; and (2) those for the Middle Ages that orchestrated polemic and apologetic writings as a result of the renaissance. Thus, the need for a comparative treatment of religion became clear, and this prepared the way for more modern developments that paved way for Pentecostalism, Spiritism sects, etc. The sacred defines the world of reality, which is the basis for all meaningful forms and behaviours in the society. The profane is the opposite of the sacred. By theories of religion one means a body of explanations, rules, ideas, principles, and techniques that are systematically arranged to guide and guard religious practices for comprehension. These theories are categorized into substantive theories, focusing on what the value of religion for its adherents is, and functional or reductionist theories, focusing on what it does. The method adopted to obtain the goal of this study is through library research. -

"Capitalism" in Recent Ge&Man Lite&Atu&E

!"#$%&#'%()!*%+*,-.-+&*/-0)#+*1%&-0#&20-3*45)6#0&*#+7*8-6-0*9"5+.'27-7: ;2&<509(:3*=#'.5&&*>#0(5+( 4520.-3*?520+#'*5@*>5'%&%.#'*A.5+5)BC*D5'E*FGC*H5E*I*9J-6EC*IKLK:C*$$E*FIMNI >26'%(<-7*6B3*The University of Chicago Press 4'-*O,13*http://www.jstor.org/stable/1822319 . ;..-((-73*IPQRKQLRII*IL3NI Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at . http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. The University of Chicago Press is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Journal of Political Economy. http://www.jstor.org "CAPITALISM" IN RECENT GERMAN LITERATURE: SOMBART AND WEBER-Concluded i M [AX WEBER has none of Sombart'sconcentration of attention upon a single line of development. His re- searches extend over the whole of human history. He investigates the classic world, China, India, ancient Judea, and others. But it always remains his purpose to throw light upon the problems of modem society, and especially upon modern capitalism.2"Thus in spite of methodologicaldifferences between the two scholars, the one working genetically, the other by the comparativemethod, with the aid of "ideal types," the final ob- ject in View is the same, to understand the peculiarities of our modern economic and social situation. -

The Example of Max Weber

Advances in Applied Sociology, 2020, 10, 1-10 https://www.scirp.org/journal/aasoci ISSN Online: 2165-4336 ISSN Print: 2165-4328 The Importance of Models in Sociology: The Example of Max Weber Albertina Oliverio Department of Law and Social Sciences, Università Degli Studi G. D’Annunzio—Chieti-Pescara, Chieti, Italy How to cite this paper: Oliverio, A. (2020). Abstract The Importance of Models in Sociology: The Example of Max Weber. Advances in Sociological research method may be resumed by three concepts of Karl R. Applied Sociology, 10, 1-10. Popper, “problems-theories-critics”. Within this field, the role of theoretical https://doi.org/10.4236/aasoci.2020.101001 models is central. In particular, the concept of model is comparable to the one Received: December 7, 2019 of ideal type conceived by Max Weber. As a matter of fact, Weberian ideal type Accepted: December 23, 2019 is still one of the most popular methodological instruments in social sciences. Published: December 26, 2019 Conceived as a non-normative form of conceptualization finalized to simplify and reduce external social world complexity, ideal type allows the organiza- Copyright © 2020 by author(s) and Scientific Research Publishing Inc. tion of an increasing knowledge acquaintance. It is shown that as a significant This work is licensed under the Creative character of understanding sociology, ideal type is founded on an individual- Commons Attribution International istic and nomological epistemological substrate. Conceived in these terms, it License (CC BY 4.0). is argued that ideal type is therefore the expression of a unique method of ex- http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ planation which can be traced in some examples showing how models con- Open Access struction is one of sociology’s most used instruments. -

Richard Swedberg

[MWS (2006 Bhft I) 121-134] ISSN 1470-8078 Verstehende Wirtschaftssoziologie? On the Relationship between Max Weber’s ‘Basic Sociological Concepts’ and His Economic Sociology Richard Swedberg This paper will explore the extent to which we are justified in cast- ing Weber’s economic sociology as an interpretive economic sociol- ogy, or a verstehende Wirtschaftssoziologie.1 The term is nowhere to be found in Weber’s work; but draws a link to Werner Sombart’s phrase verstehende Nationalökonomie (Sombart 1930). The main thrust of Sombart’s argument about an interpretive economics was how- ever that economics belonged to the cultural sciences and should be replaced by sociology.2 The main emphasis here, by contrast, is to examine whether there is any systematic connection between Weber’s chapter on ‘Basic Sociological Concepts’ in Economy and Society and his economic sociology. On the Possible Relevance of Ch. 1 (‘Grundbegriffe’) to Weber’s Economic Sociology Weber’s project of an interpretive sociology (verstehende Soziologie) is famously discussed and presented in the first chapter of Economy and Society, ‘Basic Sociological Concepts’. There is of course an early ver- sion of this text, published in 1913 under the title ‘Some Categories of 1. The author warmly thanks Keith Tribe for shortening a lengthy argument into its current concise form. 2. According to Ludwig Lachmann, ‘During the 1920s, when there was no single dominant school of economic theory in the world, and streams of thought flowing from diverse sources (such as Austrian, Marshallian and Paretian) each had their own sphere of influence, “interpretive” voices (mostly of Weberian origin) were still audi- ble on occasions. -

IDEAL TYPES Ideal Types

UNIT 14 IDEAL TYPES Ideal Types Structure 14.0 Objectives 14.1 Introduction 14.2 Ideal Types: Meanings, Construction and Characteristics 14.2.0 Meaning 14.2.1 Construction 14.2.2 Characteristics 14.3 Purpose and Use of Ideal Types 14.4 Ideal Types in Weber’s Work 14.4.0 Ideal Types of Historical Particulars 14.4.1 Abstract Elements of Social Reality 14.4.2 Reconstruction of a Particular Kind of Behaviour 14.5 Let Us Sum Up 14.6 Keywords 14.7 Further Reading 14.8 Specimen Answers To Check Your Progress 14.0 OBJECTIVES After reading this unit you should be able to z discuss the meaning and characteristics of ideal types z describe the purpose and use of ideal types in social sciences z narrate Max Weber’s use of ideal type in his major works. 14.1 INTRODUCTION This is the first unit of the block on Max Weber. It deals with the concept of ideal type as part of Max Weber’s concern with methodology of social sciences. This unit gives a perspective and a background to analyse the major theoretical formulations of Max Weber. In this unit first we clarify the general meaning of ideal type and explain the sociological concept and characteristics of ideal-type as reflected in the writing of Max Weber. Here we also answer two questions as to how and why of social scientists’ construction of ideal type in their researches. Weber used ideal type in three distinctive ways. We explain these three ways of use of ideal type in Weber’s work in terms of (a) ideal types of historical particulars, (b) ideal types of abstract elements of social reality and (c) ideal types relating to the reconstruction of a particular kind of behaviour. -

Christopher Adair-Toteff

Adair-Toteff A Max Weber 'Wish List' A Max Weber ‘Wish List’ Christopher Adair-Toteff It has been one hundred years since Max Weber died and we are still wondering how much do we really know him. There is no doubt that thousands of books and articles have been written about him and he has been the topic of hundreds of conference panels. But I wonder how much we understand his thinking. I was trained as a philosopher so I tend to subscribe to Socrates’ claim that the beginning of wisdom is realizing what one does not know. But I have been considered to be a Weber expert so there is some tension between what people think I know and what I have been trained to think. And, what I think is that there are many aspects of Weber’s thinking that I don’t seem to understand. Some of this is because my own efforts have not been focused on a specific area and some of it is because of others not having a particular interest in those areas. In what follows, I set out six areas that I am convinced need serious investigation. This list is entirely subjective and it is not exhaustive, but it may propel some scholars to focus on a specific area and it might prompt others to formulate their own Weber ‘wish list.’ There is a seventh wish, but that applies mostly to others and I will give my reasons for that later. Taken all together, this is my Weber ‘Wish List.’ Max Weber has long been regarded not only as a major sociologist, but he has been revered as one of the founders of sociology. -

The Pure Theory As Ideal Type: Defending Kelsen on the Basis of Weberian Methodology

The Pure Theory as Ideal Type: Defending Kelsen on the Basis of Weberian Methodology Dhananjai Shivakumar Although Hans Kelsen is widely regarded as the most influential legal positivist of his generation,' his "pure theory" of law has often struck theorists in the Anglo-American legal tradition as an exercise in theoretical system- building out of touch with legal reality.2 This is due in large part to Kelsen's Kantian (or neo-Kantian) methodology. This methodology, by claiming to identify and analyze the necessary conditions of legal cognition, appears to distance the concerns of the legal scholar from the problems facing both practicing lawyers, on the one hand, and social theorists and reformers, on the other. This Note seeks to reduce the strangeness of Kelsenian jurisprudence3 1. See, e.g., H.L.A. Hart, Kelsen Visited, 10 UCLA L. REV. 709,728 (1963) (describing Kelsen as "the most stimulating writer on analytical jurisprudence of our day"); Graham Hughes, Validity and the Basic Norm, 59 CAL. L. REV. 695, 695 (1971) ("As we move toward the last quarter of the 20th century, there can no longer be any doubt that the formative jurist of our time is Hans Kelsen."). 2. See, e.g., CARLETON K. ALLEN, LAW IN THE MAKING 51 (5th ed. 1951) ("[The 'pure' essence distilled by the [Kelsenian] jurist is a colourless, tasteless, and unnutritious fluid which soon evaporates."); KARL N. LLEWELLYN, JURISPRUDENCE: REALISM IN THEORY AND PRACrICE 356 n.5 (1962) (describing Kelsen's pure theory of law as "utterly sterile"). The objection that Kelsen's legal theory is too detached from politics and purposeful human activity to contribute to our understanding of the nature of law was not raised exclusively by English and American jurisprudes. -

IDEAL TYPES and the PROBLEM of REIFICATION Fred Eidlin

IDEAL TYPES AND THE PROBLEM OF REIFICATION Fred Eidlin Department of Political Studies University of Guelph Guelph, Ontario, Canada N1G 2W1 Office phone: (519) 824-4120 ext. 3469 Home phone: (519) 821-6892 fax: (519) 837-9561 e-mail: [email protected] IDEAL TYPES AND THE PROBLEM OF REIFICATION Abstract Social scientists are usually aware that ideal types are merely constructs that pick out, indeed exaggerate preselected aspects of social reality. Nevertheless, there remains a tendency to treat them as if they referred to entities actually existing in the social world. This paper attempts to demonstrate how the very attempt to avoid reification by denying existence to social things encourages a tendency to reify ideal types and other constructs which social science imposes on social reality. It argues that without a realistic ontology of the social, it is difficult to envision how social reality might "kick" at the constructs social science seeks to impose upon them and render them problematic. The constructs of social science select out of an undifferentiated universe of facts only those which they, themselves, have predetermined to be germane. Once so selected, the facts become linguistically and psychologically fused with the constructs that selected them. All science attempts to simplify and typify the reality it seeks to represent. However, it is the notion of a reality independent of the constructs science attempts to impose on it that compels scientists to abandon or modify these constructs as inadequate representations. Finally, the paper explores various concrete sources of orderliness in social reality that can serve as objective constraints on the hypotheses social science seeks to impose on them. -

Honours) in Sociology (Baso

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT This course material is designed and developed by Indira Gandhi National Open University (IGNOU), New Delhi and e-PG Pathshala. BACHELOR OF ARTS (HONOURS) IN SOCIOLOGY (BASO) BSO-5 Classical Sociological Thinkers BLOCK – 4 MAX WEBER UNIT-1 SOCIAL ACTION UNIT-2 PROTESTANT ETHIC AND THE SPIRIT OF CAPITALISM UNIT-3 IDEAL TYPE UNIT-4 AUTHORITY AND BUREAUCRACY BLOCK 4 : MAX WEBER This Block deals with another German social theorist, Max Weber. The Block is divided into four units. Unit 1 introduces the learners to the sociology of Weber. The basic sociological terms and concepts of Weber are elaborated in this Unit which also covers the theory of social action and rationality. An important contribution of Weber i.e. The Protestant Ethic and the Spirit of Capitalism is discussed in the Unit 2. Unit 3 discusses the methodology of Weber i.e. Ideal types. One of his major contributions in the field of religion and social change is discussed in Unit 4 i.e. Weber’s views on the link between religion and the rise of capitalism in the West. UNIT 1 : SOCIAL ACTION STRUCTURE 1.1 Introduction 1.2 Learning Objectives 1.3 Max Weber (1864-1920) 1.3.1 Biographical Sketch 1.3.2 The Central Ideas 1.4 Subjective Understanding of Social Action 1.4.1 Social Action 1.4.2 Subjective Meaning of Social Action 1.5 Natural Science and Social Science 1.6 Sociological Methodology 1.7 Critical Assessment of Weber’s Contributions 1.8 Let Us Sum Up 1.9 Glossary 1.10 Check Your Progress: The Answer Keys 1.11 References 1.1 INTRODUCTION A contemporary of Durkheim, Max Weber (1864-1920) was concerned with the development of that dimension which he thought most essential and promising for the furtherance of the science of Sociology.